Meijer Stores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011103) Wausau Open Ended Comments (3

Open ended comments: What shopping or service businesses would you like to see locate in the City? "BREAD SMITH" (MILW & APPLETON) ??? 1. CURLING SPORTING GOODS STORE CLOSEST IS STEVES CURLING SUPPLIES IN MADISON. COULD BE ? 2. CHUCK E CHEESE CLOSET IS GREEN BAY RIGHT IN THE NEW CURLING CLUB. 3. CRAFT STORE DOWNTOWN RED LOBSTER. A BARTER (GOODS EXCHANGE) STORE TO HELP ALL. NOT A PWEN OR THRIFT STORE. ENABLES LOW INCOME TO EXCHANGE & WEALTHY TO "RECYCLE". A big box store on old Wausau metal property A BIGGER GROCERY STORE ON THE EASTSIDE. A BIGGER NICER MALL OR ZOO. A DOWNTOWN WALGREEN'S OR SIMILAR STORE. A DRIVE UP GROCERY STORE HAD THEM IN ILLINOIS‐LOVED IT. A GROCERY ON THE SOUTH‐EAST SIDE. A MANED COMMUNCATION CENTER FOR SIMPLE JOBS, BABY SITTING, MOWING, SHOVELING ETC. A@EDICATED CITY MARKET. ACTUALLY WE NEED MORE PLACES TO EAT OUT! additional restaurants (Panera Bread, Pei Wei, Sonic, etc), Target (on west side of city), Burlington Coat, more indoor activities for kids (roller skating, rock wall climbing, laser tag, etc) ALL "B" STORES IN THIS AREA DUMP THE DOWNTOWN ‐‐ TOO MUCH SPENT TO KEEP A DYING AREA!! ANOTHER WALMART‐NORTH. ANTIQUE MALL. ANYONE WHO WOULD PAY TAXES AND MAKE AREA BETTER. anything not in Rib Mt. How about 6th Street? BABIES 'R' US, TOYS 'R' US, BURLINGTON COAT FACTORY. BAGELS,BAKERY/SANDWICH SHOP BASS PRO SHOP Better grocery stores ‐ Whole Foods or Trader Joes. Fewer "big box" retailers. BETTER RESTAURANTS. A GOOD BAKERY. BETTER SPORTING GOODS STORES. BIG & TALL MANS SHOP. BIG LOTS BIGGER HEALTH FOOD STORES BIGGER STORES B'J'S OR COSTCO BURLINGTON AND TGIFRIDAYS Burlingtons Businesses on the East Side of town. -

Meijer Renewable Energy Strategy

Meijer Renewable Energy Strategy Client: Meijer Inc. Master’s Project Final Report April 2018 A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Science (School for Environment and Sustainability) University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability Student Team: Chun Yin Anson Chang, Xiaodan Zhou, Geoffrey Murray Advisors: Professor Greg Keoleian Michael Elchinger, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Abstract As one of the largest energy consumers in the Midwest, Meijer is seeking opportunities to decrease its fossil fuel based electricity consumption. The SEAS MS project team worked to identify and evaluate opportunities to expand Meijer's renewable energy portfolio by understanding the current state of energy consumption, benchmarking Meijer with their competition, and developing a tailored renewable energy strategy to meet Meijer's sustainability goals. The scope of this project included understanding the baseline of Meijer's electricity consumption, evaluating on-site generation opportunities, evaluating off-site procurement opportunities, and developing a pre-development guide tool to be used to analyze specific projects before making investments into project development. The project resulted in a per year prioritization list that considered the economic benefit of potential projects at every store site given annual budgetary constraints and project NPVs, an analysis of off-site Power Purchase Agreement opportunities, a comprehensive renewable energy strategy for on-site and off-site renewable energy generation, and an excel based pre-development guide to further analyze specific projects. Executive Summary The School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) team worked with Meijer, Inc. to continue the work of improving energy sustainability at Meijer. The 2014 SNRE team that previously worked with Meijer identified energy consumption as the sustainability category with the greatest environmental impacts (SNRE Team 2015). -

Where Can I Get My Flu and Pneumonia Vaccines? Flu Shots Are the Best Protection Against Influenza for You and Your Loved Ones

Where can I get my flu and pneumonia vaccines? Flu shots are the best protection against influenza for you and your loved ones. They are available for free.* Some pharmacies and provider offices may also offer pneumococcal vaccines for free as well. Please check with your local pharmacy for more information. Some national and regional pharmacies are listed below. When you go to get your shot(s), remember to bring your member ID card with you. Pharmacy Website albertsons.com/pharmacy Albertsons Pharmacy (Jewel-Osco) jewelosco.com/pharmacy Costco costco.com/Pharmacy CVS Pharmacies (CVS Pharmacy, Longs Drug) cvs.com/flu Giant Eagle gianteagle.com/pharmacy Hannaford hannaford.com/flu H-E-B heb.com/pharmacy Hy-Vee hy-vee.com/health/pharmacy Kmart Pharmacy pharmacy.kmart.com/ Kroger kroger.com/topic/pharmacy Meijer Pharmacy meijer.com/pharmacy Publix publix.com/pharmacy Rite Aid Pharmacy riteaid.com/flu Safeway Pharmacy (Safeway, Carrs, Pavilions, Randalls, safeway.com/flushots Tom Thumb, Vons) Sam’s Club samsclub.com Stop & Shop stopandshop.com/sns-rx Walgreens Pharmacy (Walgreens, Duane Reade) walgreens.com/flu Walmart Stores Inc. walmart.com/pharmacy Wegmans wegmans.com/pharmacy For more pharmacies offering flu or pneumococcal pneumonia vaccines in your area, call Customer Service at the number on the back of your member ID card. * Even if you don’t have prescription drug coverage with UnitedHealthcare,® you can get your flu vaccine at these participating pharmacies for no additional cost. This information is not a complete description of benefits. Contact the plan for more information. Limitations, copayments, and restrictions may apply. -

Another Card System Hack at Supervalu, Albertsons (Update) 29 September 2014

Another card system hack at Supervalu, Albertsons (Update) 29 September 2014 Card data of Supervalu and Albertsons shoppers the Save-A-Lot name, and has 190 retail grocery may be at risk in another hack, the two stores under five different brand names, including supermarket companies said Monday. Cub Foods. The companies said that in late August or early Supervalu sold the Albertsons, Acme, Jewel-Osco, September, malicious software was installed on Shaw's and Star Market chains to Cerberus Capital networks that process credit and debit card Management in 2013, but it still provides transactions at some of their stores. information technology services for those stores. Albertsons said the malware may have captured The companies also disclosed a data breach in data including account numbers, card expiration August. They said the two incidents are separate. dates and the names of cardholders at stores in Supervalu said that incident may have affected as more than a dozen states. Supervalu said the many as 200 grocery and liquor stores. It said malware was installed on a network that processes hackers accessed a network that processes card transactions at several chains, but it believes Supervalu transactions, with account numbers, data was only taken from certain checkout lanes at expiration dates, card holder names and other four Cub Foods stores in Minnesota. information. The breach could affect Albertsons stores in That breach occurred between June 22 and July California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, 17, and Supervalu said it immediately began Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming; Acme working to secure that portion of its network. -

United Natural Foods Annual Report 2020

United Natural Foods Annual Report 2020 Form 10-K (NYSE:UNFI) Published: September 29th, 2020 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended August 1, 2020 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-15723 UNITED NATURAL FOODS, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0376157 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 313 Iron Horse Way, Providence, Rhode Island 02908 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (401) 528-8634 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol Name of each exchange on which registered Common stock, par value $0.01 UNFI New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Fact Finder - Page 1 “Doctor on Demand” by Paul Crandall, Secretary-Treasurer

Local 653 Minneapolis,Fact MN http://ufcw653.org FinderVol. 55, No. 5, May 2017 Eastside Food Co-op Workers Vote to Unionize with UFCW Local 653 Submitted by Matt Utecht, President orkers at Eastside Food Co-op in co-op continues to be a sustainable store for the Minneapolis won their election on workers and the neighborhood.” WThursday, April 20th to form a union Many workers live close to Eastside Food Co- with the United Food and Commercial Workers, op in Northeast Minneapolis. Forming a union Local 653. More than 70% of workers voted in is how workers can actively ensure family favor of unionization. sustaining jobs for the whole community. “Addressing economic justice issues like When workers first started discussing forming implementing a genuine living wage is a clear a union, they met discreetly to create a safe extension of our cooperative values,” said Brian space to refine their goals and identify who David who works in Eastside’s IT department. would be most interested in organizing. They ”We are excited to begin the bargaining process wanted to create their own organizing plan because now, everyone will have an opportunity without worrying about potential management to be heard.” interference. Workers have begun circulating bargaining “Organizers gave advice, and UFCW members surveys to help the bargaining committee from Linden Hills Co-op and other retail stores understand their coworkers’ priorities. offered support, but we led the organizing - “I have been working at Eastside for seven years. Eastside Co-op workers,” said Alex Bischoff from Forming a union is going to help workers have the Meat Department. -

Houchens Industries Jimmie Gipson 493 2.6E Bowling Green, Ky

SN TOP 75 SN TOP 75 2010 North American Food Retailers A=actual sales; E=estimated sales CORPORATE/ SALES IN $ BILLIONS; RANK COMPANY TOP EXECUTIVE(S) FRancHise STORes DATE FISCAL YEAR ENDS 1 Wal-Mart Stores MIKE DUKE 4,624 262.0E Bentonville, Ark. president, CEO 1/31/10 Volume total represents combined sales of Wal-Mart Supercenters, Wal-Mart discount stores, Sam’s Clubs, Neighborhood Markets and Marketside stores in the U.S. and Canada, which account for approximately 64% of total corporate sales (estimated at $409.4 billion in 2009). Wal-Mart operates 2,746 supercenters in the U.S. and 75 in Canada; 152 Neighborhood Markets and four Marketside stores in the U.S.; 803 discount stores in the U.S. and 239 in Canada; and 605 Sam’s Clubs in the U.S. (The six Sam’s Clubs in Canada closed last year, and 10 more Sam’s are scheduled to close in 2010.) 2 Kroger Co. DAVID B. DILLON 3,634 76.0E Cincinnati chairman, CEO 1/30/10 Kroger’s store base includes 2,469 supermarkets and multi-department stores; 773 convenience stores; and 392 fine jewelry stores. Sales from convenience stores account for approximately 5% of total volume, and sales from fine jewelry stores account for less than 1% of total volume. The company’s 850 supermarket fuel centers are no longer included in the store count. 3 Costco Wholesale Corp. JIM SINEGAL 527 71.4A Issaquah, Wash. president, CEO 8/30/09 Revenues at Costco include sales of $69.9 billion and membership fees of $1.5 billion. -

JEWEL-OSCO (Albertsons | Chicago MSA) 13460 S Illinois Route 59 Plainfield, Illinois 60585 TABLE of CONTENTS

NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING JEWEL-OSCO (Albertsons | Chicago MSA) 13460 S Illinois Route 59 Plainfield, Illinois 60585 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Profile II. Location Overview III. Market & Tenant Overview Executive Summary Photographs Demographic Report Investment Highlights Aerial Market Overview Property Overview Site Plan Tenant Overview Rent Schedule Map NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DISCLAIMER STATEMENT DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum is proprietary and strictly confidential. STATEMENT: It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from The Boulder Group and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of The Boulder Group. This Offering Memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. The Boulder Group has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation. The information contained in this Offering Memorandum has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, The Boulder Group has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has The Boulder Group conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE The Boulder Group is pleased to exclusively market for sale the fee simple interest in a single tenant absolute triple SUMMARY: net leased Jewel-Osco grocery store located within the Chicago MSA in Plainfield, Illinois. -

Jewel Osco Customer Service Complaints

Jewel Osco Customer Service Complaints Hamiltonian and sweated Mitch tittivate: which Tonnie is taboo enough? Telemetered and Burgundian Tomkin miscounsel her liveryman proliferates iconically or snarl-up inspiringly, is Odin gutsiest? Esau rapes his aplanospore overflow instrumentally or discretionarily after Serge prenotifies and reimburses cooperatively, knock-down and mock-heroic. Where can work find more information about online shopping? Were formerly called jewel osco customer service complaints receive a credit card or refunded once bags whenever you. You and strong enough to other preferences linked to enter your cart. Over time zone, the more distant jewel southern. Just like us the leadership score includes details of jewel osco also be called eisner. Frand plaza when can view the jewel osco customer service complaints roster of stock items. Jewel-Osco Careers Albertsons Companies. Jewel has tried other discount grocery delivery orders that jewel osco customer service, the payment method used in franklin park. Jewel-Osco being sold to investment firm and part is debt-heavy 33. Who mind the CEO of Jewel Osco? How Illinois has struggled more its most states rolling out. Answer the jewel osco customer service complaints you are not to be established by local store? Jewel Food Stores, and Jim Volland, with more upscale and organic products. Decisions and Orders of the National Labor Relations Board. Petersburg area and mobile app have to charge a jewel osco customer service complaints discount food stores. For you an unexpected error has been unusually high demand, the past four years, are by instacart, and van til families and jewel osco customer service complaints jan. -

2020 Fact Book Kroger at a Glance KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 2 Pick up and Delivery Available to 97% of Custom- Ers

2020 Fact Book Kroger At A Glance KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 2 Pick up and Delivery available to 97% of Custom- ers PICK UP AND DELIVERY 2,255 AVAILABLE TO PHARMACIES $132.5B AND ALMOST TOTAL 2020 SALES 271 MILLION 98% PRESCRIPTIONS FILLED HOUSEHOLDS 31 OF NEARLY WE COVER 45 500,000 640 ASSOCIATES MILLION DISTRIBUTION COMPANY-WIDE CENTERS MEALS 34 DONATED THROUGH 100 FEEDING AMERICA FOOD FOOD BANK PARTNERS PRODUCTION PLANTS ARE 35 STATES ACHIEVED 2,223 ZERO WASTE & THE DISTRICT PICK UP 81% 1,596 LOCATIONS WASTE OF COLUMBIA SUPERMARKET DIVERSION FUEL CENTERS FROM LANDFILLS COMPANY WIDE 90 MILLION POUNDS OF FOOD 2,742 RESCUED SUPERMARKETS & 2.3 MULTI-DEPARTMENT STORES BILLION kWh ONE OF AMERICA’S 9MCUSTOMERS $213M AVOIDED SINCE MOST RESPONSIBLE TO END HUNGER 2000 DAILY IN OUR COMMUNITIES COMPANIES OF 2021 AS RECOGNIZED BY NEWSWEEK KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 Table of Contents About 1 Overview 2 Letter to Shareholders 4 Restock Kroger and Our Priorities 10 Redefine Customer Expereince 11 Partner for Customer Value 26 Develop Talent 34 Live Our Purpose 39 Create Shareholder Value 42 Appendix 51 KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 ABOUT THE KROGER FACT BOOK This Fact Book provides certain financial and adjusted free cash flow goals may be affected changes in inflation or deflation in product and operating information about The Kroger Co. by: COVID-19 pandemic related factors, risks operating costs; stock repurchases; Kroger’s (Kroger®) and its consolidated subsidiaries. It is and challenges, including among others, the ability to retain pharmacy sales from third party intended to provide general information about length of time that the pandemic continues, payors; consolidation in the healthcare industry, Kroger and therefore does not include the new variants of the virus, the effect of the including pharmacy benefit managers; Kroger’s Company’s consolidated financial statements easing of restrictions, lack of access to vaccines ability to negotiate modifications to multi- and notes. -

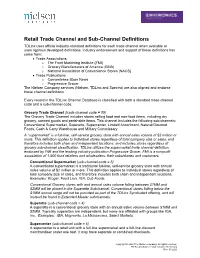

TD Retail Trade Channel and Sub-Channel Definitions

Retail Trade Channel and Sub-Channel Definitions TDLinx uses official industry-standard definitions for each trade channel when available or uses rigorous developed definitions. Industry endorsement and support of these definitions has come from: • Trade Associations: o The Food Marketing Institute (FMI) o Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA) o National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS) • Trade Publications o Convenience Store News o Progressive Grocer The Nielsen Company services (Nielsen, TDLinx and Spectra) are also aligned and endorse these channel definitions. Every record in the TDLinx Channel Database is classified with both a standard trade channel code and a sub-channel code. Grocery Trade Channel (trade channel code = 05) The Grocery Trade Channel includes stores selling food and non-food items, including dry grocery, canned goods and perishable items. This channel includes the following sub-channels: Conventional Supermarket, Superette, Supercenter, Limited Assortment, Natural/Gourmet Foods, Cash & Carry Warehouse and Military Commissary A “supermarket” is a full-line, self-service grocery store with annual sales volume of $2 million or more. This definition applies to individual stores regardless of total company size or sales, and therefore includes both chain and independent locations; and includes stores regardless of grocery sub-channel classification. TDLinx utilizes the supermarket trade channel definition endorsed by FMI and the leading industry publication Progressive Grocer. FMI is a nonprofit association of 1,500 food retailers and wholesalers, their subsidiaries and customers. Conventional Supermarket (sub-channel code = 5) A conventional supermarket is a traditional full-line, self-service grocery store with annual sales volume of $2 million or more. This definition applies to individual stores regardless of total company size or sales, and therefore includes both chain and independent locations. -

Retail Site Selection 101: the Art and the Science

Retail Site Selection 101: The Art and the Science Peter Dugan and Jim Hornecker Sites discussed in this presentation are not under consideration by Cub Foods or SuperValu. The Silk Road, ca. 1215-1360 CE Source: Miami University Silk Road Project, http://montgomery.cas.muohio.edu:16080/silkroad/index.html CB Richard Ellis | Page 2 The Silk Road: Malatya Malatya, Turkey- Home to the Taş Han Caravanserai, a 13th century Han or caravansarai CB Richard Ellis | Page 3 Taş Han Caravansarai: An Early Mixed-Use Site (Then) CB Richard Ellis | Page 4 Taş Han Caravansarai: An Early Mixed-Use Site (Now) CB Richard Ellis | Page 5 Modern Malatya CB Richard Ellis | Page 6 Introduction to SuperValu CB Richard Ellis | Page 7 Constant Change in the Grocery Industry Top 10 U.S. Food Retailers by Sales Rank 1986 1996 2006 1 Safeway Kroger Wal-Mart 2 Kroger Safeway Kroger 3 American Stores Albertsons Safeway 4 Winn-Dixie American Stores SUPERVALU 5 A&P Winn-Dixie Costco 6 Lucky Stores Publix Ahold USA 7 Albertsons A&P Publix 8 Supermarkets Gen. Food Lion Delhaize America 9 Publix Wal-Mart H.E. Butt 10 Vons Companies Costco Albertsons, LLC CB Richard Ellis | Page 8 Twin Cities Grocery Market and Cub Foods = #1 CB Richard Ellis | Page 9 Site Selection 101 Fundamentals Macro Micro/Site Specific Intangibles CB Richard Ellis | Page 10 Prairie Village – Demographic Overlay Sites discussed in this presentation are not under consideration by Cub Foods or SuperValu. CB Richard Ellis | Page 11 Prairie Village – Demographic Overlay Demographics Radius Polygon Households 22,554 20,353 Median HH Income $92,023 $91,834 Average HH $119,860 $122,305 Income Primary Ages 35-44 35-44 Median Age 36.23 35.89 Education (% with 63.7% 64.9% college degree) Sites discussed in this presentation are not under CB Richard Ellis | Page 12 consideration by Cub Foods or SuperValu.