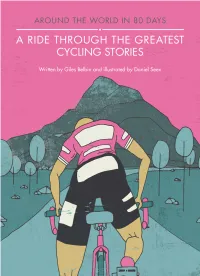

“The Great Moral Crusade of Cycle-Sport”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maurice GARIN

Vainqueur du 1 er Tour de France en 1903, son nom reste lié à l’histoire de la « plus grande épreuve cycliste jamais organisée » ainsi que l’annonce le journal L’Auto du 19 janvier 1903 Maurice GARIN Né le 3 mars 1871 à 17 heures à Arvier (Val d’Aoste) Italie Source : Grazia Bordoni via Didier Geslain Décédé le 19 février 1957 à 7 heures à Lens Pas-de-Calais 62 selon acte n°123 Sa victoire inaugure le 1er Tour de France et le fait entrer dans la légende de la grande boucle qui, en 2013, démarre sa 100e édition. Maurice Garin, l’ancien montagnard du Val d’Aoste, remporte cette première édition devant 60 compagnons de route. Il avale les 2428 km en 94 h 33’ 14 ‘’ à la vitesse moyenne de 25,67 km/h, en six étapes, du 1 er juillet au 19 juillet 1903. Le deuxième, Lucien Pothier met 2 h 49 de plus que lui. Ce premier Tour de France ne connaît pas les régles d’aujourd’hui : les coureurs se débrouillent pour s’alimenter et faire leurs réparations eux-mêmes, sans aucune aide, avec un matériel archaïque et un seul vélo autorisé. Toutefois, il est disputé seulement en plaine, ce qui convient bien aux qualités de rouleur de Garin. Celui-ci est aidé par sa phénoménale résistance qui lui permet de ne jamais manger sur le vélo, en dépit de la distance de chacune des étapes supérieures à 400 kilomètres. Le Café « Au réveil matin », le jour du départ de la première étape Son palmarès éloquent en fait le favori de ce 1 er Tour de France Quand le coup de feu retentit à 15h 16, ce 1 er juillet 1903 aux abords de l’auberge « Au Réveil matin » à Montgeron (Essonne), c’est le signal du départ pour les soixante coureurs cyclistes qui s’élancent pour la première étape d’une course qui deviendra mythique : le Tour de France. -

Le Journaliste Sportif Est-Il Un Journaliste Comme Les Autres ?

2018 Mémoire de fin d’études Mastère « Journalisme de sport » Le journaliste sportif est-il un journaliste comme les autres ? PRESENTE PAR SYLVAIN FALCOZ DIRECTEUR DE MEMOIRE : YASMINA TOUAIBIA Promotion Pierre Barbancey 1 Résumé L’étude qui va être menée dans les pages suivantes vise à questionner la place et la reconnaissance du journaliste sportif vis-à-vis de ses confrères des autres rubriques. L’analyse de la manière dont il travaille, le rapport qu’il entretient avec ses sources, permettront notamment de comprendre quelles sont ses spécificités, et de déterminer s’il est réellement un journaliste comme les autres. Chaque été, principalement les années où se déroulent des événements sportifs planétaires (Jeux Olympiques, Coupe du Monde de football…) le journaliste sportif est mis sur le devant de la scène. Et ce d’autant plus que la période estivale n’est pas toujours la plus faste en matière d’actualité journalistique. Mais bien souvent, la mise en lumière de ces conteurs du sport ne leur est pas forcément bénéfique. Raillé pour son chauvinisme exacerbé, sa proximité avec les athlètes ou ses envolées lyriques, le journaliste sportif n’a pas toujours bonne presse. Etroitement lié à son objet d’étude, à ses traditions, et à ce qu’on aurait coutume d’appeler « la grande famille du sport », ce dernier s’est construit à travers des singularités qui permettent de se demander s’il exerce en tous points le même métier que ces nombreux confrères. Summary The following study aims at questionning on the place and recognition of the sports journalist with respect to his colleagues working in the other sections. -

2021 Tri Boulder Official Athlete Guide

2021 TRI BOULDER OFFICIAL ATHLETE GUIDE Long Course Boulder Beast Triathlon & Aquabike Olympic & Sprint Triathlon, Duathlon & Relays Saturday, July 24th, 2021 Boulder Reservoir, 5565 N 51st St Boulder, CO 80301 We can't wait to get to racing at the Boulder Reservoir! Saturday is going to be a great day with temperatures reaching 88°F during the race. The water temperature at Boulder Reservoir as of July 13th is 77°F Packet Pick Up Dates, Times & Locations Thursday, July 22nd 4:00pm - 7:00m Boulder Cycle Sport - North 4580 North Broadway Suite B, Boulder, CO 80304 Friday, July 23rd 3:00pm - 7:00pm Road Runner Sports Westminster 10442 Town Center Dr Suite 300, Westminster, CO 80021 Saturday, July 24th ($10 race day pick up fee) 5:45am - 7:30am Finish Line Trailer Boulder Reservoir Parking Lot / Finish Line Please arrive at least 1 hour before your start time if you plan to pick up your packet on race morning. Race Day Parking - The park entry fee will be waived until 7:15am for everyone, however anyone who arrives after 7:15am should be prepared to pay the regular park entrance fee. Athletes and spectators will follow parking attendants in the morning to the Reservoir’s north or south overflow lots. Water Temp & Sunday’s Expected Weather Forecast – The air temperature on Sunday is expected to reach 88°F by midday. Boulder Reservoir's water temperature is 77°F (as of July 13th). Transition - Only participants will be allowed in transition. If you would like to see your family and friends, make sure they are on the other side of the barricades. -

T-2 Bicycle Retailer & Industry News • Top 100 Retailers 2007 Www

T-2 Bicycle Retailer & Industry News • Top 100 Retailers 2007 www.bicycleretailer.com The Top 100 Retailers for 2007 were selected because they excel in three ar- eas: market share, community outreach and store appearance. However, each store has its own unique formula for success. We asked each store owner to share what he or she believes sets them apart from their peers. Read on to learn their tricks of the trade. denotes repeat Top 100 retailer ACME Bicycle Company Art’s SLO Cyclery Bell’s Bicycles and Repairs Katy, TX San Luis Obispo, CA North Miami Beach, FL Number of locations: 1 Number of locations: 3 Number of locations: 1 Years in business: 12 Years in business: 25 Years in business: 11 Square footage: 15,500 Square footage (main location): 5,000 Square footage: 15,000 Number of employees at height of season: 20 Number of employees at height of season: 20 Number of employees at height of season: 12 Owners: Richard and Marcia Becker Owners: Scott Smith, Eric Benson Owner: James Bell Managers: same Manager: Lucien Gamache Manager: Edlun Gault What sets you apart: Continuous improvement—be it customer What sets you apart: Many things set us apart from our competitors. What sets you apart: We pride ourselves on our service, repairs and service, product knowledge, inventory control, or simply relationship One thing is that we realize customers can shop anywhere. Knowing fi ttings. Most of our guys are certifi ed for repairs. We have a separate building—there is always room to improve. There is always some- this, we create an experience for them above and beyond coming full-service repair shop. -

Download Cycle and Skate Sports Strategy

8/07/15 About this document Contents This document is the DRAFT Cycle Sport and Skate Strategy. A second Trends and Demand ................ 2 volume, the Supporting Document, Cycle sports ........................................ 2 provides more details concerning the Off-road, BMX and mountain biking 2 existing facilities and community Cycle clubs ....................................... 3 engagement findings. Skating and Scooters .......................... 3 Acknowledgements Facilities in Whittlesea ............. 4 City of Whittlesea would like to Cycle sports facilities .......................... 4 acknowledge the support and Skate and scooter facilities ................. 5 assistance provided by: Key Issues and Future • Victorian Government in Directions ................................ 7 partnering to develop the strategy A sustainable planning framework for future provision .................................. 7 Equitable distribution of central, social and easy to get to facilities....... 7 Facilities designed, constructed and managed so they are in line with best practise ............................................. 11 • Project Working Group (including Programs, events and competitions at James Lake, Patricia Hale, James suitable venues ................................. 12 Kempen, Lenice White and Fran One or more sustainable cycle clubs 12 Linardi) Goals ..................................... 13 • Council staff who contributed to the completion of this project Key Directions ....................... 13 • Organisations, retailers, -

Tour De France

Tour de France The Tour de France is the world’s most famous, and arguably the hardest, cycling race. It takes place every year and lasts for a total of three weeks, covering almost 3,500km. History of the Race During the late 19th century, cycling became a popular hobby for many people. As time went on, organised bike races were introduced and professional cycling became very popular in France. On 6th July 1903, 60 cyclists set off on a race and covered 2,428km in a circular route over six stages. 18 days after setting off, 21 of the original 60 cyclists made it back to the finish line in Paris. The winner was Maurice Garin and the Tour de France was born. Except for war time, the race has taken place every year since then and has become more challenging with the addition of mountain climbs and longer distances. The Modern Tour de France Each year, the tour begins in a different country. The route changes annually too, though usually finishes on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. In 2019, the race starts in Brussels, Belgium on the 6th July and ends in Paris on the 28th July after 21 stages totalling a distance of 3,460km. There are 22 teams taking part in the Tour de France, each with eight riders. The reigning champion is Welsh cyclist Geraint Thomas. Coloured Jerseys Yellow jersey Green jersey Red polka dot jersey White jersey (maillot jaune) (maillot vert) (maillot à pois rouges) (maillot blanc) Worn by the Worn by the King of the Mountains jersey Fastest overall race leader at rider with the – worn by the first rider to rider under the each stage. -

Vincitori, Team Di Appartenenza, Km Gara E Velocità Media

Vincitori, team di appartenenza, km gara e velocità media 2015 John Degenkolb (Ger) Giant-Alpecin 253.5 km (43.56 km/h) 2014 Niki Terpstra (Ned) Omega Pharma-Quick Step 259 km (42.11 km/h) 2013 Fabian Cancellara (Swi) RadioShack Leopard 254.5 km (44.19 km/h) 2012 Tom Boonen (Bel) Omega Pharma-Quickstep 257.5 km (43.48 km/h) 2011 Johan Vansummeren (Bel) Team Garmin-Cervelo 258 km (42.126 km/h) 2010 Fabian Cancellara (Swi) Team Saxo Bank 259 km (39.325 km/h) 2009 Tom Boonen (Bel) Quick Step 259.5 km (42.343 km/h) 2008 Tom Boonen (Bel) Quick Step 259.5 km (43.407 km/h) 2007 Stuart O'Grady (Aus) 259.5 km (42.181 km/h) 2006 Fabian Cancellara (Swi) 259 km (42.239 km/h) 2005 Tom Boonen (Bel) 259 km (39.88 km/h) 2004 Magnus Backstedt (Swe) 261 km (39.11 km/h) 2003 Peter Van Petegem (Bel) 261 km (42.144 km/h) 2002 Johan Museeuw (Bel) 261 km (39.35 km/h) 2001 Servais Knaven (Ned) 254.5 km (39.19km/h) 2000 Johan Museeuw (Bel) 273 km (40.172 km/h) 1999 Andrea Tafi (Ita) 273 km (40.519 km/h) 1998 Franco Ballerini (Ita) 267 km (38.270 km/h) 1997 Frédéric Guesdon (Fra) 267 km (40.280 km/h) 1996 Johan Museeuw (Bel) 262 km (43.310 km/h) 1995 Franco Ballerini (Ita) 266 km (41.303 km/h) 1994 Andreï Tchmil (Mda) 270 km (36.160 km/h) 1993 Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle (Fra) 267 km (41.652 km/h) 1992 Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle (Fra) 267 km (41.480 km/h) 1991 Marc Madiot (Fra) 266 km (37.332 km/h) 1990 Eddy Planckaert (Bel) 265 km (34.855 km/h) 1989 Jean-Marie Wampers (Bel) 265 km (39.164 km/h) 1988 Dirk De Mol (Bel) 266 km (40.324 km/h) 1987 Eric Vanderaerden (Bel) -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Vol. 13.07 / August 2013

Vol. 13.07 News From France August 2013 A free monthly review of French news & trends On July 14, Friends of France Celebrate Bastille Day Around the United States © Samuel Tribollet © Samuel Tribollet © Samuel Tribollet Bastille Day, France’s national day, was celebrated on July 14. Known in France as simply “Le Quatorze Juillet,” the holiday marks the storming of Paris’s Bastille prison, which sparked the French Revolution and the country’s modern era. Above, Amb. François Delattre speaks to attendees at the French embassy. Story, p. 2 From the Ambassador’s Desk: A Monthly Message From François Delattre It’s been a typically hot July in Washington, but the simply “Le Quatorze Juillet.” The embassy hosted sev- weather hasn’t stopped excellent examples of French- eral events for the occasion, including a reception at the American partnership. splendid Anderson House in Washington D.C., organized inside To express support for French and American nutrition with the help of the Society of the Cincinnati, whom I programs, French Minister for Agrifood Industries Guil- would like to thank. Throughout the U.S., France’s consul- Current Events 2 laume Garot visited the 59th Annual Fancy Food Show in ates and public institutions partnered with local and pri- Bastille Day Fêted in 50 U.S. Cities New York City on July 1. vate groups to make Bastille Day 2013 a memorable fête Interview with the Expert 3 Continuing in French-American efforts, for French and American celebrants alike. Jean-Yves Le Gall, President of CNES Jean-Yves Le Gall, the new President of I’d like to take this opportunity to empha- France’s space agency, the Centre National size that celebrating Bastille Day is also a Special Report: Culture 4 d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), met in Wash- way to pay tribute to the universal values Tour de France Marks 100th Race ington with experts at NASA and the Na- of democracy and human rights at the Business & Technology 6 tional Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin- core of the French-American partnership. -

L'europe Francophone

L'Europe francophone La culture des loisirs: Les sports et les jeux (07.07.2010) Landeskundeseminar Dr. Claus D. Pusch FrankoMedia 2. Fachsemester SoSe 2010 Conférenciers: Rugby: Nicolas Bouffil Corrida: Insa Haag Tour de France: Kossiwa Ayena Le rugby à XV „Football is a gentleman's game played by ruffians. And rugby is a ruffian's game played by gentlemen.“ - Proverbe au Royaume Unis Video: intro rugby Les origines du rugby Les origines du rugby D'où vient le nom « Rugby »? William Webb Ellis * 24.11.1806 24.01.1872 Les origines du rugby ● « Rugby »: Ville anglaise du Warwickshire ● Jeu dérivée de la soule (ou siole) Les origines du rugby ● « Rugby »: Ville anglaise du Warwickshire ● Jeu dérivée de la soule (ou siole) ● Le rugby est au début un sport d'amateurs ● 1871: Fondation de la Rugby Football Union (RFU) L'histoire du rugby en France L'histoire du rugby en France ● 1906: Premier match de l'equipe de France ● 1910: La France est intégré dans le « Tournoi des cinq nations » ● Entre 1906 et 1914: Une seule victoire en 28 matchs internationaux: 02.01.1911 face à l'Ecosse (16 - 15) L'histoire du rugby en France ● 1930: Fondation de la FFR (Fédération Française du Rugby) ● 1931 – 1947: Exclusion de la France du Tournoi ● 1968: La France gagne son premier Grand Chelem L'histoire du rugby en France ● 1978: Intégration de la France dans l'IRB (International Rugby Board) ● 1987: Première coupe du monde en Nouvelle- Zélande et Australie (vainqueur: NZ) ● 1995: Professionalisation du rugby ● 2000: L'Italie entre le Tournoi L'histoire du -

9781781316566 01.Pdf

CONTENTS 1 The death of Fausto 7 Nairo Quintana is born 12 Maurice Garin is born 17 Van Steenbergen wins 27 Henri Pélissier, convict 37 The first Cima Coppi Coppi 2 January 4 February 3 March Flanders 2 April of the road, is shot dead 4 June 2 Thomas Stevens cycles 8 The Boston Cycling Club 13 First Tirenno–Adriatico 18 71 start, four finish 1 May 38 Gianni Bugno wins round the world is formed 11 February starts 11 March Milan–Sanremo 3 April 28 The narrowest ever the Giro 6 June 4 January 9 Marco Pantani dies 14 Louison Bobet dies 19 Grégory Baugé wins Grand Tour win is 39 LeMond’s comeback 3 Jacques Anquetil is 14 February 13 March seventh world title recorded 6 May 11 June born 8 January 10 Romain Maes dies 15 First Paris–Nice gets 7 April 29 Beryl Burton is born 40 The Bernina Strike 4 The Vélodrome d’Hiver 22 February underway 14 March 20 Hinault wins Paris– 12 May 12 June hosts its first six-day 11 Djamolidine 16 Wim van Est is born Roubaix 12 April 30 The first Giro d’Italia 41 Ottavio Bottecchia fatal race 13 January Abdoujaparov is born 25 March 21 Fiftieth edition of Paris– starts 13 May training ride ‘accident’ 5 The inaugural Tour 28 February Roubaix 13 April 31 Willie Hume wins in 14 June Down Under 19 January 22 Fischer wins first Hell of Belfast and changes 42 Franceso Moser is born 6 Tom Boonen’s Qatar the North 19 April cycle racing 18 May 19 June dominance begins 23 Hippolyte Aucouturier 32 Last Peace Race finishes 43 The longest Tour starts 30 January dies 22 April 20 May 20 June 24 The Florist wins Paris– 33 Mark Cavendish -

Tour De France in Düsseldorf 29.06.–02.07.2017 the Programme

GRAND DÉPART 2017 TOUR DE FRANce IN DüSSELDOrF 29.06.–02.07.2017 THE PROGRAMME CONTENTS conTenTs Profile: Geisel and Prudhomme .... 4 SATURDAY, 01.07 / DAY 3 ..........46 Countdown to the Tour.................... 6 Timetable / final of the The 104th Tour de France ............. 12 Petit Départ ...................................47 Service: Facts and figures ............ 14 Stage 1 event map ........................48 Service: Tour lexicon ..................... 18 Barrier-free access map ..............50 An overview of the programme .... 20 Traffic information and more .......52 On the route: Hotspots ................. 22 Cycle map for Saturday.................54 Our campaign: RADschlag ........... 26 Special: Along the route ...............56 Information for people Concert: Kraftwerk 3-D ................58 with disabilities ............................. 28 Public transport plan and SUNDAY, 02.07 / DAY 4 ................60 Rheinbahn app .............................. 30 Timetable.......................................61 ‘Festival du Tour’ by the Landtag .. 31 Stage 2 event map ........................62 Barrier-free access map ..............64 THURSDAY, 29.06 / DAY 1 ........... 32 Service: Neutralisation .................65 Team presentation event map ...... 34 Service: Route ...............................66 Sport: Introducing all the teams .. 35 Map of the entire region ...............68 Traffic information and more .......70 FRIDAY, 30.06 / DAY 2 .................. 43 Timetable / Schloss Benrath Special: Four insider tips..............72