Clydesdale's Heritage an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tweed Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan INTERIM REPORT

Tweed Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Tweed Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan INTERIM REPORT Published by: Scottish Borders Council Lead Local Authority Tweed Local Plan District 01 March 2019 In partnership with: Tweed Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Publication date: 1 March 2019 Terms and conditions Ownership: All intellectual property rights of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are owned by Scottish Borders Council, SEPA or its licensors. The INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan cannot be used for or related to any commercial, business or other income generating purpose or activity, nor by value added resellers. You must not copy, assign, transfer, distribute, modify, create derived products or reverse engineer the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan in any way except where previously agreed with Scottish Borders Council or SEPA. Your use of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan must not be detrimental to Scottish Borders Council or SEPA or other responsible authority, its activities or the environment. Warranties and Indemnities: All reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan is accurate for its intended purpose, no warranty is given by Scottish Borders Council or SEPA in this regard. Whilst all reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are up to date, complete and accurate at the time of publication, no guarantee is given in this regard and ultimate responsibility lies with you to validate any information given. -

1. Introduction and Pipeline Legislation

1. INTRODUCTION AND PIPELINE LEGISLATION Introduction 1.1. Bord Gáis Eireann propose to construct a new pipeline between Beattock, Scotland and Gormanston, Ireland. The project is called ‘Scotland to Ireland – The Second Gas Interconnector.’ The pipeline will provide additional capacity to supply Ireland with natural gas from the North Sea and other international gas reserves via the existing Transco pipeline network. 1.2. The main elements of the project include an extension to Beattock Compressor Station, a new pipeline between Beattock and Brighouse, an extension to Brighouse Compressor Station and a new sub-sea pipeline between Brighouse and Gormanston. 1.3. This Environmental Statement examines the potential interaction between the Scottish Land Pipeline and the environment. The Scottish Land Pipeline will be constructed between Beattock and Brighouse. The land pipeline system will comprise a 36 inch (914mm) diameter pipeline approximately 50miles in length, and four Block Valve Stations (BV’s). The proposed pipeline route is shown in Figure 1.2. Background 1.4. Bord Gáis Eireann and the Irish Department of Public Enterprise initiated a project called Gas 2025 in November 1997, to plan the possible need for further transmission pipelines to meet forecast growth in demand to the year 2025. 1.5. In Ireland, gas is sourced from the Kinsale Head Gas Field off the south east coast, and the existing Interconnector pipeline. The Kinsale Head Gas Field is now in final depletion, placing increasing importance on the Interconnector pipeline. This first Interconnector pipeline was constructed in 1993 and runs from Beattock in Dumfries and Galloway, through to Loughshinny in Ireland. -

6 Cook: Howe Mire, Inveresk | 143

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 134 (2004), 131–160 COOK: HOWE MIRE, INVERESK | 131 Howe Mire: excavations across the cropmark complex at Inveresk, Musselburgh, East Lothian Murray Cook* with contributions from A Heald, A Croom and C Wallace ABSTRACT Excavations across the complex of cropmarks at Inveresk, Musselburgh, East Lothian (NGR: NT 3540 7165 to NT 3475 7123), revealed a palimpsest of features ranging in date from the late Mesolithic to the Early Historic period. The bulk of the features uncovered were previously known from cropmark evidence and are connected with either the extensive field system associated with the Antonine Fort at Inveresk or the series of Roman marching camps to the south-west of the field system. The excavation has identified a scattering of prehistoric activity, as well as Roman settlement within the field system, together with dating evidence for one of the marching camps and structures reusing dressed Roman stone. INTRODUCTION reports have been included in the site archive. A brief summary of these excavations has been An archaeological watching brief was previously published (Cook 2002a). conducted in advance of the construction of This report deals solely with the excavated 5km of new sewer pipeline from Wallyford to area within the scheduled areas which com- Portobello (NT 3210 7303 to NT 3579 7184). prised a 6m wide trench approximately 670m The construction works were conducted by M J long (illus 1) (NT 3540 7165 to NT 3475 7123). Gleeson Group plc on behalf of Stirling Water. The trench was located immediately to the The route of the pipeline ran through a series south of the Edinburgh to Dunbar railway line of cropmarks to the south of Inveresk (illus (which at this point is in a cutting) and crossed 1; NMRS numbers NT 37 SE 50, NT 37 SW both Crookston and Carberry Roads, Inveresk, 186, NT 37 SW 33, NT37 SW 68 and NT 37 Musselburgh. -

Network Development Plan 2016 Assessing Future Demand and Supply Position Table of Contents Network Development Plan 2016

gasnetworks.ie Network Development Plan 2016 assessing future demand and supply position Table of Contents NETWORK DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2016 1. Foreword 2 6.3 COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS IN TRANSPORT 46 2. Executive Summary 4 6.4 RENEWABLE GAS 48 3. Introduction 6 6.5 ELECTRICITY SECTOR 51 3.1 OVERVIEW OF THE GAS NETWORKS IRELAND SYSTEM 8 3.2 INVESTMENT INFRASTRUCTURE 10 7. System Operation 52 3.3 HISTORIC DEMAND & SUPPLY 11 7.1 CHALLENGES 54 7.1.1 Demand Variation 55 3.3.1 ROI Annual Primary Energy Requirement 11 3.3.2 Historic Annual Gas Demand 12 8. Projects of Common Interest & 3.3.3 Historic Peak Day Gas Demand 13 Security of Gas Supply 56 3.3.4 Ireland’s Weather 13 8.1 PROJECTS OF COMMON INTEREST (PCI) 57 3.3.5 Wind Powered Generation 14 8.2 PHYSICAL REVERSE FLOW AT MOFFAT 58 3.3.6 Electricity Interconnectors 14 8.3 EUROPEAN REGULATION 994/2010 58 3.3.7 Historic Gas Supply 15 8.4 EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS 59 4. Gas Demand Forecasts 16 9. Commercial Market Arrangements 60 4.1 GAS DEMANDS 17 9.1 REPUBLIC OF IRELAND GAS MARKET 61 4.1.1 Gas Demand Forecasting 18 9.2 EUROPEAN DEVELOPMENTS 62 4.2 GAS DEMAND SCENARIOS 20 9.2.1 Capacity Allocation Mechanism 62 4.3 DEMAND FORECAST ASSUMPTIONS 21 9.2.2 Joint Capacity Booking Platform 63 4.3.1 Power Generation Sector 21 9.2.3 Congestion Management Procedures 63 4.3.2 Industrial & Commercial Sector 23 9.2.4 Balancing 63 4.3.3 Residential Sector 24 9.2.5 Tariffs 64 4.3.3.1 Energy Efficiency 25 9.2.6 REMIT 65 4.3.4 Compressed Natural Gas For Transport 25 9.2.7 Transparency 65 4.4 THE DEMAND OUTLOOK 26 4.4.1 Power Generation Sector Gas Demand 26 4.4.2 Industrial & Commercial Sector Gas Demand 27 10. -

South Lanarkshire Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy

South Lanarkshire Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy Report by IronsideFarrar 7948 / February 2016 South Lanarkshire Council Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 3.3 Landscape Designations 11 3.3.1 National Designations 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page No 3.3.2 Local and Regional Designations 11 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 3.4 Other Designations 12 1.1 Background 1 3.4.1 Natural Heritage designations 12 1.2 National and Local Policy 2 3.4.2 Historic and cultural designations 12 1.3 The Capacity Study 2 3.4.3 Tourism and recreational interests 12 1.4 Landscape Capacity and Cumulative Impacts 2 4.0 VISUAL BASELINE 13 2.0 CUMULATIVE IMPACT AND CAPACITY METHODOLOGY 3 4.1 Visual Receptors 13 2.1 Purpose of Methodology 3 4.2 Visibility Analysis 15 2.2 Study Stages 3 4.2.1 Settlements 15 2.3 Scope of Assessment 4 4.2.2 Routes 15 2.3.1 Area Covered 4 4.2.3 Viewpoints 15 2.3.2 Wind Energy Development Types 4 4.2.4 Analysis of Visibility 15 2.3.3 Use of Geographical Information Systems 4 5.0 WIND TURBINES IN THE STUDY AREA 17 2.4 Landscape and Visual Baseline 4 5.1 Turbine Numbers and Distribution 17 2.5 Method for Determining Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity 4 5.1.1 Operating and Consented Wind Turbines 17 2.6 Defining Landscape Change and Cumulative Capacity 5 5.1.2 Proposed Windfarms and Turbines (at March 2015) 18 2.6.1 Cumulative Change -

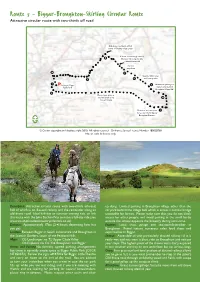

Biggar-Broughton-Skirling Circular Route Attractive Circular Route with Two-Thirds Off Road

Route 5 - Biggar-Broughton-Skirling Circular Route Attractive circular route with two-thirds off road Old drove road leads off NE corner of Skirling village green If drove road through trees is 8 blocked, ride along the side of the adjacent field Ford or jump burn 10 7 Beware rabbit holes 9 6 and loose ponies 1 PParking at Biggar 5 Alternative parking for Public Park trailers only behind Broughton Village Hall 2 Please leave gates as you find them along 4 disused railway Dismount and lead your 3 horse over the bridge by Broughton Brewery N © Crown copyright and database right 2010. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence Number 100020730 Not to scale. Indicative only. Description: Attractive circular route with two-thirds off-road, up dung. Limited parking in Broughton village other than the half of which is on disused railway and the remainder along an car park behind the village hall, which is across a narrow bridge old drove road. Ideal half-day or summer evening ride, or link unsuitable for lorries. Please make sure that you do not block this route with the John Buchan Way to make a full-day ride (see access for other people, and avoid parking in the small lay-by www.southofscotlandcountrysidetrails.co.uk). outside the school opposite the brewery during term-time. Distance: Approximately 17km (2-4 hours, depending how fast Facilities: Local shop, garage and tea-room/bistro/bar in you go). Broughton. Petrol station, numerous cafes, food shops and Location: Between Biggar in South Lanarkshire and Broughton in supermarket in Biggar. -

Hand-Book of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre, and Uddingston. with a Directory

; Hand-Book HAMILTON, BOTHWELL, BLANTYRE, UDDINGSTON W I rP H A DIE EJ C T O R Y. ILLUSTRATED BY SIX STEEL ENGRAVINGS AND A MAP. AMUS MACPHERSON, " Editor of the People's Centenary Edition of Burns. | until ton PRINTED AT THE "ADVERTISER" OFFICE, BY WM. NAISMITH. 1862. V-* 13EFERKING- to a recent Advertisement, -*-*; in which I assert that all my Black and Coloured Cloths are Woaded—or, in other wards, based with Indigo —a process which,, permanently prevents them from assuming that brownish appearance (daily apparent on the street) which they acquire after being for a time in use. As a guarantee for what I state, I pledge myself that every piece, before being taken into stock, is subjected to a severe chemical test, which in ten seconds sets the matter at rest. I have commenced the Clothing with the fullest conviction that "what is worth doing is worth doing well," to accomplish which I shall leave " no stone untamed" to render my Establishment as much a " household word " ' for Gentlemen's Clothing as it has become for the ' Unique Shirt." I do not for a moment deny that Woaded Cloths are kept by other respectable Clothiers ; but I give the double assurance that no other is kept in my stock—a pre- caution that will, I have no doubt, ultimately serve my purpose as much as it must serve that of my Customers. Nearly 30 years' experience as a Tradesman has convinced " me of the hollowness of the Cheap" outcry ; and I do believe that most people, who, in an incautious moment, have been led away by the delusive temptation of buying ' cheap, have been experimentally taught that ' Cheapness" is not Economy. -

Community and Enterprise Resources Planning and Economic Development Services Weekly List of Planning Applications List of Plann

Community and Enterprise Resources Planning and Economic Development Services Weekly List of Planning Applications List of planning applications registered by the Council for the week ending From : - 29/10/2018 To : 02/11/2018 The Planning Weekly List contains details of planning applications and proposals of application notices registered in the previous week. Note to Members: Proposal of application notices A ‘proposal of application notice’ is a notice that must be submitted to the Council, by the developer, at least 12 weeks before they submit an application for a major development. The notice explains what the proposal is and sets out what pre-application consultation they will carry out with the local community. Please note that at this stage, any comments which the public wish to make on such a notice should be made directly to the applicant or agent, not to the Council. If, however, any of the proposals described on the list as being a proposal of application notice raise key issues that you may wish to be considered during their future assessment, please contact the appropriate team leader/area manager within 10 days of the week-ending date at the appropriate area office. Planning applications If you have any queries on any of the applications contained in the list, please contact the appropriate team leader/area manager within 10 days of the week-ending date at the appropriate office. Applications identified as 'Delegated' shall be dealt with under these powers unless more than 5 objections are received. In such cases the application will be referred to an appropriate committee. -

South Lanarkshire Council Present

South Lanarkshire Council South Lanarkshire Local RAUC Meeting, 19 August 2020 – Meeting No. 45 Present: David Carter DC South Lanarkshire Council (Chair) Valerie Park VP South Lanarkshire Council Graeme Peacock GP SGN Glasgow Stewart Allan SA AMEY M8/M73/M74/DBFO David Fleming DF TTPAG DBFO David Murdoch DM Network Rail Emma West EW Scottish Water Collette Findlay CF SGN Coatbridge Joao Carmo JC SPEN John McCulloch JMcC Balfour Beatty Owen Harte OH Virgin Media Stephen Scanlon SS OpenReach Steven McGill SMcG Fulcrum Neil Brannock NB Autolink M6 Scott Bunting SB SSE Craig McTiernan CMcT Axione Gordon Michie GM Scottish Water Note – apologies were received but not noted. Additional Circulation to: George Bothwick Action No. Description By 1.0 Introductions and Apologies NOTE – These minutes are from 19th February – attendance list accurate for Noted August meeting 2.0 Agree Previous Minutes – 19 February 2020 Minutes agreed from previous meeting as accurate. Noted 3.0 Matters Arising from Previous Minutes Increased numbers of DA and unattributable works notices Noted VP 4.0 Performance 4.1 All OD Performance Page 1 of 6 South Lanarkshire Council South Lanarkshire Local RAUC Meeting, 19 August 2020 – Meeting No. 45 Action No. Description By Outstanding defect report distributed prior to the meeting for discussion. ALL VP noted that in recent months Openreach, Virgin Media and SGN have made good progress in clearing some of their outstanding defects. VP advised that there is an increasing number of Defective Apparatus and Unattributable works notices still recorded against the SL001 channel awaiting acceptance from relevant Utilities (approx. 100). -

The Newsletter of the Tweed Forum

SUMMER 2019 / ISSUE 20 The newsletter of the Tweed Forum Cover image: Winner of the Beautiful River Tweed photo competition (sponsored by Ahlstrom Munksjo), Gillian Watson’s image of the Tweed in autumn o NEWS Tweed Forum Carbon Club e are delighted to announce the launch of the W Tweed Forum Carbon Club. The Club offers the chance, as an individual, family or small business, to offset your carbon footprint by creating new native woodland in the Tweed catchment. Trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and by making a donation you’ll help to create wonderful new woodlands that will enhance the biodiversity, water quality and beauty of the local area and allow you to offset the carbon dioxide you use in your everyday life. Either by monthly subscription or a one-off donation you can help fight climate change and create beautiful native woodlands for future generations to enjoy. www.tweedforum.org/ tweed-forum-carbon-club/ Tweed Forum Director, Luke Comins (left), and Chairman, James Hepburne Scott (right), celebrating the launch of the Tweed Forum Carbon Club Tweed Matters 1 o NEWS ‘Helping it Happen’ Award winners Tweed Forum and Philiphaugh Estate improve water quality and create better were the proud winners of the habitats for wildlife. Funding for the ‘Enhancing our Environment’ prize at project was obtained from a variety of last year’s Helping it Happen Awards. sources including Peatland Action and the The awards, organised by Scottish Land Scottish Rural Development Programme and Estates, recognised our collaborative (SRDP). Carbon finance was also secured restoration of peatland at Dryhope Farm, from NEX Group plc (via Forest Carbon). -

West Coast Main Line North

West Coast Main Line North 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 2 2 A HISTORY .............................................................................................. 2 3 THE ROUTE ............................................................................................. 3 The West Coast Main Line in Railworks ................................................................................... 5 4 ROLLING STOCK ...................................................................................... 6 4.1 Electric Class 86 ............................................................................................................ 6 4.2 Intercity Mk3a Coaches................................................................................................... 6 5 SCENARIOS ............................................................................................. 7 5.1 Free Roam: Carlisle Station ............................................................................................. 7 5.2 Free Roam: Carstairs Station ........................................................................................... 7 5.3 Free Roam: Glasgow Central Station ................................................................................. 7 5.4 Free Roam: Mossend Yard ............................................................................................... 7 5.5 Free Roam Motherwell Station ........................................................................................ -

Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Turbine Development in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley

Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Turbine Development in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Overview Report Prepared by LUC for the Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Plan Authority September 2014 Project Title: Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Turbine Development in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Client: Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Plan Authority In association with: Scottish Natural Heritage East Dunbartonshire Council East Renfrewshire Council Glasgow City Council Inverclyde Council North Lanarkshire Council Renfrewshire Council South Lanarkshire Council West Dunbartonshire Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Principal 0.1 15 November Internal draft LUC PDM NJ 2013 0.2 22 November Interim draft for LUC PDM NJ 2013 discussion 1.0 25 March Draft LUC NJ NJ 2014 2.0 6 June 2014 Final LUC PDM NJ 3.0 11 September Revised LUC PDM NJ 2014 H:\1 Projects\58\5867 LIVE GCV wind farm study\B Project Working\REPORT\Overview report\GCV Report v3 20140911.docx Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Turbine Development in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Overview Report Prepared by LUC for the Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Plan Authority September 2014 Planning & EIA LUC GLASGOW Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 37 Otago Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning Glasgow G12 8JJ Bristol Registered Office: Landscape Management Tel: 0141 334 9595 Edinburgh 43 Chalton Street Ecology Fax: 0141 334 7789 London NW1