Start2quit : a Randomised Clinical Controlled Trial to Evaluate The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selfies As Charitable Meme : Charity and National Identity in the #Nomakeupselfie and #Thumbsupforstephen Campaigns DELLER, Ruth A

Selfies as charitable meme : charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and #thumbsupforstephen campaigns DELLER, Ruth A. <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4935-980X> and TILTON, Shane Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/10097/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version DELLER, Ruth A. and TILTON, Shane (2015). Selfies as charitable meme : charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International Journal of Communication, 9 (5), 1788-1805. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk International Journal of Communication 9(2015), Feature 1–20 1932–8036/2015FEA0002 Selfies as Charitable Meme: Charity and National Identity in the #nomakeupselfie and #thumbsupforstephen Campaigns RUTH A. DELLER Sheffield Hallam University, UK SHANE TILTON Ohio Northern University, USA Keywords: selfies, social media, charity, identity, gender In March 2014, a viral campaign spread across social media using the tag #nomakeupselfie. This campaign involved women posting selfies without wearing makeup and (in later iterations of the trend) donating money to cancer charities. It was credited with raising £8 million for the charity Cancer Research UK (CRUK) and received a wealth of coverage in mainstream news media as well as across a range of blogs and news sites. The starting point for the #nomakeupselfie has been attributed by its lead campaigner to a single picture Laura Lippman posted on Twitter after Kim Novak’s appearance at the Oscars on 2nd March 2014 (Ciambriello, 2014; London, 2014).1 Novak’s appearance was marred by criticism about her look. -

Selfies As Charitable Meme: Charity and National Identity in the #Nomakeupselfie and #Thumbsupforstephen Campaigns

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), Feature 1788–1805 1932–8036/2015FEA0002 Selfies as Charitable Meme: Charity and National Identity in the #nomakeupselfie and #thumbsupforstephen Campaigns RUTH A. DELLER Sheffield Hallam University, UK SHANE TILTON Ohio Northern University, USA Keywords: selfies, social media, charity, identity, gender In March 2014, a viral campaign spread across social media using the tag #nomakeupselfie. This campaign involved women posting selfies without wearing makeup and (in later iterations of the trend) donating money to cancer charities. It was credited with raising £8 million for the charity Cancer Research UK (CRUK) and received a wealth of coverage in mainstream news media as well as across a range of blogs and news sites. The starting point for the #nomakeupselfie has been attributed by its lead campaigner to a single picture Laura Lippman posted on Twitter after Kim Novak’s appearance at the Oscars on 2nd March 2014 (Ciambriello, 2014; London, 2014).1 Novak’s appearance was marred by criticism about her look. Some people on Twitter commented on how her face was not beautiful and that it was disfigured from plastic surgery. Lippman’s tweet of “No makeup, kind lighting. #itsokkimnovak” (Figure 1) was noted as the starting point to the prosocial focus of this hashtag. The meme2 initially saw female users of multiple social media sites post selfies sans makeup with comments along the lines of “here’s my makeup-free selfie for breast cancer.” Before long, the posts mutated to being about cancer more generally, and they acquired messages with more specific actions, such as “Text BEAT to 70099 to donate £3.” More people started to share these photos, sometimes accompanied by a screenshot of their mobile phone to prove they had donated. -

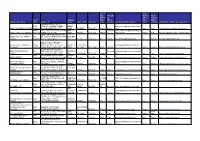

Grid Export Data

Accoun Chief ting Accounti Finance Chief Officer ng Officer Finance Trust Address First Officer First Officer Organisation Name. Type Address 1 Line 2 Town / City Postcode name Surname Accounting Officer Email Name Surname Chief Finance Officer Email Address BOURNE ABBEY C OF E Multi PRIMARY ACADEMY ABBEY ABBEY [email protected] ABBEY ACADEMIES TRUST Academy ROAD BOURNE PE10 9EP ROAD BOURNE PE10 9EP Sarah Moore ch.uk Jane King [email protected] Single ABBEY COLLEGE ABBEY ROAD ABBEY Christofor [email protected] ABBEY COLLEGE, RAMSEY Academy RAMSEY PE26 1DG ROAD RAMSEY PE26 1DG Andrew ou ambs.sch.uk Robert Heal [email protected] ABBEY GRANGE CHURCH OF ABBEY MULTI ACADEMY Multi ENGLAND ACADEMY BUTCHER BUTCHER TRUST Academy HILL LEEDS LS16 5EA HILL LEEDS LS16 5EA Ian Harmer [email protected] Ian Harmer [email protected] ABBOTS HALL PRIMARY ABBOTS HALL PRIMARY Single ACADEMY ABBOTTS DRIVE ABBOTTS STANFORD- [email protected] ACADEMY Academy STANFORD-LE-HOPE SS17 7BW DRIVE LE-HOPE SS17 7BW Laura Fishleigh k Joanne Forkner [email protected] RUSH COMMON SCHOOL ABINGDON LEARNING Multi HENDRED WAY ABINGDON, HENDRED Stevenso headteacher@rushcommonschool. TRUST Academy OXFORDSHIRE OX14 2AW WAY ABINGDON OX14 2AW Jacquie n org Zoe Bratt [email protected] Multi The Kingsway School Foxland Foxland ABNEY TRUST Academy Road Cheadle Cheshire SK8 4QX Road Cheshire SK8 4QX Jo Lowe [email protected] James Dunbar [email protected] -

Inside This Issue

Connect The newsletter for West Brom members Winter 2017 Inside this issue Attitudes to saving Awards success Staying safe online St Giles Walsall Hospice Supporting Teenage Cancer Trust Thumbs up for Stephen’s Story New Birmingham branch We’re still a nation of savers Britons haven’t lost their appetite for saving, according to a survey “People have a strong conducted by the West Brom. grip on their finances Even as the pound fluctuates amid concerns and regularly review over Brexit and interest rates sit at record their financial position.” lows, most people still want to entrust their money to a bank or building society. account, showing a willingness to consider Out of the 1,300 adults questioned, including West investing money in alternative ways. Brom customers*, 72 per cent classed themselves as regular savers. Some 69 per cent expected to A third were prepared to look at investing in save the same amount of money in the next 12 stocks and shares and 25 per cent agreed months as they did last year, while 53 per cent said property might provide a means of boosting their they would like to save more, despite not currently cash pot. Peer to peer lending, Premium Bonds having enough disposable income to do so. and even investing in material goods such as classic cars and fine art were also mentioned. In contrast, only one in five said they would prefer to live for today rather than save for Helen added: “Diversifying their investments tomorrow and just 25 per cent were prepared can help some people get more out of their money, to take greater risks with their money to albeit with careful consideration for any risks involved. -

Virgin Trains Gives the Thumbs up to Stephen's Story

Jane receives her nameplate from the Virgin Trains team at Birmingham International Aug 20, 2019 09:00 BST Virgin Trains gives the thumbs up to Stephen’s Story • Stephen Sutton train nameplate presented to mum Jane • Virgin Trains auction off Pendolino nameplates for Teenage Cancer Trust • Sale expected to raise in excess of £15,000 and help Jane move closer to her £6m target Almost four years after naming a Virgin Trains Pendolino in her son Stephen’s honour, Jane Sutton returned to Birmingham International to be presented with one of the original nameplates. Stephen’s train - which is now sporting new vinyl nameplates, as part of a recent repaint programme - has been seen the length and breadth of the UK, clocking up over one million miles since its naming in September 2015. Jane was presented with the original nameplate by Amanda Hines, General Manager for Virgin Trains in the West Midlands. The second nameplate, along with ten others from the Virgin Trains fleet, will be auctioned off, with proceeds going to Stephen’s chosen charity, Teenage Cancer Trust. The eagerly sought after items of railway memorabilia are expected to raise around £15,000 contributing towards Jane’s £6m fundraising target. “We’re incredibly honoured to have had one of our Pendolinos carry Stephen’s name,” Amanda commented. “We needed to find a good home for the original nameplate so who better to present it to than his Mum Jane, who continues to work so tirelessly raising funds for teenage cancer” “The sale is a rare chance for someone to get their hands on a piece of railway history, so we are hopeful of raising a lot of money for Teenage Cancer Trust.” “It’s been a huge honour for one of Virgin Trains Pendolinos to carry Stephen’s name,” added Jane. -

To the House of Commons Parliamentary Debates

VOLUME 582 SIXTH SERIES INDEX TO THE HOUSE OF COMMONS PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) SESSION 2014–15 4th June, 2014—19th June, 2014 £00·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. INDEX TO THE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT SIXTH SERIES VOLUME 582 SESSION 2014–15 4th June, 2014—19th June, 2014 SCOPE The index is derived from the headings that appear in Hansard. The index includes entries covering the names of all Members contributing to the Parliamentary business recorded in Hansard, including Divisions. REFERENCES • References in the indexes are to columns rather than pages. • There are separate sequences in Hansard for the material taken on the floor of the House, Westminster Hall sittings, written statements, written questions, ministerial corrections and petitions • References consisting of a number by itself indicate material taken on the floor of the House. • References ending in ‘wh’ indicate Westminster Hall sittings. • References ending in ‘ws’ indicate written statements. • References ending in ‘w’ indicate written questions. • References ending in ‘p’ indicate written petitions. • References ending in ‘mc’ indicate ministerial corrections. • References under all headings except the names of Members contributing to Parliamentary business and the titles of legislation are listed in one numerical sequence irrespective of whether the material is taken on the floor -

Grant Recipients

Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme: Grant Recipients Below is a list of all projects for Phase 2 of the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme as of 15 July 2021. 49 public sector organisations have been awarded grants for 54 energy efficiency and heat decarbonisation projects. This is a list of all projects, therefore any organisations with multiple projects will be listed more than once. See the list of project summaries. SUMMARY North East £7,295,767 Yorkshire and the Humber £3,332,816 North West £4,658,108 East Midlands £5,197,723 West Midlands £15,868,939 East of England £7,603,562 South East £10,607,040 South West £9,949,044 Greater London £10,131,086 TOTAL £74,644,085 PUBLIC SECTOR DECARBONISATION SCHEME - GRANT RECIPIENTS Grant recipient Grant value Sector NORTH EAST County Durham and Darlington NHS £596,966 NHS Foundation Trust Gateshead NHS Foundation Trust £1,527,865 NHS Newcastle-upon-Tyne City Council £2,988,977 Local Authority Northumbria University £1,783,921 Further / Higher Education Institution University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne £284,443 Further / Higher Education Institution Woodland Primary School, County Durham £113,595 School / Academy NORTH EAST TOTAL: £7,295,767 YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER Barnsley College, South Yorkshire £141,720 Further / Higher Education Institution Enquire Learning Trust, Wakefield £237,946 School / Academy Humber Teaching NHS Foundation Trust £1,733,218 NHS Luminate Education Group, Leeds £1,219,932 Further / Higher Education Institution YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER TOTAL: £3,332,816 NORTH WEST Cheshire -

Youth Voice: Positive Stories

Youth Voice: Positive Stories May 2015 Youth Select Committee Youth Voice: Positive Stories A report by youth representatives and the workers that support them May 2015 Welcome to the May 2015 edition of Positive Stories. Our format reflects part of our commitment to the UN Convention on the Rights of a Child Article 13 - Freedom of expression ‘Every child must be free to say what they think and to seek and receive all kinds of information, as long as it is within the law,’ (UNICEF UK). The British Youth Council will share this report regionally and nationally, with local councillors and MPs, and certain media outlets, in order to raise the profile of the fantastic local work that we know is happening every day. The case studies and stories of the work of young people in their local communities are reproduced here in their own words. If you would like to find out more about one of the projects you read about in this report, please email: [email protected] The online survey remains open and we produce reports once a month, providing young people the opportunity to shout about the great work they have been doing in their local areas during the previous month. Previous reports are available online: http://www.byc.org.uk/uk- work/youth-voice The British Youth Council would like to thank all the workers and young people who took the time to promote and complete October survey and we look forward to hearing more from everyone over the coming months. 2 Contents Young People’s Stories East Midlands 4 East of England 7 London 9 North East 15 North West 16 South East 18 South West 30 West Midlands 46 Yorkshire and Humber 48 Northern Ireland 53 Support Worker Stories London 58 North East 59 North West 61 Yorkshire and Humber 62 3 Young People’s Stories East Midlands Derbyshire Asha Lawson-Haynes, 12, Member of Youth Parliament Derbyshire have put together a short YouTube manifesto, so far we only have the first copy but we are working on improving it and making it again. -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044854 on 7 April 2021. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on October 1, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044854 on 7 April 2021. Downloaded from Processes of care and survival associated with treatment in specialist teenage and young adult cancer centres: results from the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort study ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID bmjopen-2020-044854 Article Type: Original research Date Submitted by the 16-Sep-2020 Author: Complete List