Flagler College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Beach County Project / Control Cross Reference Listing 2/8/2017

Palm Beach County Project / Control Cross Reference Listing 2/8/2017 NAME PROJECT CONTROL PAGE BOOK 10 Acre Dillman Property (Master) 00859-000 2002-00058 1001 Hibiscus Lane 00012-190 0000-000000034 118 101 North Federal Highway 00006-007 0000-000000022 099 101 SE 7th Avenue 00012-214 0000-000000058 122 104 NE 2nd Avenue Plat 00012-140 0000-000000120 114 10th and 10th Center 00012-149 0000-000000039 116 1100 Commerce Park 00036-002 0000-000000060 098 1112 South Flagler Drive 00074-315 0000-000000128 118 112th/Northlake Office 05764-000 2006-00529 1150 Skees Road 05007-000 2003-00072 14070 Paradise Point Plat Waiver 03100-582 0000-00000 150 Oceanside 00012-204 0000-000000181 119 1747 South Military Trail 05034-001 1984-00075 1747 South Military Trail 05034-001 2003-00041 1747 South Military Trail 05034-001 2007-00407 1771 South Congress Avenue 00070-033 0000-000000135 121 1800 North Military Trail 00006-052 0000-000000094 108 1801 Clint Moore Road 00006-116 0000-000000027 116 181st Street South Plat 00303-009 1972-001180007 057 1850 Okeechobee Blvd 05000-270 1995-00091 1960 Okeechobee Blvd 05000-335 1996-00075 1st Road - Hines Plat Waiver 03100-597 2006-00405 200 East Plat 00006-008 0000-000000020 100 2003 Tequesta Associates, LLC 00060-006 0000-000000007 100 2085 Zip Code Lane 05400-000 1997-00037 2091 Indian Road Rezoning 05446-000 1997-00107 2101 Australian 00074-324 0000-000000159 120 2295 South Ocean Blvd Condo 00050-010 0000-00000 2540 Okeechobee Blvd 05000-221 1977-00193 2645 Medical Center 00012-201 0000-000000117 119 2911 Nokomis -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

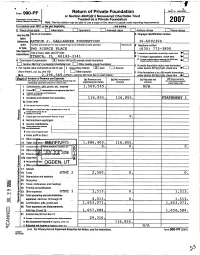

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation W

• 7 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation 0Mb 11. 1505-0052 or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal -anus -1ce l771 2007 Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2007 , or tax year beginning , and ending r Ph-L, +u th ,t a nnk , F--1 Init ,nl retu .n F-1 ein,I .nr „ rn F-1 e.nnnd.d rnfi,.n F-1 Ad.l r. a nhenl+n F--1 un...n ..1.ennn Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Use the IRS label. Otherwise , ARTHUR J. GALLAGHER FOUNDATION 36-6082304 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad Is not delivered to street address) RooMsulte B Telephone number ortype. TWO PIERCE PLACE ( 630 ) 773-3800 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C Instructions . If exemption application Is pending, check here ITASCA IL 60143-3141 0 1- Foreign organizations , check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ► H Check typea of organization X Section 501 ()()c 3 exempt private foundation check here and attach computation Section 4947 (a)( 1 ) nonexempt charitable trust = Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here .10.0 (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination $ 2 2 9 6 5 6 9 . -

The Reformed Church in 1910"

m4e 11:mhlntt of t4e ilefnrmeb C!tlfnrr!J in .Amrrt.-u W4t illrfnrtttth ilnw iutr4 ill4urr4 nf i;nrlrm ORGANIZED 1660 ~tatnrtral .&krtr}J BY THE REV. EDGAR TILTON, JR., D. D. MINISTER OF THE HARLEM CHURCH SINCE 1898 PUBLISHED BY THE CONSISTORY 1910 THE CONSISTORY. The Minister: REV. EDGAR TILTON, JR., D.D. The Elders: The Deacons: J" Al\IES D. S HIPl\iIAN GEORGE 1VARREN DUNN EDGA.R VANDERBILT WILLIAM G. GASTON EUGENE s. HAND WILLIAl\iI C. HANDS, }'I. D .. w ILLIAM T. DEl\iIAREST A. D. RocK,vELL, J"R. DAYID HENRY HENRY C. MENKEL Treasurer: PETER s. GETTELL THE CHLTRCH .Hl.TlLDlNGS. LENOX AVENUE, ONE HUND·RED TWENTY-THIRD STREET THIRD A VENUE, ONE HUNDRE]) TWENTY-FIRST STREE1T 5 MINISTERS OF THE HARLEM CHURCH: MARTINUS SCHOONMAKER . 1765-1785 JOHN FRELINGHUYSEN JACKSON 1791-1805 J EREl\1I.AH RO:}IEYN 1806-1813 CORNELIUS C. VERMEULE . 1816-1836 RICHARD LuDLo,v ScHOONl\iIAKER 1838-1847 JEREMIAH SKIDMORE LORD 1848-1869 GILES HENRY lVIANDEVILLE 1869-1881 GEORGE IIuTCHINSON SMYTH . 1881-1891 JOACHIM ELMENDORF 1886-1908 WILLIAM JUSTIN HARSHA 1892-1899 EDGAR TILTON., JR. .. 1898- BEN.JAMIN E. DICKHAUT . 1903-1909 Officers in the Harlem Church who served as Elders or Deacons before the War of the Revolution. JOHANNES BENSON JOHN NAGEL SAMSON BENSON JoosT VAN 0BLIENUS JOHN BOGERT PETER VAN 0BLIENUS DANIEL VAN BREVOORT JAN PIETERSON SLOT J. HENDRICKS VAN BRF.VOORT DANIEL T OURN"EUR JOHN KIERSEN JACQUES To URN EUR CoRNELIS JANSEN KoRTRIGHT JOHANNES VERMILYE GLAUDE LE ~1AISTRE JOHANNES VERVEELEN ADOLPH MEYER RESOLVED WALDRON ADOLPH 1'-IEYER, 3RD WILLIAM ,v ALDRON JAN LA l\tioNTAGNE, JR. -

Palm Beach County Control Number / Resolution Cross Reference Listing

Palm Beach County Control Number / Resolution Cross Reference Listing Control Name Control # Resolution 10 Acre Dillman Property 2002-00058A R-2003-1759 112th/Northlake Office 2006-00529 R-2008-1693 2006-00529 ZR-2007-61 1150 Skees Road 2003-00072 R-2004-2276 1650 N. Military Building 1980-00228 R-1981-48 1980-00228 R-2010-2 1980-00228 R-2011-1120 1980-00228 R-2011-1121 1980-00228 R-2011-1122 1980-00228 ZR-2009-43 1980-00228 ZR-2011-16 1690 Holding Corp 1974-00146 R-1974-768-E 1747 South Military Trail 2007-00407 R-2008-1356 2007-00407 R-2012-468 2007-00407 ZR-2008-49 1st Baptist Church of Loxatchee 1974-00058 R-1974-340 1st Federal Savings & Loan 1974-00114 R-1974-715 2091 Indian Road Rezoning 1997-00107 R-1998-414 2101 Indian Road Rezoning 1997-00106 R-1998-413 2141 Indian Road 1987-00063 R-1989-752 1987-00063A R-1998-415 Thursday, February 09, 2017 Page 1 of 367 Palm Beach County Control Number / Resolution Cross Reference Listing Control Name Control # Resolution 2440 Okeechobee Boulevard 1987-00025 R-1987-1102 1987-00025 R-2010-306 2500 Okeechobee Blvd 1978-00175 R-1978-1125 1978-00175A R-1983-1092 288 Tall Pines Road 2009-00566 R-2010-303 4 Points Market 1997-00102 R-1998-1125 1997-00102 R-1998-1126 1997-00102 R-1998-1304 1997-00102 R-2005-1125 1997-00102A R-1999-1149 4531 Mob-MUPD 1996-00113 R-1997-252 1996-00113 R-2012-277 1996-00113A R-1999-328 1996-00113A R-1999-522 45th Street Industrial Park 1977-00169 R-1977-1413 45th Street Office PCD 1983-00140 R-1984-172 1983-00140 R-1984-173 1983-00140A R-1987-200 5850 Okeechobee Blvd -

2012 Directory African American Presbyterian Congregations

2011 – 2012 Directory African American Presbyterian Congregations Louisville, KY ABOUT THE AFRICAN AMERIAN CONGREGATIONAL SUPPORT OFFICE The African American Congregational Support Office assists the Presbyterian Church (USA) in addressing the needs of African American Presbyterian Congregations. The office provides leadership at all levels of the denomination in order to strengthen the nurture and witness of African American Congregations. The main focus of the office is growth, health and vitality for these congregations and their ministries. This ministry works in partnership with presbyteries and congregations to help experience the unconditional love of God through Jesus Christ that empowers African American Presbyteries to be prophetic witnesses to the power of love to transform people, history, cultures and institutions. The African American Presbyterian legacy of prophetic leadership for justice and a culturally plural society has transformed the church and the world. The Black Presbyterian Church provides a forum for African American to share one another’s joys, concerns, achievements, sorrows and blessings. The Rev. John Gloucester began organizing the first African American congregation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1807. The founding leaders named the congregation First African Presbyterian Church. John Gloucester commenced his missionary efforts by preaching in private houses June 1807 with twenty-two persons – nine men and thirteen women were organized in the church. Our office encourages congregations to become empowered -

FORT WASHINGTON PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 21 Wadsworth Avenue, (Aka 21-27 Wadsworth Avenue, 617-619 West 174Th Street, Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission May 12, 2009, Designation List 414 LP-2337 FORT WASHINGTON PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 21 Wadsworth Avenue, (aka 21-27 Wadsworth Avenue, 617-619 West 174th Street, Manhattan. Built 1913-14; Thomas Hastings of Carrère & Hastings, architect, C.T. Wills, Inc. builders. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 2143, Lot 38 in part, excluding the Sunday School. On March 24, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Fort Washington Presbyterian Church and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of the law. A total of eight witnesses, including the church’s pastor, Reverend Carmen Rosario, and members of the congregation, and representatives of the Municipal Art Society, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, who testified about the building’s condition, and the Historic Districts Council, spoke in favor of the designation. There were no speakers in opposition to the designation. The Commission has received a letter of support from the Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America Summary Fort Washington Presbyterian Church, built 1913-14 to the designs of Thomas Hastings of the firm of Carrère & Hastings as a daughter church to West Park Presbyterian Church, is an imposing neo-Georgian building, notable for its broad simple massing and carefully-modulated refined detailing. Thomas Hastings was the surviving partner in one of the leading architectural firms in the United States, which had a nationally important reputation for its church designs. Hastings had a personal affiliation with project, since he was the son of the distinguished clergyman, the Rev. -

AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL of TRADE MARKS 19 October 2017

Vol: 31, No. 41 19 October 2017 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it on our website (www.ipaustralia.gov.au) by using the "Journals" link on the home page. The Australian Official Journal of Trademarks is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 19 October 2017 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes. 20064 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed. 20065 Applications for Extension of Time . 20063 Applications for Amendment . 20063 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection . 19723 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1877138 to 1879009. 19695 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed. 20066 Withdrawn. 20066 Refused. 20066 Cancellations of Entries in Register . 20068 Corrigenda . 20070 Notices . 20063 Opposition Proceedings . 20061 Removal/Cessation of Protection for Non-use Proceedings . 20069 Renewal of Registration/IR . 20068 Trade Marks Registered/Protected . 20061 Trade Marks Removed from the Register/IRs Expired . 20069 This Page Left Intentionally Blank For Information on the following please see our website: www.ipaustralia.gov.au or contact our Customer Service Network on 1300651010 Editorial enquiries Contact information Freedom of Information ACT Professional Standards Board Sales Requests for Information under Section 194 (c) Country Codes Trade Mark and Designs Hearing Sessions INID (Internationally agreed Numbers for the Indentification of Data) ‘INID’ NUMBERS in use on Australian Trade Mark Documents ‘INID’ is an acronym for Internationally agreed Numbers for the Identification of Data’ (200) Data Concerning the Application. -

West Park Presbyterian Church 165 West 86Th Street, Borough of Manhattan

WEST PARK PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 165 WEST 86TH STREET, BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN The West Park Presbyterian Church is considered to be one of the best examples of a Romanesque Revival style religious structure in New York City. The extraordinarily deep color of the red sandstone cladding is combined with the bold forms of the round-arched openings and soaring tower anchoring the corner of West 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. The West Park Presbyterian Church was founded in 1852 as the 84th Street Presbyterian Church and formerly occupied a wood chapel on 84th Street and West End Avenue. The church purchased the site of the present church at Tenth Avenue and West 86th Street in 1882 and commissioned Leopold Eidlitz to design a small brick chapel on the eastern end of the site on 86th Street in 1883. It was completed in 1885. Eidlitz was a prominent New York architect who designed many New York City buildings, such as sections of the Tweed Courthouse and St. George’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan. The Upper West Side’s population dramatically increased during the 1880s and the church quickly outgrew the chapel. In 1889 the church commissioned Henry Kilburn to greatly expand Eidlitz’s chapel and create the main church in a manner which joins the two buildings seamlessly. Kilburn, who also designed many private residences in New York, including a number in the Upper West Side/Central Park West Historic District, re-clad Eidlitz’s original brick chapel in sandstone during the construction of the new church, which was finished in 1890. -

SOUTH AFRICAN PROVINCE GROUP NAME MEETING ADDRESS MEETING DETAILS (C & CL = Closed/O = Open) CONTACT DETAILS AA Area

CONTACT DETAILS SOUTH AFRICAN MEETING DETAILS (C & GROUP NAME MEETING ADDRESS AA Area Office PROVINCE CL = Closed/O = Open) St Joseph's Church Hall, 28 Aspeling Sat 15:00 (O) Damian 063 336 2020 Street, Bloemendal, Port Elizabeth PE EASTERN CAPE BLOEMENDAL 041 452 7328 Holy Spirit Church Hall , Cnr Rensburg & Thu 19:30 (C) Elroy 082 498 0550 Harrington Street , Arcadia , PE PE EASTERN CAPE COMFORT 041 452 7328 Christ the King Anglican Church Hall , Fri 19:30 (CL) & Fri Patrick 084 789 Sable Road , Gelvandale, PE 19:30 Last (O) 6494 /Pieter W 072 267 6641 PE EASTERN CAPE GELVANDALE 041 452 7328 Assembly Café, 60 Caledon Street, Graaff Mon 18:00 (O) Anja 082 857 8728 Reinett SUNLAND SRV GRAAFF PE EASTERN CAPE REINETT 041 452 7328 Princess Alice Hall , 18 African Street , Mon 19:30 (O) Nolene 083 288 2537 Grahamstown PE EASTERN CAPE GRAHAMSTOWN PROTEA 041 452 7328 St Francis Anglican Church, Corner Thu 18:30 (O) Michael 079 826 6845 / Goedehoop & St Francis Streets, Jeffreys Charlene 082 064 3711 JEFFREYS BAY WAVES OF Bay PE EASTERN CAPE CHANGE 041 452 7328 68 PJ Retief Street , Joubertina Tue 19:00 (O) Mias 083 378 2195 PE EASTERN CAPE JOUBERTINA 041 452 7328 St Marks Anglican Church Hall , Cnr Mon 19:00 (O) Charles 083 411 8126 Voortrekker Road & Main Street (R102) , Humansdorp PE EASTERN CAPE LAMPLIGHT 041 452 7328 Lorraine Methodist Church Hall , Wed 19:30 (CL) Marilyn 074 586 Luneville Road , Lorraine, PE 3644 /Sandy 041 367 3411 PE EASTERN CAPE LORRAINE LADIES 041 452 7328 Malabar Primary School , Gladiola Mon 19:30 (O) Siva 072 834 -

Rochester Sentinel 2020 Wednesday January 1, 2020 Holiday-No Paper

Rochester Sentinel 2020 Wednesday January 1, 2020 Holiday-No Paper Thursday January 2, 2020 Rebecca Sue SLENTZ Rebecca Sue SLENTZ, 66, loving wife, mother, and grandmother, was called home by the Lord God on Sunday December 29, 2019, after a courageous fight for almost four years with cancer. Becky was born in Fulton County to the late Covert WENTZEL and Romayne (SMITH) WENTZEL. She was a 1971 graduate of Kewanna High School and a 1975 graduate of Manchester College, where she met her husband and partner of 45 years, Michael SLENTZ. Besides her husband, Michael, Becky is survived by three children, John (Angie) SLENTZ, Butler, Matt (Fei) SLENTZ, Austin, Texas, and Rachel (Matt) JUN, Mishawaka; four grandchildren, Rowan, Pearl, Robby and a granddaughter on the way; five siblings, Roger (Julie) WENTZEL, Falls Church, Virginia, Tim (Jeri) WENTZEL, Hicksville, Ohio, Don (Amy) WENTZEL, Fishers, Christy (Spencer) STOPA, Mesa, Arizona, and Carol HOLMQUEST, Fishers; and in-law Robert (Ann) SLENTZ, Butler. She truly enjoyed spending time with her beloved family, many close friends and her church family. An elementary school teacher for 40 years, the first two years at Orland Elementary and the last 38 years at Butler Elementary, teaching fifth grade, Becky loved helping and connecting with her students and she excelled at teaching math and coaching the math bowl team. Becky was an active member in the community, devoting her time to co-directing the Butler Community Food Pantry for 10 years, being a former member of the DeKalb County Young Farmers, leading the Franklin Busy Bees 4-H Club and being a 4-H mother for 17 years. -

Alumni Notes Alumni Notes Alumni Notes Policy » Send Alumni Updates and Photographs Directly to Class Correspondents

Alumni Notes Alumni Notes Alumni Notes Policy » Send alumni updates and photographs directly to Class Correspondents. » Digital photographs should be high- resolution jpg images (300 dpi). » Each class column is limited to 650 words so that we can accommodate eight decades of classes in the Bulletin! » Bulletin staff reserve the right to edit, format and select all materials for publication. Class of 1937 James Case 3757 Round Top Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822 [email protected] | 808.949.8272 The Class of 1937 graduated approximately 100 students. Only three of us are still alive. Betsy Knudsen Toulon lives on Kaua‘i with her Tim Yee ’44 and wife Janet hosted a class reunion luncheon at Waialae Country Club. Seated from left: Janet, husband, Al Toulon, who was a real estate a friend of the Yees, Tim and Aileen Kwock Char ’44. broker on Kaua‘i for many years. Betsy grew up on Kaua‘i and graduated from Lihue Grammar School before she entered Punahou Boeing his entire professional life. He was Class of 1938 as a boarding student. She went to college in known throughout the Northwest for his work Please email [email protected] if you’d like New York state and lived in various places on in restoring the ancient salmon breeding to serve as the Class Correspondent for the the mainland before she returned to Hawai‘i. spots in the high mountains. “Red Fish Lake,” at an altitude of about 6,500 feet, got its name Class of ’38. Deryk Row lives in Seattle, Washington, in a from the Native Americans because it was red Sadly, Bill Paty passed away in August.