Community Streetscape Markers: Context Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Fy2021 Moving to Work Annual Plan

PROPOSED FY2021 MOVING TO WORK ANNUAL PLAN Submitted to HUD on October 16, 2020 2 Table of Contents Section I: Introduction ............................................................................................................ 3 Section II: General Operating Information .............................................................................. 9 Section IIA: Housing Stock Information .................................................................................................. 9 i. Planned New Public Housing Units in FY2021 .......................................................................... 9 ii. Planned Public Housing Units to be Removed in FY2021 ........................................................ 9 iii. Planned New Project-Based Vouchers in FY2021 ................................................................... 10 iv. Planned Existing Project-Based Vouchers ............................................................................... 11 v. Planned Other Changes to the Housing Stock in FY2021 ...................................................... 21 vi. General Description of Planned Capital Expenditures in FY2021 ......................................... 27 Section II-B: Leasing Information .......................................................................................................... 27 i. Planned Number of MTW Households Served at the End of FY2021 .................................... 27 ii. Description of Anticipated Issues Related to Leasing in FY2021 ......................................... -

Housing Report

Strengthening the Puerto Rican and Latino Presence in Chicago May 14, 2019 !1 Suggested Citation: García, I. et al. 2019. “Strengthening the Puerto Rican and Latino Presence in Chicago.” The Puerto Rican Agenda. http://www.puertoricanchicago.org/. Puerto Rican Agenda Team: José E. López, Puerto Rican Cultural Center Ruben D. Feliciano, Puerto Rican Cultural Center Joy Aruguete, Chief Executive Officer, Bickerdike Redevelopment Corp. Guacolda Reyes, Vice President, Bickerdike Redevelopment Corp. Juan Carlos Linares, Executive Director, LUCHA Hipolito Roldan, President of Hispanic Housing Development Corp. Eliud Medina, Chair of Puerto Rican Agenda Housing Committee ChicagoLAB Team: Ivis García, Assistant Professor, University of Utah Alexander Jay Jacobs Anders Rauk Bryan Luu Jimmie Carroll Gray Logan Langston Hunt Lauren McKenzie Victor Michael John Baker Samah Sufia Safiullah Sponsors: Wintrust LISC Chicago Liberty Bank MB Financial Bank PNC Bank Polk Bros Foundation !2 Suggested Citation: García, I. et al. 2019. “Strengthening the Puerto Rican and Latino Presence in Chicago.” The Puerto Rican Agenda. http://www.puertoricanchicago.org/. Table of Contents Introduction 4 Team 6 Guiding Principles 7 Vision and Goals 8 Community Timeline 9 Demographic Analysis 10 Four Key Policies 27 General Recommendations 33 “Division Street,” the Paseo Boricua, “must be the most beautifully decorated street in America. And since you have the prettiest street in America, it’s possible that you may just be at the forefront of this [displacement] struggle for the whole United States, and then maybe for the whole world. As you lift up your voices, you teach all of us what we are supposed to do to make progress.” - Dr. -

The Second Public Meeting for the North Milwaukee Ave from Logan Square to Belmont Study

Public Meeting #2 January 30, 2018 Welcome to the second Public Meeting for the North Milwaukee Ave from Logan Square to Belmont study. Your participation in tonight's meeting will help shape future improvements to North Milwaukee Ave and Logan Square. We appreciate your involvement and look forward to your continued participation throughout the study. 1 PROJECT OVERVIEW From the Spring of 2017 through Summer 2018, CDOT will be working with community members to identify traffic and safety improvements that will make Milwaukee Avenue from West Logan Boulevard to Belmont Avenue more user-friendly. From the Spring of 2017 through Summer 2018, CDOT will be working with community members to identify traffic and safety improvements that will make Milwaukee Avenue from West Logan Boulevard to Belmont Avenue more user-friendly. 2 PROJECT OVERVIEW This includes potential updates to Logan Square, building off the Logan Square Bicentennial Improvements Project. We will seek to maintain the Square’s historic integrity while balancing the needs of the area’s diverse residents, businesses, and commuters. This includes potential updates to Logan Square, building off the Logan Square Bicentennial Improvements Project. We will seek to maintain the Square’s historic integrity while balancing the needs of the area’s diverse residents, businesses, and commuters. 3 Study Area Belmont Ave Kedzie Ave Kedzie Logan Blvd The study area is located along Milwaukee Ave from Belmont on the northwest to the Logan Square intersection on the southeast. 4 Study Goals North Milwaukee Avenue is a local and regional street for multiple modes of transportation. It is officially zoned and functions as a Pedestrian Street from Diversey to Logan. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

The History of the City of Chicago Flag

7984 S. South Chicago Ave. - Chicago, IL 60616 Ph: 773-768-8076 Fx: 773-768-3138 www.wgnflag.com The History of the City of Chicago Flag In 1915, Alderman James A Kearns proposed to the city council that Chicago should have a flag. Council approved the proposal and established the Chicago Flag Commission to consider designs for the flag. A contest was held and a prize offered for the winning design. The competition was won by Mr. Wallace Rice, author and editor, who had been interested in flags since his boyhood. It took Mr. Rice no less than six weeks to find a suitable combination of color, form, and symbolism. Mr. Rice’s design was approved by the city council in the summer of 1917. Except for the addition of two new stars—one in 1933 commemorating “the Century of Progress” and one in 1939 commemorating Fort Dearborn—the flag remains unchanged to this day. In explaining some of the symbolism of his flag design, Mr. Rice says: It is white, the composite of all colors, because its population is a composite of all nations, dwelling here in peace. The white is divided into three parts—the uppermost signifying the north side, the larger middle area the great west side with an area and population almost exceeding that of the other two sides, and the lowermost, the south side. The two stripes of blue signify, primarily, Lake Michigan and the north Chicago River above, bounding the north side and south branch of the river and the great canal below. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Collection Overview

Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 Collection Overview The Gerber/Hart archives focuses its collections on gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer life in the Chicago metropolitan area and the Midwest. It contains over 150 collections of historically significant personal manuscripts, photographs, audiovisual recordings, and organizational records. These collections include unpublished material such as letters, diaries, and scrapbooks documenting the lives of both average people and community leaders. They also include the records of many community organizations, businesses, and political campaigns. This guide is intended to serve as a preliminary research tool that provides a brief description of holdings with basic information on size, inclusive dates, types of records, and broad subject areas. Guide Contents List of Collections..............................................................................................................................................2 Collections Descriptions....................................................................................................................................6 Name Index......................................................................................................................................................26 Topical Index...................................................................................................................................................34 1 Archives Collections Guide Updated March 28, 2016 List of Collections -

Humboldt Park Mural Tour

Humboldt Park Mural Tour Murals occupy a prominent place in Chicago’s landscape. They reveal the unique meaning and character of a community and can include a narrative or history. This brochure highlights selected murals in Humboldt Park with a suggested route for a self-guided walking or biking tour. Each letter on the map corresponds to a brief description of the mural. This tour promotes exercise and the 5-4-3-2-1 Go! message described on the back panel. Remember to bring water and stay hydrated. We hope you enjoy your tour! Mural Tour Map ˆN La Crucifixion de Don Pedro Albizu Campos, 1971 Mario Galan, Jose Bermudez, Hector Rosario 2425 West North Ave. • Don Pedro Albizu Campos, the leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, is depicted crucified in the cen- ter alongside two other Nationalists of the 1950s. Portraits of six independence and abolitionist leaders of the 19th century are lined across the top. • The flag in the background is called the La Bandera de Lares. It represents Puerto Rico’s first declaration of independence from Spain on September 23, 1868. This armed uprising is known as El Grito de Lares. • It took nine years to save this mural from destruction. A new condominium was planned and if built, would have blocked off the mural. Community members concerned about gentrification of the neighborhood as well as saving the oldest Puerto Rican mural in Chicago went into action and saved it. I Will… The People United Cannot Be Defeated, 2004 Northeastern Illinois University Students 1300 North Western Ave. -

The Great Chicago Fire

rd 3 Grade Social Sciences ILS—16A, 16C, 16D, 17A The Great Chicago Fire How did the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871 change the way people designed and constructed buildings in the city? Vocabulary This lesson assumes that students already know the basic facts about the Chicago Fire. The lesson is designed to help students think about what happened after the load-bearing method a method of fire died out and Chicagoans started to rebuild their city. construction where bricks that form the walls support the structure Theme skeleton frame system a method This lesson helps students investigate how the fire resulted in a change of the of construction where a steel frame construction methods and materials of buildings. By reading first-hand accounts, acts like the building’s skeleton to support the weight of the structure, using historic photographs, and constructing models, students will see how the and bricks or other materials form the people of Chicago rebuilt their city. building’s skin or outer covering story floors or levels of a building Student Objectives • write from the point of view of a person seen in photographs taken shortly after conflagration a large destructive fire the Great Chicago Fire • point of view trying to imagine distinguish between fact and opinion Grade Social Sciences how another person might see or rd • differentiate between a primary source and a secondary source 3 understand something • discover and discuss the limitations and potential of load-bearing and skeleton frame construction methods primary source actual -

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 Update II August 18, 2014

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 update II August 18, 2014 Dear Friends, The Streeterville Neighborhood Plan (“SNP”) was originally written in 2005 as a community plan written by a Chicago community group, SOAR, the Streeterville Organization of Active Resi- dents. SOAR was incorporated on May 28, 1975. Throughout our history, the organization has been a strong voice for conserving the historic character of the area and for development that enables divergent interests to live in harmony. SOAR’s mission is “To work on behalf of the residents of Streeterville by preserving, promoting and enhancing the quality of life and community.” SOAR’s vision is to see Streeterville as a unique, vibrant, beautiful neighborhood. In the past decade, since the initial SNP, there has been significant development throughout the neighborhood. Streeterville’s population has grown by 50% along with new hotels, restaurants, entertainment and institutional buildings creating a mix of uses no other neighborhood enjoys. The balance of all these uses is key to keeping the quality of life the highest possible. Each com- ponent is important and none should dominate the others. The impetus to revising the SNP is the City of Chicago’s many new initiatives, ideas and plans that SOAR wanted to incorporate into our planning document. From “The Pedestrian Plan for the City”, to “Chicago Forward”, to “Make Way for People” to “The Redevelopment of Lake Shore Drive” along with others, the City has changed its thinking of the downtown urban envi- ronment. If we support and include many of these plans into our SNP we feel that there is great- er potential for accomplishing them together. -

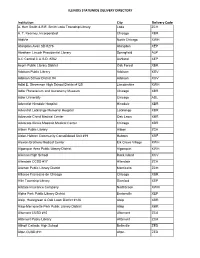

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

107Th Congress 83

ILLINOIS 107th Congress 83 National Alliance, Chicago Historical Society; 23rd Ward Democratic Committeeman, 1974– present; married: the former Rose Marie Lapinski, 1962; children: Laura and Dan; award: Man of the Year, Area 4, Chicago Park District, January 1983; committee: Transportation and Infra- structure; subcommittees: Aviation (ranking member); Highways and Transit; Railroads; elected on November 2, 1982, to the 98th Congress; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings 2470 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ................................. (202) 225–5701 Chief of Staff.—Colleen Corr. FAX: 225–1012 Legislative Director.—Michael McLaughlin. Senior Policy Advisor.—Jason Tai. Executive Assistant.—Jennifer Murer. Legislative Assistants: Ashley Musselman, Ryan Quinn. 5832 South Archer Avenue, Chicago, IL 60638 ......................................................... (312) 886–0481 District Director.—Jerry Hurckes. District Scheduler.—Elaine McCarthy. 5239 W. 95th Street, Oak Lawn, IL 60453 ................................................................. (708) 952–0860 Staff Assistant.—Lenore Goodfriend. 19 W. Hillgrove, LaGrange, IL 60525 ......................................................................... (708) 352–0725 Staff Assistant.—Rita Pula. County: COOK COUNTY (part); cities and townships of Alsip, Argo, Bedford Park, Berwyn, Bridgeview, Burr Ridge, Chicago, Chicago Ridge, Cicero, Countryside, Crestwood Midlothian, Forest Park, Hickory Hills, Hinsdale, Hometown, Hodgkins, Indian Head Park,