Synthetic Biology Within the Operon Model and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B

Transformations of Lamarckism Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology Gerd B. M ü ller, G ü nter P. Wagner, and Werner Callebaut, editors The Evolution of Cognition , edited by Cecilia Heyes and Ludwig Huber, 2000 Origination of Organismal Form: Beyond the Gene in Development and Evolutionary Biology , edited by Gerd B. M ü ller and Stuart A. Newman, 2003 Environment, Development, and Evolution: Toward a Synthesis , edited by Brian K. Hall, Roy D. Pearson, and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2004 Evolution of Communication Systems: A Comparative Approach , edited by D. Kimbrough Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2004 Modularity: Understanding the Development and Evolution of Natural Complex Systems , edited by Werner Callebaut and Diego Rasskin-Gutman, 2005 Compositional Evolution: The Impact of Sex, Symbiosis, and Modularity on the Gradualist Framework of Evolution , by Richard A. Watson, 2006 Biological Emergences: Evolution by Natural Experiment , by Robert G. B. Reid, 2007 Modeling Biology: Structure, Behaviors, Evolution , edited by Manfred D. Laubichler and Gerd B. M ü ller, 2007 Evolution of Communicative Flexibility: Complexity, Creativity, and Adaptability in Human and Animal Communication , edited by Kimbrough D. Oller and Ulrike Griebel, 2008 Functions in Biological and Artifi cial Worlds: Comparative Philosophical Perspectives , edited by Ulrich Krohs and Peter Kroes, 2009 Cognitive Biology: Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives on Mind, Brain, and Behavior , edited by Luca Tommasi, Mary A. Peterson, and Lynn Nadel, 2009 Innovation in Cultural Systems: Contributions from Evolutionary Anthropology , edited by Michael J. O ’ Brien and Stephen J. Shennan, 2010 The Major Transitions in Evolution Revisited , edited by Brett Calcott and Kim Sterelny, 2011 Transformations of Lamarckism: From Subtle Fluids to Molecular Biology , edited by Snait B. -

Ecological Developmental Biology and Disease States CHAPTER 5 Teratogenesis: Environmental Assaults on Development 167

Integrating Epigenetics, Medicine, and Evolution Scott F. Gilbert David Epel Swarthmore College Hopkins Marine Station, Stanford University Sinauer Associates, Inc. • Publishers Sunderland, Massachusetts U.S.A. © Sinauer Associates, Inc. This material cannot be copied, reproduced, manufactured or disseminated in any form without express written permission from the publisher. Brief Contents PART 1 Environmental Signals and Normal Development CHAPTER 1 The Environment as a Normal Agent in Producing Phenotypes 3 CHAPTER 2 How Agents in the Environment Effect Molecular Changes in Development 37 CHAPTER 3 Developmental Symbiosis: Co-Development as a Strategy for Life 79 CHAPTER 4 Embryonic Defenses: Survival in a Hostile World 119 PART 2 Ecological Developmental Biology and Disease States CHAPTER 5 Teratogenesis: Environmental Assaults on Development 167 CHAPTER 6 Endocrine Disruptors 197 CHAPTER 7 The Epigenetic Origin of Adult Diseases 245 PART 3 Toward a Developmental Evolutionary Synthesis CHAPTER 8 The Modern Synthesis: Natural Selection of Allelic Variation 289 CHAPTER 9 Evolution through Developmental Regulatory Genes 323 CHAPTER 10 Environment, Development, and Evolution: Toward a New Synthesis 369 CODA Philosophical Concerns Raised by Ecological Developmental Biology 403 APPENDIX A Lysenko, Kammerer, and the Truncated Tradition of Ecological Developmental Biology 421 APPENDIX B The Molecular Mechanisms of Epigenetic Change 433 APPENDIX C Writing Development Out of the Modern Synthesis 441 APPENDIX D Epigenetic Inheritance Systems: -

Early-Life Experience, Epigenetics, and the Developing Brain

Neuropsychopharmacology REVIEWS (2015) 40, 141–153 & 2015 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/15 REVIEW ............................................................................................................................................................... www.neuropsychopharmacologyreviews.org 141 Early-Life Experience, Epigenetics, and the Developing Brain 1 ,1 Marija Kundakovic and Frances A Champagne* 1Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA Development is a dynamic process that involves interplay between genes and the environment. In mammals, the quality of the postnatal environment is shaped by parent–offspring interactions that promote growth and survival and can lead to divergent developmental trajectories with implications for later-life neurobiological and behavioral characteristics. Emerging evidence suggests that epigenetic factors (ie, DNA methylation, posttranslational histone modifications, and small non- coding RNAs) may have a critical role in these parental care effects. Although this evidence is drawn primarily from rodent studies, there is increasing support for these effects in humans. Through these molecular mechanisms, variation in risk of psychopathology may emerge, particularly as a consequence of early-life neglect and abuse. Here we will highlight evidence of dynamic epigenetic changes in the developing brain in response to variation in the quality of postnatal parent–offspring interactions. The recruitment of epigenetic pathways for the -

The Life-Cycle of Operons

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Title The Life-cycle of Operons Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0sx114h9 Authors Price, Morgan N. Arkin, Adam P. Alm, Eric J. Publication Date 2005-11-18 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Title: The Life-cycle of Operons Authors: Morgan N. Price, Adam P. Arkin, and Eric J. Alm Author a±liation: Lawrence Berkeley Lab, Berkeley CA, USA and the Virtual Institute for Microbial Stress and Survival. A.P.A. is also a±liated with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the UC Berkeley Dept. of Bioengineering. Corresponding author: Eric Alm, [email protected], phone 510-486-6899, fax 510-486-6219, address Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, 1 Cyclotron Road, Mailstop 977-152, Berkeley, CA 94720 Abstract: Operons are a major feature of all prokaryotic genomes, but how and why operon structures vary is not well understood. To elucidate the life-cycle of operons, we compared gene order between Escherichia coli K12 and its relatives and identi¯ed the recently formed and destroyed operons in E. coli. This allowed us to determine how operons form, how they become closely spaced, and how they die. Our ¯ndings suggest that operon evolution is driven by selection on gene expression patterns. First, both operon creation and operon destruction lead to large changes in gene expression patterns. For example, the removal of lysA and ruvA from ancestral operons that contained essential genes allowed their expression to respond to lysine levels and DNA damage, respectively. Second, some operons have undergone accelerated evolution, with multiple new genes being added during a brief period. -

From 1957 to Nowadays: a Brief History of Epigenetics

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review From 1957 to Nowadays: A Brief History of Epigenetics Paul Peixoto 1,2, Pierre-François Cartron 3,4,5,6,7,8, Aurélien A. Serandour 3,4,6,7,8 and Eric Hervouet 1,2,9,* 1 Univ. Bourgogne Franche-Comté, INSERM, EFS BFC, UMR1098, Interactions Hôte-Greffon-Tumeur/Ingénierie Cellulaire et Génique, F-25000 Besançon, France; [email protected] 2 EPIGENEXP Platform, Univ. Bourgogne Franche-Comté, F-25000 Besançon, France 3 CRCINA, INSERM, Université de Nantes, 44000 Nantes, France; [email protected] (P.-F.C.); [email protected] (A.A.S.) 4 Equipe Apoptose et Progression Tumorale, LaBCT, Institut de Cancérologie de l’Ouest, 44805 Saint Herblain, France 5 Cancéropole Grand-Ouest, Réseau Niches et Epigénétique des Tumeurs (NET), 44000 Nantes, France 6 EpiSAVMEN Network (Région Pays de la Loire), 44000 Nantes, France 7 LabEX IGO, Université de Nantes, 44000 Nantes, France 8 Ecole Centrale Nantes, 44300 Nantes, France 9 DImaCell Platform, Univ. Bourgogne Franche-Comté, F-25000 Besançon, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 September 2020; Accepted: 13 October 2020; Published: 14 October 2020 Abstract: Due to the spectacular number of studies focusing on epigenetics in the last few decades, and particularly for the last few years, the availability of a chronology of epigenetics appears essential. Indeed, our review places epigenetic events and the identification of the main epigenetic writers, readers and erasers on a historic scale. This review helps to understand the increasing knowledge in molecular and cellular biology, the development of new biochemical techniques and advances in epigenetics and, more importantly, the roles played by epigenetics in many physiological and pathological situations. -

Epigenetics Analysis and Integrated Analysis of Multiomics Data, Including Epigenetic Data, Using Artificial Intelligence in the Era of Precision Medicine

biomolecules Review Epigenetics Analysis and Integrated Analysis of Multiomics Data, Including Epigenetic Data, Using Artificial Intelligence in the Era of Precision Medicine Ryuji Hamamoto 1,2,*, Masaaki Komatsu 1,2, Ken Takasawa 1,2 , Ken Asada 1,2 and Syuzo Kaneko 1 1 Division of Molecular Modification and Cancer Biology, National Cancer Center Research Institute, 5-1-1 Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan; [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (K.A.); [email protected] (S.K.) 2 Cancer Translational Research Team, RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project, 1-4-1 Nihonbashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0027, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-3-3547-5271 Received: 1 December 2019; Accepted: 27 December 2019; Published: 30 December 2019 Abstract: To clarify the mechanisms of diseases, such as cancer, studies analyzing genetic mutations have been actively conducted for a long time, and a large number of achievements have already been reported. Indeed, genomic medicine is considered the core discipline of precision medicine, and currently, the clinical application of cutting-edge genomic medicine aimed at improving the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of diseases is promoted. However, although the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003 and large-scale genetic analyses have since been accomplished worldwide with the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS), explaining the mechanism of disease onset only using genetic variation has been recognized as difficult. Meanwhile, the importance of epigenetics, which describes inheritance by mechanisms other than the genomic DNA sequence, has recently attracted attention, and, in particular, many studies have reported the involvement of epigenetic deregulation in human cancer. -

Epigenetics: the Biochemistry of DNA Beyond the Central Dogma

Epigenetics: The Biochemistry of DNA Beyond the Central Dogma Since the Human Genome Project was completed, the newly emerging field of epigenetics is providing a basis for understanding how heritable changes, other than those in the DNA sequence, can influence phenotypic variation. Epigenetics, essentially, affects how genes are read by cells and subsequently how they produce proteins. The interest in epigenetics has led to new findings about the relationship between epigenetic changes and a host of disorders including cancer, immune disorders, and neuropsychiatric disorders. The field of epigenetics is quickly growing and with it the understanding that both the environment and lifestyle choices can directly interact with the genome to influence epigenetic change. This unit is designed to provide a detailed look at the influence of epigenetics on gene expression through developmental stages, tissue-specific needs, and environmental impacts. Students will complete this unit with the understanding that gene regulation and expression is truly “above the genome” and well beyond the simplified mechanism of the Central Dogma of Biology. University of Florida Center for Precollegiate Education and Training www.cpet.ufl.edu 1 EPIGENETICS: THE BIOCHEMISTRY OF DNA www.cpet.ufl.edu 2 Author: Susan Chabot This curriculum was developed as part of Biomedical Explorations: Bench to Bedside, which is supported by the Office Of The Director, National Institutes Of Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25 OD016551. The content -

Epigenetics for Dummies

On reflection Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-133993 on 25 February 2016. Downloaded from fur instead of brown. In another much Epigenetics for dummies quoted experiment, researchers claimed to show that mice bred from fathers who John Launer had been trained to become afraid of a particular smell also showed avoidance of the same smell – although it is hard to In the last few years, epigenetics has mechanisms themselves are very common understand how such a specific outcome seized the public imagination. Magazines in nature, quite aside from environmental could be achieved through known New Scientist fl like are publishing articles in uences, and they govern gene expres- molecular mechanisms.9 “ with titles such as How to change your sion in all kinds of ways, including As far as human beings are concerned, ” 1 genes by changing your lifestyle . A turning a stem cell into a liver or a skin everyone has known for a long time that book called “The Epigenetic Revolution” cell, or a bee larva into a worker or a 2 maternal behaviour during pregnancy has become a bestseller. The popular queen bee. One hypomethylating agent, affects the growing fetus, with lifelong press regularly reports epigenetic research, decitabine, is an established treatment for effects. The most familiar example is including a recent study purporting to myelodysplastic disorders. probably foetal alcohol syndrome, where show that severe psychological trauma can The question then arises: do environ- a mother’s addiction can lead to irrepar- ’ 3 be passed down through one s genes. mental effects have to happen anew in able damage to her infant. -

GENE REGULATION Differences Between Prokaryotes & Eukaryotes

GENE REGULATION Differences between prokaryotes & eukaryotes Gene function Description of Prokaryotic Chromosome and E.coli Review Differences between Prokaryotic & Eukaryotic Chromosomes Four differences Eukaryotic Chromosomes Form Length in single human chromosome Length in single diploid cell Proteins beside histones Proportion of DNA that codes for protein in prokaryotes eukaryotes humans Regulation of Gene Expression in Prokaryotes Terms promoter structural gene operator operon regulator repressor corepressor inducer The lac operon - Background E.coli behavior presence of lactose and absence of lactose behavior of mutants outcome of mutants The Lac operon Regulates production of b-galactosidase http://www.sumanasinc.com/webcontent/animations/content/lacoperon.html The trp operon Regulates the production of the enzyme for tryptophan synthesis http://bcs.whfreeman.com/thelifewire/content/chp13/1302002.html General Summary During transcription, RNA remains briefly bound to the DNA template Structural genes coding for polypeptides with related functions often occur in sequence Two kinds of regulatory control positive & negative General Summary Regulatory efficiency is increased because mRNA is translated into protein immediately and broken down rapidly. 75 different operons comprising 260 structural genes in E.coli Gene Regulation in Eukaryotes some regulation occurs because as little as one % of DNA is expressed Gene Expression and Differentiation Characteristic proteins are produced at different stages of differentiation producing cells with their own characteristic structure and function. Therefore not all genes are expressed at the same time As differentiation proceeds, some genes are permanently “turned” off. Example - different types of hemoglobin are produced during development and in adults. DNA is expressed at a precise time and sequence in time. -

Epigenetics and the Biological Definition of Gene × Environment

Child Development, January/February 2010, Volume 81, Number 1, Pages 41–79 Epigenetics and the Biological Definition of Gene · Environment Interactions Michael J. Meaney McGill University Variations in phenotype reflect the influence of environmental conditions during development on cellular functions, including that of the genome. The recent integration of epigenetics into developmental psychobiol- ogy illustrates the processes by which environmental conditions in early life structurally alter DNA, provid- ing a physical basis for the influence of the perinatal environmental signals on phenotype over the life of the individual. This review focuses on the enduring effects of naturally occurring variations in maternal care on gene expression and phenotype to provide an example of environmentally driven plasticity at the level of the DNA, revealing the interdependence of gene and environmental in the regulation of phenotype. The nature–nurture debate is essentially a question prevention and intervention programs. In the social of the determinants of individual differences in the sciences, and particularly psychology, there has expression of specific traits among members of the generally been an understandable bias in favor of same species. The origin of the terms nature and explanations derived from the ‘‘nurture’’ perspec- nurture has been credited to Richard Mulcaster, a tive, which emphasizes the capacity for environ- British teacher who imagined these influences as mentally induced plasticity in brain structure and collaborative forces that shape child development function. Nevertheless, over recent decades there (West & King, 1987). History has conspired to per- has been a gradual, if at times reluctant acceptance vert Mulcaster’s intent, casting genetic and environ- that genomic variations contribute to individual dif- mental influences as independent agents in the ferences in brain development and function. -

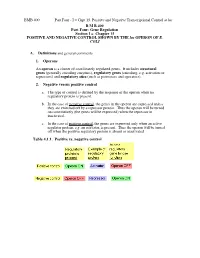

I = Chpt 15. Positive and Negative Transcriptional Control at Lac BMB

BMB 400 Part Four - I = Chpt 15. Positive and Negative Transcriptional Control at lac B M B 400 Part Four: Gene Regulation Section I = Chapter 15 POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE CONTROL SHOWN BY THE lac OPERON OF E. COLI A. Definitions and general comments 1. Operons An operon is a cluster of coordinately regulated genes. It includes structural genes (generally encoding enzymes), regulatory genes (encoding, e.g. activators or repressors) and regulatory sites (such as promoters and operators). 2. Negative versus positive control a. The type of control is defined by the response of the operon when no regulatory protein is present. b. In the case of negative control, the genes in the operon are expressed unless they are switched off by a repressor protein. Thus the operon will be turned on constitutively (the genes will be expressed) when the repressor in inactivated. c. In the case of positive control, the genes are expressed only when an active regulator protein, e.g. an activator, is present. Thus the operon will be turned off when the positive regulatory protein is absent or inactivated. Table 4.1.1. Positive vs. negative control BMB 400 Part Four - I = Chpt 15. Positive and Negative Transcriptional Control at lac 3. Catabolic versus biosynthetic operons a. Catabolic pathways catalyze the breakdown of nutrients (the substrate for the pathway) to generate energy, or more precisely ATP, the energy currency of the cell. In the absence of the substrate, there is no reason for the catabolic enzymes to be present, and the operon encoding them is repressed. In the presence of the substrate, when the enzymes are needed, the operon is induced or de-repressed. -

Escherichia Coli (Gene Fusion/Attenuator/Terminator/RNA Polymerase/Ribosomal Proteins) GERARD BARRY, CATHERINE L

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 76, No. 10, pp. 4922-4926, October 1979 Biochemistry Control features within the rplJL-rpoBC transcription unit of Escherichia coli (gene fusion/attenuator/terminator/RNA polymerase/ribosomal proteins) GERARD BARRY, CATHERINE L. SQUIRES, AND CRAIG SQUIRES Department of Biological Sciences, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027 Communicated by Cyrus Levinthal, July 2, 1979 ABSTRACT Gene fusions constructed in vitro have been regulation could occur (4-7). Yet under certain conditions, used to examine transcription regulatory signals from the operon coordinate of the RNA which encodes ribosomal proteins L10 and L7/12 and the RNA expression polymerase subunits and polymerase P and #I subunits (the rplJL-rpoBC operon). Por- ribosomal proteins is not observed. This is especially true of the tions of this operon, which were obtained by in vitro deletions, rplJL-rpoBC transcription unit which encodes the ribosomal have been placed between the ara promoter and the lacZgene proteins L10 and L7/12 and the RNA polymerase subunits 13 in the gene-fusion plasmid pMC81 developed by M. Casadaban and 13'. For example, only the ribosomal proteins are modulated and S. Cohen. The effect of the inserted DNA segment on the by the stringent regulation system (8, 9) whereas a transient expression of the IacZ gene (in the presence and absence of arabinose) permits the localization of regulatory signals to dis- stimulatory effect of rifampicin is specific for the RNA poly- crete regions of the rpIJL-rpoBC operon. An element that re- merase subunits (10, 11). In addition, different amounts of duces the level of distal gene expression to one-sixth is located mRNA hybridize to the rpl and rpo regions of the rplJL-rpoBC on a fragment which spans the rplL-rpoB intercistronic region.