The Development of Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the British Invasion of Egypt (1882) Through the Lens of Victorian Party Politics

Tarih Dergisi, Sayı 69 (2019/1), İstanbul 2019, s. 113-134 AN ANALYSIS OF THE BRITISH INVASION OF EGYPT (1882) THROUGH THE LENS OF VICTORIAN PARTY POLITICS Begüm Yıldızeli Dr. Öğr. Üyesi, Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi, İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi, Uluslararası İlişkiler Bölümü, Bilecik, Türkiye Abstract The British occupation of Egypt in 1882 meant a breakaway from the Anglo-French entente’s control over Ottoman financial system and the end of the Liberal Government’s ‘reluctant’ imperialism. When the Liberal ministry began in 1880, the cabinet immediately focused on foreign policies towards the Ottoman Empire subsequent to Gladstone’s campaign during the Bulgarian Agitation which had already turned out to be a party question. The protection of the Suez Canal as well as the interests of the British bondholders and the prestige of the British Empire was vital, which united the Liberal ministry and the Conservatives under the same purpose. Despite late Ottoman approval, the occupation signified the edge of Anglo-Ottoman alliance during the nineteenth century. This study will analyse why the Egyptian question is important for British party politics and to what extend the Anglo-Ottoman relations was affected with these circumstances. Keywords: Suez Canal, British Party Politics, Egypt, Urabi Pasha Öz VİKTORYA DÖNEMİ PARTİ SİYASETİ PERSPEKTİFİNDEN İNGİLİZLER’İN MISIR’I İŞGALİ (1882) ÜZERİNE BİR ANALİZ 1882 yılında İngilizler ’in Mısır’ı işgali gerek İngiliz Hükümeti’nin ‘gönülsüz’ emperyaliz- minin gerekse de Osmanlı ekonomisindeki -

Chapter 31 Notes: Societies at Crossroads

Chapter 31 Notes: Societies at Crossroads Chapter Outline I. Introduction: Ottoman empire, Russia, China, and Japan A. Common problems 1. Military weakness, vulnerability to foreign threats 2. Internal weakness due to economic problems, financial difficulties, and corruption B. Reform efforts 1. Attempts at political and educational reform and at industrialization 2. Turned to western models C. Different results of reforms 1. Ottoman empire, Russia, and China unsuccessful; societies on the verge of collapse 2. Reform in Japan was more thorough; Japan emerged as an industrial power II. The Ottoman empire in decline A. The nature of decline 1. Military decline since the late seventeenth century a. Ottoman forces behind European armies in strategy, tactics, weaponry, training b. Janissary corps politically corrupt, undisciplined c. Provincial governors gained power, private armies 2. Extensive territorial losses in nineteenth century a. Lost Caucasus and central Asia to Russia; western frontiers to Austria; Balkan provinces to Greece and Serbia b. Egypt gained autonomy after Napoleon's failed campaign in 1798 (a) Egyptian general Muhammad Ali built a powerful, modern army (b) Ali's army threatened Ottomans, made Egypt an autonomous province 3. Economic difficulties began in seventeenth century a. Less trade through empire as Europeans shifted to the Atlantic Ocean basin b. Exported raw materials, imported European manufactured goods c. Heavily depended on foreign loans, half of the revenues paid to loan interest d. Foreigners began to administer the debts of the Ottoman state by 1882 4. The "capitulations": European domination of Ottoman economy a. Extraterritoriality: Europeans exempt from Ottoman law within the empire b. -

2020 LOUTH GAA Club Championships Round 2 (Hurling)

2020 LOUTH GAA Club Championships Round 2 (Hurling) Round 3 (Football) Thursday 27th - Monday 31st August Round 2 Results Thursday 20th August 2020-Senior Hurling Championship St Fechins 1-05 Knockbridge 0-11 Friday 21st August 2020-Junior Championship Annaghminnon Rovers 1-10 Sean McDermotts 2-0 Naomh Malachi 0-13 Stabannon Parnells 0-07 LannLéire 3-06 Glyde Rangers 1-05 Saturday 22nd August 2020-Intermediate Championship Cooley Kickhams 0-09 Hunterstown Rovers 1-10 Roche Emmets 0-07 St Brides 2-15 Kilkerley Emmets 0-21 Clan na Gael 16 Sean O’Mahonys 0-13 Fechins 0-11 Sunday 23rd August 2020-Junior Championship Naomh Fionnbarra 0-13 Wolfe Tones 0-10 Sunday 23rd August 2020-Senior Championship St Josephs 2-09 Dundalk Gaels 2-06 Ardee St.Marys 1-12 Newtown Blues -0-14 O'Raghallaighs 2-11 Geraldines 2-11 Naomh Mairtin 2-15 Dreadnots 0-07 Monday 24th August 2020-Junior Championship John Mitchels 3-11 Na Piarsaigh 2-11 St Nicholas 1-06 Westerns 3-10 This Weeks Fixtures Thursday 27th August 2020 Senior Hurling Championship Naomh Moninne v Knockbridge at 7:30pm Friday 28th August 2020 Junior Football Championship Lannleire V Dowdallshill, 7pm Naomh Malachi v Wolfe Tones, 9pm Naomh Fionnbarra v Stabannan Parnells ,9pm Saturday 29th August 2020 Intermediate Football Championship Roche Emmets v St.Kevins, 2pm Sean O'Mahonys v Glen Emmets, 4pm Cooley Kickhams v Dundalk Young Ireland, 6pm Kilkerley Emmets v Oliver Plunketts, 8pm Sunday 30th August 2020 Junior Football Championship Cuchulainn Gaels v Annaghminnon Rovers, 11am Senior Football Championship -

The United States and the Crimean War, 1853-1856

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1972 The nitU ed States and the Crimean War, 1853-1856. William F. Liebler University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Liebler, William F., "The nitU ed States and the Crimean War, 1853-1856." (1972). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1319. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1319 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNITED STATES and the CRIMEAN WAR 1853 - 1856 A Dissertation Presented By William F. Liebler Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in for the degree of partial fulfillment of the requirements DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ^972 September ^ ^^onth) {year) Major Subject History 11 (C) William Frederick Liebler 1972 All Rights Reserved 111• • • THE UNITED STATES and the CRIMEAN WAR 1853 - 1856 A Dissertation By William F. Liebler Approved as to style and content by; Sep tejTiber 1972 n[mbnth) ~ TJear) CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I 1 CHAPTER II 28 CHAPTER III CHAPTER IV 77 CHAPTER V 101 CHAPTER VI 126 CHAPTER VII 153 CHAPTER VIII 165 CHAPTER IX 202 CHAPTER X 251 CHAPTER XI 258 CONCLUSION 291 NOTES 504 BIBLIOGRAPHY 519 CHAPTER I The first link in the chain of events leading up to the Crimean War was a dispute between Catholic and Ortho- dox monks over the custody of the Holy Places of the Chris- tian religion in Jerusalem. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

The Autonomy of Åland: a Reflexion of International and Constitutional Law

THE AUTONOMY OF ÅLAND: A REFLEXION OF INTERNATIONAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW By Christer Janson, Chief Legislative Officer, Åland Provincial Government 1. The historical background of the autonomy of lland ' . _ , Aland has had af Swedish population at least since the sixth century A.D. For this reason Aland, when the Kingdom of Sweden was formed, from the very beginning was a part of that country. The population of the Finnish mainland however was probably already at that time of Finnish origin. Only after the Swedish conquest of Finland during the thirteenth century Swedes started to settle in the coastal regions of .Finland. When the Swedish domination in Finland had been consolidated and Finland been made a part of the Kingdom of Sweden Aland was in some administrative, judicial and ecclesiastical respect made a part of the Abo (Turku) region. The reasons for this were purely practical and had no constitutional significance since Finland was an integrated part of the Kingdom of Sweden. In the seventeenth century Sweden was a superpower in the Baltic region. During the eighteenth century its significance diminished. Eventually Finland and Aland were lost to Russia through the peace treaty of Fredrikshamn (Hamina) in 1809. During the Crimean War 1853-56 the Russian fortress Bomarsund in Aland was destroyed by English and French fleets. At the peace negotiations Sweden who had stayed neutral during the war claimed Aland back to Sweden. However, Russia refused to give up Aland. On the other hand Russia was forced to commit itself not to build any fortifications in Aland (the so-called Aland Islands Servitude). -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 2 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... i Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... ii Biographical Register ........................................................................................................ 1 A .................................................................................................................................... 1 B .................................................................................................................................... 2 C .................................................................................................................................. 18 D .................................................................................................................................. 29 E ................................................................................................................................... 42 F ................................................................................................................................... 43 G ................................................................................................................................. -

Copyright by Yuri Andrew Campbell 2014

Copyright by Yuri Andrew Campbell 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Yuri Andrew Campbell Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Brothers Johnson: The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Black Business, and the Negro Image During the Progressive Era Committee: _________________________________ Juliet E. K. Walker, Supervisor _________________________________ Toyin Falola _________________________________ Leonard Moore _________________________________ Karl Miller _________________________________ Johnny S. Butler The Brothers Johnson: The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Black Business, and the Negro Image During the Progressive Era by Yuri Andrew Campbell, B.A., J.D. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University oF Texas at Austin In Partial FulFillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University oF Texas at Austin May 2014 Abstract The Brothers Johnson: The Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Black Business, and the Negro Image During the Progressive Era Yuri Andrew Campbell, PhD. The University oF Texas at Austin, 2014 Supervisor: Juliet E. K. Walker This dissertation looks at the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, the first Filmmaking concern owned and operated by African Americans with the intention oF producing dramas depicting the race in a positive Fashion. By undertaking a micro-level inquiry oF the LMPC the study provides an unusually detailed assessment oF the strengths and weaknesses of a Progressive-Era black entrepreneurial endeavor whose national reach had macro-level economic and cultural eFFect within the African-American commercial realm. On the micro-level, the dissertation adheres to the Cole model oF entrepreneurial history by addressing the Family, social, and employment backgrounds oF the two brothers who owned and operated the Film venture, Noble and George Johnson. -

A Case Study of the Natal Witness

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THE NATAL WITNESS by MARYLAWHON Submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of Master in Environment and Development in the Centre for Environment and Development, School ofApplied Environmental Sciences University ofKwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg 2004 ABSTRACT The media has had a significant impact on spreading environmental awareness internationally. The issues covered in the media can be seen as both representative of and an influence upon the heterogeneous public. This paper describes the environmental reporting in the South African provincial newspaper, the Natal Witness, and considers the results to both represent and influence South African environmental ideology. Environmental reporting In South Africa has been criticised for its focus on 'green' environmental issues. This criticism is rooted in the traditionally elite nature of both the media and environmentalists. However, both the media and environmentalists have been noted to be undergoing transformation. This research tests the veracity of assertions that environmental reporting is elitist, and has found that the assertions accurately describe reporting in the Witness. 'Green' themes are most commonly found, and sources and actors tend to be white and men. However, a broad range of discourses were noted, showing that the paper gives voice to a range of ideologies. These results hopefully will make a positive contribution to the environmental field by initiating debate, further studies, and reflection on the part of environmentalists, journalists, and academics on the relationship between the media and the South African environment. The work described in this dissertation was carried in the Centre for Environment and Development, University ofKwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, from July 2004 to December 2004, under the supervision ofProfessor Robert Fincham. -

A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo W Introduction and Summary of Lessons

Witness Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by William Bigelo w Introduction and Summary of Lessons . 3 Day One: Apartheid Simulation . ?C Day 'bo: Film-Witness to Apartheid . 7 Day Three: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" . 9 Day Four: Role Play4 New Breed of Children" (completion) . 11 Day Five: South Africa Letter Writing. 13 Reference Materials . 14 Additional Reading Suggestions for Student. Reading Suggestions for lkachers Additional Film Suggestions Student Handout #1 Privileged Minority. .......................... 15 Student Handout #2 The Bantustans . 16 Student Handout #3 Human Rights Fact Sheet. 17 Student Handout #4 Learning Was Defiance . 19 Student Handout #5 South African Student . 21 Student Handout #6 Challenging "Gutter Education". 23 a1987 Copyright by William Bigelow Published by The Southern Africa Media Center California Newsreel, 630 Natoma Street, San Francisco, CA 94103, (415) 621-6196 This "Raching Guide" made possible by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Design, typesetting, and production by Allogmph, San Francisco Film, Witness to Apartheid (classroom version): 35 minutes, 1986 Produced and directed by Sharon Sopher Co-produced by Kevin Harris Classroom version of Witness to Apartheid made possible by the Aaron Diamond Foundation. Introduction The story Witness to Apartheid tells is stark: children in South Africa - the same age as students we teach - are today being beaten, detained, even tortured. As one recent human rights report summarizes, the South African government is waging a 'kar against children.'' The images of Witness to Apartheid are not seen on the evening news: a father shares his feelings about the cold-blooded murder of his son by a South African policeman; a young woman describes the hideous torture she experienced while in police custody; a young man mumbles that he doesn't want to go on living - his beatings by security forces have left him permanently disabled. -

THE GREAT POWERS and the EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Boston University THE GREAT POWERS and the EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN CAS IR 325 / HI 229 Fall Semester 2014 Tuesday and Thursday 11:00-12:30 Prof. Erik Goldstein Office Hours: Tues./ Thurs. 2-3 Office: 152 Bay State Road, 3rd Floor Wednesday 10-11 Telephone: 353-9280 tel. preferred to email COURSE SYLLABUS Course Description This course will look at the Eastern Mediterranean as a centre of Great Power confrontation, and consider such issues as the impact of the competition on wider international relations, the domestic impact on the region of this involvement, the role of seapower, the origins and conduct on wars in the region, and attempts at conflict resolution. Objectives To provide an understanding of the nature of Great Power rivalry, to gain insight into the underlying factors affecting international relations in the Eastern Mediterranean, and to consider how governments evolve and implement policy. Requirements Mid-term examination 30% (16 Oct. 2014) Comprehensive final examination. 70% (to be detemined by University Registrar) All class members are expected to maintain high standards of academic honesty and integrity. The College of Arts and Sciences’ pamphlet “Academic Conduct Code” provides the standards and procedures. Cases of suspected academic misconduct will be referred to the Dean’s Office. Students are reminded that attendance is required, and reasons for non-attendance should be notified to the instructor. Cell phones are to be turned off. Repeated disruption caused by phones ringing will result in a grade penalty to be determined by the instructor. Core Readings Donald Quataert. The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922 (2000) Peter Mansfield. -

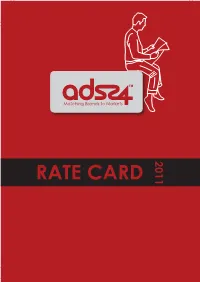

RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011

2011 RATE CARD ROP Rates Summary (MON-FRI) 1 Jan - 31 Dec 2011 Beeld (Mon, Tues) Beeld (Wed, Thurs, Fri) BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Beeld Main Body R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Beeld Main Body R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sake 24 R164.00 R192.00 R230.00 R230.00 Sport 24 R163.10 R228.60 R228.60 R228.60 Sport 24 R169.40 R237.40 R237.40 R237.40 BEELD BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC BEELD SUPPLEMENTS BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Jip R127.00 R172.50 R172.50 R172.50 Leefstyl R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Buite Beeld R146.10 R201.60 R201.60 R201.60 Motors R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 Vrydag R148.90 R205.50 R 205.50 R205.50 BEELD Oos Beeld R 46.10 R 64.80 R 64.80 R 64.80 Tshwane Beeld R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Mpumalanga Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Noordwes Beeld R 42.00 R 60.10 R 60.10 R 60.10 Wes Beeld R 40.90 R 54.60 R 54.60 R 54.60 Huisgids R 86.00 R113.60 R 113.60 R113.60 Die Burger (Mon, Tues) Die Burger (Wed, Thurs, Fri) DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC DIE BURGER Wes BW 1 Spot 2 Spot FC Burger Wes Main Body R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Main Body R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Promosies R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Promosies R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sake 24 R103.00 R119.00 R157.00 R157.00 Burger Wes Sport 24 R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Burger Wes Sport 24 R111.90 R130.00 R148.40 R171.70 Jip Wes R107.70 R125.10 R142.40 R165.30 Leefstyl