I the INFLUENCE of COERCIVE PRESSURE on ASEAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Hancock Emerging Markets Fund

John Hancock Emerging Markets Fund Quarterly portfolio holdings 5/31/2021 Fund’s investments As of 5-31-21 (unaudited) Shares Value Common stocks 98.2% $200,999,813 (Cost $136,665,998) Australia 0.0% 68,087 MMG, Ltd. (A) 112,000 68,087 Belgium 0.0% 39,744 Titan Cement International SA (A) 1,861 39,744 Brazil 4.2% 8,517,702 AES Brasil Energia SA 14,898 40,592 Aliansce Sonae Shopping Centers SA 3,800 21,896 Alliar Medicos A Frente SA (A) 3,900 8,553 Alupar Investimento SA 7,050 36,713 Ambev SA, ADR 62,009 214,551 Arezzo Industria e Comercio SA 1,094 18,688 Atacadao SA 7,500 31,530 B2W Cia Digital (A) 1,700 19,535 B3 SA - Brasil Bolsa Balcao 90,234 302,644 Banco Bradesco SA 18,310 80,311 Banco BTG Pactual SA 3,588 84,638 Banco do Brasil SA 15,837 101,919 Banco Inter SA 3,300 14,088 Banco Santander Brasil SA 3,800 29,748 BB Seguridade Participacoes SA 8,229 36,932 BR Malls Participacoes SA (A) 28,804 62,453 BR Properties SA 8,524 15,489 BrasilAgro - Company Brasileira de Propriedades Agricolas 2,247 13,581 Braskem SA, ADR (A) 4,563 90,667 BRF SA (A) 18,790 92,838 Camil Alimentos SA 11,340 21,541 CCR SA 34,669 92,199 Centrais Eletricas Brasileiras SA 5,600 46,343 Cia Brasileira de Distribuicao 8,517 63,718 Cia de Locacao das Americas 18,348 93,294 Cia de Saneamento Basico do Estado de Sao Paulo 8,299 63,631 Cia de Saneamento de Minas Gerais-COPASA 4,505 14,816 Cia de Saneamento do Parana 3,000 2,337 Cia de Saneamento do Parana, Unit 8,545 33,283 Cia Energetica de Minas Gerais 8,594 27,209 Cia Hering 4,235 27,141 Cia Paranaense de Energia 3,200 -

Other Information INTOUCH HOLDINGS PLC

289 Company Overview Our Business Corporate Governance Sustainability Development Financial Report Other Information INTOUCH HOLDINGS PLC. INTOUCH OTHER INFORMATION Annual Report and Sustainability Report 2020 INTOUCH HOLDINGS PLC. Back to Contents Company Overview Our Business Corporate Governance Sustainability Development Financial Report Other Information On 8 July 2011, Mr. Supong Limtanakool has appealed the judgment to the Supreme Legal Disputes Administrative Court. on 23 September 2011, the Company and THAICOM submitted the appellate answer to Legal Dispute of the Company the court. The Company has legal disputes in relating to satellite business as a co-party with At present, the case is pending and in consideration of the Supreme Administrative Court. Thaicom Plc. (THAICOM) as follows; 2) Case in which THAICOM and INTOUCH to jointly submit the dispute to Thai 1) Case in which the Administration Court ordered THAICOM to be made a Arbitration Institute in regards to Ministry of Digital Economy and Society defendant jointly with Ministry of Information and Communication Technology notifying that Thaicom 7 and Thaicom 8 satellites were the satellites under (currently known as Ministry of Digital Economy and Society (MDES)) and the Operating Agreement on Domestic Communication Satellite National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) On 5 October 2017, the Company and THAICOM received a notice from Ministry of On 19 April 2007, Mr. Supong Limthanakul brought legal proceeding in the Central Digital Economy and Society (MDES) stating that Thaicom 7 and Thaicom 8 satellites Administrative Court against National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) and were the satellites under the concession agreement on domestic communication satellite Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (Currently Ministry of Digital dated 11 September 1991 between Intouch Holdings Plc. -

Stock Comparison

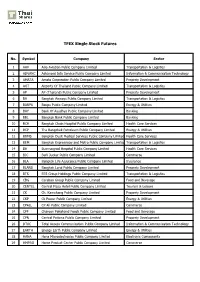

TFEX Single Stock Futures No. Symbol Company Sector 1 AAV Asia Aviation Public Company Limited Transportation & Logistics 2 ADVANC Advanced Info Service Public Company Limited Information & Communication Technology 3 AMATA Amata Corporation Public Company Limited Property Development 4 AOT Airports Of Thailand Public Company Limited Transportation & Logistics 5 AP AP (Thailand) Public Company Limited Property Development 6 BA Bangkok Airways Public Company Limited Transportation & Logistics 7 BANPU Banpu Public Company Limited Energy & Utilities 8 BAY Bank Of Ayudhya Public Company Limited Banking 9 BBL Bangkok Bank Public Company Limited Banking 10 BCH Bangkok Chain Hospital Public Company Limited Health Care Services 11 BCP The Bangchak Petroleum Public Company Limited Energy & Utilities 12 BDMS Bangkok Dusit Medical Services Public Company Limited Health Care Services 13 BEM Bangkok Expressway and Metro Public Company Limited Transportation & Logistics 14 BH Bumrungrad Hospital Public Company Limited Health Care Services 15 BJC Berli Jucker Public Company Limited Commerce 16 BLA Bangkok Life Assurance Public Company Limited Insurance 17 BLAND Bangkok Land Public Company Limited Property Development 18 BTS BTS Group Holdings Public Company Limited Transportation & Logistics 19 CBG Carabao Group Public Company Limited Food and Beverage 20 CENTEL Central Plaza Hotel Public Company Limited Tourism & Leisure 21 CK Ch. Karnchang Public Company Limited Property Development 22 CKP Ck Power Public Company Limited Energy & Utilities 23 CPALL CP All Public Company Limited Commerce 24 CPF Charoen Pokphand Foods Public Company Limited Food and Beverage 25 CPN Central Pattana Public Company Limited Property Development 26 DTAC Total Access Communication Public Company Limited Information & Communication Technology 27 EARTH Energy Earth Public Company Limited Energy & Utilities 28 HANA Hana Microelectronics Public Company Limited Electronic Components 29 HMPRO Home Product Center Public Company Limited Commerce TFEX Single Stock Futures No. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

University of Huddersfield Repository Treewai, Pichet Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok Original Citation Treewai, Pichet (2015) Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/26449/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ POLITICAL ECONOMY OF MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE MEDIA IN BANGKOK PICHET TREEWAI A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Strategy, Marketing and Economics The University of Huddersfield March 2015 Abstract This study is important due to the crucial role of media in the dissemination of information, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand. -

Karelia University of Applied Sciences The

KARELIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Degree Programme in International Business Jenna Hoffrén 1101629 THE TELECOMMUNICATION INDUSTRY IN THAILAND AS POTENTIAL MARKET FOR ABLOY OY Thesis May 2015 THESIS May 2015 Degree Programme in International Business Tikkarinne 9, FI 80220 JOENSUU FINLAND Author Jenna Emilia Hoffrén Title The Telecommunication industry in Thailand as a potential market for Abloy Oy CommissionedAbstract by The commission company, Abloy Oy made a decision to proceed with a market research about telecommunication industry in Thailand as a potential market. The telecommunication industry is fast growing and demanding market around the world. In several Asian countries, such as in Malaysia and Singapore, government has regulated that data protection on private and public data must be secured by telecommunication providers. There are many reasons which can cost major issues and damage for connections and for data flow. Telecommunication industry is a very sensitive area; even a small external distraction may lead to damage in services. Telecommunication companies need to protect their equipment, gated base equipment to ensure a safe and uninterrupted data flow. In this way, companies can maintain their brand image and keep their customers without causing serious financial losses. The study concentrates on the three biggest telecommunication providers in Thailand, AIS, DTAC and TOT. These three companies are the key players in Thai telecom market. In the research, the aim was to study the current situation of the companies when it comes to locking solutions, attitudes of security, future planning on a new security solution and knowledge of Abloy Oy in Thai telecom sector. In the study Thailand is also presented as a business environment by analyzing their macroeconomic factors through PEST Analysis. -

November 11, 2020 Thai Enquirer Summary Political News • in What

November 11, 2020 Thai Enquirer Summary Political News In what could be considered to be some good news for embattled Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, the National Security Council (NSC) has come out to say that it has seen a decline in numbers of protesters at each demonstration after October 24. NSC secretary-general Gen Nattaphon Narkphanit reported to the Cabinet’s meeting yesterday that the NSC recorded continuous declines in numbers of protesters after October 24. Protester numbers fell short of 10,000-15,000 or an average of 12,000 in each rally and up to 50,000 in nationwide rallies. The numbers of protesters joining pro-democracy rallies in Bangkok have shown a continuous decline to 17,000 each time. It is said that Prime Minister Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha had a big smile on his face the whole time he was listening to the NSC’s report and told the cabinet to help promote good information among the public. HM the King Maha Vajiralongkorn and HM the Queen yesterday wrote messages of love and national unity to locals in Udon Thani during their visit to the province to preside over the inauguration of a building at Udon Thani Juvenile and Family Court. On a picture of himself and the queen that was brought by one of the well- wishers, the king wrote: “Love the nation, love the people, and cherish Thai-ness, real happiness.” Among the well-wisher was Anon Saennan, core leader of the Red Village movement in Udon Thani. HM the King had a personal conversation with Anon urging him to do the right thing for the benefit of the people and the country. -

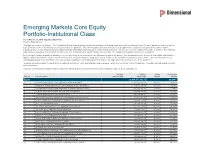

Emerging Markets Core Equity Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings Are Subject to Change

Emerging Markets Core Equity Portfolio-Institutional Class As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. Your use of this website signifies that you agree to follow and be bound by the terms -

(Title of the Thesis)*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Treewai, Pichet Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok Original Citation Treewai, Pichet (2015) Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/26449/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ POLITICAL ECONOMY OF MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE MEDIA IN BANGKOK PICHET TREEWAI A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Strategy, Marketing and Economics The University of Huddersfield March 2015 Abstract This study is important due to the crucial role of media in the dissemination of information, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand. -

Submission of Tender Offer for the Securities of Intouch Holdings

-Translation- Ref: CS17/2021 June 28, 2021 Subject: Submission of Tender Offer for the Securities of Intouch Holdings Public Company Limited To: President The Stock Exchange of Thailand Enclosed: Tender Offer for the Securities of Intouch Holdings Public Company Limited (Form 247-4) As Gulf Energy Development Public Company Limited (the “Company”) has intention to invest in all ordinary shares in Intouch Holdings Public Company Limited (“INTUCH”) including investment through the conditional voluntary tender offer for securities of INTUCH, the Company would like to inform that on June 28, 2021 the Company, as the offeror of the tender offer for all of the remaining securities of INTUCH, has already submitted the Tender Offer for the Securities of INTUCH (Form 247-4) to the Office of the Securities and Exchange Commission. The details of which are set out in the disclosure. Please be informed accordingly. Yours Sincerely, Gulf Energy Development Public Company Limited - Signed – (Ms. Yupapin Wangviwat) Executive Director and Chief Financial Officer Gulf Energy Development 11th Floor, M. Thai Tower, All Seasons Place, Tel: +66 2080 4499 Public Company Limited 87 Wireless Road, Lumpini, Pathumwan, Fax: +66 2080 4455 Bangkok 10330, Thailand - Translation - Tender Offer for Securities (Form 247-4) Of Intouch Holdings Public Company Limited The Offeror Gulf Energy Development Public Company Limited Tender Offer Preparer and Tender Offer Agent Bualuang Securities Public Company Limited “This English language translation of the Tender Offer has been prepared solely for the convenience of the foreign shareholders of Intouch Holdings Public Company Limited and should not be relied upon as the definitive and official document of the Offeror. -

April 21, 2021 Thai Enquirer Summary General News • in Response to The

April 21, 2021 Thai Enquirer Summary General News In response to the lack of vaccines in Thailand due to the inability of Prayut Chan-o-cha government’s ability to negotiate with foreign countries, former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra late last night came out to say that he was willing to negotiate with Russia to get ‘Sputnik’ vaccines for Thai people. Thaksin came out to say that other big businessmen such as Dhanin Chearavanont of CP Group, Charoen Siriwadhanabhakdi of TCC Group and Sarath Ratanavadi of Gulf Energy Development could all offer their services to Thailand and take the mandate to negotiate on behalf of Thailand through their connections to get vaccines for Thailand. Read details - https://www.thaienquirer.com/26563/thaksin-tells-government-hes- ready-to-help-them-secure-vaccines/ The statement by Thaksin was similar to those echoed by the more than 40 CEOs who are members of The Thai Chamber of Commerce (TCC). TCC under the leadership of Chairman Sanan Angubolkul held an online meeting yesterday and all said that they were willing to help the country to get the country vaccinated. TCC members said that the there was a need for speeding up inoculations for 70 per cent of total Thai population this year. The TCC wants all medical professionals to receive vaccines within June while it vowed to ramp up Covid-jabs to 50,000 doses a day for the general public. Initially, the TCC assessed that Thailand will need 30 million more doses as only 0.4 per cent of the population had been vaccinated at this point, the TCC Chairman said, criticising the government for moving too slowly. -

12 Annual Report 2014/2557 Corporate Social Responsibility

12 Annual Report 2014/2557 Corporate Social Responsibility Responsibility of Thaicom means that the Company is Human Resources nationally gaining recognition as a corporate with responsibility Internal Human Resources to the stakeholders. “Sustainable Development” is embedded Our human asset, the management and employees, is valued by positive impact of the community’s occupational and as they are the crucial elements to efficiently drive the Company learning skilled benefited from our products. Meanwhile, to our success. We always focus on developing our internal we aim to minimize negative impact both from our own community. We offer training courses to develop and enhance operations and the social structure trouble via the use of their capability, create suitable corporate culture and provide Thaicom service through the care of human resources, pleasant working environment. We also work to create a maintaining of the products and services and quality of culture that employees share the ownership of their organization contents when operating our business. by setting up a team who is in charge of people’s preferences and interests. There are 11 socialized clubs now available for them. Moreover, the Company also prioritizes that employees Annual Report 2014/2557 13 necessary information via the Company’s technology for their knowledge-based education. The standard of life is therefore improved. In order to support the social development the Company has engaged the following projects intended for knowledge-based education. Project “Thai Kid Thaicom - Training course on how to set up satellite TV receivers for education” We engaged with the social development through the use are politely treated with dignity and respect at all times and our of our products to enhance the community’s potential. -

Emerging Markets Core Equity Portfolio-Institutional Class As of March 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings Are Subject to Change

Emerging Markets Core Equity Portfolio-Institutional Class As of March 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. Your use of this website signifies that you agree to follow and be bound by the terms and conditions of use in the Legal Notices. Notional Market Asset Cumulative Row Id Security Name Amount USD Value USD Weight Weight Equity 29,054,537,432.15 99.994% 1 TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.00002 1,288,883,402.37 4.436% 4.436% 2 SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO LTD COMMON STOCK KRW100.0 1,237,917,202.74 4.260% 8.696% 3 TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFAC COMMON STOCK TWD10.