People's Perception of Channelization of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleistocene History of a Part of the Hocking River Valley, Ohio1

PLEISTOCENE HISTORY OF A PART OF THE HOCKING RIVER VALLEY, OHIO1 WILLIAM M. MERRILL Department of Geology, University of Illinois, Urbana Drainage modifications caused by glaciation in the Ohio River basin have been the subjects of numerous papers since late in the nineteenth century. Tight (1900, 1903) and Leverett (1902) were the first to present a coordinated picture of the pre-glacial drainage and the successive changes that occurred as a result of the several glacial advances into Ohio. Many shorter papers, by the same and other OHIO writers, were published before and after these volumes. More recently, Stout and Lamb (1938) and Stout, Ver Steeg, and Lamb (1943) presented summaries of the drainage history of Ohio. These are based in part upon Tight's work but also introduce many new facts and give a more detailed account of the sequence of Published by permission of the Chief, Division of Geological Survey, Ohio Department of Natural Resources. THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE 53(3): 143, May, 1953. 144 WILLIAM M. MERRILL Vol. LIII drainage changes and their causal factors. The bulletin published by Stout, et al. (1943, pp. 98-106), includes a comprehensive bibliography of the literature through 1942. Evidence for four major stages of drainage with intervening glacial stages has been recognized in Ohio by Stout, et al. (1938; 1943). These stages have been summarized in columns 1-4, table 1. According to these writers (1938, pp. 66, 73, 76, 81; 1943, pp. 63, 83, 87, 96), all of the stages are represented in the Hocking Valley. The Hocking Valley chronology and the evidence presented by Stout and his co-workers for the several stages in Hocking County are included in columns 5-9, table 1. -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

February 3, 1975 To: Senior Administrators From: Robert E

OHIO UNIVERSITY ATHENS, OHIO 45701 BOARD OF TRUSTEES February 3, 1975 To: Senior Administrators From: Robert E. Mahn, Secretary Re: Draft of January 18 Board Minutes Please report to me errors in the text by February 7. Supporting documents (those appearing in the agenda) are excluded from this draft, but will all be included in the official minutes. You need not return this draft. C72-0 REM:ed 4,1to 5 to P "P-Al fr..4L •/ ee„, lkje" /c< &ba\ 0-7 774,010\-4) ett; dte ,a, ; en, „I/4 Arc ct,"..r1 crvvi. Czo= c r__1.)z-7 , 41,1.6,19___,..e_tf _c -r. .„(__e_c 2 7174,-c_a_ 7-- 4174 t? .2_a t.-_.>-( r--e-----yr /IA ) ' c_e_<,-,-1 0 7M-- --J--°/€- / 3,_45 CID 4 -S- 1 t-- 5) 0-0261 2 PP (71; 7 - ea • tlei,,JAA:ri, c,■-tce:(1) - am_ t7gs---,___rt_ __ LArcIAL. 1-a-ast t_aor,f±, eza- accen-ovtl, ele2.010e-ega o ;77- t_w-ezt- .,Le„arizjz Liet-t-r • 1 AcAti_ c--evt-1 nn-L...wat opeat 44-1 ._a6tc--e:Ap At-ez_ (6,4 a r - • I • 1 •(0 c tnny—A kL,t—e-C A-01/ /2-C , e lug C co-e-/e-e tec A.ArciA/ cran--er/ n ,rzem af.frea„.. k Ma1 rAa---:41111. Meat= A a a-Ak II ciL e /Lc Atcce_t____„t lre_d (4.z.teid- )ItA64.- ciTCPI CM1 (kt)-LijAy,c2311 icAted Kt./ r. • 04%w-re -2 C-- , c, „ AD- 0 e e ; gr cr,A c xiirentL-e_._ —7/ outrkti-c.4_,?Lv-ez, -a 1: CAr14A-11 ,r- • 4 - cv Aacc ok.c, titc /4 56-27 -6-4z,- 4A--ef fr. -

A STORY of the WASHINGTON COUNTY UNORGANIZED TERRITORIES Prepared by John Dudley for Washington County Council of Governments March 2017

A STORY OF THE WASHINGTON COUNTY UNORGANIZED TERRITORIES Prepared by John Dudley for Washington County Council of Governments March 2017 The story of the past of any place or people is a history, but this story is so brief and incomplete, I gave the title of “A Story”. Another person could have written quite a different story based on other facts. This story is based on facts collected from various sources and arranged in three ways. Scattered through one will find pictures, mostly old and mostly found in the Alexander- Crawford Historical Society files or with my families’ files. Following this introduction is a series on pictures taken by my great-grandfather, John McAdam Murchie. Next we have a text describing the past by subject. Those subjects are listed at the beginning of that section. The third section is a story told by place. The story of each of the places (32 townships, 3 plantations and a couple of organized towns) is told briefly, but separately. These stories are mostly in phrases and in chronological order. The listed landowners are very incomplete and meant only to give names to the larger picture of ownership from 1783. Maps supplement the stories. This paper is a work in progress and likely never will be complete. I have learned much through the research and writing of this story. I know that some errors must have found their way onto these pages and they are my errors. I know that this story is very incomplete. I hope correction and additions will be made. This is not my story, it is our story and I have made my words available now so they may be used in the Prospective Planning process. -

Eьfьs Putnam, and His Pioneer Life in the Northwest

1898.] Rufus Putnam.. 431 EÜFÜS PUTNAM, AND HIS PIONEER LIFE IN THE NORTHWEST. BY SIDNEY CRAWFORD. THE life of General Eufus Putnam is sb intimately con- nected with the history of the first century of our countiy that all the facts concerning it are of interest. It is a most commendable effort which has been put forth, therefore, during the more .recent years, to give his name the place it deserves among the founders of our republic. We boast, and rightly, of our national independence, and associate with it the names of Washington and Jefferson, which have become household words throughout the land ; but, when we come to look more closely into the problem of our national life from the beginning of it down to the present time, we find that one of the most essential factors in its solution was the work of Rufus Putnam. Although a man of humble birth, and never enjoying many of the advan- tages of most of those who were associated with him in the movements of his time, yet, in point of all the sturdj"^ qualities of patriotism, sound judgment and farsighted- ness, he was the peer of them all. To him, it may be safely said, without deti'acting from the fame of any one else, tlie countiy owes its present escape from the bondage of African slavery more than to any other man. Had it not been for his providential leadership, and all that it involved, as is so tersely -written on the tablet in the Putnam Memorial at Rutland, "The United States of America would now be a great siavehold- ing empire." He was the originator of the colony to make the first settlement in the, territory nortliAvest of the Ohio 432 . -

Archaeological Settlement of Late Woodland and Late

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SETTLEMENT OF LATE WOODLAND AND LATE PREHISTORIC TRIBAL COMMUNITIES IN THE HOCKING RIVER WATERSHED, OHIO A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Joseph E. Wakeman August 2003 This thesis entitled ARCHAEOLOGICAL SETTLEMENT OF LATE WOODLAND AND LATE PREHISTORIC TRIBAL COMMUNITIES IN THE HOCKING RIVER WATERSHED, OHIO BY JOSEPH E. WAKEMAN has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences Elliot Abrams Professor of Sociology and Anthropology Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences WAKEMAN, JOSEPH E. M.S. August 2003. Environmental Archaeology Archaeological Settlement of Late Woodland and Late Prehistoric Tribal Communities in the Hocking River Watershed, Ohio ( 72 pp.) Director of Thesis: Elliot Abrams Abstract The settlement patterns of prehistoric communities in the Hocking valley is poorly understood at best. Specifically, the Late Woodland (LW) (ca. A.D. 400 – A.D. 1000) and the Late Prehistoric (LP) (ca. A.D. 1000 – A.D. 1450) time periods present interesting questions regarding settlement. These two periods include significant changes in food subsistence, landscape utilization and population increases. Furthermore, it is unclear as to which established archaeological taxonomic units apply to these prehistoric tribal communities in the Hocking valley, if any. This study utilizes the extensive OAI electronic inventory to identify settlement patterns of these time periods in the Hocking River Watershed. The results indicate that landform selection for habitation by these prehistoric communities does change over time. The data suggest that environmental constraint, population increases and subsistence changes dictate the selection of landforms. -

Fluvial Sediment in Hocking River Subwatershed 1 (North Branch Hunters Run), Ohio

Fluvial Sediment in Hocking River Subwatershed 1 (North Branch Hunters Run), Ohio GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1798-1 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service Fluvial Sediment in Hocking River Subwatershed 1 (North Branch Hunters Run), Ohio By RUSSELL F. FLINT SEDIMENTATION IN SMALL DRAINAGE BASINS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1798-1 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 71-190388 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 30 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-2153 CONTENTS Page Abstract __________________ U Introduction __________ -- 1 Acknowledgments ___ __ 2 Description of the area __ - 3 Elevations and slopes __ ________ 4 Soils and land use ___________ 4 Geology ___________________ 4 Climate __________________ 5 Hydraulic structures _____________ 5 Runoff _________________________________ __ 9 Fluvial sediment ________________ 12 Suspended sediment _____________ 13 Deposited sediment ___________ 19 Sediment yield ______________ 19 Trap efficiency of reservoir 1 _____________ - 21 Conclusions _____________________________________ 21 References _______________________________-- 22 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Map of Hocking River subwatershed 1 (North Branch Hunters Run) __________________________ 13 2-6. Photographs showing 2. Upstream face of detention structure . 6 3. Reservoir 1 ______ 6 4. Minor floodwater-retarding structure R3 7 5. Minor sediment-control structure S4 7 6. Outflow conduit of reservoir 1.___ 13 7. Trilinear diagram showing percentage of sand, silt, and clay in suspended-sediment samples of inflow and out flow, reservoir 1 ___________-_____ 15 TABLES Page TABLE 1. -

Basin Descriptions and Flow Characteristics of Ohio Streams

Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Water BASIN DESCRIPTIONS AND FLOW CHARACTERISTICS OF OHIO STREAMS By Michael C. Schiefer, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Water Bulletin 47 Columbus, Ohio 2002 Robert Taft, Governor Samuel Speck, Director CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………. 2 Purpose and Scope ……………………………………………………………. 2 Previous Studies……………………………………………………………….. 2 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………… 3 Factors Determining Regimen of Flow………………………………………………... 4 Weather and Climate…………………………………………………………… 4 Basin Characteristics...………………………………………………………… 6 Physiology…….………………………………………………………… 6 Geology………………………………………………………………... 12 Soils and Natural Vegetation ..………………………………………… 15 Land Use...……………………………………………………………. 23 Water Development……………………………………………………. 26 Estimates and Comparisons of Flow Characteristics………………………………….. 28 Mean Annual Runoff…………………………………………………………... 28 Base Flow……………………………………………………………………… 29 Flow Duration…………………………………………………………………. 30 Frequency of Flow Events…………………………………………………….. 31 Descriptions of Basins and Characteristics of Flow…………………………………… 34 Lake Erie Basin………………………………………………………………………… 35 Maumee River Basin…………………………………………………………… 36 Portage River and Sandusky River Basins…………………………………….. 49 Lake Erie Tributaries between Sandusky River and Cuyahoga River…………. 58 Cuyahoga River Basin………………………………………………………….. 68 Lake Erie Tributaries East of the Cuyahoga River…………………………….. 77 Ohio River Basin………………………………………………………………………. 84 -

Wetlands in Teays-Stage Valleys in Extreme Southeastern Ohio: Formation and Flora

~ Symposium on Wetlands of th'e Unglaclated Appalachian Region West Virginia University, Margantown, W.Va., May 26-28, 1982 Wetlands in Teays-stage Valleys in Extreme Southeastern Ohio: Formation and Flora David ., M. Spooner 1 Ohio Department of Natural Resources Fountain Square, Building F Columbus, Ohio 43224 ABSTRACT. A vegetational survey was conducted of Ohio wetlands within an area drained by the preglacial Marietta River (the main tributary of the Teays River in southeastern Ohio) and I along other tributaries of the Teays River to the east of the present-day Scioto River and south of the Marietta River drainage. These wetlands are underlain by a variety of poorly drained sediments, including pre-Illinoian lake silts, Wisconsin lake silts, Wisconsin glacial outwash, and recent alluvium. A number of rare Ohio species occur in these wetlands. They include I Potamogeton pulcher, Potamogeton tennesseensis, Sagittaria australis, Carex debilis var. debilis, Carex straminea, Wo(f(ia papu/({era, P/atanthera peramoena, Hypericum tubu/osum, Viola lanceo/ata, Viola primu/({o/ia, HO/lonia in/lata, Gratio/a virginiana, Gratiola viscidu/a var shortii and Utriculariagibba. In Ohio, none of thesewetlandsexist in their natural state. ~ They have become wetter in recent years due to beaver activity. This beaver activity is creating J open habitats that may be favorable to the increase of many of the rare species. The wetlandsare also subject to a variety of destructive influences, including filling, draining, and pollution from adjacent strip mines. All of the communities in these wetlands are secondary. J INTRODUCTION Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, 1982. -

Part I: General Information

PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION Name of Institution: Ohio University Name of Unit: E.W. Scripps School of Journalism Year of Visit: 2013 1. Check regional association by which the institution now is accredited. ___ Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools ___ New England Association of Schools and Colleges _x_ North Central Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges ___ Southern Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Western Association of Schools and Colleges 2. Indicate the institution’s type of control; check more than one if necessary. ___ Private _x_ Public ___ Other (specify) 3. Provide assurance that the institution has legal authorization to provide education beyond the secondary level in your state. It is not necessary to include entire authorizing documents. Public institutions may cite legislative acts; private institutions may cite charters or other authorizing documents. In 1786, Manasseh Cutler and Rufus Putnam helped establish the Ohio Company, whose petition to Congress resulted in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. This ordinance provided for the settlement of the Northwest Territory. Ohio University was established in 1804 as the first institution of higher learning in the Northwest Territory. Ohio University is accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools to award associate, bachelor, master and doctoral degrees. 4. Has the journalism/mass communications unit been evaluated previously by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications? _x_ Yes ___ No If yes, give the date of the last accrediting visit: 2006-2007 Ohio University, E. W. Scripps School of Journalism – Team Report – page 2 of 39 5. -

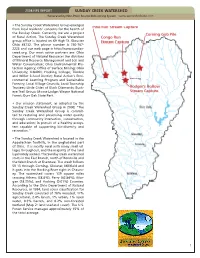

SUNDAY CREEK WATERSHED Generated by Non-Point Source Monitoring System

2008 NPS REPORT SUNDAY CREEK WATERSHED Generated by Non-Point Source Monitoring System www.watersheddata.com • The Sunday Creek Watershed Group emerged from local residents’ concerns for the health of the Sunday Creek. Currently, we are a project of Rural Action. The Sunday Creek Watershed group office is located on 69 High St. Glouster Ohio 45732. The phone number is 740-767- 2225 and our web page is http://www.sunday- creek.org. Our most active partners are: Ohio Department of Natural Resources the divisions of Mineral Resource Management and Soil and Water Conservation; Ohio Environmental Pro- tection Agency; Office of Surface Mining; Ohio University; ILGARD; Hocking College; Trimble and Miller School District; Rural Action’s Envi- ronmental Learning Program and Sustainable Forestry; Local Village Councils; Local Township Trustees; Little Cities of Black Diamonds; Buck- eye Trail Group; Moose Lodge; Wayne National Forest; Burr Oak State Park. • Our mission statement, as adopted by the Sunday Creek Watershed Group in 2000; “The Sunday Creek Watershed Group is commit- ted to restoring and preserving water quality through community interaction, conservation, and education; in pursuit of a healthy ecosys- tem capable of supporting bio-diversity and recreation.” • The Sunday Creek Watershed is located in the Appalachian foothills, in the unglaciated part of Ohio. It is mostly rural with many small vil- lages throughout, and the majority of the land is privately owned. The Sunday creek watershed starts in the East Branch, north of Rendville and the West Branch at Shawnee. The creek follows SR 13 through Corning, Glouster, Millfield and it goes into the Hocking River right in Chaunc- ey. -

2018-19 Site Team Report

PART I: General information Name of Institution: Ohio University Name of Unit: E.W. Scripps School of Journalism Year of Visit: 2018 1. Check regional association by which the institution now is accredited. ___ Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools ___ New England Association of Schools and Colleges X North Central Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Northwest Association of Schools and Colleges ___ Southern Association of Colleges and Schools ___ Western Association of Schools and Colleges If the unit seeking accreditation is located outside the United States, provide the name(s) of the appropriate recognition or accreditation entities: 2. Indicate the institution’s type of control; check more than one if necessary. ___ Private X Public ___ Other (specify) 3. Provide assurance that the institution has legal authorization to provide education beyond the secondary level in your state. It is not necessary to include entire authorizing documents. Public institutions may cite legislative acts; private institutions may cite charters or other authorizing documents. In 1786, Manasseh Cutler and Rufus Putnam helped establish the Ohio Company, whose petition to Congress resulted in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. This ordinance provided for the settlement of the Northwest Territory as well as the establishment of Ohio University, which subsequently was chartered in 1804 as the first institution of higher learning in this new territory. The university is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission (HLC), formerly the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, to award associate, bachelor, master and doctoral degrees. 4. Has the journalism/mass communications unit been evaluated previously by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications? _X_Yes ___ No If yes, give the date of the last accrediting visit: January 2013 5.