Political Lawyers: the Structure of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert L. Tsai

ROBERT L. TSAI Professor of Law American University The Washington College of Law 4300 Nebraska Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20016 202.274.4370 [email protected] roberttsai.com EDUCATION J.D. Yale Law School, 1997 The Yale Law Journal, Editor, Volume 106 Yale Law and Policy Review, Editor, Volume 12 Honorable Mention for Oral Argument, Harlan Fiske Stone Prize Finals, 1996 Morris Tyler Moot Court of Appeals, Board of Directors Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic B.A. University of California, Los Angeles, History & Political Science, magna cum laude, 1993 Phi Beta Kappa Highest Departmental Honors (conferred by thesis committee) Carey McWilliams Award for Best Honors Thesis: Building the City on the Hilltop: A Socio-Political Study of Early Christianity ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Temple University, Beasley School of Law Clifford Scott Green Chair and Visiting Professor of Constitutional Law, Fall 2019 Courses: Fourteenth Amendment History and Practice, Presidential Leadership Over Individual Rights American University, The Washington College of Law Professor of Law, May 2009—Present Associate Professor of Law (with tenure), June 2008—May 2009 Courses: Constitutional Law, Criminal Procedure, Jurisprudence, Presidential Leadership and Individual Rights, The First Amendment University of Georgia Law School Visiting Professor, Semester in Washington Program, Spring & Fall 2012 Course: The American Presidency and Individual Rights University of Oregon School of Law Associate Professor of Law (with tenure), 2007-08 Assistant Professor, 2002-07 2008 Lorry I. Lokey University Award for Faculty Excellence (via nomination & peer review) 2007 Orlando John Hollis Faculty Teaching Award Courses: Constitutional Law, Federal Courts, Free Speech, Equality, Religious Freedom, Civil Rights Litigation Yale University, Department of History Teaching Fellow, 1996, 1997 CLERKSHIPS The Honorable Hugh H. -

The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court

The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court April 17, 2017 By Jeffrey Toobin they once did. We have the tools now to do all the research. With the Federalist Society, Leonard Leo has reared a We know everything they’ve written. We know what they’ve generation of originalist élites. The selection of Neil Gorsuch is said. There are no surprises.” Gorsuch had committed no real just his latest achievement. gaffes, caused no blowups, and barely made any news— which was just how Leo had hoped the hearings would unfold. Leo has for many years been the executive vice-president of the Federalist Society, a nationwide organization of conservative lawyers, based in Washington. Leo served, in effect, as Trump’s subcontractor on the selection of Gorsuch, who was confirmed by a vote of 54–45, last week, after Republicans changed the Senate rules to forbid the use of filibusters. Leo’s role in the nomination capped a period of extraordinary influence for him and for the Federalist Society. During the Administration of George W. Bush, Leo also played a crucial part in the nominations of John Roberts and Samuel Alito. Now that Gorsuch has been confirmed, Leo is responsible, to a considerable extent, for a third of the Supreme Court. Leo, who is fifty-one, has neither held government office nor taught in a law school. He has written little and has given few speeches. He is not, technically speaking, even a lobbyist. Leo is, rather, a convener and a networker, and he has met and cultivated almost every important Republican lawyer in more than a generation. -

Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts

SHAW.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2017 3:32 AM Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts Katherine Shaw* Abstract The President’s words play a unique role in American public life. No other figure speaks with the reach, range, or authority of the President. The President speaks to the entire population, about the full range of domestic and international issues we collectively confront, and on behalf of the country to the rest of the world. Speech is also a key tool of presidential governance: For at least a century, Presidents have used the bully pulpit to augment their existing constitutional and statutory authorities. But what sort of impact, if any, should presidential speech have in court, if that speech is plausibly related to the subject matter of a pending case? Curiously, neither judges nor scholars have grappled with that question in any sustained way, though citations to presidential speech appear with some frequency in judicial opinions. Some of the time, these citations are no more than passing references. Other times, presidential statements play a significant role in judicial assessments of the meaning, lawfulness, or constitutionality of either legislation or executive action. This Article is the first systematic examination of presidential speech in the courts. Drawing on a number of cases in both the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, I first identify the primary modes of judicial reliance on presidential speech. I next ask what light the law of evidence, principles of deference, and internal executive branch dynamics can shed on judicial treatment of presidential speech. -

Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum to Claims Court - Law360

9/24/2020 Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum To Claims Court - Law360 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum To Claims Court By Julia Arciga Law360 (September 22, 2020, 2:46 PM EDT) -- A Maryland-based former Kirkland & Ellis LLP associate will become a judge of the Court of Federal Claims for a 15-year term, after the U.S. Senate on Tuesday confirmed him by a 66-27 vote. Edward H. Meyers is a partner at Stein Mitchell Beato & Missner LLP, litigating bid protests, breach of contract disputes and copyright infringement. While at the firm, he served as counsel for one of the collection agencies in a 2018 consolidated protest action challenging the U.S. Department of Education's solicitation for student loan debt collection services. He clerked with Federal Claims Judge Loren A. Smith between 2005 and 2006 before spending six years as a Kirkland associate, where he worked as a civil litigator handling securities, government contracts, construction, insurance and statutory claims. He earned his bachelor's degree from Vanderbilt University and his law degree summa cum laude from Catholic University of America's Columbus School of Law — where he joined the Federalist Society and still remains a member. Judiciary committee members Sens. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., had raised questions about Meyers' Federalist Society affiliation before Tuesday's vote, and he confirmed that he did speak to fellow members throughout his nomination process. -

Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same-Sex Marriage Struggle

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications Winter 2012 The Terms of the Debate: Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same-Sex Marriage Struggle Mary Ziegler Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Mary Ziegler, The Terms of the Debate: Litigation, Argumentative Strategies, and Coalitions in the Same- Sex Marriage Struggle, 39 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 467 (2012), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/332 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TERMS OF THE DEBATE: LITIGATION, ARGUMENTATIVE STRATEGIES, AND COALITIONS IN THE SAME-SEX MARRIAGE STRUGGLE MARY ZIEGLER ABSTRACT Why, in the face of ongoing criticism, do advocates of same-sex marriage continue to pursue litigation? Recently, Perry v. Schwarzenegger, a challenge to California’s ban on same-sex marriage, and Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, a lawsuit challenging section three of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, have created divisive debate. Leading scholarship and commentary on the litigation of decisions like Perry and Gill have been strongly critical, predicting that it will produce a backlash that will undermine the same- sex marriage cause. These studies all rely on a particular historical account of past same-sex marriage decisions and their effect on political debate. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28, 2017 Thank you, Chris, for that kind introduction and for your tremendous work on behalf of our Second Amendment. Thank you very much. I want to also thank Wayne LaPierre for his unflinching leadership in the fight for freedom. Wayne, thank you very much. Great. I'd also like to congratulate Karen Handel on her incredible fight in Georgia Six. The election takes place on June 20. And by the way, on primaries, let's not have 11 Republicans running for the same position, okay? [Laughter] It's too nerve-shattering. She's totally for the NRA, and she's totally for the Second Amendment. So get out and vote. She's running against someone who's going to raise your taxes to the sky, destroy your health care, and he's for open borders—lots of crime—and he's not even able to vote in the district that he's running in. Other than that, I think he's doing a fantastic job, right? [Laughter] So get out and vote for Karen. Also, my friend—he's become a friend—because there's nobody that does it like Lee Greenwood. Wow. [Laughter] Lee's anthem is the perfect description of the renewed spirit sweeping across our country. And it really is, indeed, sweeping across our country. So, Lee, I know I speak for everyone in this arena when I say, we are all very proud indeed to be an American. -

The Tea Party Movement As a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 Albert Choi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/343 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 i Copyright © 2014 by Albert Choi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. THE City University of New York iii Abstract The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi Advisor: Professor Frances Piven The Tea Party movement has been a keyword in American politics since its inception in 2009. -

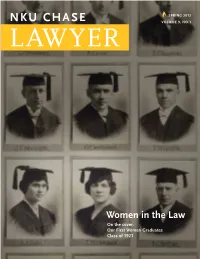

NKU CHASE Volume 9, No.1

Spring 2012 nKu CHASe volume 9, no.1 Women in the law on the cover: our First Women graduates Class of 1921 From the Dean n this issue of NKU Chase Lawyer, we celebrate the success of our women graduates. The law school graduated its first women in 1921. Since then, women have continued to be part of the Interim Editor IChase law community and have achieved success in a David H. MacKnight wide range of fields. At the same time, it is important to Associate Dean for Advancement recognize that there is much work to be done. Design If we are to be true to our school’s namesake, Chief Paul Neff Design Justice Salmon P. Chase, Chase College of Law should be a leader in promoting gender diversity. As Professor Photography Richard L. Aynes, a constitutional scholar, pointed out Wendy Lane in his 1999 article1, Chief Justice Chase was an early Advancement Coordinator supporter of the right of women to practice law. In 1873, then Chief Justice Chase cast John Petric the sole dissenting vote in Bradwell v. Illinois, a case in which the Court in a 8-1 decision Image After Photography LLC upheld the Illinois Supreme Court’s refusal to admit Myra Bradwell to the bar on the Bob Scheadler grounds that she was a married woman. The Court’s refusal to grant Mrs. Bradwell the Daylight Photo relief she sought is all the more notable because three of the justices who voted to deny her relief had previously dissented vigorously in The Slaughter-House Cases, a decision in Timothy D. -

The Most Popular President? - the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Va

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Features Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies 2-15-2005 The oM st Popular President? Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features Recommended Citation "The osM t Popular President?" (2005). Features. Paper 115. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Features by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Most Popular President? - The Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Va... Page 1 of 5 The Most Popular President? Abraham Lincoln on Bookshelves and the Web This weekend we celebrated the birthday of Abraham Lincoln -- perhaps the most popular subject among scholars, students, and enthusiasts of the presidency. In bookstores Lincoln has no rival. Not even FDR can compare -- in the past two years 15 books have been published about Lincoln to FDR's 10, which is amazing since that span included the 60th anniversaries of D-Day and Roosevelt's historic 4th term, and anticipated the anniversary of his death in office. Lincoln is also quite popular on the web, with sites devoted to the new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, his birthplace, home, and papers. And he is popular in the press -- perhaps no deceased former president is more frequently incorporated into our daily news. Below, the Hauenstein Center has gathered recently written and forthcoming books about Lincoln, links to websites, and news and commentary written about Lincoln since the New Year. -

Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress

Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress Updated June 5, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44321 SUMMARY R44321 Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in June 5, 2019 the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Kristy N. Kamarck Congress Specialist in Military Manpower Under Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the authority to raise and support armies; provide and maintain a navy; and provide for organizing, disciplining, and regulating them. Congress has used this authority to establish criteria and standards for individuals to be recruited, to advance through promotion, and to be separated or retired from military service. Throughout the history of the armed services, Congress has established some of these criteria based on demographic characteristics such as race, sex, and sexual orientation. In the past few decades there have been rapid changes to certain laws and policies regarding diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity – in particular towards women serving in combat arms occupational specialties, and the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals. Some of these changes remain contentious and face continuing legal challenges. Military manpower requirements derive from the National Military Strategy and are determined by the military services based on the workload and competencies required to deliver essential capabilities. Filling these capability needs, from combat medics to drone operators, often requires a wide range of backgrounds, skills and knowledge. To meet their recruiting mission, the military services draw from a demographically diverse pool of U.S. youth. Some have argued that military policies and programs that support diversity, inclusion, and equal opportunity can enhance the services’ ability to attract, recruit and retain top talent. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Heretical Queers: Gay Participation in Anti-Gay Institutions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1wp0j20r Author Radojcic, Natasha Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Heretical Queers: Gay Participation in Anti-Gay Institutions A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Natasha Radojcic June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Katja Gunether, Chairperson Dr. Karen Pyke Dr. Ellen Reese Copyright by Natasha Radojcic 2015 The Dissertation of Natasha Radojcic is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Heretical Queers: Gay Participation in Anti-Gay Institutions by Natasha Radojcic Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Sociology University of California, Riverside, June 2015 Dr. Katja Guenther, Chairperson This dissertations examines gay participation in anti-gay institutions, notably the Roman Catholic Church and the Republican Party. Using a comparative ethnographic approach, I explore Dignity, a group for gay Roman Catholics, and the Log Cabin Republicans, a group for gay Republicans in order to understand how members cope with marginalization they encounter in both the Church/Republican Party and the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) Community. I demonstrate that participants in these groups are simultaneously members of dominant and subordinate populations that draw on their racial, gender, and class based privilege to deal with the marginalization they experience. Accordingly, this dissertation shows how systems of inequality are replicated within the LGBT Community and within the Roman Catholic Church and the Republican Party. -

The Prez Quiz Answers

PREZ TRIVIAL QUIZ AND ANSWERS Below is a Presidential Trivia Quiz and Answers. GRADING CRITERIA: 33 questions, 3 points each, and 1 free point. If the answer is a list which has L elements and you get x correct, you get x=L points. If any are wrong you get 0 points. You can take the quiz one of three ways. 1) Take it WITHOUT using the web and see how many you can get right. Take 3 hours. 2) Take it and use the web and try to do it fast. Stop when you want, but your score will be determined as follows: If R is the number of points and T 180R is the number of minutes then your score is T + 1: If you get all 33 right in 60 minutes then you get a 100. You could get more than 100 if you do it faster. 3) The answer key has more information and is interesting. Do not bother to take the quiz and just read the answer key when I post it. Much of this material is from the books Hail to the chiefs: Political mis- chief, Morals, and Malarky from George W to George W by Barbara Holland and Bland Ambition: From Adams to Quayle- the Cranks, Criminals, Tax Cheats, and Golfers who made it to Vice President by Steve Tally. I also use Wikipedia. There is a table at the end of this document that has lots of information about presidents. THE QUIZ BEGINS! 1. How many people have been president without having ever held prior elected office? Name each one and, if they had former experience in government, what it was.