Visionary-Urban-Africa.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 18:33 Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Résumé de l'article Volume 21, numéro 2, 2011 Cet article livre des réflexions générales sur quelques défis auxquels les compositeurs africains de musique de concert sont confrontés. Le point de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar départ spécifique se trouve dans une anthologie qui date de 2009, Piano Music DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar of Africa and the African Diaspora, rassemblée par le pianiste et chercheur ghanéen William Chapman Nyaho et publiée par Oxford University Press. Aller au sommaire du numéro L’anthologie offre une grande panoplie de réalisations artistiques dans un genre qui est moins associé à l’Afrique que la musique « populaire » urbaine ou la musique « traditionnelle » d’origine précoloniale. En notant les avantages méthodologiques d’une approche qui se base sur des compositions Éditeur(s) individuelles plutôt que sur l’ethnographie, l’auteur note l’importance des Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal rencontres de Steve Reich et György Ligeti avec des répertoires africains divers. Puis, se penchant sur un choix de pièces tirées de l’anthologie, l’article rend compte de l’héritage multiple du compositeur africain et la façon dont cet ISSN héritage influence ses choix de sons, rythmes et phraséologie. Des extraits 1183-1693 (imprimé) d’oeuvres de Nketia, Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi et Osman servent d’illustrations à cet 1488-9692 (numérique) article. Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Agawu, K. -

Afro Modern: Journeys Through the Black Atlantic Tate Liverpool Educators’ Pack Introduction

Afro Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic Tate Liverpool Educators’ Pack Introduction Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Verso: London, 1993) identifies a hybrid culture that connects the continents of Africa, the Americas and Europe. Inspired by Gilroy’s seminal book, this major exhibition at Tate Liverpool examines the impact of Black Atlantic culture on modernism and the role of black artists and writers from the beginning of the twentieth-century to present day. Divided into seven chronological chapters, the exhibition takes as its starting point the influences of African sculpture on artists such as Picasso and Brancusi in the evolution of Cubism and Abstract art. The journey continues across the Atlantic tracking the impact of European modernism on emerging African- American Artists, such as the Harlem Renaissance group. It traces the emergence of modernism in Latin America and Africa and returns to Europe at the height of the jazz age and the craze for “Negrophilia”. It follows the transatlantic commuting of artists between continents and maps out the visual and cultural hybridity that has arisen in contemporary art made by people of African descent. The final section examines current debates around “Post-Black Art” with contemporary artists such as Chris Ofili and Kara Walker. This pack is designed to support educators in the planning, execution and following up to a visit to Tate Liverpool. It is intended as an introduction to the exhibition with a collection of ideas, workshops and points for discussion. The activities are suitable for all ages and can be adapted to your needs. -

Lost Wax: an Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2009 Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art Practice Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Kevin, "Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal" (2009). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 735. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/735 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Bell, Kevin Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Advisor: Diop, Issa University of Denver International Studies Africa, Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal Arts and Culture, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2009 Table of Contents ABSTRACT: ................................................................................................................................................................1 I. LEARNING GOALS: .........................................................................................................................................2 I. RESOURCES AND METHODS: ......................................................................................................................3 -

Global Heritage Assemblages and Modern Architecture in Africa

Rescuing Modernity: Global Heritage Assemblages and Modern Architecture in Africa Citation for published version (APA): Rausch, C. (2013). Rescuing Modernity: Global Heritage Assemblages and Modern Architecture in Africa. Universitaire Pers Maastricht. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20131018cr Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2013 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20131018cr Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Five Takes on African Art a Study Guide

FIVE TAKES ON AFRICAN ART A STUDY GUIDE TAKE 1 considers materiality, and the elements used to make aesthetic objects. It also considers the connections that materials have to the people who originally crafted them, and furthermore, their ties to new generations of crafters, interpreters, and collectors of African works. The objects in this collection challenge our notions of “African art” in that they were not formed for purely aesthetic purposes, but rather were created from raw, natural materials, carefully refined, and then skillfully handcrafted to serve particular needs in homes and communities. It is fascinating to consider that each object featured here bears a characteristic that identifies it as belonging to a distinct region or group of people, and yet is nearly impossible to unearth the narratives of the individual artists who created them. Through these works, we can consider the bridge between materiality and diaspora—objects of significance with “genetic codes” that move from one hand to the next, across borders, and oceans, with a dynamism that is defined by our ever-shifting world. Here, these “useful” objects take on a new function, as individual parts to an entire chorus of voices—each possessing a unique story in its creation and journey. What makes these objects ‘collectors’ items’? Pay close attention to the shapes, forms, and craftsmanship. Can you find common traits or themes? The curator talks about their ‘genetic codes’. Beside the object’s substance, specific to the location of its creation, it may carry traces of other accumulated materials, such as food, skin, fiber, or fluids. -

Kubatana – When African Art Illuminates Norway

Latest: Tickle Your Taste Buds with Africa’s Culinary Wealth Africa, The home of the Black Panther The African free-trade zone comes into effect Ghana robotic team wins World Robofest Championship Kubatana – when African art illuminates Norway $ BUSINESS ∠ ECONOMY ∠ LIFESTYLE ∠ MUSIC ∠ SPORT MOVIES VIDEOS LOG IN OTHER ∠ FRANÇAIS & Culture Inspirations Kubatana – when African art illuminates Norway ! July 21, 2019 " Christelle Kamanan # African artists, Art, contemporary art, exhibition Recommend Like Share Tweet ubatana or friendliness in Shona language (Zimbabwe). This exhibition highlights the work of 33 African artists in a warm and aesthetic way. All works are visible until 21 September 2019 at the K Kunstlabotorium in Vestfossen, Norway. Yassine Balbzioui – photo C.K. Gonçalo Mabunda – photo C.K. Aboudia – photo C.K. Serge Attukwei Clottey – photo C.K. Kubatana, showcase of African contemporary art English speaking Africa African contemporary art; what does it look like? The monumental installation of the Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey announces the color, even before entering the Kunstlaboratorium. Starting from his origins, his family history related to the sea and the migration, he made a work of several meters. Like a marine net, the installation covers a large part of the front façade of the building. All these small tiles, made from water can, are in the image of contemporary African art: colorful, flamboyant and imposing. Francophone Africa & Arabic There is also the imposing 10-meter mural by Yassine Balbzioui (Morocco). You feel very small near such an achievement; as against the immensity of the possibilities of art. Aboudia (Ivory Coast) surprises and questions with a painting of human relations in our time. -

Contemporary Africa Arts

CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ARTS MAPPING PERCEPTIONS, INSIGHTS AND UK-AFRICA COLLABORATIONS 2 CONTENTS 1. Key Findings 4 2. Foreword 6 3. Introduction 8 4. Acknowledgements 11 5. Methodology 12 6. What is contemporary African arts and culture? 14 7. How do UK audiences engage? 16 8. Essay: Old Routes, New Pathways 22 9. Case Studies: Africa Writes & Film Africa 25 10. Mapping Festivals - Africa 28 11. Mapping Festivals - UK 30 12. Essay: Contemporary Festivals in Senegal 32 13. What makes a successful collaboration? 38 14. Programming Best Practice 40 15. Essay: How to Water a Concrete Rose 42 16. Interviews 48 17. Resources 99 Cover: Africa Nouveau - Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: Wanjira Gateri. This page: Nyege Nyege Festival - Jinja, Uganda. Credit: Papashotit, commissioned by East Africa Arts. 3 1/ KEY FINDINGS We conducted surveys to find out about people’s perceptions and knowledge of contemporary African arts and culture, how they currently engage and what prevents them from engaging. The first poll was conducted by YouGov through their daily online Omnibus survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,000 adults. The second (referred to as Audience Poll) was conducted by us through an online campaign and included 308 adults, mostly London-based and from the African diaspora. The general British public has limited knowledge and awareness of contemporary African arts and culture. Evidence from YouGov & Audience Polls Conclusions Only 13% of YouGov respondents and 60% of There is a huge opportunity to programme a much Audience respondents could name a specific wider range of contemporary African arts and example of contemporary African arts and culture, culture in the UK, deepening the British public’s which aligned with the stated definition. -

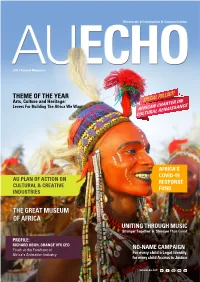

Au Echo 2021 1 Note from the Editor

Directorate of Information & Communication 2021 Annual Magazine THEME OF THE YEAR Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers For Building The Africa We Want AFRICAN CHARTER ON CULTURAL RENAISSANCE AFRICA’S COVID-19 AU PLAN OF ACTION ON RESPONSE CULTURAL & CREATIVE FUND INDUSTRIES THE GREAT MUSEUM OF AFRICA UNITING THROUGH MUSIC ‘Stronger Together’ & ‘Stronger Than Covid’ PROFILE: RICHARD OBOH, ORANGE VFX CEO Youth at the Forefront of NO-NAME CAMPAIGN Africa’s Animation Industry For every child a Legal Identity, for every child Access to Justice www.au.int AU ECHO 2021 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR he culture and creative industries (CCIs) generate annual global revenues of up to US$2,250 billion dollars and Texports in excess of US$250 billion. This sector currently provides nearly 30 million jobs worldwide and employs more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector and contributes LESLIE RICHER up to 10% of GDP in some countries. DIRECTOR Directorate of Information & In Africa, CCIs are driving the new economy as young Africans Communication tap into their unlimited natural resource and their creativity, to create employment and generate revenue in sectors traditionally perceived as “not stable” employment options. taking charge of their destiny and supporting the initiatives to From film, theatre, music, gaming, fashion, literature and art, find African solutions for African issues. On Africa Day (25th the creative economy is gradually gaining importance as a May), the African Union in partnership with Trace TV and All sector that must be taken seriously and which at a policy level, Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) organised a Virtual Solidarity decisions must be made to invest in, nurture, protect and grow Concert under the theme ‘Stronger Together’ and ‘Stronger the sectors. -

OCPA NEWS No174

Observatory of Cultural Policies in Africa The Observatory is a Pan African international non-governmental organization. It was created in 2002 with the support of African Union, the Ford Foundation and UNESCO with a view to monitor cultural trends and national cultural policies in the region and to enhance their integration in human development strategies through advocacy, information, research, capacity building, networking, co-ordination and co-operation at the regional and international levels. OCPA NEWS No174 O C P A 12 February 2007 This issue is sent to 8485 addresses * VISIT THE OCPA WEB SITE http://www.ocpanet.org * 1 Are you planning meetings, research activities, publications of interest for the Observatory of Cultural Policies in Africa? Have you heard about such activities organized by others? Do you have information about innovative projects in cultural policy and cultural development in Africa? Do you know interesting links or e-mail address lists to be included in the web site or the listserv? Please send information and documents for inclusion in the OCPA web site! * Thank you for your co-operation. Merci de votre coopération. Máté Kovács, editor: [email protected] *** New Address: OCPA Secretariat 725, Avenida da Base N'Tchinga, Maputo, Mozambique Postal address; P. O. Box 1207 E-mail: [email protected] or Lupwishi Mbuyamba, director: [email protected] *** You can subscribe to OCPA News via the online form at http://ocpa.irmo.hr/activities/newsletter/index-en.html. Vous pouvez vous abonner ou désabonner à OCPA News, via le formulaire disponible à http://ocpa.irmo.hr/activities/newsletter/index-fr.html * Previous issues of OCPA News are available at Lire les numéros précédents d’OCPA News sur le site http://www.ocpanet.org/ 2 ××× In this issue – Dans ce numéro A. -

Pan-Africanism and the Black Festivals of Arts and Culture: Today’S Realities and Expectations

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 3, Ver. 1 (Mar. 2015), PP 22-28 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Pan-Africanism and the Black Festivals of Arts and Culture: Today’s Realities and Expectations Babasehinde Augustine Ademuleya (Ph. D) & Michael Olusegun Fajuyigbe (M. Phil) Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Obáfémi Awólówò University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria . Abstract: The first two editions of the Festivals of Blacks arts and culture which owed much to the ideologies of the Pan-Africanism and Negritude that preceded them, no doubt laid legacies that have continued to serve as strong reference points in the discussion of Africans and African descent relationship. Apart from providing an unusual forum that brought to light the diverse contributions of Blacks and African peoples to the universal currents of thought and arts, both editions drew attentions to the expected relationship between the continental Africans and their offspring in the Diaspora. The events reassert the African identity thus creating the platform for continental Africa and the Diaspora to move through the borders of nation state and the psychosocial borders of racism which is central to all Pan-Africanist freedom movements. It is however worrisome that forty eight years after the maiden edition of the festival (FESMAN) and thirty seven years after the second (FESTAC), the achieved cultural integration is yet to translate into much expected economical, political, educational, philosophical and technological advancements of African nations and that of the Diaspora. This paper therefore attempts a review of the Black Festivals of Arts with a view to highlighting how the achieved cultural integration through the arts could be further explored for today’s realities and expectations. -

Salah M. Hassan African Modernism

Salah M. Hassan African Modernism: Beyond Alternative Modernities Discourse African Modernism and Art History’s Exclusionary Narrative On October 25, 2002, South African artist Ernest Mancoba, a pillar of modern African art, passed away in a hospital in Clamart, a suburb of Paris. He was ninety- eight. With a life that spanned most of the twentieth century, Mancoba had lived through the high periods of modern- ism and postmodernism. A few months before Mancoba’s passing, I was extremely fortunate to have received an extended interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist, submitted for publication to Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, which I edit. The interview was eventually published in 2003 and was indeed one of the most inspiring texts that I have read in years.1 However, why should Mancoba’s life and his artistic accomplishments be instructive in exploring African modernity and modernism? To be sure, it is not the mere coincidence of his thinking about European modernism or the sig- nificance of Europe, where Mancoba lived and worked for more than fifty years. Mancoba is memorable for his remarkable life of creativity, for his intellectual vigor, for his unique and pro- South Atlantic Quarterly 109:3, Summer 2010 DOI 10.1215/00382876- 2010- 001 © 2010 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/south-atlantic-quarterly/article-pdf/109/3/451/470354/SAQ109-03-01HassanFpp.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 452 Salah M. Hassan found body of work, and for his innovative visual vocabulary and style that have come to shape an important part of our understanding of African modernism in the visual arts. -

N'vest-Ing in the People: the Art of Jae Jarrell

Jae Jarrell N’Vest-ing in the People: The Art of Jae Jarrell by D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem 1977 dawned on a Nigeria brimming with AFRICOBRA (African Commune of promise, full with the spoils of Niger Bad Relevant Artists)—the Delta oil and national pride 17 years legendary collective established in post-independence. It was a time of 1968 on Chicago’s south side with afrobeat musical innovation, of the goal to uplift and celebrate cross-continental exchange, of Black community, culture, and vibrancy and possibility. A contin- self-determination.1 Jae describes gent of 250 artists and cultural the journey as a “traveling party,” a producers selected by artist Jeff veritable who’s who of famous Donaldson and the U.S. organizing Black artists, and recalls thinking, committee, traveled from New York “If the afterlife is like this, then to Lagos, Nigeria, on two planes that’ll be alright!” 2 chartered by the U.S. Department of Foreign Affairs, to participate in Imagine the moment. The outline of FESTAC ’77, the Second World West Africa appears on the distant Black and African Festival of Arts horizon. Excitement mounts as the and Culture. Among them were Jae densely inhabited shorelines and and Wadsworth Jarrell, two of sprawling metropolis of Lagos Donaldson’s fellow co-founders of (pronounced “ley” “goss”) come into view, and even in the air condi- co-founder and curator Gerald Arts6 held in Dakar, Senegal in singer and civil rights activist tioned plane, you can feel the trop- Williams reflected on the cultural 1966 hosted by visionary President Miriam Makeba lovingly known as ical rays as the plane inches closer and creative impact of partici- Léopold Sédar Senghor, FESTAC “Mama Africa,” the awe-inspiring to landing.