Students and Teachers Use an Online AP CS Principles Ebook Di Erently

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel D. Garcia

DANIEL D. GARCIA [email protected] http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~ddgarcia/ 777 Soda Hall #1776 UC Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-1776 (510) 517-4041 ______________________________________________________ EDUCATION MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Cambridge, MA B.S. in Computer Science, 1990 B.S. in Electrical Engineering, 1990 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Berkeley, CA M.S. in Computer Science, 1995 Ph.D. in Computer Science, 2000. Area: computer graphics and scientific visualization. Brian Barsky, advisor. TEACHING AWARDS • Outstanding Graduate Student Instructor in Computer Science (1992) • Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Outstanding Graduate Student Instructor (1997) • Computer Science Division Diane S. McEntyre Award for Excellence in Teaching (2002) • Computer Science Division IT Faculty Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching (2005) • UC Berkeley “Everyday Hero” Award (2005) • Highest “teaching effectiveness” rating for any EECS lower division instructor, ever (6.7, since tied) (2006) • CS10: The Beauty and Joy of Computing chosen as 1 of 5 national pilots for AP CS: Principles course (2010) • CS10: The Beauty and Joy of Computing chosen as a University of California Online Course Pilot (2011) • Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) Distinguished Educator (2012) • Top 5 Professors to Take Classes with at UC Berkeley, The Black Sheep Online (2013) • CS10 becomes first introductory computing class at UC Berkeley with > 50% women (2013,2014) • Ten Most Popular MOOCs Starting in September 2015 and January 2016, Class Central (2015, 2016) • LPFI's Lux Award for being “Tech Diversity Champion” (2015) • NCWIT’s Undergraduate Research Mentoring (URM) Award (2016) • NCWIT’s Extension Services Transformation Award, Honorable Mention (2016) • CS10 becomes first introductory computing class at UC Berkeley with > 60% women (2017) • SAP Visionary Member Award (2017) • Google CS4HS Ambassador (2017) • CS10 becomes first introductory computing class at UC Berkeley with > 65% women (2018) Updated through 2018-07-01 1 / 28 Daniel D. -

Mark Guzdial School of Interactive Computing, College of Computing, Georgia Institute of Technology Thursday, January 31, 2013 9:00-10:00Am State Room East, IMU

Mark Guzdial School of Interactive Computing, College of Computing, Georgia Institute of Technology Thursday, January 31, 2013 9:00-10:00am State Room East, IMU Topic: Three Lessons in Teaching Computing To Everyone My colleagues and I have been studying how to teach computer science, to CS majors, Abstract: to non-CS undergraduates, and to adult professionals. In this talk, I’ll talk about some of what we’ve learned, organized around three lessons. Lesson #1: We typically teach computer science too abstractly, and by teaching it in a context (e.g., media, robots, Nintendo GameBoys, Photoshop), we can dramatically improve success (retention and learning) for both traditional and non-traditional CS learners. Lesson #2: Collaboration can create opportunities for learning, but classroom culture (e.g., competition) trumps technology (Wikis). Lesson #3: Our greatest challenge in computer science education is improving teaching, and that will require changes in high schools, in public policy, and in universities. Biography: Mark Guzdial is a Professor in the School of Interactive Computing in the College of Computing at Georgia Institute of Technology. His research focuses on learning sciences and technology, specifically, computing education research. He has published several books on the use of media as a context for learning computing. He was the original developer of the "Swiki" which was the first wiki designed for educational use. He was awarded a joint Ph.D. degree in Education and Computer Science from the University of Michigan in 1993. He serves on the ACM's Education Council and the Special Interest Group in CS Education (SIGCSE) Board, and is on the editorial boards of the "Journal of the Learning Sciences," "ACM Transactions on Computing Education," and "Communications of the ACM." With his wife and colleague, Barbara Ericson, he received the 2010 ACM Karl V. -

42 a Systematic Investigation of Replications in Computing

A Systematic Investigation of Replications in Computing Education Research QIANG HAO, DAVID H. SMITH IV, NAITRA IRIUMI, and MICHAIL TSIKERDEKIS, Western Washington University AMY J. KO, University of Washington As the societal demands for application and knowledge in computer science (CS) increase, CS student en- rollment keeps growing rapidly around the world. By continuously improving the efficacy of computing education and providing guidelines for learning and teaching practice, computing education research plays a vital role in addressing both educational and societal challenges that emerge from the growth of CS students. Given the significant role of computing education research, it is important to ensure the reliability ofstudies in this field. The extent to which studies can be replicated in a field is one of the most important standards for reliability. Different fields have paid increasing attention to the replication rates of their studies, butthe replication rate of computing education was never systematically studied. To fill this gap, this study inves- tigated the replication rate of computing education between 2009 and 2018. We examined 2,269 published studies from three major conferences and two major journals in computing education, and found that the overall replication rate of computing education was 2.38%. This study demonstrated the need for more repli- cation studies in computing education and discussed how to encourage replication studies through research initiatives and policy making. CCS Concepts: • Social and professional topics → Computing education; Additional Key Words and Phrases: Computing education, replications, computer science education, replica- tion rate, assessment, evaluation, content analysis, educational policy, research methodology ACM Reference format: Qiang Hao, David H. -

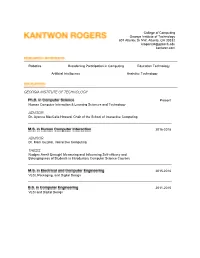

Georgia Institute of Technology Advisor Advisor Thesis

College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology 801 Atlantic Dr NW, Atlanta, GA 30332 [email protected] kantwon.com Robotics Broadening Participation in Computing Education Technology Artificial Intelligence Assistive Technology GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Present Human Computer Interaction & Learning Sciences and Technology ADVISOR Dr. Ayanna MacCalla Howard, Chair of the School of Interactive Computing 2016-2018 ADVISOR Dr. Mark Guzdial, Interactive Computing THESIS Nudges Aren’t Enough! Measuring and Influencing Self-efficacy and Belongingness of Students in Introductory Computer Science Courses 2015-2016 VLSI, Packaging, and Digital Design 2011-2015 VLSI and Digital Design GOOGLE Summer 2019 Designed, developed, and executed user study and data analysis for eye-tracking research project within the education realm. LEVELED UP Summer 2018 Start-up designed to create a one-stop-shop of STEM opportunities for minority students. Recipient of $20,000 seed funding from Georgia Tech INTEL CORPORATION Summer 2018 Designed Python-based network visualizations used by over 50 engineers in the Xeon supercomputer architecture team Proposed future system-design recommendations to increase the usability and efficiency of graph visualizations Summer 2017 Created educational lesson plans for Intel’s Future Skills program to expose underrepresented minority students to STEM. Topics include internet of things, drones, and introductory programming. Curricula have been shipped nation-wide and are used by hundreds of learners. Summer 2016 Designed and implemented JavaScript and AngularJS based features in task organization web application used by over 30,000 Intel employees. Summer 2015 Produced data-mining TCL script to analyze design change lists to increase efficiency of chip-design timing convergence INSTRUCTOR Fall 2016-Present 1,000+ student undergraduate course focused on introducing programming concepts including data manipulation, data visualization, algorithm design, and graph theory. -

MIRANDA C. PARKER, PH.D. Postdoctoral Scholar University of California, Irvine [email protected] Mirandacparker.Com

MIRANDA C. PARKER, PH.D. Postdoctoral Scholar University of California, Irvine [email protected] mirandacparker.com EDUCATION Ph.D., Human-Centered Computing August 2014 - December 2019 Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA Advisor: Mark Guzdial Dissertation Title: \An Analysis of Supports and Barriers to Offering Computer Science in Georgia Public High Schools" Dissertation Committee Members: Betsy DiSalvo, Rebecca E. Grinter, Willie Pearson, Jr., Leigh Ann DeLyser Bachelor of Science, Computer Science August 2010 - May 2014 Harvey Mudd College, Claremont, CA Graduated with Honors in Computer Science PROFESSIONAL AND RESEARCH EXPERIENCE 2020-present University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA Postdoctoral Scholar, School of Education (with Mark Warschauer) Spring 2020 Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA Postdoctoral Fellow, Constellations Center 2014-2019 Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA Graduate Research Assistant, School of Interactive Computing (with Mark Guzdial) Summer 2016 Code.org Research Intern, K-12 Computer Science Framework RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS Peer-Reviewed Conference Papers Miranda C. Parker, Amber Solomon, Brianna Pritchett, David A. Illingworth, Lauren E. Margulieux, Mark Guzdial. \Socioeconomic Status and Computer Science Achievement: Spatial Ability as a Mediating Variable in a Novel Model of Understanding," ICER, 2018. Miranda C. Parker, Kantwon Rogers, Barbara J. Ericson, Mark Guzdial. \Students and Teachers Use An Online AP CS Principles EBook Differently: Teacher Behavior Consistent with Expert Learners," ICER, 2017. Miranda C. Parker, Leigh Ann DeLyser. \Concepts and Practices: Designing and Developing A Modern K{12 CS Framework," SIGCSE, 2017. Miranda C. Parker, Mark Guzdial, Shelley Engleman. \Replication, Validation, and Use of a Language Inde- pendent CS1 Knowledge Assessment," ICER, 2016. -

Novices' Learning Barriers When Using Code Examples in Open

Novices’ Learning Barriers When Using Code Examples in Open-Ended Programming Wengran Wang, Archit Kwatra, James Skripchuk, Neeloy Gomes, Alexandra Milliken, Chris Martens, Tiffany Barnes, Thomas Price North Carolina State University Raleigh, NC, USA ABSTRACT Open-ended projects can prove very difficult for novices [14], in Open-ended programming increases students’ motivation by allow- part because they encourage novices to design unique programs ing them to solve authentic problems and connect programming that address their interests and goals, which may require them to use to their own interests. However, such open-ended projects are also new programming features, or accomplish new tasks, beyond what challenging, as they often encourage students to explore new pro- they have already learned. Novices can also struggle to combine gramming features and attempt tasks that they have not learned the individual programming concepts they have learned (e.g. loops, before. Code examples are effective learning materials for students variables, etc.) into a complete program [14], and they may lack and are well-suited to supporting open-ended programming. How- experience making use of code blocks or libraries offered by the ever, there is little work to understand how novices learn with language (i.e. APIs [10]). examples during open-ended programming, and few real-world de- Code examples are a common way for programmers to learn ployments of such tools. In this paper, we explore novices’ learning new APIs and coding patterns [4], and are also considered one of barriers when interacting with code examples during open-ended the most useful learning material for novices [24]. -

David J. Malan

David J. Malan 33 Oxford Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138 USA [email protected] https://cs.harvard.edu/malan education Harvard University, School of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2002 – 2007 Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), Computer Science. Research in cybersecurity and digital forensics with focus on detection of patterns in large datasets. Dissertation on Rapid Detection of Botnets through Collaborative Networks of Peers. Advised by Michael D. Smith. Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences 2002 – 2004 Master of Science (S.M.), Computer Science. Research in sensor networks for emergency medical care. Harvard College 1995 – 1999 Bachelor of Arts (A.B.), cum laude, Computer Science; 3.9 of 4.0 GPA in field. Related studies in government, micro- and macro-economics, finance, statistics and probability, multivariate calculus, and linear algebra. research interests Cybersecurity, digital forensics, botnets, computer science education, distance learning, collaborative learning, computer-assisted instruction. experience Harvard University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Graduate School of Education 2007 – Gordon McKay Professor of the Practice of Computer Science, Member of the Faculty of Education. Senior member of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Instructor for CS50, largest course at Harvard University with 763 students as of 2019 (+478% since 2006) and largest MOOC on edX with 3M+ registrants, also offered at Yale University. Manage staff of 80+. Oversee community of 150+ high schools teaching CS50 AP, College Board-endorsed adaptation of course. Instructor for CS50 for MBAs at Harvard Business School and CS50 for JDs at Harvard Law School, higher-level adaptations of course for professional audiences. Mindset Media, LLC 2008 – 2011 Chief Information Officer (CIO). -

Teaching the Nintendo Generation to Program Mark Guzdial, Elliot Soloway

Teaching the Nintendo Generation to Program Mark Guzdial, Elliot Soloway While the phrase “New Economy” doesn’t hold the same promise that it did for the dot- commers a couple years ago, we all still recognize that Information Technology has become the backbone of the world’s economy. The National Science Foundation’s Information Technology Research program was developed in response to the PITAC (1999) report which said as much. Even in the down-turned economy, there are still huge numbers of IT jobs that are going unfilled. Of course, none of this is news for those of us in the trenches teaching Computer Science. Our enrollments are bulging at the seams. We can’t get enough faculty to cover the loads. Despite those enormous enrollments, there are lots of indications that we’re not doing enough, or not doing the right things, to meet the demand for a diverse, well-educated, large workforce of Computer Science professionals. Start asking around—we’re hearing about drop-out/failure rates in CS1 courses in the 15-30% range. A just published report in the ACM SIGCSE Bulletin from a working group at ITICSE 2001 this last summer found shockingly low performance on simple programming problems, even among second year students, at four schools in three different countries (McCracken et al., 2001). (These results echo our research from 15 years ago, so it’s not clear that we ever have figured out how to teach programming.) The American Association for University Women’s (AAUW) report, Tech-Savvy: Educating Girls in the Computer Age (2000) points out that large numbers of women drop out or simply fail to enroll in Computer Science courses because they perceive CS courses to be overly technical, with little room for individual creativity Why are we doing such a poor job at getting and keeping students in Computer Science? Here’s our suggestion: computer science educators are using an out-dated view of computing and students. -

Design Process for a Non-Majors Computing Course

Design Process for a Non-majors Computing Course Mark Guzdial Andrea Forte College of Computing/GVU College of Computing/GVU Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology 801 Atlantic Drive 801 Atlantic Drive Atlanta, Georgia Atlanta, Georgia [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT course in computing, including a requirement to learn and There is growing interest in computing courses for non-CS use programming. When that decision was made, the only majors. We have recently built such a course that has met class available was our majors-focused CS1 based on the with positive response. We describe our design process, TeachScheme approach[7], which did not adequately meet which includes involvement of stakeholders and identifying the needs of our liberal arts, architecture, and management a context that facilitates learning. We present evaluation students. The course saw low success rates, and the stu- results on success rates (approximately 90% of the students dents and faculty were vocal in their dissatisfaction. We earn an A, B, or C) and impact of the course on students saw this dissatisfaction as an opportunity to create a new over time (80% report that the class has influenced them course and build toward Alan Perlis’ vision of programming more than a semester later). for all students—as a component of a general, liberal edu- cation [8]. The course that we developed, Introduction to Media Com- Categories and Subject Descriptors putation, is an introduction to computing contextualized K.4 [Computers and Education]: Computer and Infor- around the theme of manipulating and creating media. -

Technology for Teaching the Rest of Us

Technology for Teaching the Rest of Us Mark Guzdial School of Interactive Computing Story • Computing is important for more than just those who choose to major in computing. • Who are “they” (“the rest of us”)? What do they want from CS, and why aren’t they in our classes? How do they now learn CS? • Teaching those who do not want to become software engineers or computer scientists • The Story of Computing for All at Georgia Tech. • Our problem isn’t enrollment. • Meeting the needs of “the rest of us” with technology: 1. Matching or tailoring the context to the person. 2. How to find what they really want and need. 3. Teaching CS concepts without apprenticeship. The typical CS student: Future Software Engineer • To produce reliable, robust, secure software. • To work in interdisciplinary teams. • To use appropriate design notations, such as UML. • To work in multiple programming languages. Taulbee Numbers 2010 CRA Taulbee Survey of PhD- granting institutions! Who wants what CS has to ofer? • Computing is at the core of the modern society and modern economy. • Computing is key to innovation in many disciplines. • Computer Science has a much larger potential audience beyond software developers. • Estimates: ~13 million non-professional programmer/end-user programmers in US by 2012, vs. ~3 million professional software developers (Scaffidi, Shaw, & Myers, 2005) 5 The Two Cultures An atypical CS student: Future computational scientist or engineer • To use computation as a tool to enhance understanding. • To write programs of (at most) 100 lines (most often, 10 lines) for themselves. • They care about the products of the programs, not the programs. -

Guzdial • November, 2009 1 MARK J. GUZDIAL Professor College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology EDUCATIONAL BACKGROU

MARK J. GUZDIAL Professor College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND Ph.D. 1993 University of Michigan Education and Computer Science and Engineering M.S. 1986 University of Michigan Computer Science and Engineering B.S. 1984 Wayne State University Computer Science EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Professor College of Computing 2005 -Present Georgia Institute of Technology Associate Professor College of Computing 1999 -2005 Georgia Institute of Technology Assistant Professor College of Computing 1993 -1999 Georgia Institute of Technology Member of Technical Staff Bell Communications Research 1984 -1987 CURRENT FIELDS OF INTEREST Computing education research, computer-supported collaborative learning, multimedia composition environments, software-realized scaffolding, log file analysis. Dr. Guzdial's research centers on facilitating project-based learning: student learning through doing. He focuses on computing education. His Contextualized Support for Learning has the goal of enabling collaborative DynaBooks , in reference to the early vision of the computer as a personal tool for creating, experiencing, and sharing dynamic media for learning. A major focus of his research recently has been the development of a media-focused introduction to computing sequence that is particularly successful at broadening participation in computing. Websites of interest: • Home page: http://www.cc.gatech.edu/~mark.guzdial and http://home.cc.gatech.edu/guzdial • Group page: http://home.cc.gatech.edu/csl • Dr. Guzdial directs the NSF Broadening Participation in Computing Alliance, “ Georgia Computes!”: http://www.gacomputes.org • His approach to supporting computing through a media context is called “ Media Computation ”: http://www.mediacomputation.org I. TEACHING A. Courses Taught Computer Supported Collaborative Learning, Computer Music Implementation, Objects and Design, Introduction to Media Computation, Representing Structure and Behavior, Introduction to Educational Technology, Senior Design for Computational Media. -

Computing Education As a Foundation for 21St Century Literacy

Computing Education as a Foundation for 21st Century Literacy Mark Guzdial University of Michigan, Computer Science & Engineering Ann Arbor, Michigan [email protected] ABSTRACT Like Perlis, Seymour Papert was interested in the computer as a Teaching programming as a way to express ideas, communicate support for learning activities, especially for children. He made the with others, and understand our world is one of the oldest goals for claim “that children can learn to program and learning to program computing education. The inventor of the term “computer science” can affect the way that they learn everything8 else"[ ]. His point saw it as the third leg of STEM literacy. In this talk, I lay out the is not to teach computer science for its own sake, or as vocational history of the idea of universal computational literacy, some of training, but as a support for learning in any discipline. what it will take to get there, and how our field will be different The earliest reason for teaching students about computers was when we do. to support learning in science, engineering, and mathematics (what we now call STEM). George Forsythe published the term computer CCS CONCEPTS science in an article in the Journal of Engineering Education [4]. For Forsyth, computers were the third leg of literacy for STEM • Social and professional topics → Computing education; • students. He wrote in 1968 [5], “The most valuable acquisitions in Applied computing → Interactive learning environments. a scientific or technical education are the general-purpose mental KEYWORDS tools which remain serviceable for a lifetime. I rate natural language and mathematics as the most important of these tools, and computer computational literacy, CS for All, computational thinking, history science as a third.” ACM Reference Format: Alan Kay [7] and Andrea diSessa [2] used the term “literacy” Mark Guzdial.