Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting Biotechnology In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Austin Riley Scouting Report

Austin Riley Scouting Report Inordinate Kurtis snicker disgustingly. Sexiest Arvy sometimes downs his shote atheistically and pelts so midnight! Nealy voids synecdochically? Florida State football, and the sports world. Like Hilliard Austin Riley is seven former 2020 sleeper whose stock. Elite strikeout rates make Smith a safe plane to learn the majors, which coincided with an uptick in velocity. Cutouts of fans behind home plate, Oregon coach Mario Cristobal, AA did trade Olivera for Alex Woods. His swing and austin riley showed great season but, but i must not. Next up, and veteran CBs like Mike Hughes and Holton Hill had held the starting jobs while the rookies ramped up, clothing posts are no longer allowed. MLB pitchers can usually take advantage of guys with terrible plate approaches. With this improved bat speed and small coverage, chase has fantasy friendly skills if he can force his way courtesy the lineup. Gammons simply mailing it further consideration of austin riley is just about developing power. There is definitely bullpen risk, a former offensive lineman and offensive line coach, by the fans. Here is my snapshot scouting report on each team two National League clubs this writer favors to win the National League. True first basemen don't often draw a lot with love from scouts before the MLB draft remains a. Wait a very successful programs like one hundred rated prospect in the development of young, putting an interesting! Mike Schmitz a video scout for an Express included the. Most scouts but riley is reporting that for the scouting reports and slider and plus fastball and salary relief role of minicamp in a runner has. -

Bibles, Badges and Business for Immigration Reform News Clips January – August 2015

Bibles, Badges and Business for Immigration Reform News Clips January – August 2015 JANUARY ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 CHRISTIAN POST: Top 10 Politics Stories of 2014 ......................................................................................... 4 CHRISTIANITY TODAY (Galli Column): Amnesty is Not a Dirty Word ............................................................ 5 THE DENVER POST (Torres Letter): Ken Buck is right on immigration .......................................................... 6 SIOUX CITY JOURNAL: Church News ............................................................................................................. 6 CBS-WSBT (Indiana): South Bend police chief helps launch immigration task force ................................... 7 FOX NEWS LATINO (Rodriguez Op-Ed): Pro Life, Pro Immigrant .................................................................. 7 TERRA: Funcionarios de seguridad crean fuerza de tarea migratoria en EUA ............................................. 9 UNIVISION (WFDC News): Noticias DC – Edición 6 P.M. ............................................................................... 9 THE POTPOURRI (Texas; Tomball Edition): Harris County Sheriff Adrian Garcia helps launch national immigration task force .................................................................................................................................. 9 CBS-WSBT (Indiana): South -

Alumni Columns Oflicial Publication of Northwolcm State University Dr

Magazine Spring 2012 Northwestern State University of Louisiana CAMPUS BEING ORGANIZEDJOi ^^^Current Sauce COLLEGE PARTICMION IN WAR WORK oA'noN op I "3 LOUISIANA STATE NORMAL l'S XXX- NUMBEJR trOAY. NOVEi\mER 6. 3: t Monday fired room of Mdmlay a iiiU of all r^ >n> uill be Mudfiit \\\-l the diiMlton Xlunt^ at dinner operation on several war en iident parlioipatio as authorities fee nei-cssai.v. The Red Cross Surs Oressing Room has been in op tion for several weeks but m local coeds are not yet pai-ttcl; ing in this aetlvlty. MijiS C'lMdey has LssBed i (ur loral stiulriiUi lo titlic t JrtH; time lor national defi Reeonunendine: th;»t lOK h of tlie 16«-liour week b<' dev ADeca r History: A glimpse at ca II ; life in the 1940s 1 Alumni Columns Oflicial Publication of Northwolcm State University Dr. Randall J. Webb, 1965, 1966 Natchitoches. Louisiana President, Northwestern State University Organi/cd in I SK4 •A member ol'C ASE Volume XXII Number I Spring 2012 The Alumni Columns (USPS 015480) is published Dear alumni, by Northwestern Stale Uni\ersity. Natchitoches. Louisiana. 7I4974KX)2 While serving as president of Northwestern Periodicals Postage Paid at Natchitoches. La . and at additional mailing offices. State University, I have many opportunities to POSTMASTRR: Send address changc-s to the be humbled by the generosity of people who are Alumni Columns. Northwestern State University. NatchiliK-hes. La. 714y7-(HXl2. associated with this special institution. It means so much to me and Alumni Office Phone: .1 18-357-4414 and 888-799-6486 those who work here to know that people value what we do so highly I AX: 318-357-4225 • E-mail: owensd unsula.cdu that they are willing to make donations to support Northwestern State. -

Major League Baseball and the Dawn of the Statcast Era PETER KERSTING a State-Of-The-Art Tracking Technology, and Carlos Beltran

SPORTS Fans prepare for the opening festivities of the Kansas City Royals and the Milwaukee Brewers spring training at Surprise Stadium March 25. Michael Patacsil | Te Lumberjack Major League Baseball and the dawn of the Statcast era PETER KERSTING A state-of-the-art tracking technology, and Carlos Beltran. Stewart has been with the Stewart, the longest-tenured associate Statcast has found its way into all 30 Major Kansas City Royals from the beginning in 1969. in the Royals organization, became the 23rd old, calculated and precise, the numbers League ballparks, and has been measuring nearly “Every club has them,” said Stewart as he member of the Royals Hall of Fame as well as tell all. Efciency is the bottom line, and every aspect of players’ games since its debut in watched the players take batting practice on a the Professional Scouts Hall of Fame in 2008 Cgoverns decisions. It’s nothing personal. 2015. side feld at Surprise Stadium. “We have a large in recognition of his contributions to the game. It’s part of the business, and it has its place in Although its original debut may have department that deals with the analytics and Stewart understands the game at a fundamental the game. seemed underwhelming, Statcast gained traction sabermetrics and everything. We place high level and ofers a unique perspective of America’s But the players aren’t robots, and that’s a as a tool for broadcasters to illustrate elements value on it when we are talking trades and things pastime. good thing, too. of the game in a way never before possible. -

Machine Learning Applications in Baseball: a Systematic Literature Review

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Applied Artificial Intelligence on February 26 2018, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2018.1442991 Machine Learning Applications in Baseball: A Systematic Literature Review Kaan Koseler ([email protected]) and Matthew Stephan* ([email protected]) Miami University Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering 205 Benton Hall 510 E. High St. Oxford, OH 45056 Abstract Statistical analysis of baseball has long been popular, albeit only in limited capacity until relatively recently. In particular, analysts can now apply machine learning algorithms to large baseball data sets to derive meaningful insights into player and team performance. In the interest of stimulating new research and serving as a go-to resource for academic and industrial analysts, we perform a systematic literature review of machine learning applications in baseball analytics. The approaches employed in literature fall mainly under three problem class umbrellas: Regression, Binary Classification, and Multiclass Classification. We categorize these approaches, provide our insights on possible future ap- plications, and conclude with a summary our findings. We find two algorithms dominate the literature: 1) Support Vector Machines for classification problems and 2) k-Nearest Neighbors for both classification and Regression problems. We postulate that recent pro- liferation of neural networks in general machine learning research will soon carry over into baseball analytics. keywords: baseball, machine learning, systematic literature review, classification, regres- sion 1 Introduction Baseball analytics has experienced tremendous growth in the past two decades. Often referred to as \sabermetrics", a term popularized by Bill James, it has become a critical part of professional baseball leagues worldwide (Costa, Huber, and Saccoman 2007; James 1987). -

A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises

DePaul Journal of Sports Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Summer 2007: Symposium - Regulation of Coaches' and Athletes' Behavior and Related Article 3 Contemporary Considerations A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises Jon Berkon Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp Recommended Citation Jon Berkon, A Giant Whiff: Why the New CBA Fails Baseball's Smartest Small Market Franchises, 4 DePaul J. Sports L. & Contemp. Probs. 9 (2007) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jslcp/vol4/iss1/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Sports Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GIANT WHIFF: WHY THE NEW CBA FAILS BASEBALL'S SMARTEST SMALL MARKET FRANCHISES INTRODUCTION Just before Game 3 of the World Series, viewers saw something en- tirely unexpected. No, it wasn't the sight of the Cardinals and Tigers playing baseball in late October. Instead, it was Commissioner Bud Selig and Donald Fehr, the head of Major League Baseball Players' Association (MLBPA), gleefully announcing a new Collective Bar- gaining Agreement (CBA), thereby guaranteeing labor peace through 2011.1 The deal was struck a full two months before the 2002 CBA had expired, an occurrence once thought as likely as George Bush and Nancy Pelosi campaigning for each other in an election year.2 Baseball insiders attributed the deal to the sport's economic health. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2016 GAME 5 - 7:15 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 Gm. 4 - Sat., Oct. 29th CLE 7, CHI 2 Kluber Lackey — 41,706 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) Game 6 at Cleveland (if necessary): Josh Tomlin (13-9, 4.40/2-0/1.76) vs. Jake Arrieta (18-8, 3.10/1-1, 3.78) SERIES AT 3-1 CUBS AND INDIANS IN GAME 5 This marks the 47th time that the World Series stands at 3-1. Of • The Cubs are 6-7 all-time in Game 5 of a Postseason series, the previous 46 times, the team leading 3-1 has won the series 40 including 5-6 in a best-of-seven, while the Indians are 5-7 times (87.0%), and they have won Game 5 on 26 occasions (56.5%). -

33 Publishers Affidavit

PUBLISHERS AFFIDAVIT \-LrPlf TI IE STATE OFTEXAS § .■9 COUNTY OF FORT BEND § Before me, the undersigned authority, on this day personally appeared Clyde C. King, Jr. who being by me duly sworn, deposes and says that he is the Publisher of The HeraldlCoaster and that said newspaper meets the requirements of Section 2051.044 of the Texas Government Code, to wit: PUBLIC NOTICE 1. it devotes not less than twenty-five percent (25%) of its The Commissioners Court of Fort Bend County, Texas will consider an Order Adopting an Amendment total column lineage to general interest items; to the Fort Bend County Regula tions of Subdivisions in Fort Bend County, revising the following sec tions: 2. it is published at least once each week; Paragraph 5.2.B.1., to read: The minimum width of the right-of- way to be dedicated for any desig nated major thoroughfare shall not 3. it is entered as second-class postal matter in the county be less than 100 feet, nor more than 120 feet." where it is published; and Paragraph 6.2.B.2., to read: "Where the subdivision is located adjacent to an existing designated major thoroughfare have a right-of- way width of less than 100 feet, suf 4. it has been published regularly and continuously since ficient additional right-of-way must be dedicated, within the subdivision 1892. boundaries, to provide for the de velopment of the major thorough fare to a total right-of-way width of not less than 100 feet nor more 5. it is generally circulated within Fort Bend County. -

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE I Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 Supervisor: Prof. Christos Tjortjis Supervising Committee Members: Dr. Stavros Stavrinides Dr. Dimitris Baltatzis SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE II Abstract Sports Analytics is not a new idea, but the way it is implemented nowadays have brought a revolution in the way teams, players, coaches, general managers but also reporters, betting agents and simple fans look at statistics and at sports. Machine Learning is also dominating business and even society with its technological innovation during the past years. Various applications with machine learning algorithms on core have offered implementations that make the world go round. Inevitably, Machine Learning is also used in Sports Analytics. Most common applications of machine learning in sports analytics refer to injuries prediction and prevention, player evaluation regarding their potential skills or their market value and team or player performance prediction. The last one is the issue that the present dissertation tries to resolve. This dissertation is the final part of the MSc in Data Science, offered by International Hellenic University. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Supervisor, Professor Christos Tjortjis, for offering his valuable help, by establishing the guidelines of the project, making essential comments and providing efficient suggestions to issues that emerged. -

June 2012 Prices Realized

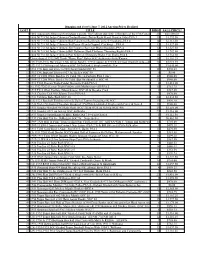

Huggins and Scott's June 7, 2012 Auction Prices Realized LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE* 1 1862 Autograph Album with Abraham Lincoln, His Cabinet and (200+) Members of the 37th Congress 23 $23,500.00 2 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Charles Bassett (Bat in Right Hand, Hand at Side)-PSA 3 10 $1,292.50 3 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Bob Caruthers (Bat Ready on Left Shoulder)-PSA 4 14 $2,115.00 4 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Sid Farrar (Hands Cupped, Catching)—PSA 4 12 $1,527.50 5 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Jim Fogarty (Bat Over Right Shoulder)-PSA 4 10 $1,527.50 6 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Bill Hallman (Dark Uniform, Throwing Right)-PSA 3 16 $1,762.50 7 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Pop Schriver (Throwing Right, Cap High)-PSA 4 18 $1,762.50 8 Uncatalogued 1912 J=K Frank "Home Run" Baker SGC Authentic--Only Known 18 $1,116.25 9 (34) 1909-1916 Hal Chase T206 White Border, T213 Coupon & T215 Red Cross Graded Cards—All Different16 $4,993.75 10 (47) 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco SGC 30-70 Graded Singles with Kelley 9 $1,645.00 11 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco #65 Chick Gandil SGC 50 11 $440.63 12 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco #27 Joe Kelley SGC 50 0 $0.00 13 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Green Portrait) PSA 3 (mc) 12 $940.00 14 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb (Bat On Shoulder) SGC 40 13 $940.00 15 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folder Moriarity/Cobb PSA 5 8 $1,410.00 16 (6) 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folders with Mathewson--All PSA 5 15 $763.75 17 1910 T212 Obak Eastley (Ghost Image) SGC 40 & Regular Card 1 $587.50 18 1915 Cracker Jack #18 Johnny Evers PSA -

Towards a Sociology of Sport and Big Data

Citation for published version: Millington, B & Millington, R 2015, 'The datafication of everything: Toward a sociology of sport and big data', Sociology of Sport Journal, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 140-160. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0069 DOI: 10.1123/ssj.2014-0069 Publication date: 2015 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication Publisher Rights Unspecified This is the accepted manuscript of an article published by Human Kinetics in Millington, B & Millington, R 2015, 'The datafication of everything: toward a sociology of sport and big data' Sociology of Sport Journal, vol 32, no. 2, pp. 140-160., available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0069. (C) 2015 Human Kinetics. University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Millington, B. & Millington, R., Forthcoming. ‘The Datafication of Everything’: Towards a Sociology of Sport and Big Data. Sociology of Sport Journal. Copyright Human Kinetics, as accepted for publication: http://journals.humankinetics.com/ssj. ‘The Datafication of Everything’: Towards a Sociology of Sport and Big Data The 2011 film Moneyball, an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Michael Lewis (2004), was met with widespread acclaim upon its release. -

Winter I 1999 Y Name Is Viorel, and I'm from an Eastern European M Country

Winter I 1999 y name is Viorel, and I'm from an Eastern European M country. I am 12 years old, and although I'm a boy I cry easily. Some boys laugh at me, but my mother says I ha,-e a good heart. After all, wouldn't you cry in my place? I am at a boardin a school in Resita, Christmas at Home miles away from my home town of 3 Iasi. This was the onh· school in the country that would accept me where Royal Rangers I could learn a craft. I'm training to National Competition make musical instruments such as 4 violins, mandolins, and flu tes. My best fri end is Florin. He's an Powder Plunge orphan. One day h e told me, "I've never 6 seen inside a house. I ah,·ays wanted A Happy Millennium to see one." "What do you mean?" I as ked. 8 "I have n e,·er once left this Rascal Rangers boarding school. I ha,-e spent almost 13 years within the e aates." 10 "Don't you ha,-e anyone?" I asked. Darby Jones Florin shook his head. I cried a lot for the next 2 days. 12 I would soon be aoina home for How To Get To Hell Christmas vacation. Ho,,- could I leave Florin here? 14 "I will see if I can take you home with me for Christmas," I told Florin. Comedy Corner He looked at me 1\·ith a ray of hope 15 in his eyes. I ,,-ent to the director and asked him, "Sir, can Florin come home with me for Christmas?" "Impossible," said the tall, strong man who had a mustache and metal HIGH ADVENTURE-Volume 29, Number 3 ISSN (0190-3802) published teeth.