Steven R. Morrison†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Grammy Award Winning Production Team Inks New Deal for Television

GRAMMY AWARD WINNING PRODUCTION TEAM INKS NEW DEAL FOR TELEVISION Van Nuys, CA - Mr. Marvin Williams, President/Founder of Big M Entertainment (a visual media company) and Mr. William Junebug Lee, Founder of The Bullets Production Team (a platinum music production company) will start pre-production on a new television series concept. William Lee and Marvin Williams have been bouncing ideas around for months trying to create the next big thing for television. The two will finally unveil their unique concept and editing techniques to television executives in a few months. The project details are subject to a strict veil of privacy which is not surprising at this stage. The Bullets Production Team founder William Lee is excited about moving into television and film, his company has consistently shown growth over the past thirteen years by achieving multi-platinum success including one Grammy nomination for (the Flo Rida Roots album) in 2009 and one win for (Love Is A Crime from the movie soundtrack Chicago) in 2004. Collectively the producers and writers have sold over sixty five-million records worldwide, the producers and writers consist of Greg Lawson, Klasic, Antwan, Christopher Spitfiya Lanier, Harold Scrap Fretty, Da' Hookas, Allan, and Baby Slim. some of there credits include: Roll - Flo Rida ft. Sean Kingston, Bonifide Hustler - Young Buck & 50Cent, Hit You Wit No Delay – Timbaland, Smile I'm Leaving – 50Cent, My Love Don't Cost A Thing - Jennifer Lopez, Love Is A Crime – Anastacia, Only God Can Judge Me - Tupac Shakur, Finally Here - Flo Rida, Just Because – Ginuwine, Make It Home - The Barber Shop 2 Soundtrack, Fame - B.O.B and many additional television and film credits . -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Adam Lambert American Idol Season 8 Live Performances (14 Songs

AdamLambert AmericanIdolSeason8LivePerformances(14songs) KissMedley(LiveAmericanIdol) TheAmericanIdolEP(13songs) AChangeIsGonnaCome(TheZodiacShowPerformance) APrayerForLife(TheTenCommandments) AsLongAsYou'reMine(WickedWednesdays) BeyondTheSky(TheCitizenVein) ComeHome(UprightCabaretPerformance) ComeToMe,BendToMe(Brigadoon) CrawlThruFire Crazy(UprightCabaretPerformance) Crazy DancingThroughLife(WickedLA) DustInTHeWind(UprightCabaretPerformance) Glamorize GottaGetThroughThis(UprightCabaretPerformance) HeavenOnTheMinds(BroadwayUnplugged) HowComeYouDon'tCallMeAnymore(UprightCabaretPerformance) ICan'tMakeYouLoveMe(UprightCabaretPerformance) IGotThis IJustLoveYou IntoTheDeep(TheTenCommandments) IsAnybodyListening(TheTenCommandmets) It'sSoHardToSayGoodbyeToYes(MtCarmelHighSchoolGraduationPerformance) KissAndTell(FonzerelliRadioEdit) KissAndTell MyConviction(HairEuropeanTour) NocturnalByTheMoon(TheCitizenVein) PopGoesTheCamera(FonzerelliClubMix) PopGoesTheCamera QuietDesperation RoughTrade(TheCitizenVein) TheCircle(TheCitizenVein) TheHornsOfJericho(TheTenCommandments) TurningUp(TheCitizenVein) What'sUp(UprightCabaretPerformance) You'veGotAFriend(WickedTourCabaretSF) Aerosmith(12/31/99LastShowOfTheCenturyOsakaDomeJapanSBD)(24songs) Aerosmith(8/28/75)(10songs) AerosmithQuilmesRock2007(17songs) AlexzJohnson Chicago(WeightUnreleased) Crawl(Demo) Don'tPullOffMyWings(Demo) Easy(WeightUnreleased) Golden(WeightUnreleased) FirstInLove(Demo) ISwearIWasNeverInLove(Demo) LostAndFound(Demo) lostAndFound(WeightUnreleased) Mailman(WeightUnreleased) RunningBack(Demo) -

49-99 Book Club in a Box TITLES AVAILABLE – NOVEMBER 2018 (Please Destroy All Previous Lists)

49-99 Book Club in a Box TITLES AVAILABLE – NOVEMBER 2018 (Please destroy all previous lists) FICTION, CONTEMPORARY AND HISTORICAL After You – by JoJo Moyes – (352 p.) – 15 copies Moyes’ sequel to her bestselling Me Before You (2012)—which was about Louisa, a young caregiver who falls in love with her quadriplegic charge, Will, and then loses him when he chooses suicide over a life of constant pain— examines the effects of a loved one’s death on those left behind to mourn. It's been 18 months since Will’s death, and Louisa is still grieving. After falling off her apartment roof terrace in a drunken state, she momentarily fears she’ll end up paralyzed herself, but Sam, the paramedic who treats her, does a great job—and she's lucky. Louisa convalesces in the bosom of her family in the village of Stortfold. When Louisa returns to London, a troubled 16-year-old named Lily turns up on her doorstep saying Will was her father though he never knew it because her mother thought he was "a selfish arsehole" and never told him she was pregnant. (Abbreviated from Kirkus) The Alchemist – by Paulo Coehlo – (186 p.) – 15 copies + Large Print "The boy's name was Santiago," it begins; Santiago is well educated and had intended to be a priest. But a desire for travel, to see every part of his native Spain, prompted him to become a shepherd instead. He's contented. But then twice he dreams about hidden treasure, and a seer tells him to follow the dream's instructions: go to Egypt to the pyramids, where he will find a treasure. -

Partner Név Jellemző Művek 100 BANDS PUBLISHING LUCKY YOU /#/ RINGER /#/ SIT DOWN /#/ KILLSHOT /#/ GOOD GUY FEAT JESSIE REYEZ

Partner név Jellemző Művek 100 BANDS PUBLISHING LUCKY YOU /#/ RINGER /#/ SIT DOWN /#/ KILLSHOT /#/ GOOD GUY FEAT JESSIE REYEZ 13 MOONS MUSIC BLOW /#/ KEEP PLAYING /#/ KEEP ME UP ALL NIGHT /#/ TOGETHER WE RUN /#/ BIGROOM BLITZ (RADIO MIX) 14 PRODUCTIONS SARL TIC TIC TAC /#/ OU SONT LES REVES /#/ PLACE DES GRANDS HOMMES /#/ QUI A LE DROIT /#/ JE SERAI LA POUR LA SUITE 1794 MUSIC AMERICAN BOOK OF SECRETS CUES /#/ AMERICA S BOOK OF SECRETS CUES /#/ BMOC /#/ LIMO HIP HOP VER 4 /#/ JOURNEY THROUGH TIME 1819 BROADWAY MUSIC DAYDREAM /#/ STORY S OVER (THE) /#/ STORY S OVER /#/ DAYDREAM (DJ NEWIK & STARWHORES REMIX) /#/ VADONATÚJ ÉRZÉS 1916 PUBLISHING MIDDLE (THE) /#/ HATE ME /#/ RUIN MY LIFE /#/ SLOW DANCE /#/ IF IT AIN T LOVE 23DB MUSIC RAPTURE /#/ HONEST SLEEP /#/ PALM DREAMS /#/ FLOWERS AND YOU /#/ DNA 24 HOUR SERVICE STATION ON THE LOOKOUT 2L E-SCORE UBI CARITAS /#/ SERENITY /#/ SNOW IN NEW YORK, FOR PIANO /#/ HUDSON /#/ ROXBURY PARK, FOR PIANO 2WAYTRAFFIC UK RIGHTS LTD TODAY S NAME - MAI JÁTÉKOSOK /#/ TODAY S NAMES /#/ WHAT IS THE ORDER - SORREND 3 WEDDINGS MUSIC SOMETHING ABOUT DECEMBER /#/ MAKE ME BELIEVE AGAIN /#/ HERE S TO NEVER GROWING UP /#/ JET BLACK HEART (START AGAIN) /#/ LET ME GO 360 MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD ONLY ONE /#/ IF YOU KNEW /#/ DON T BELONG /#/ HUMANICA /#/ MINIMAL LIFE 386MUSIC DON T LET GO /#/ VIOLET ALONE 3BEAT MUSIC LIMITED QUESTIONS /#/ MAN BEHIND THE SUN /#/ CONNECTION /#/ WHO'S LOVING YOU (PART 1) /#/ LINK UP 4 REAL MUSIC ANGELS LANDING /#/ EUGINA 2000 50 CENT MUSIC BEST FRIEND /#/ HATE IT OR LOVE IT /#/ HUSTLER S AMBITION -

The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families AUTHORS & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CAUGHT IN THE NET: The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families AUTHORS & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS American Civil Liberties Union (Lenora Lapidus, Namita Luthra & Anjuli Verma) Break the Chains: Communities of Color and the War on Drugs (Deborah Small) The Brennan Center at NYU School of Law (Patricia Allard & Kirsten Levingston) Andrea J. Ritchie also volunteered countless hours to drafting, editing, and giving the report a unified voice and an integrated analysis – all critical to the success and goals of the report. The authors also wish to acknowledge the many individuals who have been instrumen- tal in the process of writing and conceiving of Caught in the Net. The volunteer interns at each of our organizations were absolutely essential; they drafted research memos, checked and double checked citations, and remained throughout dedicated to the core mission and goals of the report – Much Thanks to Anita Khandelwal and Melanie Pinkert (ACLU DLRP), Leah Aden (ACLU WRP), Kimberly Lindsay and Rick Simon (Brennan Center), and Dominique Borges (Break the Chains). Staff at each of our organ- izations also brought their unique skills and insights to the report, making it a genuine expression of the diversity of our experiences and knowledge – Thank You, Stephanie Etienne, Renee Davis and Regina Eaton (Break the Chains), Graham Boyd and Allen Hopper (ACLU DLRP), Elizabeth Alexander (ACLU National Prison Project), and Chris Muller (Brennan Center). We could not have done it without you! Many others played critical roles in reading drafts and pointing -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

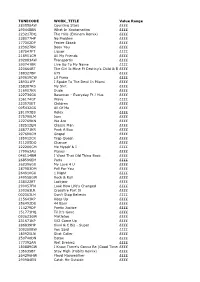

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

ACCIDENT, the D. Joseph Lovett USA 1998 97 Mins. Lovett

ACCIDENT, THE D. Joseph Lovett USA 1998 97 mins. Lovett Productions Documentary New England Premiere Director's Choice Presentation The filming of "The Accident" takes place over a quarter of a century. It is a personal film journey, and a search for the "real" lives if the filmmaker's parents amidst the kaleidoscope of stories and recollections o fsiblings who experienced radically different childhoods. The filmmaker travels back to the defining moment of his life, when, as a child, he was the only witness to his mother's death in a bizarre accident. This is the New England Premiere of this strong, personal film by Providence-native, Joe Lovett's critically acclaimed film. A must see. The Director will be present at the film screening. RISD Auditorium, Thursday, August 12, 7:00 pm A COEUR DECOUVERT (OPEN HEART) D. Denis Boivin Canada 1997 10 mins. Les Productions de Film Dionysis Inc. Drama United States Premiere Starring: Jean-Pierre Matte, Dorothée Berryman, Jack Robitaille An operating theater. A surgical team. A patient. A family. The open heart surgery is a success but the organ refuses to start again. Everything will be tried to bring Maurice back to life: from the conventional methods to the absurdist one. Provocative. RISD Auditorium, Sunday, August 15, 3:15 pm AFTER LUNCH D. Wendy Woodson USA 1998 22 mins. Present Company Experimental World Premiere "After Lunch" is a twenty-minute experimental narrative video that presents a surreal encounter between a man and woman in search of former and future lives during an afternoon lunch. The piece features Peter Schmitz and Aime Dowling as the man and woman and Kathy Couch as the waiter Max. -

2010 Trillium Are the First Poems That He Has Ever Written

Trillium2010 TrilliumVolume 31 • Spring 2010 A Literary Publication of the Glenville State College English Department Cover Photo by: Jade Nichols Editor Chris Summers Design Editor Dustin Crutchfield Editorial Staff Kari Hamric Rose Johnson Kaitlin Seelinger Mary Skidmore Whitney Stalnaker Jamie Stanley Jennifer Young Advisor Jonathan Minton Prince William There once was a magazine Compiled on a hill Full of art, poems, and stories That promised to thrill. One day the Advisor Hailed the Editor ‘tween classes. “We need your notes! An intro for the masses!” The Editor procrastinated. Another world, he was lost in. He avoided the notes so desperately He even read Jane Austen. Till one frigid night He sat at the screen And tried to write something Funny but clean. “A poem!” he cried. “I’ll call it Prince William! Since nothing else rhymes With our title of Trillium.” He typed and he typed In the late hours he toiled. Like Morgan’s aged coffee His creativity boiled. ‘Til at last this appeared, This intro to the journal That allows creativity to pop Like corn through a kernel. This poem is lousy. You’ll find better inside. Just trust when he says “Your editor tried.” Dedicated to Melty the Snowman, who inspired my first-ever poem, and to Mrs. Sallie Sturm, my 2nd grade teacher, who gave me the assignment to write it. Chris Summers, Editor, Trillium 2010 Poetry ...................................................................................................... 1 Wayne de Rosset, Lady in Waiting (a song) ........................................................ -

High Off Her Love – LOVE IS a DRUG

High off her love – LOVE IS A DRUG A comparative study of the use of love and sadness metaphors and their meaning in country and rap song lyrics Shona Lidström Student Vt 2017 Examensarbete för kandidatexamen, 15 hp Engelska Abstract This paper researches the use of conceptual metaphors in rap and country song lyrics. It looks specifically at conceptual metaphors for the concepts of LOVE and SADNESS, focusing on what source domains are proposed in each genre, what similarities there are in source domains between the genres and the style of language found in the linguistic expressions in the two genres. Song lists and lyrics were obtained from internet sites and then, using the Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP), linguistic expressions were identified which were then subjected to a qualitative analysis. Those relating to SADNESS and LOVE were grouped according to proposed source domains for comparison. The results show that there are similarities, and some differences in the source domains identified within the genres and that they have a wide variety of sub-domains. Concrete concepts common to both genres do not exhibit the same mapping of correspondences to the target domains. There is no discernible difference in the style of language used in the linguistic expressions of the two genres. Nevertheless, the rap expressions tend to be more in the present, dynamic and at times sexually provocative whereas in country expressions they tend to be more reflective, virtuous and at times, depressing. Keywords: conceptual metaphor, LOVE, SADNESS, lyrics, MIP Table of contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Previous Research ........................................................................................................... 8 2 Aim and research questions ..................................................................................