The Lost Journalism of Ring Lardner Ring Lardner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

Read Book Who Was Babe Ruth?

WHO WAS BABE RUTH? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joan Holub,Ted Hammond,Nancy Harrison | 112 pages | 01 May 2012 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448455860 | English | New York, United States Who Was Babe Ruth? PDF Book Salsinger, H. New York: W. Louis Terriers of the Federal League in , leading his team in batting average. It was the first time he had appeared in a game other than as a pitcher or pinch-hitter and the first time he batted in any spot other than ninth. It would have surprised no one if, for whatever reason, Ruth was out of baseball in a year or two. Sources In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball- Reference. In addition to this stunning display of power, Ruth was fourth in batting average at. Smith, Ellen. The Schenectady Gazette. And somehow Ruth may have actually had a better year at the plate than he did in Although he played all positions at one time or another, he gained stardom as a pitcher. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. He was succeeded by Queen Elizabeth II in Over the course of his career, Babe Ruth went on to break baseball's most important slugging records, including most years leading a league in home runs, most total bases in a season, and highest slugging percentage for a season. Subscribe today. Ruth went 2-for-4, including a two-run home run. Ruth remained productive in For those seven seasons he averaged 49 home runs per season, batted in runs, and had a batting average of. -

National League News in Short Metre No Longer a Joke

RAP ran PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 11, 1913 CHARLES L. HERZOG Third Baseman of the New York National League Club SPORTING LIFE JANUARY n, 1913 Ibe Official Directory of National Agreement Leagues GIVING FOR READY KEFEBENCE ALL LEAGUES. CLUBS, AND MANAGERS, UNDER THE NATIONAL AGREEMENT, WITH CLASSIFICATION i WESTERN LEAGUE. PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE. UNION ASSOCIATION. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION (CLASS A.) (CLASS A A.) (CLASS D.) OF PROFESSIONAL BASE BALL . President ALLAN T. BAUM, Season ended September 8, 1912. CREATED BY THE NATIONAL President NORRIS O©NEILL, 370 Valencia St., San Francisco, Cal. (Salary limit, $1200.) AGREEMENT FOR THE GOVERN LEAGUES. Shields Ave. and 35th St., Chicago, 1913 season April 1-October 26. rj.REAT FALLS CLUB, G. F., Mont. MENT OR PROFESSIONAL BASE Ills. CLUB MEMBERS SAN FRANCIS ^-* Dan Tracy, President. President MICHAEL H. SEXTON, Season ended September 29, 1912. CO, Cal., Frank M. Ish, President; Geo. M. Reed, Manager. BALL. William Reidy, Manager. OAKLAND, ALT LAKE CLUB, S. L. City, Utah. Rock Island, Ills. (Salary limit, $3600.) Members: August Herrmann, of Frank W. Leavitt, President; Carl S D. G. Cooley, President. Secretary J. H. FARRELL, Box 214, "DENVER CLUB, Denver, Colo. Mitze, Manager. LOS ANGELES A. C. Weaver, Manager. Cincinnati; Ban B. Johnson, of Chi Auburn, N. Y. J-© James McGill, President. W. H. Berry, President; F. E. Dlllon, r>UTTE CLUB, Butte, Mont. cago; Thomas J. Lynch, of New York. Jack Hendricks, Manager.. Manager. PORTLAND, Ore., W. W. *-* Edward F. Murphy, President. T. JOSEPH CLUB, St. Joseph, Mo. McCredie, President; W. H. McCredie, Jesse Stovall, Manager. BOARD OF ARBITRATION: S John Holland, President. -

Ed 038 415 Te 001 801

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 038 415 TE 001 801 AUTHOR Schumann, Paul F. TITLE Suggested Independent Study Projects for High School Students in American Literature Classes. PUB DATE [69] NOTE 7p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$0.45 DESCRIPTORS American History, *American Literature, Analytical Criticism, *English Instruction, Group Activities, Independent Reading, *Independent Study, Individual Study, Literary Analysis, Literary Criticism, Literature, Research Projects, *Secondary Education, *Student Projects ABSTRACT Ninety-six study projects, for individuals or groups, dealing with works by American authors or America's history in the past 100 years are listed. (JM) 1111111010 Of NM, DOCATION &MAK MIKE Of INCA11011 01,4 nu woorM511011pummmum is mans4MMAIE MN 011611016 IT. POINTS Of VIEW01 OPINIONS SUM N NOT WSW EP112111OffICIAL ON* Of SIMON CC) LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF .LOS ANGELES pew N POLICY. O 0 SUGGESTED INDEPENDENT STUDY PROJECTS FOR HIGH SCHOOL LLB' STUDENTS IN AMERICAN LITERATURE CLASSES Dr. Paul F. Schumann Students are encouraged to substitute titles and topics of literary merit, with teacher prior approval, for any of those on the following list.Works by American authors or dealing with our nation in the past 100 years are to receive primary attention during this semester. However, reports incorporating comparisons with works by foreign authors are clearly acceptable. You may elect to work in small groups on certain of the projects if you secure teacher consent in advance. Certain of the reports may be arranged to give orally in your small group sessions. You will also be notified as to the due dates for written ones. It is vital that all reports be carefully substantiated with specific citation from the materials used. -

Sei “ !Opening of Inlet Terrace Club the Social Event Of

If someone advertises Cor a worker, 1J you ar>- 1..... ig to buy a home and there's a possibility that it’s a soon, don’t ancii'. that you must wait job for you, FIND OUT ABOUT IT, foJ a w h ile Io n ",-r— l>.it in v estig a te th e re al SOMEBODY is going to get it. esf ite ads and i.hen you’ll KNOW. (INCORPORATED W ITH W HICH IP* THE COAST ECHOI VOL. XXIII. W h o j t N o jz.i, V- • flRCULATJOX BOOKS OPEN TO ALL B E L M A R , N. J., F R ID A Y , S E P T E M B E R it, 1914 CIRCULATION BOOKS OPEN TO ALL Price Two Cents LABOR DAY SPORTS GOSSIP ^ ™ S E I “ !OPENING OF INLET TERRACE CLUB YACHT CLUB RACES Burlington, N. J. A GREAT SUCCESS Mr. Dunham of Newark, who h is been The Sunday school of the Methodist n ■ greatest crowds of the spending the summer at the ISuen;i Vista church will have their picnic at Clark’s THE SOCIAL EVENT OF THE SEASON sc,saw Jacoba again trim the Hotel, has returned to’his winter home. Landing tomorrow. They will meet at the church at 8.30 a. m. and go in Jackie in the afternoon yacht race on While attending the opening of t! Inlet strawrides and stages, Saturday, under the auspices of the WHITNEY WINS BIG 0 6 H .* m l Terrace Club, Mr. Dunham wa- one of Belmar Yacht club. -

Hallowed Place, Toxic Space: 'Celebrating' Steve Bartman And

. Volume 15, Issue 1 May 2018 Hallowed place, toxic space: ‘Celebrating’ Steve Bartman and Chicago Cubs’ Fan Pilgrimage Lincoln Geraghty, University of Portsmouth, UK Abstract: This paper is about travelling and exploring, assessing the historical importance of fan pilgrimages and the geographic spaces in which, and through which, fans travel to get closer to their object of fandom. But it also about how those spaces can become toxic, acting as painful reminders of the object turned bad, tragic failure and community rejection. Through a case study of the Steve Bartman incident during the 2003 National League baseball championship playoff game between the Chicago Cubs and Florida Marlins at Wrigley Field, and an auto-ethnographic study of the physical grounds and stadium, I present ongoing research into fan tourism and sports fandom. The vitriolic reception Bartman received when he inadvertently interfered with a potentially game-winning play that might have seen the Cubs reach their first World Series since 1945 highlights toxic fan behavior familiar to many sports. However, that the seat he occupied on the night serves as an unofficial monument to that moment suggests that even in great controversy and disappointment, Cubs fans find physical space and ‘being there’ just as important to winning or celebrating success. Fans of the Cubs are open in describing themselves as the unlucky losers (e.g. not having won the World Series since 1908 until only this past season), building a fan identity defined by a so- called ‘curse’ and based on years of past failures. Therefore, what happened around the Bartman incident and the fact that his seat is a fan tourist site visited by baseball fans and Cub enthusiasts alike tells us that being a fan is not just about celebrating the good or remembering the great but also about recognizing the bad and mourning the worst. -

Ruth Makes 43D Homer, but Yankees Lose to Indians.Dodgers Beaten In

Ruth Makes 43d Homer, but Yankees Lose to Indians.Dodgers Beaten in Thirteenth Caldivell Has a Elliott's Error Delightful Wonder What a Dog Left at Home Thinks About : : : : ßy briggs Afternoon at Polo Grounds Sends B'klyn Dor-i-T GET IT . WAV) G14 OF /M-l The shabby, , \ (3ö\m vuovju ( The MO&... \ TnfrsK Nine to Defeat Slim Holds Former Teammates in Cheek low OR^'RV TRICK'S, WiErvt \ vAJAUJr» Ray Despite POw/m/ A" TALL Wa\nE- LV(\UJF of it the madper LFA^^G r^e HERE ALL FIR.ST CAME HERE' \T MAV8E if ' Back lomó Efforts of Bodie to Turn Tide; Boh - Cheap Passed Ball Mighty Ping M-QMe? when Thgv WAvS ALL. HOKtY PI £ llfOÖUGH THE DOOR WILL I <3ET The by Robins9 Shawkey Allows Two Runs Before Settling Down KMOVoJ VeßV WELL. THAT A^P I Ö0T MORE FLV CREM OR some- ¿KATES* TUST VAJAIT Catcher Allows Reds to I Ju"ST IOVG MOTORING ATTENTION! IH/Nrsi A i «ah ï THirM.6 - br-b-RAWF Till <SET i,hg«v> Tie Score in the Eighth \V. O. McGeehan child- put novai WJAVaJp vajoöp-- HER.E1-- \'LL \<SrMOR\~ By They Treat me lik6 From a Special Correspondent lifted his home run over the roof at the Tolo THiHfVA 19. "Babe'feRuth forty-third A. A- a- vt>et_u a Doc CINCINNATI, Aug. Rowdy ds yesterday, and personally scored the two lone runs of the Yanks, Elliott cost the Brooklyn Dodgers but "Babe" Ruth, even when aided and abbetted to a considerable extent another game to-day when he let in a run a ball the Wonderful Wop, could not do it all. -

Congressional Record—Senate S906

S906 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE January 23, 2007 Flint and a regional manager in my Hummel was nominated for a Pul- ting-edge approach to community Flint/Saginaw/Bay office in the Senate, itzer Prize in 1980 and the National emergency response shines as a model Connie has been my link to the com- Sportswriters and Sportscasters Asso- for all communities in Kentucky and munity. She is a respected community ciation named him Missouri Sports- the United States. This is a true exam- leader in her own right. Through the writer of the Year on four separate oc- ple of Kentucky at its finest and a years, she has mentored interns and casions. Now as the 57th winner of the leadership example to the entire Com- staff members, many of whom have J.G. Taylor Spink Award, presented monwealth.∑ caught her zeal for public service and annually for ‘‘meritorious contribu- f have kept in touch with her long after tions to baseball writing,’’ Hummel they left the office. will be recognized in a permanent ex- TRIBUTE TO JANE BOLIN My staff and I will miss her sense of hibit at the National Baseball Hall of ∑ Mrs. CLINTON. Mr. President, today humor, boundless energy, optimism Fame. He joins such legendary sports- I honor the life and legacy of Ms. Jane and enthusiasm, although I am certain writers as Red Smith, Ring Lardner, Bolin. that retirement will not stop her from Grantland Rice, and Damon Runyon. Jane Matilda Bolin of Queens, NY, staying involved. I also know that I congratulate Rick Hummel on this passed away on Monday, January 8, many people in Michigan, whose lives achievement and recognize his accom- 2007 after a lifetime of public service. -

W. P. KINSELLA's SHOELESS JOE and PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON's FIELD of DREAMS AS ARCHETYPICAL BASEBALL LITERATURE by DEBRA S

W. p. KINSELLA'S SHOELESS JOE AND PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON'S FIELD OF DREAMS AS ARCHETYPICAL BASEBALL LITERATURE by DEBRA S. SERRINS, B.A. A THESIS IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved December, 1990 / ^^> /l/-^ /// ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee. Dr. Mike Schoenecke and Dr. John Samson, for their time and expertise throughout my writing process. I would especially like to thank Dr. Schoenecke for his guidance, assistance, and friendship throughout the last four years of my education. I would also like to thank the Sarah and Tena Goldstein Scholarship Foundation Fund for their financial assistance and my close friends and family for their continuous support. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii CHAPTER I. MAJOR MOVEMENTS AND WORKS IN BASEBALL LITERATURE 1 Movements and Themes in Baseball Literature 1 Two Types of Baseball Literature 2 Henry's Good Baseball Stories: The Frank Merriwell Tradition 3 Notable Ba.seball Literature 5 Noah Brooks's The Fairport Nine 9 Ring Lardner's Baseball Fiction 9 Bernard Malamud's The Natural 11 Mark Harris's Works 13 Phillip Roth's The Great American Novel 18 Robert Coover's The Universal Baseball Association. Inc.. J. Henrv Waugh. Prop. 19 II. THE RECEPTION AND CRITICISM OF SHOELESS JOE 22 Shoeless Joe's Origin 22 Major Criticisms of Shoeless Joe 22 Summary of Shoeless Joe 24 The Theme of Love in Shoeless Joe 29 The Theme of Baseball in Shoeless Joe 34 The Theme of Religion in Shoeless Joe 39 The Theme of Dreams in Shoeless Joe 42 111 III. -

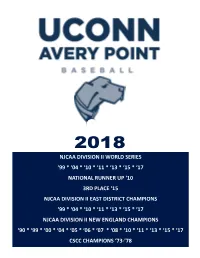

Njcaa Division Ii World Series '99 * '04 * '10 *

NJCAA DIVISION II WORLD SERIES ‘99 * ‘04 * ‘10 * ‘11 * ‘13 * ‘15 * ‘17 NATIONAL RUNNER UP ‘10 3RD PLACE ‘15 NJCAA DIVISION II EAST DISTRICT CHAMPIONS ‘99 * ‘04 * ‘10 * ‘11 * ‘13 * ‘15 * ‘17 NJCAA DIVISION II NEW ENGLAND CHAMPIONS ‘90 * ‘99 * ‘00 * ‘04 * ‘05 * ‘06 * ‘07 * ‘08 * ‘10 * ‘11 * ‘13 * ‘15 * ‘17 CSCC CHAMPIONS ‘73-’78 Letter from the Athletic Director The 2018 Baseball season is quickly approaching the 48th season UCONN AVERY POINT has fielded a Varsity Team, and I reflect on the history of the program as I approach my retirement on August 1st, 2018. The time has sped by to quickly as I clearly remember playing on the 1st Avery Point Championship Team in 1973, winning the Connecticut Small College Conference Championship under Coach George Greer. Defeating Stamford UCONN to clinch the championship with teammates like Pat Kelly, Jeff Kirsch, Herb Gardner, Jerry Stergio, Jay Macko and Mike Wilkinson to name a few. Playing a modest 10 game schedule that fall of 1973 started a streak of 15 consecutive CSCC Championships. When George Greer left to coach Davidson College in 1982, I left UCONN as their baseball graduate assistant to replace Coach Greer as the Athletic Director and Head Baseball Coach and ultimately joining the NJCAA in 1985. This has led to 14 NJCAA New England Championships, 7 East District Championships and 7 World Series appearances. There has been 37 Professional Baseball signee’s, 3 major Leaguers -John McDonald, Rajai Davis and Pete Walker-, 180 players playing at 4 year programs including 56 to UCONN and 18 NJCAA All-Americans. -

The Art Education of Recklessness: Thinking Scholarship Through the Essay

The Art Education of Recklessness: Thinking Scholarship through the Essay DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Mark Morrow, M.A. Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education and Policy The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: John Richardson, Ph.D., Advisor Jennifer Richardson, Ph.D. Sydney Walker, Ph.D. Copyrighted by Stephen Mark Morrow 2017 Abstract This document has been (for me, writing) and is (for you, reading) a journey. It started with a passing remark in Gilles Deleuze’s 1981 book Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. That remark concerned the cliché. The psychic clichés within us all. The greatest accomplishment of the mind is thinking, which according to Deleuze means clawing through and beyond the cliché. But how? I found in my research that higher education art schools (like the higher education English departments in which I had for years taught) claim to teach thinking, sometimes written as “critical thinking,” in addition to all the necessary skills of artmaking. For this dissertation, I set off on a journey to understand what thinking is, finding that Deleuze’s study of the dogmatic image of thought and its challenger, the new image of thought—a study he calls noo-ology—to be quite useful in understanding the history of the cliché and originality, and for understanding a problematic within the part of art education that purports to use Deleuzian concepts toward original thinking/artmaking. This document is both about original contributions to any field and is my original contribution to the field. -

AMH 4220 Spring 2009 1

AMH 4220 Spring 2009 1 AMH 4220: The United States in the Progressive Era, 1890-1920 Spring 2009 TR 12:30-1:45 208 HCB Instructor: Prof. Jennifer Koslow Office: Bellamy 409 Email: [email protected] Phone: 644-4086 (emails will be answered 9am-4pm Monday - Friday) Office Hours: Tuesday & Thursday Class website: http://campus.fsu.edu/ 2:00-3:00pm and by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION: Can you have an industrial democracy? This question preoccupied Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. This course looks at the development of the United States as an urban, industrial, and multicultural society from 1890 to 1920. In addition, we will study the attempts of the United States to rise as a world power. This course devotes special attention to the nation’s effort to accommodate old values with new realities. Please be aware that as an upper-division level history course, this class is reading and writing intensive. While this course has no prerequisites, if you have not had a survey course of American History (especially 1877 to the present) then I strongly recommend you secure a textbook and read the few chapters on the Progressive Era. COURSE OBJECTIVES: At the end of this course 1. The student will be able to recount pivotal events from turn-of-the-twentieth century America 2. The student will be able to describe in detail how urbanization, industrialization, and immigration shaped American society 3. The student will be able to write an expository essay 4. The student will be able to analyze a primary source 5.