Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health Ethiopian Field Epidemiology Training Program (EFETP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

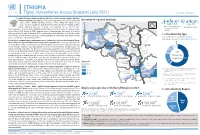

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

D.Fig 9.8-1 TRANSMISSION NETWORK STRUCTURE Area-01

D.Fig 9.8-1 TRANSMISSION NETWORK STRUCTURE 1 Area-01 (1/2, 2/2) 2 Area-02 3 Area-03 4 Area-04 5 Area-05 6 Area-06 (1/2, 2/2) 7 Area-07 Jimma 8 Area-07 Nekemte 9 Area-08 (1/2, 2/2) Legend; Link between A station and B station Frequency Band: Transmission Capacity; Expansion Capacity (At the 8th D.P. completion) in the Master Plan AB 7G 2M 7GHz 2M none AB ? 7x2M Not decided 7 x 2M none AB (2M) Not decided none 2M AB 7G 4x2M (+3) 7GHz 4 x 2M 3 x 2M Links among A, B C and D stations A BCD 5G STM-1 (+1) (+1) Frequency Band: Transmission Capacity; Expansion Capacity (At the 8th D.P. completion) in the Master Plan <Link between A and B> 5GHz STM-1 STM-1 <Link between B and C> 5GHz STM-1 none <Link between C and D> 5GHz STM-1 STM-1 1/11 D.Fig9.8-1 NW Structure.xls Sendafa Mt.Furi Mukaturi Chancho Entoto ? 2x2M (2M) ? 4x2M Addis Ababa Sheno South Ankober North Ambalay South Tik Giorgis Gara Guda 2G 8M 5G 3xSTM-1 5G STM-1 (+2) (+2) (+1) (+1) to Dessie to Bahir Dar Fetra Debre Tsige 900M 8M 11G 140M Sheno Town Ankober(Gorebela) (2M) 7G 4x2M (+1) Sululta 2G 2x34M OFC (2M) Gunde Meskel Muger ? 3x2M 2G 4x2M (2x2M) 900M 8M Aleltu Debre Sina Armania Lemi Robit (2M) 900M 2M (2M) (2M) Fitche Alidoro Chacha (+8) Mezezo Debre Tabor Rep Gunde Wein Abafelase (2M) (2M) (2M) 7G 4x2M Meragna Mendida Molale Inchini Kemet Gebrel Gohatsion Gebre Guracha 900M 8M (2x2M) (2M) (2M) ? 2x2M -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Partners' Guide to Ethiopia

PARTNERS’ GUIDE TO ETHIOPIA Africa Avenue, one of the main streets in Addis Ababa. One of the main streets in Addis Ababa. Welcome Statement from Dennis Weller Mission Director, USAID Ethiopia Mission Director Dennis Weller USAID/Ethiopia Dear Reader, If you’ve opened this guide, you have already As the home of the African Union and the United demonstrated an interest in development Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Addis opportunities in Ethiopia. That is an important Abeba is already the diplomatic hub of Africa. first step. Assuming Ethiopia continues on its current development track, it has the potential to become Boasting one of the highest GDP growth rates an economic hub. in the world over the past decade, Ethiopia is certainly on the rise. The Government of Ethiopia All of us at the United States Agency for was instrumental in leading that growth and International Development in Ethiopia (USAID) now has ambitious plans to move Africa’s second would like to encourage potential investors to most populous country and one of its poorest to look at the opportunities which Ethiopia offers middle-income status by 2025. In support of that and to consider investing if it makes sense. As a goal, it is investing heavily in its infrastructure and development agency, we like to say that our goal social services. is to one day work ourselves out of a job. That day may still be some way off in Ethiopia, but we’re For our part, USAID’s development portfolio optimistic that the growing involvement of the consists of a wide range of activities designed private sector in Ethiopia’s development will help to create opportunities for Ethiopian citizens. -

Amhara Claim of Western and Southern Parts of Tigray

AMHARA CLAIM OF WESTERN AND SOUTHERN PARTS OF TIGRAY By Mathza 11-26-20 We have been hearing and reading about the Amhara Regional State claim of ownership of the Welqayit, Tsegede, Qafta-Humera and Tselemti weredas (hereafter refereed to Welqayit Group) and Raya, and Amhara Regional State threats of war against TPLF/Tigray. One of the threats states “some of the Amhara elite politicians continue to beat drums, as summons to war” (watch/listen) DW TV (Amharic) - July 30, 2020. THE WELQAYIT GROUP Welkayit Amhara Identity Committee (WAIC) was formed in Gonder to return the Welqayit Group from Tigray Regional State to Amhara Regional State. The Welqayit Group was transferred to Tigray during the 1984 reconfiguration of the administrative structure of the country based on ethno-linguistical regional states (kililoch) after the Derg was defeated. It seems that the government of Eritrea has contributed to the Welqayit Group problem. According to ህግደፍንኣሸበርቲ ጉጅለታትን ብአንደበት…ቀዳማይ ክፋል (watch) the Eritrean government had trained Ethiopian oppositions and inculcated opposing views between ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly between Amhara and Tigray Regional States, wherever it viewed appropriate for its devilish objective of dismantling Ethiopia. The Committee recruited Tigrayans from Tigray Regional State to do its dirty work. An example is presented in a video, Tigrai Tv:መድረኽተሃድሶ ወረዳ ቃፍታ- ሑመራህዝቢ ጣብያ ዓዲ-ሕርዲ - YouTube (watch) aired on Feb 01, 2017. It shows confessions by a number of Tigrayans from Qafta-Humera who were lured and bribed by the Committee to serve its objectives. Each of them gave details of activities they participated in and carried out against their own people. -

Productive and Reproductive Performance of Local Cows Under Farmer’S Management in Central Tigray, Ethiopia

Nigerian J. Anim. Sci. 2020 Vol 22 (3): 70-74 (ISSN:1119-4308) © 2020 Animal Science Association of Nigeria (https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjas) available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Productive and reproductive performance of local cows under farmer’s management in central Tigray, Ethiopia Abrha B. H., Niraj K.*, Berihu G., Kiros A. and Gebregiorgis A. G. College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] (Mob: +251.966675736) Target audience: Ministry of Agriculture, Researchers, Dairy Policy Makers Abstract The study was conducted on 408 indigenous cows maintained under farmer’s management in eight districts of central Tigray, Ethiopia. A total of 208 small-scale dairy farm owners were randomly selected and interviewed with structured questionnaire to obtain information on the productive and reproductive performance of indigenous cows. The results of the study showed that the mean age at first calving (AFC) was 43.3 ±2.7 months, number of services per conception (NSC) was 2.7±0.5, days open (DO) was 201.47±61.21 days, calving interval (CI) was 468.33±71.42 days, lactation length (LL) was 206.17±32.33 days, lactation milk yield (LMY) was 414.65±53.69 litres for indigenous cows. The estimated value for productive and reproductive traits had higher than normal range in indigenous cows. This calls for a planned technical and institutional intervention for improved support services for appropriate breeding programs, improved cows and adequate veterinary health services. Key words: Productive and Reproductive Performance, Local Cows. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title One Law for Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5qn8t4jf Author Spielman, David Benjamin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies by David Benjamin Spielman 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia by David Benjamin Spielman Master of Arts in African Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ghislaine E. Lydon, Chair This thesis historically traces the development and interactions of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in Ethiopia. This analysis of the interactions between the Abrahamic faiths is primarily concerned with identifying notable periods of social cohesion in an effort to contest mainstream narratives that often pit the three against each other. This task is undertaken by incorporating a comparative analysis of the Ethiopian Christian code, the Fetha Nagast (Law of Kings), with Islamic and Judaic legal traditions. Identifying the common threads weaved throughout the Abrahamic legal traditions demonstrates how the historical development and periods of social cohesion in Ethiopia were facilitated. ii The thesis of David Benjamin Spielman is approved. Allen F. -

Democracy Under Threat in Ethiopia Hearing Committee

DEMOCRACY UNDER THREAT IN ETHIOPIA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 9, 2017 Serial No. 115–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–585PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:13 Apr 20, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\030917\24585 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. -

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire Always 001a. Your name: [NAME] Is this your name? ◯ Yes ◯ No 001b. Enter your name below. 001a = 0 Please record your name 002a = 0 Day: 002b. Record the correct date and time. Month: Year: ◯ TIGRAY ◯ AFAR ◯ AMHARA ◯ OROMIYA ◯ SOMALIE BENISHANGUL GUMZ 003a. Region ◯ ◯ S.N.N.P ◯ GAMBELA ◯ HARARI ◯ ADDIS ABABA ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${this_country} ◯ NORTH WEST TIGRAY ◯ CENTRAL TIGRAY ◯ EASTERN TIGRAY ◯ SOUTHERN TIGRAY ◯ WESTERN TIGRAY ◯ MEKELE TOWN SPECIAL ◯ ZONE 1 ◯ ZONE 2 ◯ ZONE 3 ZONE 5 003b. Zone ◯ ◯ NORTH GONDAR ◯ SOUTH GONDAR ◯ NORTH WELLO ◯ SOUTH WELLO ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST GOJAM ◯ WEST GOJAM ◯ WAG HIMRA ◯ AWI ◯ OROMIYA 1 ◯ BAHIR DAR SPECIAL ◯ WEST WELLEGA ◯ EAST WELLEGA ◯ ILU ABA BORA ◯ JIMMA ◯ WEST SHEWA ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST SHEWA ◯ ARSI ◯ WEST HARARGE ◯ EAST HARARGE ◯ BALE ◯ SOUTH WEST SHEWA ◯ GUJI ◯ ADAMA SPECIAL ◯ WEST ARSI ◯ KELEM WELLEGA ◯ HORO GUDRU WELLEGA ◯ Shinile ◯ Jijiga ◯ Liben ◯ METEKEL ◯ ASOSA ◯ PAWE SPECIAL ◯ GURAGE ◯ HADIYA ◯ KEMBATA TIBARO ◯ SIDAMA ◯ GEDEO ◯ WOLAYITA ◯ SOUTH OMO ◯ SHEKA ◯ KEFA ◯ GAMO GOFA ◯ BENCH MAJI ◯ AMARO SPECIAL ◯ DAWURO ◯ SILTIE ◯ ALABA SPECIAL ◯ HAWASSA CITY ADMINISTRATION ◯ AGNEWAK ◯ MEJENGER ◯ HARARI ◯ AKAKI KALITY ◯ NEFAS SILK-LAFTO ◯ KOLFE KERANIYO 2 ◯ GULELE ◯ LIDETA ◯ KIRKOS-SUB CITY ◯ ARADA ◯ ADDIS KETEMA ◯ YEKA ◯ BOLE ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${level1} ◯ TAHTAY ADIYABO ◯ MEDEBAY ZANA ◯ TSELEMTI ◯ SHIRE ENIDASILASE/TOWN/ ◯ AHIFEROM ◯ ADWA ◯ TAHTAY MAYCHEW ◯ NADER ADET ◯ DEGUA TEMBEN ◯ ABIYI ADI/TOWN/ ◯ ADWA/TOWN/ ◯ AXUM/TOWN/ ◯ SAESI TSADAMBA ◯ KLITE -

![Genotypes for Reaction to Tef Shoot Fly [Atherigona Hyalinipennis Van Emden], at Maysiye, Northern Ethiopia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3729/genotypes-for-reaction-to-tef-shoot-fly-atherigona-hyalinipennis-van-emden-at-maysiye-northern-ethiopia-923729.webp)

Genotypes for Reaction to Tef Shoot Fly [Atherigona Hyalinipennis Van Emden], at Maysiye, Northern Ethiopia

Vol. 10(6), pp. 146-152, June 2018 DOI: 10.5897/JPBCS2017.0711 Article Number: AB4F5B556961 ISSN 2006-9758 Copyright © 2018 Journal of Plant Breeding and Crop Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JPBCS Science Full Length Research Paper Genetic variation of tef [Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter] genotypes for reaction to tef shoot fly [Atherigona hyalinipennis Van Emden], at Maysiye, Northern Ethiopia Chekole Nigus Tigray Agricultural Research Institute, Axum Center, P. O. Box. 230, Axum, Ethiopia. Received 24 November, 2017; Accepted 29 January, 2018 One of the major biotic stresses that limits tef yield is insect pests attack. Of these tef, shoot fly is sporadically important insect pest in various tef growing areas of Ethiopia. Evaluation of diversity of tef germplasm in Ethiopia for the reaction tef shoot fly might give a chance to get host plant resistance. The main objective of this study was to assess the genetic variation among tef genotypes for their reaction to tef shoot fly. Field experiment was conducted in 2015 cropping season at Maysiye, Northern Ethiopia. The genotypes were planted in triple lattice design with three replications category of reaction of the tested tef genotypes for their reaction to shoot fly attack was adopted from the rating scale of the IRRI for rice. The study revealed that acc. 17 WJ was found to be the only genotype evaluated as resistant to tef shoot fly Atherigona hyalinipennis species. While the standard checks Quncho and Kora were grouped under the susceptible category, generally 10 tef genotypes were moderately resistance, 19 genotypes were moderately susceptible, 16 genotypes were susceptible, and three genotypes were highly susceptible to tef shoot fly attack. -

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1. Tigrey No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Adwa 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 2(*) Hawzen 12 3(*) Wukro 7 Per Feasibility Study 4(*) Samre 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Alamata 10 Total 55 1 Tahtay Adiyabo 8 2 Medebay Zana 10 3 Laelay Mayechew 10 4 Kola Temben 11 5 Abergele 7 Per Filed Survey by ETC 6 Ganta Afeshum 15 7 Atsbi Wenberta 9 8 Enderta 14 9(*) Hintalo Wajirat 16 10 Ofla 15 Total 115 1 Kafta Humer 5 2 Laelay Adiyabo 8 3 Tahtay Koraro 8 4 Asegede Tsimbela 10 5 Tselemti 7 6(**) Welkait 7 7(**) Tsegede 6 8 Mereb Lehe 10 9(*) Enticho 21 10(**) Werie Lehe 16 Per Filed Survey by ETC 11 Tahtay Maychew 8 12(*)(**) Naeder Adet 9 13 Degua temben 9 14 Gulomahda 11 15 Erob 10 16 Saesi Tsaedaemba 14 17 Alage 13 18 Endmehoni 9 19(**) Rayaazebo 12 20 Ahferom 15 Total 208 1/14 Tigrey D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 2. Affar No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Ayisaita 3 2 Dubti 5 Per Filed Survey by ETC 3 Chifra 2 Total 10 1(*) Mile 1 2(*) Elidar 1 3 Koneba 4 4 Berahle 4 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Amibara 5 6 Gewane 1 7 Ewa 1 8 Dewele 1 Total 18 1 Ere Bti 1 2 Abala 2 3 Megale 1 4 Dalul 4 5 Afdera 1 6 Awash Fentale 3 7 Dulecha 1 8 Bure Mudaytu 1 Per Filed Survey by ETC 9 Arboba Special Woreda 1 10 Aura 1 11 Teru 1 12 Yalo 1 13 Gulina 1 14 Telalak 1 15 Simurobi 1 Total 21 2/14 Affar D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 3. -

R4 Rural Resilience Initiative QUARTERLY REPORT | JANUARY - MARCH 2013 CONTENTS

R4 Rural Resilience Initiative QUARTERLY REPORT | JANUARY - MARCH 2013 CONTENTS Execu5ve summary 1 Status summary 3 Accomplishments this quarter 5 R4 Rural Resilience in Ethiopia: 2012 End of season assessment 7 R4 Rural Resilience in Senegal: Na5onal Policy Analysis 10 Conclusion 13 Appendix I: R4 partners and ins5tu5onal roles 14 Appendix II: Rural resilience event series 16 Appendix III: Media cita5ons and resources 17 Cover: At a community mee5ng in Michael Debir village in Ethiopia’s Amhara region, farmers look back to the 1980s as they recall which years had the most severe droughts. Through this exercise farmers are helping to design insurance contracts that will work best for them. Geoffrey McCarney / Interna)onal Research Ins)tute for Climate and Society (IRI) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For the 1.3 billion people living on less than a dollar a day who that the ini5a5ve integrates. Ini5ated in 2010, December, the depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, vulnerability to program builds on the ini5al success of HARITA (Horn of Africa climate-related shocks is a constant threat to food security and Risk Transfer for Adapta5on), an integrated risk management well-being. As climate change drives an increase in the frequency framework developed by Oxfam America, the Relief Society of and intensity of natural hazards, the challenges faced by food- Tigray (REST), together with Ethiopian farmers and several other insecure communi5es struggling to improve their lives and na5onal and global partners1 to enable poor farmers to livelihoods will also increase. The ques5on of how to build rural strengthen their food and income security through a combina5on resilience against climate-related risk is cri5cal for addressing of improved resource management (risk reduc5on), insurance global poverty.