THE FILMS of JACK CHAMBERS by Irene Bindi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highway Wherever: on Jack Chambers's 401 Towards London No.1

MATTHEW RYAN SMITH Highway Wherever: On Jack Chambers’s 401 Towards London No.1 ≈ The story behind Jack Chambers's painting 1 01 Towards London No. 1 (1968-69) is something like this: Chambers left London, Ontario for a meeting in Toronto. As he drove over the Exit 232 overpass near Woodstock, he glanced in his rear-view mirror and was struck by what he sa w behind him. He returned later that night and the next morning with a camera to photograph the area. The result is an archive of images taken above and around a banal overpass in Southwestern Ontario, later used as source material for one of Canada's most important landscape paintings. Chambers was born in l 93 l in London, Ontario, the gritty and spra wling half way point between Detroit/Windsor and Toronto. Inthe late 1950s and 1960s, Chambers and other local artists-including John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, Murray Favro, Bev Kelly, Ron Martin, David Rabinowitch, Royden Rabinovwitch, Walter Redinger, Tony Urquhart, and Ed Zclcnak-centralizcd the city of London in their artistic and social activities. As the 60s drew to a close, art historian Barry Lord wrote in Art in America that London was fast becoming "the most important art centre in Canada and a model for artists working elsewhere" and "the site of 'Canada's first regional liberation front."' In effect, the London Regionalism movement, as it became known, dismissed the stereotype that the local was trivial, which lent serious value to the fortunate moment where the artists found themselves: together in London making art about making art in London. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

F19-ACI-Catalogue.Pdf

The Canadian Art Library Fall 2019 Table of Contents 2 Molly Lamb Bobak: Life & Work by Michelle Gewurtz, Sara Angel 3 Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald: Life & Work by Michael Parke-Taylor, Sara Angel 4 Greg Curnoe: Life & Work by Judith Rodger, Sara Angel 5 Shuvinai Ashoona: Life & Work by Nancy G. Campbell, Sara Angel The Canadian Art Library 1 The Canadian Art Library Fall 2019 Molly Lamb Bobak Life & Work By (author) Michelle Gewurtz , Introduction by Sara Angel Sep 25, 2019 | Hardcover , Dust jacket | $40.00 Canada’s first woman war artist, Molly Lamb Bobak fought gender bias in the early twentieth century to become one of the country’s most important artists. Today she is revered for her groundbreaking paintings of military life as well as depictions of urban activity and crowd scenes that capture daily life in Canada. The daughter of celebrated photographer Harold Mortimer-Lamb, Vancouver- born artist Molly Lamb Bobak (1920–2014) joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps in 1942 and was sent overseas to London, becoming the first Canadian woman war artist. She brashly captured women’s military life and roles during the Second World War in her paintings, illustrated diaries, and drawings, depicting 9781487102050 female military training as well as dynamic scenes of marches and parades. The Canadian Art Library Upon her return to Canada, Bobak married fellow war artist Bruno Bobak, and the Art Canada Institute couple settled in Fredericton, New Brunswick, where they lived and worked for over half a century. One of the first Canadian female painters to earn her living as an artist, Bobak was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1973 and Subject presented with the Order of Canada in 1995. -

William Kurelek Life & Work by Andrew Kear

William Kurelek Life & Work by Andrew Kear 1 William Kurelek Life & Work by Andrew Kear Contents 03 Biography 19 Key Works 48 Significance & Critical Issues 62 Style & Technique 76 Where to See 88 Notes 95 Glossary 101 Sources & Resources 108 About the Author 109 Credits 2 William Kurelek Life & Work by Andrew Kear The art of William Kurelek (1927–1977) navigated the unsentimental reality of Depression-era farm life and plumbed the sources of the artist’s debilitating mental suffering. By the time of his death, he was one of the most commercially successful artists in Canada. Forty years after Kurelek’s premature death, his paintings remain coveted by collectors. They represent an unconventional, unsettling, and controversial record of global anxiety in the twentieth century. Like no other artist, Kurelek twins the nostalgic and apocalyptic, his oeuvre a simultaneous vision of Eden and Hell. 3 William Kurelek Life & Work by Andrew Kear Fathers and Sons William Kurelek was born on a grain farm north of Willingdon, Alberta, to Mary (née Huculak) and Dmytro Kurelek in 1927. Mary’s parents had arrived in the region east of Edmonton around the turn of the century, in the first wave of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. These farming families, from what is known today as the Western Ukraine, transformed Canada’s harsh western prairie into a flourishing agricultural region and created an important market for the eastern manufacturing industry. The Huculaks established a homestead near Whitford Lake, then part of the Northwest Territories, in a larger Ukrainian settlement. Dmytro arrived in Canada in 1923 with the second major wave of Ukrainian immigration. -

Joyce Wieland : Life & Work

JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan 1 JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan Contents 03 Biography 12 Key Works 37 Significance & Critical Issues 47 Style & Technique 53 Where to See 59 Notes 61 Glossary 67 Sources & Resources 72 About the Author 73 Copyright & Credits 2 JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) began her career as a painter in Toronto before moving to New York in 1962, where she soon achieved renown as an experimental filmmaker. The 1960s and 1970s were productive years for Wieland, as she explored various materials and media and as her art became assertively political, engaging with nationalism, feminism, and ecology. She returned to Toronto in 1971. In 1987 the Art Gallery of Ontario held a retrospective of her work. Wieland was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1990s, and she died in 1998. 3 JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan EARLY YEARS Joyce Wieland was born in Toronto on June 30, 1930, the youngest child of Sydney Arthur Wieland and Rosetta Amelia Watson Wieland, who had emigrated from Britain. Her father’s family included several generations of acrobats and music-hall performers. Both her parents died before she reached her teens, and she and her two older siblings, Sid and Joan, experienced poverty and domestic instability as they struggled to survive. Showing an aptitude for visual expression from a young age, Wieland attended Central Technical School in Toronto, where she initially registered in a fashion design course. At this high school she learned the skills that later enabled her to work in the field of commercial design. -

M I L L I E C H E N

M I L L I E C H E N SOLO & COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITIONS 2021 “Silk Road Songbook” work-in-progress (with Arzu Ozkal), OCAT Xi’an, Xi’an, China, curators Wang Mengmeng & Karen Smith. 2019 “Matter,” Anna Kaplan Contemporary, Buffalo, NY. 2018 “Millie Chen: Four Recollections,” CU Art Museum, University of Colorado Boulder, curator Sandra Firmin. 2017 “Rock,” El Museo Francisco Oller y Diego Rivera (with Warren Quigley), Buffalo, NY, curator Bryan Lee. 2016 “Prototypes 1970s,” BT&C Gallery, Buffalo, NY. “Tour,” Project Space, Center for the Arts, University at Buffalo, curator Natalie Fleming. “PED.Toronto” (with PED collective), Koffler Art Gallery, curator Mona Filip. 2015 “Tour,” Vtape, Toronto, curators Lisa Steele & Kim Tomczak. “stain,” BT&C Gallery, Buffalo, NY. 2014 “Tour,” Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, curators Douglas Dreishpoon, Laura Brill. 2013-14 “The Miseries & Vengeance Wallpapers,” Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, curator Laura Brill. 2013 “Watcher,” echo Art Fair, Downtown Central Library, Buffalo, NY. 2012 “Ministry for Future Modification: Beijing Office” (with Warren Quigley), Where Where Art Space, Beijing, China, curators Gordon Laurin and Jing Yuan Huang. 2011 “Exquisite,” Rodman Hall Arts Centre, St. Catharines, curator Marcie Bronson. 2009 “Extreme Centre” (with Warren Quigley), Big Orbit, Buffalo, NY, curator Sean Donaher. 2008 “Extreme Centre” (with Warren Quigley), Sound Symposium, St. John’s, Newfoundland, curator Reinhard Reitzenstein. “PED.St.John’s” (with PED collective), Sound Symposium, St. John’s, Newfoundland, curator Reinhard Reitzenstein. “Watcher,” Biennale nationale de sculpture contemporaine, Trois-Rivières, Quebec, curator Josée Wingen. 2007 “Watcher,” nuit blanche: D’Arcy Street, Toronto, curator Michelle Jacques. “Demon Girl Duet Buzz Humm,” Lee Ka-sing Gallery, Toronto, curators Holly Lee & Lee Ka-sing. -

JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A

JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham 1 JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham Contents 03 Biography 09 Key Works 28 Significance & Critical Issues 33 Style & Technique 39 Where to See 44 Notes 45 Glossary 48 Sources & Resources 54 About the Author 55 Copyright & Credits 2 JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham Critically and financially, Jack Chambers was one of the most successful Canadian artists of his time. Born in London, Ontario, in 1931, he had an insatiable desire to travel and to become a professional artist. Chambers trained in Madrid in the 1950s, learning the classical traditions of Spain and Europe. He returned to London in 1961 and was integral to the city’s regionalist art movement. Chambers was diagnosed with leukemia in 1969 and died in 1978. 3 JACK CHAMBERS Life & Work by Mark A. Cheetham EARLY YEARS John Richard Chambers was born in Victoria Hospital, London, Ontario, on March 25, 1931. (He signed his name “John” until around 1970, and he is often referred to as John Chambers.) His parents, Frank R. and Beatrice (McIntyre) Chambers, came from the area. His mother’s family farmed nearby; his father was a local welder. He had one sister, Shirley, less than a year older than he was. Chambers vividly related memories of his very happy childhood in his autobiography.1 Chambers’s mother, Beatrice (née McIntyre), and his father, Frank R. Chambers. Chambers’s art education started early and well. In 1944 at Sir Adam Beck Collegiate Institute in London, he was taught by the painter Selwyn Dewdney (1909–1979), who encouraged Chambers to exhibit his early paintings. -

The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery Table of Contents

Annual Report 2012- 2013 The Power Plant exhibitions Contemporary Art Gallery 1 The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery Table of Contents “Carved out of an old red-brick building that originally housed generating equipment ... 4 President’s Report The Power Plant has instantly 5 Director’s Report 7 Exhibitions become one of Toronto’s most 14 Publications exciting and best designed 15 Education & Public Programs 29 Events art-display spaces.” 34 Members & Supporters 36 Statement of Operations - Christopher Hume, Toronto Star, 1 May 1987 “Unquestionably, The Power Plant is a valuable addition to Toronto and to Harbourfront, of which it is a kind of genius loci.” - Adele Freedman, The Globe and Mail, 2 May 1987 Photo of the construction of The Power Plant, 1987. annual report 2012-2013 3 audiences for those exhibitions, positions Throughout its 25 year history, The the public in 1987. As a result, The Power other, forming a strong community of President’s The Power Plant well for continued success. Power Plant has enjoyed the continuous Director’s Plant is enjoying increasing numbers of dedicated art enthusiasts. Report support of Harbourfront Centre. I thank Report people through its doors, and 77% of The members of the Board of Directors William Boyle and the staff of Harbour- those who visit are first-time visitors. This special year brought many changes were very proud to be engaged in the front Centre for their dedication, which is Thanks to our supporters, the gallery is to our organization. In order to meet celebrations of our 25th anniversary year, felt in many ways. -

CANADIAN IDENTITY Through the Art of GREG CURNOE Click the Right Corner to CANADIAN IDENTITY GREG CURNOE Through the Art of Return to Table of Contents

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE FOR GRADES 6–12 LEARN ABOUT CANADIAN IDENTITY through the art of GREG CURNOE Click the right corner to CANADIAN IDENTITY GREG CURNOE through the art of return to table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 RESOURCE WHO WAS TIMELINE OF OVERVIEW GREG CURNOE? HISTORICAL EVENTS AND ARTIST’S LIFE PAGE 4 PAGE 7 PAGE 10 LEARNING CULMINATING HOW GREG CURNOE ACTIVITIES TASK MADE ART: STYLE & TECHNIQUE PAGE 11 READ ONLINE DOWNLOAD ADDITIONAL GREG CURNOE: GREG CURNOE RESOURCES LIFE & WORK IMAGE FILE BY JUDITH RODGER EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE CANADIAN IDENTITY through the art of GREG CURNOE RESOURCE OVERVIEW This teacher resource guide has been written to complement the Art Canada Institute online art book Greg Curnoe: Life & Work by Judith Rodger. The artworks within this guide and the images required for the learning activities and culminating task can be found in the Greg Curnoe Image File provided. Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) was an artist from London, Ontario, who promoted his hometown as an important centre for artistic production in Canada. He began his career in the 1960s, at the beginning of a decade of change when many people asked, “What does it mean to be Canadian?” He was an ardent promoter of regionalism—a movement that looked toward one’s own life and area for inspiration—to help define Canadian identity. Curnoe expressed his passion for Canada in his paintings and his writings. He believed that there was not one single, unified Canadian identity, but rather many regional identities throughout the country. This guide explores Curnoe’s artistic practice and the formation of Canadian identity during the late twentieth century through to today. -

JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan

JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan 1 JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan Contents 03 Biography 12 Key Works 37 Significance & Critical Issues 47 Style & Technique 53 Where to See 59 Notes 61 Glossary 67 Sources & Resources 72 About the Author 73 Copyright & Credits 2 JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) began her career as a painter in Toronto before moving to New York in 1962, where she soon achieved renown as an experimental filmmaker. The 1960s and 1970s were productive years for Wieland, as she explored various materials and media and as her art became assertively political, engaging with nationalism, feminism, and ecology. She returned to Toronto in 1971. In 1987 the Art Gallery of Ontario held a retrospective of her work. Wieland was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the 1990s, and she died in 1998. 3 JOYCE WIELAND Life & Work by Johanne Sloan EARLY YEARS Joyce Wieland was born in Toronto on June 30, 1930, the youngest child of Sydney Arthur Wieland and Rosetta Amelia Watson Wieland, who had emigrated from Britain. Her father’s family included several generations of acrobats and music-hall performers. Both her parents died before she reached her teens, and she and her two older siblings, Sid and Joan, experienced poverty and domestic instability as they struggled to survive. Showing an aptitude for visual expression from a young age, Wieland attended Central Technical School in Toronto, where she initially registered in a fashion design course. At this high school she learned the skills that later enabled her to work in the field of commercial design. -

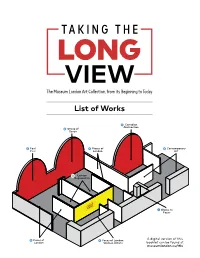

File Downloadtaking the Long View

List of Works H Canadian Abstraction E Group of Seven C Paul F Places of G Contemporary Peel London Art D London Regionalism I Works on Paper A digital version of this B Faces of A Faces of London: London Women Artists booklet can be found at museumlondon.ca/ttlv Taking the Long View is Museum London’s permanent art exhibition, featuring highlights from the vaults. It is comprised of well-loved treasures, lesser-known but intriguing gems deserving of greater attention, and recent acquisitions of modern and contemporary art. The works have been selected and arranged for ongoing viewing, and to provide our visitors with access to London’s stories. The exhibition surveys the artistic achievements of London’s artists, reflects the acumen of collectors and philanthropists, and proposes areas for future collecting and learning. Taking the Long View demonstrates the ways in which a public art collection can reflect a community. This selection gives precedence to artists living and working in this region from the mid-1800s through the 2000s. It sets their approaches and subject matter within a national context and illuminates ways in which London has always been a centre of great artistic vitality, and at times at the forefront of national innovation. Divided into thematic groupings, the exhibition has been installed in a traditional, closely arranged Salon style. Almost all of the selections are paintings, as oil and acrylic are less sensitive to light and humidity than works on paper, and so can be displayed for longer periods of time. Sections include Faces, which involves portraits by London painters. -

Winter 2017 January - April EXHIBITIONS 3

Winter 2017 January - April EXHIBITIONS 3 John Boyle (Canadian, b. 1941), Dance (detail), 1995, watercolour on paper, Brian Jones (Canadian, 1950-2008), The Big Remco Whirlybird in the House (detail), 2007, Collection of Museum London, Gift of Jeffrey Lipson, Toronto, 2002 oil on canvas, Private Collection, Toronto, Ontario Canadian Eh? Brian Jones: The Sun Shines in All Yards A History of the Nation’s Signs and Symbols January 28 to May 7, 2017 Moore & Volunteer Galleries January 7 to May 7, 2017 Interior Gallery Opening Reception: Sunday, February 5 at 1:00 pm Opening Reception: Sunday, February 5 at 1:00 pm The exhibition documents the work of artist Brian Jones, representing his meticulous technique and inventive imagery through selected drawings, prints, oil, and watercolour What symbols make you think of Canada? Perhaps it’s the Canadian flag or the beaver? Or paintings. maybe it’s the game of hockey or lacrosse? These are just some of the many symbols that have come to represent the nation in popular culture. They help to communicate our history Jones’ practice encompasses early figurative works and landscapes inspired by the look of and our culture, and to establish our distinct national identity. But there are many unofficial family photographs and youthful memories; investigations of dramatic light and shape; and symbols that do the same thing. For some it’s our varied landscape and climate, or foods a long-running, lyrical ode to suburban North American family life. Over the course of his such as poutine or maple syrup. For others, it’s the values enshrined in our Charter of Rights career, Jones developed two concurrent styles for which he garnered acclaim: one highly and Freedoms.