Illinois University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Director's Report

#EBD 12.35 ALA Executive Director’s Report to ALA Executive Board Prepared by Tracie D. Hall April 5, 2021 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ASSOCIATION UPDATES AND HIGHLIGHTS • ALA Leads Charge on Library Inclusion in American Rescue Plan Act • Membership Committee and Member Relationship Services Propose Membership Retention Strategy • ASGCLA Transition Update • National Library Week • First Widescale Study of Race and LIS workforce Retention • Select Division Events this Quarter • Human Resources/Staffing Update • Financial Update • Pivot Strategy Update • Draft Cross Functional Teams REPORTS OF ALA OFFICES AND UNITS • Chapter Relations Office • Communications And Marketing Office • Conference Services • Development • Governance Office • Information Technology (IT) • International Relations Office • Member Relations & Services • Office for Accreditation • Office for Diversity, Literacy And Outreach Services • Office for Intellectual Freedom • Public Policy and Advocacy • Public Programs Office • Publishing REPORT OF ALA DIVISIONS • American Association of School Librarians • Association of College And Research Libraries • Association For Library Service to Children • Core • Public Library Association • Reference And User Services Association • United for Libraries • Young Adult Library Services Association ASSOCIATION UPDATE The third quarter of FY21 finds the American Library Association busy launching key new programs designed to support libraries nationally that have been adversely impacted by reductions in funding even as their communities turn to them for increasingly urgent information access and digital connectivity needs; and unveiling new initiatives to ensure that the library workers who run them have expanded access to the educational resources, practitioner networks, data and tends analysis, and opportunities to apply for grants and individual financial support needed to ensure that their libraries and careers remain productive and impactful. -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

Saturday Issue 2 V2.Indd

Issue 2 ������������Seattle, WA Saturday, January 20, 2007 Highlights Klein to Present Curley SATURDAY Memorial Lecture oe Klein, senior writer for Seattle Sunrise Time magazine and au- Speaker Series Jthor of several best selling Transforming Yourself: books, will discuss “Islam, Iraq and the War on Terror” at the Reaching New Heights Eighth Annual Arthur Curley 8:00 - 9:00 a.m. Memorial Lecture today at 4:00 Washington State p.m. in the Washington State Convention and Trade Trade and Convention Center, Center, Room 6B/C Room 611-614. Klein’s provocative weekly column, “In the Arena,” covers Council Orientation national and international af- 8:00-10:00 a.m. fairs. He has written lengthy Sheraton Hotel portraits of Barack Obama, Metropolitan A John McCain and Tony Blair, to name a few. In 2004, Klein won ALA President Leslie Burger, right, and President-Elect Loriene Joe Klein Roy, left, cut the ribbon to open the exhibits as the ALA Board Presidential Candidates the National Headliner Award for best magazine column. Continued on page 4 looks on. Forum 11:00 am-12:00 p.m. Washington State Tracie D. Hall to Keynote Convention and Trade Center, Room 6B/6C King Celebration racie D. Hall, and the Black Caucus of the American ALA/FOLUSA Adult recently appointed Assis- Library Association (BCALA), Literature Spotlight Ttant Dean of the GLSIS the Association’s seventh an- 2:00-4:00 p.m. at Dominican University will nual sunrise celebration will be the keynote speaker at the honor the work and life of Dr. Washington State Dr. -

Open to All: Serving the GLBT Community in Your Library

OPEN TO ServingA the GLBT LCommunity inL Your Library A Toolkit from the American Library Association Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Round Table Introduction This Toolkit is designed to help library staff • Public libraries are committed to serving and better understand gay, lesbian, bisexual and representing their entire community including transgender (GLBT) library users, how to best GLBT library users whether or not they are “out.” serve their needs, and how to manage challenges • School libraries are particularly important; that often arise. teenagers question their sexuality and identity and need a welcoming place; children and Acceptance of GLBT people in mainstream teens need to see themselves represented in American society has been steadily growing. books at school as well as at the public library. However, library materials, programs, and • Academic libraries should not only provide displays related to sexual orientation and access to collections and academic support, gender identity still cause controversy. The fear but also welcoming spaces. of a challenge may cause some librarians to be deterred from buying materials or including In any community, there are GLBT persons who services for GLBT people in their service profile; are not ready to be recognized as such, and failing to provide these resources in ways that it’s important to avoid assumptions and act can be easily used by vulnerable populations are with respect. People who are “in the closet” or forms of censorship and discrimination. questioning often need information resources the most, so it is essential to provide safe and Every community has a GLBT population and anonymous access, without judgment. -

Summer Reading Book Lists

BPL Teen Summer Reading Best of the Best List If you’re not sure what to read, check out the books on this list. The list includes some of the best books published over the last few years. Read one of these books to check off a space on your summer reading bingo sheet or earn five bonus points on your reading log. You might even find a new favorite author. The Buckeye Teen Book Award is an award entirely nominated and voted on by Ohio students. The 2021 nominees are: Be Not Far from Me by Mindy McGinnis Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo The Girl in the White Van by April Henry The Inheritance Games by Jennifer Lynn Barnes The Invincible Summer of Juniper Jones by Daven McQueen Scan to vote starting September 1 Scan to nominate a book for the 2022 award The Teens’ Top Ten is a teen choice list, where teens nominate and choose their favorite books of the previous year. Nominators are members of teen book groups from sixteen school and public libraries around the country selected by the Young Adult Library Services Association to participate. Teens are encouraged to read the nominees throughout the summer to prepare for the national Teens’ Top Ten vote, which will take place Aug. 15 – Oct. 12. The 10 nominees that receive the most votes will be named the official 2021 Teens’ Top Ten. All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson All the Stars and Teeth by Adalyn Grace Atomic Women by Roseanne Montillo The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes by Suzanne Collins The Betrothed by Kiera Cass The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person by Frederick Joseph The Bone Thief by Breeana Shields Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas Chain of Gold by Cassandra Clare Clap When You Land by Elizabeth Acevedo Dangerous Secrets by Mari Mancusi The Dark Matter of Mona Starr by Laura Gulledge. -

Libraries, Power, and Justice Toward a Sociohistorically Informed Intellectual Freedom

Braverman Essay 2018 Libraries, Power, and Justice Toward a Sociohistorically Informed Intellectual Freedom By Alessandra Seiter his paper critically examines the concept of intellectual free- dom (IF) and the central role it plays in the U.S. library and Tinformation science (LIS) profession, challenging the concept’s assumed basis in neutrality and demonstrating the active barrier it presents in its current implementation to existing and future social justice efforts. The paper argues that if LIS is to move from making ineffective calls for equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) to actively working for justice within and beyond the field, then it must adopt an understanding of IF that fundamentally considers the sociohistorical context of power in LIS, the United States, and the world. IF and Neutrality in the ALA’s Codes of Ethics Though the American Library Association (ALA) has codified EDI in its main ethical frameworks – the 1996 Library Bill of Rights (LBR) and the 2008 Code of Ethics (COE) – it is reluctant to explicitly outline which groups of people are intended to benefit from these initiatives, much less the societal power structures underlying the need for them. This reluctance means that, rather than facilitating LIS work toward social justice for oppressed peoples, the ALA’s EDI efforts are absorbed into a framework of “neutral” IF which demands that LIS workers not enact policies or otherwise take actions that fall outside the status quo on an organizational or national level. In contrast to Alessandra Seiter is the Knowledge Services Librarian at the Harvard Kennedy School, where she specializes in digital, data, and spatial resources. -

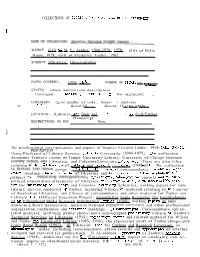

Online Finding

COLLECTIONS OF CORfillSPONDENCE hKD ~~NUSCRIPT DOCill1ENTS ') SOURCE: Gift of M. F., Tauber, 1966-1976; 1978; Gift of Ellis Mount, 1979; Gift of Frederick Tauber, 1982 SUBJECT: libraries; librarianship DATES COVERED: 1935- 19.Q2:;...·_· NUMBER OF 1TEHS; ca. 74,300- t - .•. ,..- STATUS: (check anoroor La te description) Cataloged: Listed:~ Arranged:-ll- Not organized; _ CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes> or shelves) vc Bound:,...... Boxed:231 Stro r ed; 11 tape reels LOCATION:- (Library) Rare Book and CALL~NtJHBER Ms Coll/Tauber Manuscript RESTRICTIONS ON USE None --.,.--....---------------.... ,.... - . ) The professional correspondence and papers of Maurice Falcolm Tauber, 1908- 198~ Melvil!. DESCRIPTION: Dewey Professor' of Library Service, C9lumbia University (1944-1975). The collection documents Tauber's career at Temple University Library, University of Chicago Graduate LibrarySghooland Libraries, and ColumbiaUniver.sity Libra.:t"ies. There are also files relating to his.. ~ditorship of College' and Research Libraries (1948...62 ). The collection is,d.ivided.;intot:b.ree series. SERIESL1) G'eneral correspondence; inchronological or4er, ,dealing with all aspects of libraries and librarianship•. 2)' Analphabet1cal" .subject fi.~e coni;ainingcorrespQndence, typescripts, .. mJnieographed 'reports .an~,.::;~lated printed materialon.allaspects of libraries and. librarianship, ,'lith numerou§''':r5lders for the University 'ofCh1cago and Columbia University Libraries; working papers for many library surveys conducted by Tauber, including 6 boxes of material relating to his survey of Australian libraries; and 2 boxes of correspondence and other material for Tauber and Lilley's ,V.S. Officeof Education Project: Feasibility Study Regarding the Establishment of an Educational Media Research Information Service (1960); working papers of' many American Library Association, American National Standards~J;:nstituteand other professional organization conferences and committee meetings. -

Racism and “Freedom of Speech”: Framing the Issues

Al Kagan Editorial Racism and “Freedom of Speech”: Framing the Issues The production and distribution of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom’s 1977 film was one of the most controversial and divisive issues in ALA history. The Speaker: A Film About Freedom was introduced at the 1977 ALA Annual Conference in Detroit, and was revived on June 30th, 2014, for a program in Las Vegas titled, “Speaking about ‘The Speaker.’” ALA Council’s Intellectual Freedom Committee (IFC) developed the program, which was cosponsored by the Freedom to Read Foundation (FTRF), the Library History Round Table and the ALA Black Caucus (BCALA). 4 Some background is necessary for context. This professionally made 42- minute color film was sponsored by the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom in 1977 and made in virtual secret without oversight by the ALA Executive Board or even most of the Intellectual Freedom Committee members. In fact, requests for information about the film, for copies of the script from members of these two bodies were repeatedly rebuffed. Judith Krug (now deceased), Director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom, was in charge with coordination from a two- member IFC subcommittee and ALA Executive Director Robert Wedgeworth. The film was made by a New York production company, and was envisioned by Krug as an exploration of the First Amendment in contemporary society. The film’s plot is a fictionalized account of real events. A high school invites a famous scientist (based on physicist and Nobel prizewinner William Shockley) to speak on his research claiming that black people are genetically Al Kagan is Professor of Library Administration and African Studies Bibliographer Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. -

IFRT Report 08 September1975.Pdf

INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM ROUND TABLE AMERICAN LIBRARY ~SSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON S T REET · CH ICAGO IL LINOI S 6 0 II · (3121 9 44-678 0 f.,.u l(j l..'o-~-r. '9?s IFRT REPORT -.<jli'; No . 8 , September 1975 From the Chairperson , David W. Brunton RECEIVED SEP 1 9 1975 AMERICAN In this REPORT ... LIB PARIES ~ Summaries of the intellectual freedom programs at t he 1975 Annual Con f e rence in San Francisco ~ Rundowns of actions taken at the meet)ngs of the IFRT Executi ve Committee , the IFRT membership, the Inte ll ectual Freedom Committee, and the Trustees of the Freedom to Read Foundati on ~ An important announcement con cerning the confidential it y of I ib rary records: a ruling from t he Te xa~ Attorney Ge nera l ~ A comp lete review of rece nt obsceni t y leg islation i n the fi fty states <><> IFRT and IFC Win Jones A\vard! For members of the Intellectual Freedom Round Table, the Intellectual Fr eedom Committee, and the Freedom to Read Four.dation , there couldn't have been a mo re pleasing way to close the San Francisco conference . At the inaugural luncheon which traditionally concludes ALA ' s annual meetings, it was announced tha t the IFRT and the IFC had been awarded $12,000 from the J . Morris Jones-World Book Encyclopedia-ALA Goals Award, to support the appeal in Moore v . Younge r, the suit brought by the Freedom to Read Found~tion against California's 1969 "harmful matte r" law. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

The Librarian

The Librarian RALPH MUNN DURINGTHE COURSE of the Public Library In- quiry Robert D. Leigh and his associates discovered that there is a strong basic belief among librarians which has inspired and sustained them through the years. Leigh isolated and defined this belief, calling it "the librarian's faith." He defined it as "a belief in the virtue of the printed word, especially of the book, the reading of which is held to be good in itself, or from its reading flows that which is good." l Although librarians may never have reduced this belief to a formal statement or thought of it as a faith, it is a principal part of their heritage. The librarian of 1954 wishes to accept this traditional faith of his fathers, but like the modern theologian he is disturbed by gnawing doubts. He has learned just enough from research to want some demonstrable facts to support his faith. Is there virtue in all reading? Is the reading of a light novel of more value than viewing its televised dramatization? Can the individual reader drain a book of its meaning, or must he match his reactions with those of others in a discussion group? What are the actual effects of reading upon the various categories of people? Though he lacks positive answers to these questions, the librarian still follows in the faith despite his doubts. Today, as in the past, he believes that there is virtue in the printed word-and in its audio- visual counterparts-and he acts upon it. It is still the determining factor in his decisions; it inspires him in his work, bringing to it a strong sense of social significance. -

Collection Development Policy Revisions

SAN MARCOS PUBLIC LIBRARY COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT POLICY The San Marcos Public Library collection development policy has been developed by the library board and staff for the purpose of providing a framework to guide the development of the library's collection. This policy is to be considered the official position of the library. A. Purpose of the Public Library The mission of the San Marcos Public Library is to serve as a source of information, education, recreation, and cultural enrichment by providing the community with free and convenient access to books, periodicals, audiovisual materials, information services, and educational programs. B. Priorities for Collection Development Because we have limited resources with which to work, we have chosen to emphasize the following priorities with regard to development of the library collection: 1) to develop a well-rounded collection of current, high-demand, high-interest materials in a variety of formats for persons of all ages; 2) to make available timely, accurate, and useful information through our reference services department; 3) to encourage children to develop an interest in reading and learning by providing them with an outstanding collection of library materials and by promoting use of the collection through programs and services aimed at children, parents, and teachers; 4) to encourage lifelong learning by providing independent adult learners with resources to assist them in achieving their educational goals; 5) to take a leadership role in collecting, preserving, and disseminating information of both current and historical interest on the San Marcos/Hays County area. Because of the availability of other outstanding Texana, genealogy, medical, law, and research libraries in the Austin-San Antonio area, the San Marcos Public Library will not endeavor to develop in-depth, research-oriented collections with the exception of our local history collection.