On Reading Faiz by Aamer Hussein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 37/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Composite) Supplementary Examination, 2019 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite Supplementary Examination, 2019 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under: Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -4E -1E Appeared: 3515 Passed: 1411 Pass Percentage: 40.14 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance II IV V VII XI 16251 07-WR-441 GHZAL SAIIF Fail SAIF-U-LLAH R/A till A-22 III V VII 16252 09-IB.b-3182 Mudssarah Kousar Fail Muhammad Aslam R/A till S-22 II IV V VI VII 16253 2012-WR-293 Sonia Hamid Fail Abdul Hamid R/A till S-22 III V VI VII VIII IX 16254 2013-IWS-46 Ifra Shafqat Fail Shafqat Nawaz R/A till S-22 III VI VII VIII IX 16255 2012-IWS-238 Fahmeeda Tariq Fail Tariq Mahmood R/A till S-22 II VII VIII IX XII XIII 16256 2019-IUP(M-II)- Rehana Kouser Fail 00079 Dilber Ali R/A till S-22 IV V VI VII IX 16257 2012-WR-115 Faiza Masood Fail Masood Habib Adil R/A till S-22 III IV V VI VII 16258 02-WR-362 Nayyer Sultana Fail Rahmat Ali R/A till S-22 III IV VI VII VIII IX 16259 2015-WR-151 Rafia Parveen Fail Noor Muhammad -

Shia Target Killing Report

PAKISTAN 31/12/2012 Shaheed Detail in January 2012 Name Date City Reason Nisar Ahmed s/o Sardar Muhammad 18-Jan-12 Quetta Gun Shot Ghulam Muhammad s/o Ghulam Ali 16-Jan-12 Karachi Gun Shot Ghulam Raza 15-Jan-12 Karachi Gun Shot S. Mushtaq Zaidi 12-Jan-12 Karachi Gun Shot Kalb-e-Abbas Rizvi 9-Jan-12 Karachi Gun Shot Dr Jamal 7-Jan-12 Peshawar Gun Shot ASI Ghullam Abbas 5-Jan-12 Quetta Target killing Mushkoor Hussain 5-Jan-12 Lahore Target killing DSP Ibrahim 4-Jan-12 Gilgit Target killing Ghulam Abbas 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Faiz Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Abad Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Zahid Abbas 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Asad Abbas 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Mureed Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Akhter Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Mohammed Ashaq 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Khezhar Hayat 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Amjad Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Sadam Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Abad Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Aatif 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Adnan 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Faisal Hayat 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Tahir Abbas 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Syed Hussain 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Qurban Hussian 15-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Ghulam Qadir 17-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Shahnawaz 17-Jan-12 Khanpur Bome Blast Ali Hussain s/o Muzaffar Abbas 22-Jan-12 Karachi Target killing Asghar Karrar 19-Jan-12 Karachi Target killing Dr. -

Book Review Essay Siren Song

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 6 Article 41 August 2020 Book Review Essay Siren Song Taimur Rahman Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rahman, Taimur (2020). Book Review Essay Siren Song. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(6), 516-519. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss6/41 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Siren Song1 Reviewed by Taimur Rahman2 The title of this book is extremely misleading. This is not a book about siren songs. Or perhaps it is, but not in the way you think. The book draws you in, dressed as a biography of prominent Pakistani female singers. And then, you find yourself trapped into a complex discussion of post-colonial philosophy stretching across time (in terms of philosophy) and space (in terms of continents). Hence, any review of this book cannot be a simple retelling of its contents but begs the reader to engage in some seriously strenuous thinking. I begin my review, therefore, not with what is in, but with what is not in the book - the debate that shapes the book, and to which this book is a stimulating response. -

Koppal-Davanagere-Tumkur- Approved List Bidaai-201920

Bidaai-201920 Koppal-Davanagere-Tumkur- Approved List REG NAME OF THE Name of the Account SL.NO. TALUK Holder Amount NO BENEFICIARY Father/Mother 1 79/2018-19 Gangavthi KHAJABNI KHAJABANI 25000 2 92/208-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN SHAHAJADIBI 25000 3 128/18-19 KOPPAL ASMA BEGUM SHAHIDA BEGUM 25000 4 82/18-19 KOPPAL MABOOBI RAMJA BEE 25000 5 76/18-19 KOPPAL RIZVANA KHAM SALIMA BEGAM 25000 6 78/18-19 KOPPAL RESHMA MODINA BI 25000 7 88/18-19 KOPPAL BIBI ASHIYA BEGUM BIBI BEGUM K HABEEBA 25000 8 83/19-19 KOPPAL MARDAN BEE IMAMSAB 25000 9 99/18-19 KOPPAL AYISHA BANU NILOFAR 25000 10 107/18-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN BANU BI 25000 11 129/18-19 KOPPAL CHAND BI IMAM SAB 25000 12 122/18-19 KOPPAL TASLEEM BANU SHAKILA BANU 25000 13 85/18-19 KOPPAL RUKSANA PIRAMBI 25000 14 101/18-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN BANU JAIRABEE GUDDADAR 25000 15 115/18-19 KOPPAL SANIHA TABASUM SANIHA TABASSUM 25000 16 127/18-19 KOPPAL HEENA TAZ BABUSAB DAMBAL 25000 17 96/18-19 KOPPAL RUBIYA BEGUM SHAHAJAD BEGUM 25000 18 108/18-19 KOPPAL SABEEHA BANU KHAJABANI MAJEERA 25000 19 89/2018-19 KOPPAL RUKSHANA BEGUM Rukshana Begum 25000 20 120/2018-19 KOPPAL NISHAMA FATHIMA Raheema Begum 25000 21 136/2018-19 KOPPAL Ashabee KHAJA BEE 25000 MAMTAJBI BASHUSAB 22 80/2018-19 KOPPAL Sabina Begum 25000 VALIKAR 23 106/2018-19 KOPPAL Yasmeen Kasim Sab 25000 24 79/2018-19 KOPPAL Mohaseena Nafees Hafiza bi 25000 25 84/2018-19 KOPPAL Navina Begum Mabusab Yenni 25000 26 91/2018-19 KOPPAL Shamina Begum Fathimabi 25000 27 132/2018-19 KOPPAL Yasmeen Arifa Begum 25000 28 121/2018-19 KOPPAL Parveen Mamataj Begum 25000 29 134/2018-19 -

Newsletter July 2018 | Issue 25 | Half Yearly

NEWSLETTER JULY 2018 | ISSUE 25 | HALF YEARLY Celebrating 35 Years of Excellence in Mental Health Care CEO’s Message I am pleased to present the Newsletter of Karwan- free of cost treatment, has set an example for many to follow. e-Hayat with great happiness. This year, we are The last six months have been very busy, crowded as they were with celebrating Karwan’s 35 years of excellence in a number of events, workshops, fundraisers, awareness sessions, mental health care. Karwan-e-Hayat has been at the zakat campaign and most of all the 1st International Conference on forefront in redefining and introducing innovative Psychosocial & Psychiatric Rehabilitation, which was a huge success. practices through which mental healthcare is I am thankful to all the supporters, employees and friends of Karwan provided to the people of Pakistan. Our successful without whom this success would not have been possible. I wish you all model of being a network of paperless hospitals, providing happy reading and a prosperous year ahead and hope for your continued indiscriminate quality mental healthcare and above all providing 90% support. Thank you Zaheeruddin Babar Yadain Karwan’s Annual Fundraising Event This year Karwan’s annual Fundraiser was on 17th & 18th February 2018, at The Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, where renowned artist, Humaira Channa, performed on two magical musical evenings of songs and ghazal. She sang ghazals of legends like Madam Noor Jehan, Mehdi Hasan, Farida Khanum, Ahmed Rushdi and many more. The show was hosted by well-known music composer, artist and friend of Karwan, Mr. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

UBL Employee Pension Fund Trust

UBL Employee Pension Fund Trust Employees Retrenched in 1997 on Pension Fund Scheme List of complete retrenched employees in terms of Supreme Court Orders; Column1 EMPNO EMPLOYEE_NAME 1 113148 SYED ZAFAR ALI 2 113290 IQBAL PERVEZ MIRZA 3 113333 MIAN AHSAN HABIB 4 113388 MUHAMMAD LATIF KHAN 5 113397 S M PARWEZ AKHTAR 6 113449 MUHAMMAD QAYYUM MIRZA 7 113689 MUHAMMAD YUNUS 8 113865 SAADAT ALI 9 113883 SHAH BEHRAM QURESHI 10 113908 CH NAZIR AHMED 11 114361 MUHAMMAD AFZAL 12 114662 MOHAMMAD ASLAM 13 114811 JAMIL UR REHMAN 14 114884 MOHAMMAD ASHRAF JANJUA 15 114909 ANWAR HUSSAIN 16 114945 ZAMIR AHMED 17 114963 MUHAMMAD QUDDUS HASAN SIDDIQUI 18 115016 NASIM AHMED 19 115131 MUHAMMAD HANIF 20 115326 ABDUL QADIR AWAN 21 115423 MUHAMMAD ASHFAQUE 22 115654 ANSAR AHMED 23 115779 MUHAMMED SIDDIQUE ABA ALI 24 115788 WASIM AKHTAR GHANI 25 115867 ABOOBAKER 26 115919 MIRZA AFLAQ BEG 27 116211 SALEEM A BANA 28 116239 MUHAMMAD ISMAIL KHAN AFRIDI 29 116372 GHULAM HUSSAIN 30 116789 TURAB ALI A FRAMEWALA 31 116798 GHULAM AKBAR 32 116804 MUHAMMAD AMIN 33 116877 MUHAMMAD AMIN KHAN 34 117009 MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BAKKER 35 117188 MUHAMMAD IQBAL 36 117197 ALEXANDER MATHEWS 37 117452 KAMALUDDIN 38 117513 S SHAH NAWAZ ZIA 39 117586 ABDUL RAZZAQ TAI 40 117896 BADRUDDIN 41 117984 GUL ALAM KHAN Column1 EMPNO EMPLOYEE_NAME 42 118037 NASEER AHMED 43 118426 MANNAN AHMED 44 118648 S ANJUM HUSSAIN NAQVI 45 119010 MUHAMMAD YAQOOB 46 119199 ZAFAR IQBAL BHATTI 47 119223 RAIS AKHTAR 48 119375 QADRI MUHAMMAD SHAFI 49 119481 MUHAMMED IQBAL 50 119746 ABDUL QAYYUM 51 119807 IQBAL DAYALA -

Faizghar Newsletter

Issue: January Year: 2016 NEWSLETTER Content Faiz Ghar trip to Rana Luxury Resort .............................................. 3 Faiz International Festival ................................................................... 4 Children at FIF ............................................................................................. 11 Comments .................................................................................................... 13 Workshop on Thinking Skills ................................................................. 14 Capacity Building Training workshops at Faiz Ghar .................... 15 [Faiz Ghar Music Class tribute to Rasheed Attre .......................... 16 Faiz Ghar trip to [Rana Luxury Resort The Faiz Ghar yoga class visited the Rana Luxury Resort and Safari Park at Head Balloki on Sunday, 13th December, 2015. The trip started with live music on the tour bus by the Faiz Ghar music class. On reaching the venue, the group found a quiet spot and spread their yoga mats to attend a vigorous yoga session conducted by Yogi Sham- shad Haider. By the time the session ended, the cold had disappeared, and many had taken o their woollies. The time was ripe for a fruit eating session. The more sporty among the group started playing football and frisbee. By this time the musicians had got their act together. The live music and dance session that followed became livelier when a large group of school girls and their teachers joined in. After a lot of food for the soul, the group was ready to attack Gogay kay Chaney, home made koftas, organic salads, and the most delicious rabri kheer. The group then took a tour of the jungle and the safari park. They enjoyed the wonderful ambience of the bamboo jungle, and the ostriches, deers, parakeet, swans, and many other wild animals and birds. Some members also took rides on the train and colour- ful donkey carts. -

Alphabetical List of Successful

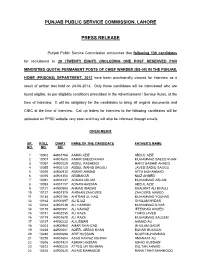

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE PRESS RELEASE Punjab Public Service Commission announces that following 139 candidates for recruitment to 28 (TWENTY EIGHT) (INCLUDING ONE POST RESERVED FOR MINORITIES QUOTA) PERMANENT POSTS OF CHIEF WARDER (BS-09) IN THE PUNJAB, HOME (PRISONS) DEPARTMENT, 2012 have been provisionally cleared for interview as a result of written test held on 24-06-2013. Only those candidates will be interviewed who are found eligible, as per eligibility conditions prescribed in the Advertisement / Service Rules, at the time of interview. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring all original documents and CNIC at the time of interview. Call up letters for interview to the following candidates will be uploaded on PPSC website very soon and they will also be informed through emails. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10002 44901764 AAMIR AZIZ ABDUL AZIZ 2 10007 44901600 AAMIR SAEED KHAN MUHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 3 10037 44900229 ABDUL RASHEED HAFIZ BASHIR AHMED 4 10055 44902129 ABDUL WAHID SAGGU JAVED SADIQ SAGGU 5 10070 44900932 ABRAR AHMAD ATTA MUHAMMAD 6 10075 44901304 ABUBAKAR NIAZ AHMED 7 10091 44901437 ADNAN ASLAM MUHAMMAD ASLAM 8 10093 44901157 ADNAN HASSAN ABDUL AZIZ 9 10121 44900993 AHMAD WAQAS SHAUKAT ALI BHALLI 10 10127 44901379 AHSAAN ZAHOORE ZAHOORE AHMED 11 10136 44902186 AHTRAM UL HAQ MUHAMMAD YOUNAS 12 10162 44900697 ALI EJAZ GHULAM HYDAR 13 10164 44901539 ALI HASSAN MUHAMMAD ILYAS 14 10170 44900551 ALI NAWAZ IFTEKHAR AHMED 15 10181 44902255 ALI RAZA TARIQ JAVED 16 10179 44901678 ALI RAZA MUHAMMAD SALEEM 17 10197 44900222 ALIUSMAN AHMAD ALI 18 10203 44900962 AMAR SHAHZAD GHULAM QADIR 19 10238 44900001 AQEEL ABBAS KHAN BAHAR HUSSAIN 20 10246 44900898 ARIF HUSSAIN NOOR MUHAMMAD 21 10270 44901604 ASAD NAWAZ ASHRAF AMANAAT ALI 22 10306 44901524 ASRAR HASSAN ASHIQ HUSSAIN 23 10312 44900220 ATTEQ UR REHMAN SULTAN AHMAD 24 10315 44900625 AWAIS MAHMOOD RANA TAHIR MAHMOOD 25 10334 44900474 BADAR MUNIR GHULAM YASIN 26 10349 44901771 BILAL HASAN M.HUSSAIN 27 10359 44900086 CH. -

Newsletter 2020

SHAIGAN 02 ISSUE | 2020 INTERCOM ISO 9001:2015 ISO/IEC 17025:2017 WWW.SHAIGAN.COM SHAIGAN Newsletter DAUGHTER DAY ZEDRON LAUNCH ISO CERTIFICATION HIGHLIGHTS Page 09 Page 01 Page 5 Femicare CME Highlights A Single topic conference Page 03 on “Pain Management Page 07” SINGLE TOPIC CONFERENCE Digital Campaign Punjab History & Culture Page 11 during Covid Page 16 Page 14 Pakistan Society of Hepatology Naran Kaghan CME (PSH) - 2020 Virtual Conference Page 15 Designed By: Malik M. Shaiq Page 13 Compiled by : Sheikh Saqib Edited by: Fasiha Qaiser Follow us on: Product Life Cycle New Joiners Promotions Page 21 Page 24 Page 25 [email protected] Issue 02 | 20 01 02 ISO CERTIFICATION It is to announce with immense pleasure that, under the Visionary Leadership of Shaigan higher management along with years of hard work, dedication and commitment to excellence, Shaigan Pharmaceuticals (Pvt.) Ltd achieved one more milestone by obtaining following ISO Certifications: 1. ISO 45001 : 2018 - Occupational Health & Safety 2. ISO 14001 : 2015 - Environment Management System 3. SCOPE OF SUPPLY - Good Distribution & Storage Practices Along with previously obtained ISO certifications i.e. ISO 9001: 2015- Quality Management System and ISO 17025: 2017- Lab Accreditation Shaigan has become the only Pharmaceutical manufacturing Industry with Multiple ISO Certifications and remarkable systems and quality operations. The Shaigan’s management is committed to provide its workforce the environment which will further nourish their personal and professional capabilities. On this happiest achievement let we all pray for prosperity and success of Shaigan. Shaigan Newsletter www.shaigan.com 05 05 06 06 DAUGHTER DAY HIGHLIGHTS 27th SEPTEMBER 2020 Femicare Business Unit has celebrated Daughter Day (International date 27th Septem- ber) in the month of September 2020 in which 16 wards of most potential public institutes were engaged at National level. -

At Quaid's Service

At Quaid’s Service: A Journey Towards Discovery Jinnah Rafi Foundation LAHORE At Quaid’s Service: A Journey Towards Discovery Syed Razi Wasti Jinnah Rafi Foundation LAHORE PUBLICATION NO.2 JINNAH RAFI FOUNDATION EMPIRE CENTRE, GULBERG II LAHORE. FIRST EDITION: 1996 PRINTED BY A.W.PRINTERS LAHORE Jinnah Rafi Foundation was set up in 1989, commemorating Rafi Butt - a young follow- er of Quaid - whose son is its Chairman. The foundation is committed to upholding the aspirations of Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah. All its resources are devoted to encouraging scholarly research on topics relating to Pakistan’s political, social and economic interests, which were so close to Rafi Butt’s heart. ISBN 969-8246-01-0 “Read no history: nothing but biography, For that is life without theo- ry.” - Benjamin Disraeli CONTENTS FOREWORD - AKBAR S. AHMAD 1 INTRODUCTION 5 1. MUSLIMS IN SOUTH ASIA _ PARTICULARLY IN THE PUNJAB TILL 1947 9 2. LAHORE IN 1930s AND 1940s - RAFI BUTT FROM MODEST BEGINNINGS TO BIG INDUSTRIALIST 22 3. QUAID-I-AZAM AND RAFI BUTT 65 4. RAFI BUTT - THE MAN HE WAS. 80 EPILOGUE 111 APPENDICES 1. Correspondence between Quaid-i-Azam and Rafi Butt. 120 2. Main Ihsan Ilahi’s letter dated 27 June 1938. 152 3. Report of the All India Muslim League Planning Committee. 154 4. Documents pertaining to Central Exchange Bank Ltd. 162 5. Advertisement by Saeed Sehgal. 174 6. Prospectus of the West Punjab Steel Corporation Ltd. 175 7. Report of Rafi Butt’s election to the Lahore Municipal Corporation. 175 8. Documents about Punjab Muslim Chamber of Commerce and ad- dress presented to Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Presented All India Muslim League.