November, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Mesolithic Site in the Thal Desert of Punjab (Pakistan)

Asian Archaeology https://doi.org/10.1007/s41826-019-00024-z FIELD WORK REPORT Mahi Wala 1 (MW-1): a Mesolithic site in the Thal desert of Punjab (Pakistan) Paolo Biagi 1 & Elisabetta Starnini2 & Zubair Shafi Ghauri3 Received: 4 April 2019 /Accepted: 12 June 2019 # Research Center for Chinese Frontier Archaeology (RCCFA), Jilin University and Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2019 1Preface considered by a few authors a transitional period that covers ca two thousand years between the end of the Upper The problem of the Early Holocene Mesolithic hunter-gatherers Palaeolithic and the beginning of the Neolithic food producing in the Indian Subcontinent is still a much debated topic in the economy (Misra 2002: 112). The reasons why our knowledge prehistory of south Asia (Lukacs et al. 1996; Sosnowska 2010). of the Mesolithic period in the Subcontinent in general is still Their presence often relies on knapped stone assemblages insufficiently known is due mainly to 1) the absence of a de- characterised by different types of geometric microlithic arma- tailed radiocarbon chronology to frame the Mesolithic com- tures1 (Kajiwara 2008: 209), namely lunates, triangles and tra- plexes into each of the three climatic periods that developed pezes, often obtained with the microburin technique (Tixier at the beginning of the Holocene and define a correct time-scale et al. 1980; Inizan et al. 1992; Nuzhniy 2000). These tools were for the development or sequence of the study period in the area first recorded from India already around the end of the (Misra 2013: 181–182), 2) the terminology employed to de- nineteenth century (Carleyle 1883; Black 1892; Smith scribe the Mesolithic artefacts that greatly varies author by au- 1906), and were generically attributed to the beginning thor (Jayaswal 2002), 3) the inhomogeneous criteria adopted of the Holocene some fifty years later (see f.i. -

38 Antarctic Dry Valleys

38 Antarctic Dry Valleys: 1. The Antarctic environment and the Antarctic Dry Valleys. 2. Cold-based glaciers and their contrast with wet-based glaciers. 3. Microclimate zones in the Antarctic Dry Valleys (ADV) and their implications. 4. Landforms on Earth and Mars: A comparative analysis of analogs. 5. Biological activity in cold-polar deserts. 6. Problems in Antarctic Geoscience and their application to Mars. The Dry Valleys: A Hyper-Arid Cold Polar Desert Temperate Wet-Based Glaciers Cold-Based Glaciers Antarctic Dry Valleys: Morphological Zonation, Variable Geomorphic Processes, and Implications for Assessing Climate Change on Mars Antarctic Dry Valleys • 4000 km2; Mountain topography – (2800 m relief). • Coldest, driest desert on Earth. • Mean annual temperature: -20o C. • Mean annual snowfall (CWV): – Min. = <0.6 cm; Max. = 10 cm. – Fate of snow: Sublimate or melt. • A hyperarid cold polar desert. • Topography controls katabatic wind flow: – Funneled through valleys, warmed by adiabatic compression. – Enhances surface temperatures, increases sublimation rates of ice and snow. • Bedrock topography governs local distribution of snow and ice: • Biology sparse: ~1 mm “Antarctic mite”; microscopic nematodes. • Environment very useful for understanding Mars climate change. Antarctic Dry Valleys • 4000 km2; Mountain topography – (2800 m relief). • Coldest and driest desert on Earth. • Mean annual temperature: -20o C. • Mean annual snowfall (CWV): – Minimum = <0.6 cm; Maximum = 10 cm. – Fate of snow: Sublimate or melt. • Generally a hyperarid cold polar desert. • Topography controls katabatic wind flow: – Funneled through valleys, warmed by adiabatic compression. – Enhance surface temperatures, increase sublimation rates of ice and snow. • Bedrock topography governs local distribution of snow and ice: • Biology sparse: ~1 mm-sized “Antarctic mite”; microscopic nematodes. -

Prickly News South Coast Cactus & Succulent Society Newsletter | Feb 2021

PRICKLY NEWS SOUTH COAST CACTUS & SUCCULENT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER | FEB 2021 Guillermo ZOOM PRESENTATION SHARE YOUR GARDEN OR YOUR FAVORITE PLANT Rivera Sunday, February 14 @ 1:30 pm Cactus diversity in northwestern Argentina: a habitat approach I enjoyed Brian Kemble’s presentation on the Ruth Bancroft Garden in Walnut Creek. For those of you who missed the presentation, check out the website at https://www. ruthbancroftgarden.org for hints on growing, lectures and access to webinars that are available. Email me with photos of your garden and/or plants Brian graciously offered to answer any questions that we can publish as a way of staying connected. or inquiries on the garden by contacting him at [email protected] [email protected]. CALL FOR PHOTOS: The Mini Show genera for February are Cactus: Eriosyce (includes Neoporteria, Islaya and Neochilenia) and Succulent: Crassula. Photos will be published and you will be given To learn more visit southcoastcss.org one Mini-show point each for a submitted photo of your cactus, succulent or garden (up to 2 points). Please include your plant’s full name if you know it (and if you don’t, I will seek advice for you). Like us on our facebook page Let me know if you would prefer not to have your name published with the photos. The photos should be as high resolution as possible so they will publish well and should show off the plant as you would Follow us on Instagram, _sccss_ in a Mini Show. This will provide all of us with an opportunity to learn from one another and share plants and gardens. -

Educator Guide

E DUCATOR GUIDE This guide, and its contents, are Copyrighted and are the sole Intellectual Property of Science North. E DUCATOR GUIDE The Arctic has always been a place of mystery, myth and fascination. The Inuit and their predecessors adapted and thrived for thousands of years in what is arguably the harshest environment on earth. Today, the Arctic is the focus of intense research. Instead of seeking to conquer the north, scientist pioneers are searching for answers to some troubling questions about the impacts of human activities around the world on this fragile and largely uninhabited frontier. The giant screen film, Wonders of the Arctic, centers on our ongoing mission to explore and come to terms with the Arctic, and the compelling stories of our many forays into this captivating place will be interwoven to create a unifying message about the state of the Arctic today. Underlying all these tales is the crucial role that ice plays in the northern environment and the changes that are quickly overtaking the people and animals who have adapted to this land of ice and snow. This Education Guide to the Wonders of the Arctic film is a tool for educators to explore the many fascinating aspects of the Arctic. This guide provides background information on Arctic geography, wildlife and the ice, descriptions of participatory activities, as well as references and other resources. The guide may be used to prepare the students for the film, as a follow up to the viewing, or to simply stimulate exploration of themes not covered within the film. -

The Amazing Life in the Indian Desert

THE AMAZING LIFE IN THE INDIAN DESERT BY ISHWAR PRAKASH CENTRAL ARID ZONE RESEARCH INSTITUTE JODHPUR Printed June, 1977 Reprinted from Tbe Illustrated Weekly of India AnDual1975 CAZRI Monogra,pp No. 6 , I Publtshed by the Director, Central Arid Zone Research Institute, Jodhpur, and printed by B. R. Chowdhri, Press Manager at Hl!ryana Agricultural University Press, Hissar CONTENTS A Sorcerer's magic wand 2 The greenery is transient 3 Burst of colour 4 Grasses galore 5 Destruction of priceless teak 8 Exciting "night life" 8 Injectors of death 9 Desert symphony 11 The hallowed National Bird 12 The spectacular bustard 12 Flamingo city 13 Trigger-happy man 15 Sad fate of the lord of the jungle 16 17 Desert antelopes THE AMAZING LIFE IN THE INDIAN DESERT The Indian Desert is not an endless stretch of sand-dunes bereft of life or vegetation. During certain seasons it blooms with a colourful range of trees and grasses and abounds in an amazing variety of bird and animal life. This rich natural region must be saved from the over powering encroachment of man. To most of us, the word "desert" conjures up the vision of a vast, tree-less, undulating, buff expanse of sand, crisscrossed by caravans of heavily-robed nomads on camel-back. Perhaps the vision includes a lonely cactus plant here and the s~ull of some animal there and, perhaps a few mini-groves of date-palm, nourished by an artesian well, beckoning the tired traveller to rest awhile before riding off again to the horizon beyond. This vision is a projection of the reality of the Saharan or the Arabian deserts. -

Plethora of Plants - Collections of the Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb (2): Glasshouse Succulents

NAT. CROAT. VOL. 27 No 2 407-420* ZAGREB December 31, 2018 professional paper/stručni članak – museum collections/muzejske zbirke DOI 10.20302/NC.2018.27.28 PLETHORA OF PLANTS - COLLECTIONS OF THE BOTANICAL GARDEN, FACULTY OF SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF ZAGREB (2): GLASSHOUSE SUCCULENTS Dubravka Sandev, Darko Mihelj & Sanja Kovačić Botanical Garden, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Marulićev trg 9a, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia (e-mail: [email protected]) Sandev, D., Mihelj, D. & Kovačić, S.: Plethora of plants – collections of the Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb (2): Glasshouse succulents. Nat. Croat. Vol. 27, No. 2, 407- 420*, 2018, Zagreb. In this paper, the plant lists of glasshouse succulents grown in the Botanical Garden from 1895 to 2017 are studied. Synonymy, nomenclature and origin of plant material were sorted. The lists of species grown in the last 122 years are constructed in such a way as to show that throughout that period at least 1423 taxa of succulent plants from 254 genera and 17 families inhabited the Garden’s cold glass- house collection. Key words: Zagreb Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, historic plant collections, succulent col- lection Sandev, D., Mihelj, D. & Kovačić, S.: Obilje bilja – zbirke Botaničkoga vrta Prirodoslovno- matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu (2): Stakleničke mesnatice. Nat. Croat. Vol. 27, No. 2, 407-420*, 2018, Zagreb. U ovom članku sastavljeni su popisi stakleničkih mesnatica uzgajanih u Botaničkom vrtu zagrebačkog Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta između 1895. i 2017. Uređena je sinonimka i no- menklatura te istraženo podrijetlo biljnog materijala. Rezultati pokazuju kako je tijekom 122 godine kroz zbirku mesnatica hladnog staklenika prošlo najmanje 1423 svojti iz 254 rodova i 17 porodica. -

Automated Detection of Archaeological Mounds Using Machine-Learning Classification of Multisensor and Multitemporal Satellite Data

Automated detection of archaeological mounds using machine-learning classification of multisensor and multitemporal satellite data Hector A. Orengoa,1, Francesc C. Conesaa,1, Arnau Garcia-Molsosaa, Agustín Lobob, Adam S. Greenc, Marco Madellad,e,f, and Cameron A. Petriec,g aLandscape Archaeology Research Group (GIAP), Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology, 43003 Tarragona, Spain; bInstitute of Earth Sciences Jaume Almera, Spanish National Research Council, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; cMcDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, CB2 3ER Cambridge, United Kingdom; dCulture and Socio-Ecological Dynamics, Department of Humanities, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 08005 Barcelona, Spain; eCatalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies, 08010 Barcelona, Spain; fSchool of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2000, South Africa; and gDepartment of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, CB2 3DZ Cambridge, United Kingdom Edited by Elsa M. Redmond, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, and approved June 25, 2020 (received for review April 2, 2020) This paper presents an innovative multisensor, multitemporal mounds (7–9). Georeferenced historical map series have also machine-learning approach using remote sensing big data for been used solely or in combination with contemporary declas- the detection of archaeological mounds in Cholistan (Pakistan). sified data (10–14). In recent years, RS-based archaeological The Cholistan Desert presents one of -

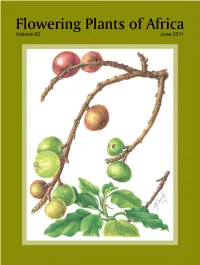

Albuca Spiralis

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J. -

Desert-2.Pdf

Desert Contens Top Ten Facts PG 1 front cover 1 All Deserts are all different but they all have low amounts of rain PG 2 contens 2 Deserts normally have less than 40 CM a year 3 The Sahara desert is in Northern Africa and is over 12 different countries PG 3 top ten facts 4 Sahara desert is the largest desert in the Earth PG 4 whether and climate 5 Only around 20% of the Deserts on Earth are covered in sand 6 Around one third of the Earth's surface is covered in Desert PG 5 desert map 7 The largest cold Desert on Earth is Antarctica PG 6 animals and people that live there 8 Located in South America, the Atacama Desert is the driest place in the world PG 7 what grows there 9 Lots of animals live in Deserts such as the wild dog 10 The Arabian Desert in the Middle East is the second largest hot desert on Earth but is substantially smaller than the Sahara. This is a list of the deserts in Wether And Climate the world Arabian Desert. ... Kalahari Desert. ... Wether Mojave Desert. ... Sonoran Desert. ... Chihuahuan Desert. ... This is a map showing Deserts are usually very, very dry. Even the wettest deserts get less than ten Thar Desert. ... the deserts in the world inches of precipitation a year. In most places, rain falls steadily throughout the Gibson Desert. year. But in the desert, there may be only a few periods of rains per year with a lot of time between rains. -

Phylogenetic Placement and Generic Re-Circumscriptions of The

TAXON 65 (2) • April 2016: 249–261 Powell & al. • Generic recircumscription in Schlechteranthus Phylogenetic placement and generic re-circumscriptions of the multilocular genera Arenifera, Octopoma and Schlechteranthus (Aizoaceae: Ruschieae): Evidence from anatomical, morphological and plastid DNA data Robyn F. Powell,1,2 James S. Boatwright,1 Cornelia Klak3 & Anthony R. Magee2,4 1 Department of Biodiversity & Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville, Cape Town, South Africa 2 Compton Herbarium, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X7, Claremont 7735, Cape Town, South Africa 3 Bolus Herbarium, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, 7701, Rondebosch, South Africa 4 Department of Botany & Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa Author for correspondence: Robyn Powell, [email protected] ORCID RFP, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7361-3164 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.12705/652.3 Abstract Ruschieae is the largest tribe in the highly speciose subfamily Ruschioideae (Aizoaceae). A generic-level phylogeny for the tribe was recently produced, providing new insights into relationships between the taxa. Octopoma and Arenifera are woody shrubs with multilocular capsules and are distributed across the Succulent Karoo. Octopoma was shown to be polyphyletic in the tribal phylogeny, but comprehensive sampling is required to confirm its polyphyly. Arenifera has not previously been sampled and therefore its phylogenetic placement in the tribe is uncertain. In this study, phylogenetic sampling for nine plastid regions (atpB-rbcL, matK, psbJ-petA, rpl16, rps16, trnD-trnT, trnL-F, trnQUUG-rps16, trnS-trnG) was expanded to include all species of Octopoma and Arenifera, to assess phylogenetic placement and relationships of these genera. -

Plants, Volume 1, Number 1 (August 1979)

Desert Plants, Volume 1, Number 1 (August 1979) Item Type Article Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 02/10/2021 01:18:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/528188 Volume I. Number 1. August 1979 Desert Published by The University of Arizona for the Plants Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum Assisting Nature with Plant Selection4 Larry K. Holzworth Aberrant Sex -Ratios in Jojoba Associated with Environmental Factors 8 Serena L. Cole 'J. G. Lemmon & Wife,' Plant Explorers in Arizona, California, and Nevada12 Frank S. Crosswhite 'Extinct' Wire -Lettuce, Stephanomeria schottii (Compositae), Rediscovered in Arizona after More Than One Hundred Years22 Elinor Lehto Southwestern Indian Sunflowers23 Gary Paul Nabhan Transition from a Bermudagrass Lawn to a Landscape of Rock or Gravel Mulch 27 Charles Sacamano Preliminary Evaluation of Cold- hardiness in Desert Landscaping Plants at Central Arizona College29 William A. Kinnison Effects of the 1978 Freeze on Native Plants of Sonora, Mexico33 Warren D. Jones The Severe Freeze of 1978 -79 in the Southwestern United States37 The National Climate Program Act of 197840 Reviews42 Arboretum Progress46 R. T. McKittrick Volume 1. Number 1. August 1979 Published by The University of Arizona Desert Plants for the Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum The Severe Freeze of 1978 -79 in the Contents Southwestern United States37 Correspondents: Editorial Barrie D. Coate, Saratoga Horticultural Foundation; Dara E. Emery, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden; Louis C. Assisting Nature with Plant Selection 4 Erickson, Botanic Gardens, University of California, River- Larry K. Holzworth, USDA Soil Conservation side; Wayne L. -

World Deserts

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY World Deserts Reader Frog in the Australian Outback Joshua tree in the Mojave Desert South American sheepherder Camel train across the Sahara Desert THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. World Deserts Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work.