Geological Survey of Alabama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Mississippi Bird EA

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Managing Damage and Threats of Damage Caused by Birds in the State of Mississippi Prepared by United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services In Cooperation with: The Tennessee Valley Authority January 2020 i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Wildlife is an important public resource that can provide economic, recreational, emotional, and esthetic benefits to many people. However, wildlife can cause damage to agricultural resources, natural resources, property, and threaten human safety. When people experience damage caused by wildlife or when wildlife threatens to cause damage, people may seek assistance from other entities. The United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services (WS) program is the lead federal agency responsible for managing conflicts between people and wildlife. Therefore, people experiencing damage or threats of damage associated with wildlife could seek assistance from WS. In Mississippi, WS has and continues to receive requests for assistance to reduce and prevent damage associated with several bird species. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to incorporate environmental planning into federal agency actions and decision-making processes. Therefore, if WS provided assistance by conducting activities to manage damage caused by bird species, those activities would be a federal action requiring compliance with the NEPA. The NEPA requires federal agencies to have available -

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN)

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

REPORT FOR: Preliminary Analysis for Identification, Distribution, And

REPORT FOR: Preliminary Analysis for Identification, Distribution, and Conservation Status of Species of Fusconaia and Pleurobema in Arkansas Principle Investigators: Alan D. Christian Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, P.O. Box 599, State University, Arkansas 72467; [email protected]; Phone: (870)972-3082; Fax: (870)972-2638 John L. Harris Department of Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University, P.O. Box 599, State University, Arkansas 72467 Jeanne Serb Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, 251 Bessey Hall, Ames, Iowa 50011 Graduate Research Assistant: David M. Hayes, Department of Environmental Science, P.O. Box 847, State University, Arkansas 72467: [email protected] Kentaro Inoue, Department of Environmental Science, P.O. Box 847, State University, Arkansas 72467: [email protected] Submitted to: William R. Posey Malacologist and Commercial Fisheries Biologist, AGFC P.O. Box 6740 Perrytown, Arkansas 71801 April 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY There are currently 13 species of Fusconaia and 32 species of Pleurobema recognized in the United States and Canada. Twelve species of Pleurobema and two species of Fusconaia are listed as Threatened or Endangered. There are 75 recognized species of Unionidae in Arkansas; however this number may be much higher due to the presence of cryptic species, many which may reside within the Fusconaia /Pleurobema complex. Currently, three species of Fusconaia and three species of Pleurobema are recognized from Arkansas. The true conservation status of species within these genera cannot be determined until the taxonomic identity of populations is confirmed. The purpose of this study was to begin preliminary analysis of the species composition of Fusconaia and Pleurobema in Arkansas and to determine the phylogeographic relationships within these genera through mitochondrial DNA sequencing and conchological analysis. -

Host Fishes and Reproductive Biolo K Y of 6 Freshwater Mussel Species From

J. N. Am. Benthol. Sm., 1997, 16(3):57&585 0 1997 by The North Amerxan Benthologxal ‘Society Host fishes and reproductive biolo y of 6 freshwater mussel species from the MobiK e Basin, USA W ENDELL R. HAAG AND M ELVIN L. WARREN, JR US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Forest Hydrology Laboratory, 1000 Front Street, Oxford, Mississippi 38655 USA Abstract. Host fishes were identified for 6 species of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from the Black Warrior River drainage, Mobile Basin, USA: Stropkitus subwxus, Pleurohemafurvum, Ptyckobran- thus greeni, Lampsilis yrrovnlis, Medionidus arutissimus, and Villosa nebulosn. Hosts were determined as those that produced juvenile mussels from glochidial infestations in the laboratory. The following mussel-fish-host relationships were established: Stropkitus subwxus with 10 species including Cy- prinidae, Catostomidae, Fundulidae, Centrarchidae, and Percidae; Pleurobemafurvum with Campostoma oligolepis, Cyprirlella callistia, C. uenusta, Srmotilus atromaculatus, and Fund&s olimceus; Ptyckobrunckus greeni with Etlleostoma brllator, E. doughs-i, Per&a nigroj&iata, and Percina sp. cf. caprodes; Lampsilis pen&is with Micropterus coosae, M. puuctulatus, and M. salmoides; Medionidus acutissimus with Fundulus olivuceus, Etkeostoma doughsi, E. wkipplei, Percina nigrqfusciata, and Percinn sp. cf. caprodes; and Villosa wbulosa with LqOnlis megul$is, Micropterus coosae, M. punctulutus, and M. sulmoides. Funduhs olhuceus served as host for 3 species and carried glochidia for long periods for 2 other species, suggesting that topminnows may serve as hosts for a wide variety of otherwise host-specialist mussel species. Host relationships for the species tested are similar to congeners. Methods of glochidial release, putative methods of host-fish attraction, and gravid periods are described for the 6 species. -

Alasmidonta Varicosa) Version 1.1.1

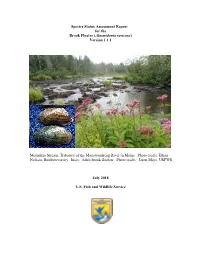

Species Status Assessment Report for the Brook Floater (Alasmidonta varicosa) Version 1.1.1 Molunkus Stream, Tributary of the Mattawamkeag River in Maine. Photo credit: Ethan Nedeau, Biodrawversity. Inset: Adult brook floaters. Photo credit: Jason Mays, USFWS. July 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service This document was prepared by Sandra Doran of the New York Ecological Services Field Office with assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Brook Floater Species Status Assessment (SSA) Team. The team members include Colleen Fahey, Project Manager (Species Assessment Team (SAT), Headquarters (HQ) and Rebecca Migala, Assistant Project Manager, (Region 1, Regional Office), Krishna Gifford (Region 5, Regional Office), Susan (Amanda) Bossie (Region 5 Solicitor's Office, Julie Devers (Region 5, Maryland Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Jason Mays (Region 4, Asheville Field Office), Rachel Mair (Region 5, Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery), Robert Anderson and Brian Scofield (Region 5, Pennsylvania Field Office), Morgan Wolf (Region 4, Charleston, SC), Lindsay Stevenson (Region 5, Regional Office), Nicole Rankin (Region 4, Regional Office) and Sarah McRae (Region 4, Raleigh, NC Field Office). We also received assistance from David Smith of the U.S. Geological Survey, who served as our SSA Coach. Finally, we greatly appreciate our partners from Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada, the Brook Floater Working Group, and others working on brook floater conservation. Version 1.0 (June 2018) of this report was available for selected peer and partner review and comment. Version 1.1 incorporated comments received on V 1.0 and was used for the Recommendation Team meeting. This final version, (1.1.1), incorporates additional comments in addition to other minor editorial changes including clarifications. -

Rare Animals Tracking List

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

Changes in the Freshwater Mussel Assemblage in the East Fork Tombigbee River, Mississippi: 1988–2011

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2013 Department of Biology CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD August 2013 APPROVED BY: Dr. Michael M. Gangloff Chairperson, Thesis Committee Dr. Robert P. Creed Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Mike D. Madritch Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Sue L. Edwards Chairperson, Department of Biology Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Byron Hamstead 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 Byron Hamstead B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Michael Gangloff The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway is among the largest and most expensive environmental engineering projects of the 20th century. The waterway accommodates barge navigation between the Tennessee River drainage and Mobile River Basin through a series of locks, dams, canals, and dredged and diverted streams. These alterations have destroyed much riverine habitat and fragmented remaining aquatic habitats resulting in isolated freshwater mussel populations in patches of streams like the East Fork Tombigbee River, where 42 species were historically known. The first post-waterway mussel surveys in 1987 and 1988 reported 31 taxa (including 2 federally-listed species). -

Freshwater Mussel Survey Protocol for the Southeastern Atlantic Slope and Northeastern Gulf Drainages in Florida and Georgia

FRESHWATER MUSSEL SURVEY PROTOCOL FOR THE SOUTHEASTERN ATLANTIC SLOPE AND NORTHEASTERN GULF DRAINAGES IN FLORIDA AND GEORGIA United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services and Fisheries Resources Offices Georgia Department of Transportation, Office of Environment and Location April 2008 Stacey Carlson, Alice Lawrence, Holly Blalock-Herod, Katie McCafferty, and Sandy Abbott ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For field assistance, we would like to thank Bill Birkhead (Columbus State University), Steve Butler (Auburn University), Tom Dickenson (The Catena Group), Ben Dickerson (FWS), Beau Dudley (FWS), Will Duncan (FWS), Matt Elliott (GDNR), Tracy Feltman (GDNR), Mike Gangloff (Auburn University), Robin Goodloe (FWS), Emily Hartfield (Auburn University), Will Heath, Debbie Henry (NRCS), Jeff Herod (FWS), Chris Hughes (Ecological Solutions), Mark Hughes (International Paper), Kelly Huizenga (FWS), Joy Jackson (FDEP), Trent Jett (Student Conservation Association), Stuart McGregor (Geological Survey of Alabama), Beau Marshall (URSCorp), Jason Meador (UGA), Jonathon Miller (Troy State University), Trina Morris (GDNR), Ana Papagni (Ecological Solutions), Megan Pilarczyk (Troy State University), Eric Prowell (FWS), Jon Ray (FDEP), Jimmy Rickard (FWS), Craig Robbins (GDNR), Tim Savidge (The Catena Group), Doug Shelton (Alabama Malacological Research Center), George Stanton (Columbus State University), Mike Stewart (Troy State University), Carson Stringfellow (Columbus State University), Teresa Thom (FWS), Warren Wagner (Environmental Services), Deb -

Changes in the Freshwater Mussel Assemblage in the East Fork Tombigbee River, Mississippi: 1988–2011

CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2013 Department of Biology CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 A Thesis by BYRON A. HAMSTEAD August 2013 APPROVED BY: Dr. Michael M. Gangloff Chairperson, Thesis Committee Dr. Robert P. Creed Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Mike D. Madritch Member, Thesis Committee Dr. Sue L. Edwards Chairperson, Department of Biology Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Byron Hamstead 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract CHANGES IN THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL ASSEMBLAGE IN THE EAST FORK TOMBIGBEE RIVER, MISSISSIPPI: 1988–2011 Byron Hamstead B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Michael Gangloff The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway is among the largest and most expensive environmental engineering projects of the 20th century. The waterway accommodates barge navigation between the Tennessee River drainage and Mobile River Basin through a series of locks, dams, canals, and dredged and diverted streams. These alterations have destroyed much riverine habitat and fragmented remaining aquatic habitats resulting in isolated freshwater mussel populations in patches of streams like the East Fork Tombigbee River, where 42 species were historically known. The first post-waterway mussel surveys in 1987 and 1988 reported 31 taxa (including 2 federally-listed species). I sampled 70 sites in 2010 and 2011 using both quadrats and timed searches and found 29 species to be extant. -

In Mississippi National Forests

SUMMARY Little is known about the distribution of freshwater mussels in Mississippi national forests. Review of the scant available infor- mation revealed that the national forests harbor a diverse mus- sel fauna of possibly 46 or more species (including confirmed, probable, and potential occurrences). Occurrence of 33 species is confirmed. Because of the geographic, physiographic, and drain- age basin diversity of Mississippi national forests, there is con- siderable variation in mussel communities among the national forests. Three distinct fauna1 groups are represented in Missis- sippi national forests, each with a characteristic assemblage of species. One species of potential occurrence is a federally endan- gered species, 1 species of confirmed occurrence is a candidate for listing, and 11 species of confirmed or probable occurrence are considered of special concern by the American Fisheries Society (Williams and others 1993). None of the national forests have been surveyed adequately, and specific population data are almost com- pletely lacking. This review of existing information represents the first of a three-phase program needed to comprehensively evalu- ate the mussel resources of Mississippi national forests. Phase two involves an exhaustive, qualitative field survey of Mississippi national forests to document precise distribution of species and location of important communities. Phase three consists of a quan- titative study of important communities in order to assess repro- ductive characteristics and viability and to establish baseline density estimates for monitoring of future population trends. Cover: left, Lampsilis cardium; top right, Utterbackia imbecillis; bottom right, Potamilus ohiensis. Current Distributional Information on Freshwater Mussels (family Unionidae) in Mississippi National Forests Wendell R. -

Long-Term Monitoring Reveals Differential Responses of Mussel and Host Fish Communities in a Biodiversity Hotspot

diversity Article Long-Term Monitoring Reveals Differential Responses of Mussel and Host Fish Communities in a Biodiversity Hotspot Irene Sanchez Gonzalez * , Garrett W. Hopper , Jamie Bucholz and Carla L. Atkinson Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, USA; [email protected] (G.W.H.); [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (C.L.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Biodiversity hotspots can serve as protected areas that aid in species conservation. Long- term monitoring of multiple taxonomic groups within biodiversity hotspots can offer insight into factors influencing their dynamics. Mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) and fish are highly diverse and imperiled groups of organisms with contrasting life histories that should influence their response to ecological factors associated with local and global change. Here we use historical and contemporary fish and mussel survey data to assess fish and mussel community changes over a 33 year period (1986–2019) and relationships between mussel abundance and their host fish abundance in Bogue Chitto Creek, a tributary of the Alabama River and a biodiversity hotspot. Mussel abundance de- clined by ~80% and community composition shifted, with eight species previously recorded not found in 2019, and a single individual of the endangered Pleurobema decisum. Fish abundances increased and life history strategies in the community appeared stable and there was no apparent relationship between mussel declines and abundance of host fish. Temporal variation in the pro- Citation: Sanchez Gonzalez, I.; portion of life history traits composing mussel assemblages was also indicative of the disturbances Hopper, G.W.; Bucholz, J.; Atkinson, specifically affecting the mussel community. -

Evolution of Active Host-Attraction Strategies in the Freshwater Mussel Tribe Lampsilini (Bivalvia: Unionidae)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41 (2006) 195–208 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Evolution of active host-attraction strategies in the freshwater mussel tribe Lampsilini (Bivalvia: Unionidae) David T. Zanatta ¤, Robert W. Murphy Royal Ontario Museum, Department of Natural History, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ont., Canada M5S 2C6 Received 17 October 2005; revised 21 May 2006; accepted 22 May 2006 Available online 3 June 2006 Abstract Most freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionoida) require a host, usually a Wsh, to complete their life cycle. Most species of mussels show adaptations that increase the chances of glochidia larvae contacting a host. We investigated the evolutionary relationships of the freshwa- ter mussel tribe Lampsilini including 49 of the approximately 100 extant species including 21 of the 24 recognized genera. Mitochondrial DNA sequence data (COI, 16S, and ND1) were used to create a molecular phylogeny for these species. Parsimony and Bayesian likeli- hood topologies revealed that the use of an active lure arose early in the evolution of the Lampsiline mussels. The mantle Xap lure appears to have been the Wrst to evolve with other lure types being derived from this condition. Apparently, lures were lost independently in sev- eral clades. Hypotheses are discussed as to how some of these lure strategies may have evolved in response to host Wsh prey preferences. © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Freshwater mussels; Host-attraction strategies; Lures; Unionoida; Lampsilini; Phylogenetic systematics 1. Introduction Mantle lures in these species are useful to attract preda- cious Wsh since several species of Lampsilis (e.g., L. siliquoi- Freshwater mussels (also known as unionids, naiads, or dea, L.