Dub Techno's Hauntological Politics of Acoustic Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electro House 2015 Download Soundcloud

Electro house 2015 download soundcloud CLICK TO DOWNLOAD TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Lala bon. TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Yeaa sa pette. TZ. Users who like Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Users who reposted Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Playlists containing Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix Electro House by EDM Joy. Part of @edmjoy. Worldwide. 5 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Electro House @ EDM Joy on your desktop or mobile device. An icon used to represent a menu that can be toggled by interacting with this icon. Best EDM Remixes Of Popular Songs - New Electro & House Remix; New Electro & House Best Of EDM Mix; New Electro & House Music Dance Club Party Mix #5; New Dirty Party Electro House Bass Ibiza Dance Mix [ FREE DOWNLOAD -> Click "Buy" ] BASS BOOSTED CAR MUSIC MIX BEST EDM, BOUNCE, ELECTRO HOUSE. FREE tracks! PLEASE follow and i will continue to post songs:) ALL CREDIT GOES TO THE PRODUCERS OF THE SONG, THIS PAGE IS FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY I WILL ONLY POST SONGS THAT ARE PUT UP FOR FREE. 11 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Free Electro House on your desktop or mobile device. Listen to the best DJs and radio presenters in the world for free. Free Download Music & Free Electronic Dance Music Downloads and Free new EDM songs and tracks. Get free Electro, House, Trance, Dubstep, Mixtape downloads. Exclusive download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Click here to download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Maximise Network, Eric Clapman and GANGSTA-HOUSE on Soundcloud Follow +1 entry I've already followed Maximise Music, Repost Media, Maximise Network, Eric. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Course Syllabus Live-Performance Disc Jockey Techniques 3 Credits

Course Syllabus Live-Performance Disc Jockey Techniques 3 Credits MUC135, Section 33575 Scottsdale Community College, Department of Music Fall 2015 (September 1 to December 18, 2015) Tuesday Evenings 6:30 PM - 9:10 PM (Room MB-136) Instructor: Rob Wegner, B.S., M.A. ([email protected] or [email protected]); Cell: 480-695-6270 Office Hours: Monday’s 6:00 - 7:30PM (Room MB-139) Recommended Text: How to DJ Right: The Art and Science of Playing Records by Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton (Grove Press, 2003). ISBN: 0-8021- 3995-7 Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop DJ by Mark Katz (Oxford University Press, 2012). ISBN-10: 0195331125 Recommended DVD: Scratch: A Film by Doug Prey by Doug Prey (Palm Pictures, 2001). Required Gear: Headphones (for labs) Additional Suggested Reading: Off the Record by Doug Shannon (1982), Pacesetter Publishing House. Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, The History of the Disc Jockey by Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton (2000), Grove Press. On The Record: The Scratch DJ Academy Guide by Phil White & Luke Crisell (2009), St. Martin’s Griffin. Looking for the Perfect Beat by Kurt B. Reighley (2000), Pocket Books. How to Be a DJ by Chuck Fresh (2001), Brevard Marketing. DJ Culture by Ulf Poschardt (1995), Quartet Books Limited. The Mobile DJ Handbook, 2nd Edition by Stacy Zemon (2003), Focal Press. Turntable Basics by Stephen Webber (2000), Berklee Press. Course Objectives Upon successful completion of this course, you should be able to: explain the historical innovations that led to the evolution of -

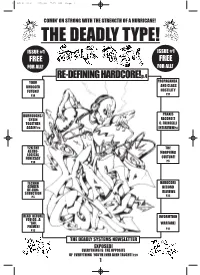

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1 COMINÕ ON STRONG WITH THE STRENGTH OF A HURRICANE! THE DEADLY TYPE! ISSUE #1 ISSUE #1 FREE FREE FOR ALL!L FOR ALL!L RE-DEFINING HARDCORE!p.4 YOUR PROPAGANDA DRUGGED AND CLASS FUTURE! HOSTILITY P.14 P.11 BURROUGHS/ PRAXIS GYSIN RECORD'S TOGETHER C. FRINGELLI AGAIN! P.6 INTERVIEWP.8 Y2K:THE THE ASTRO- MORPHING LOGICAL FORECAST CULTURE! P.10 P.5 TECHNO HARDCORE GENDER RECORD DE-CON- STRUCTION REVIEWS P.5 P.16 READ BEFORE INFORMTION YOU GO...A "JAIL WARFARE! PRIMER! P.12 P.13 THE DEADLY SYSTEMS NEWSLETTER EXPOSED! EVERYTHING IS THE OPPOSITE OF EVERYTHING YOU'VE EVER BEEN TAUGHT! P.29 1 DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 2 money. So you could say that the rave scene was truly assimilated on just about all fronts by the mainstream. This WHY THE aggravated a problem of mis-concep- tion for the music itself . Most people being introduced to Hardcore had no idea about the ideas surrounding it-or DEADLY that there even were any! To most peo- ple, even a few making music they claimed was “hardcore”, it was just fast, noizy, and supposed to piss you off. This is retarded. Nothing can be further TYPE? from the truth, and that is why “The Deadly Type” exists today, to re-define Hardcore. Firstly, “RE” as to do it again, -by Deadly Buda as people are not even aware of it’s influences, history or forgot the entire The original reason for this social context. -

October 08 to 15, 2011 Marco Bruzzone Colli

October 08 to 15, 2011 Marco Bruzzone Colli Opening: October 08, 2011, 7pm Galleria collicaligreggi is proud to present the first solo show by Marco Bruzzone in Italy. Marco Bruzzone has lived for more than ten years in Berlin, where he works as an artist as well as curator, cook and DJ. His artistic practice is interdisciplinary – many of his works are of a transitory nature, such as a meeting or collaboration with other artists, and often become visible only at certain moments. In 2007, Bruzzone used stencils to spray the phrase “Less is cool“ on the wall just above the floor of the exhibition space (The importance not to be seen, Café Moskau/Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin 2007). Instead of spray paint, however, he used spray glue. The statement first became legible over the course of time as dust collected in the room. Marco Bruzzone’s diverse works are unified by a sense of lightness and reduction, as well as a consistent rejection of grand artistic gestures. At galleria collicaligreggi the artist presents his new project Colli [engl. necks], which deals with the change of seasons from hot summer to autumn. In his installation of images, music, poetry and flowers, Bruzzone examines the shift from a time of leisurely distraction to the reality of everyday life. For the exhibition he stretched beach towels across frames like canvases: through their differing wear and tear and their printed or woven motifs they recall personal and collective memories. For some time now, Bruzzone has addressed issues of painting, examining its surface structures and forms of representation with unusual materials. -

Nna Luke Abbott : Biography

nna luke abbott : biography It was towards the end of 2010 when Norfolk's self-styled ambassador of art school electronica Luke Abbott first unveiled the lush organic textures and pagan hypnotics of 'Holkham Drones', his ever-so- slightly-wonky debut album that takes its name from a beach on Norfolk's surprisingly northern section of coast. In the intervening months that have since elapsed, the unassuming twelve track collection of handcrafted hardware-jams has won over convert upon convert, staking a claim alongside recent releases from Four Tet and Gold Panda as one of the definitive works of the UK's ever-bolder Kraut- tinged corner of the dance music spectrum, as well as making serious inroads with the Drowned In Sound indie set, for whom the “game-changing electronic opus” stood out as “far and away one of DiS' favourite records of 2010”. Luke Abbott spent his formative years in the Norfolk fenland village of North Lopham, surrounded by records lovingly hoarded by his pop music historian father Kingsley, author of biographical tomes encompassing Sixties luminaries such as The Beach Boys and Phil Spector. Luke first headed towards the bright lights of Norwich to enrol at the city's respected art school, soon followed by a course in Electroacoustic Composition at the UEA. Here the university's open-minded approach would allow him to indulge all of his technological curiosities, wandering at will down the various experimental avenues that run through electronic music's leftfield. This hands-on and homemade DIY approach has continued to inform his fledgling steps into a musical career, from circuit-bending and hardware-hacking to generating bespoke software instruments and sequencers and building his own custom MIDI controller. -

A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music with Ellen Allien

Editorial A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music With Ellen Allien Kian McHugh | August 3, 2020 When my Zoom call with Ellen Allien connects, at last, I feel weeks of anticipation turn to uncontrollable excitement. My fingers, sweaty from nerves, and a poorly brewed Starbucks coffee, type out the instructions on how to get her audio configured. Ellen is lounging in her Ibiza flat where she has painted all of the walls completely black so that when the sun shines through her window, the room glows yellow. The first fully formed thought I could pencil down was that her posture seemed to denote a sincere attention to detail and confidence in comfort that most others lack. For the first 2 minutes of the call, we both instinctively laugh, muted, and unaware that our discussion of Techno would soon gravitate toward, and then find unexpected momentum in… a deep consideration of Techno, God, and religion. “Rap is where you rst heard it… If rap is more an American phenomenon, techno is where it all comes together in Europe as producers and musicians engage in a dialogue of dazzling speed.” – Jon Savage (English writer, broadcaster and music journalist). In Hanif Abdurraqib’s 2019 book, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, he so beautifully praises “the low end” of a track: “The feeling of something familiar that sits so deep in your chest that you have to hum it out … where the bass and the kick drums exist.” His point rings true across all music that is heavily percussion driven. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

Detroit's Maritime Techno Underground

Detroit’s maritime techno underground. On the relationship between the 18th century pirates movement and concepts of social utopias, ideology, and cultural production in Detroit techno. A proseminar-paper for PS Cultural and Media Studies, course title: Pirates in (US-)American Culture, conducted by Mag.a Dr.in Alexandra Ganser, WS 2014/2015, by Christian Hessle, matriculation number: 9450392, e-mail: [email protected] due to 1 March 2015, 3676 words. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................3 2. Double consciousness....................................................................................................3 3. The black Atlantic..........................................................................................................4 4. The ancestors of Detroit techno: Funk, Fusion Jazz, and Afrofuturism........................5 5. The Belleville Three......................................................................................................6 6. The factory: from the ship to the city............................................................................6 7. Underground Resistance................................................................................................7 8. Drexciya.......................................................................................................................10 9. Conclusion...................................................................................................................12 -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy.