Congressional Control of Foreign Assistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congress' Power of the Purse

Congress' Power of the Purse Kate Stitht In view of the significance of Congress' power of the purse, it is surprising that there has been so little scholarly exploration of its contours. In this Arti- cle, Professor Stith draws upon constitutional structure, history, and practice to develop a general theory of Congress' appropriationspower. She concludes that the appropriationsclause of the Constitution imposes an obligation upon Congress as well as a limitation upon the executive branch: The Executive may not raise or spend funds not appropriatedby explicit legislative action, and Congress has a constitutional duty to limit the amount and duration of each grant of spending authority. Professor Stith examinesforms of spending authority that are constitutionally troubling, especially gift authority, through which Congress permits federal agencies to receive and spend private contri- butions withoutfurther legislative review. Other types of "backdoor" spending authority, including statutory entitlements and revolving funds, may also be inconsistent with Congress' duty to exercise control over the size and duration of appropriations.Finally, Professor Stith proposes that nonjudicial institu- tions such as the General Accounting Office play a larger role in enforcing and vindicating Congress' power of the purse. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF APPROPRIATIONS 1346 A. The Constitutional Prerequisitesfor Federal Gov- ernment Activity 1346 B. The Place of Congress' Power To Appropriate in the Structure of the Constitution 1348 C. The Constitutional Function of "Appropriations" 1352 D. The Principlesof the Public Fisc and of Appropria- tions Control 1356 E. The Power to Deny Appropriations 1360 II. APPROPRIATIONS CONTROL: THE LEGISLATIVE FRAME- WORK 1363 t Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School. -

424 Public Law 87-194 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House Of

424 PUBLIC LAW 87-194-SEPT. 1, 1961 [75 ST AT. Public Law 87-194 September 1, 1961 AN ACT [H. R. 7809] To improve the active duty promotion opportunity of Air Force ofllcers from the grade of major to the grade of lieutenant colonel. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of tJie Air Force offl- United States of America in Congress assembled^ That, during the period beginning on the date of enactment of this Act and ending at the close of June 30, 1963, any authorized strength prescribed for the grade of lieutenant colonel by or under section 8202 of title 10, 70A Stat. 498. United States Code, may be exceeded by not more than four thousand. Approved September 1, 1961. Public Law 87-195 September 4. 1961 AN ACT [S.1983] To promote the foreign policy, security, and general welfare of the United States by assisting peoples of the world in their efforts toward economic development and internal and external security, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the The Foreign As- United States of America in Congress assembled^ sistance Act of 1961. Post, p. 719. PART I CHAPTER 1—SHORT TITLE AND POLICY Act for Interna tional Develop- SEC. 101. SHORT TITLE.—This part may be cited as the "Act for ment of 1961. International Development of 1961". SEC. 102. STATEMENT OF POLICY.—It is the sense of the Congress that peace depends on wider recognition of the dignity and interde pendence of men, and survival of me institutions in the United States can best be assured in a worldwide atmosphere of freedom. -

The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice

The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice Updated March 8, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42699 The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice Summary This report discusses and assesses the War Powers Resolution and its application since enactment in 1973, providing detailed background on various cases in which it was used, as well as cases in which issues of its applicability were raised. In the post-Cold War world, Presidents have continued to commit U.S. Armed Forces into potential hostilities, sometimes without a specific authorization from Congress. Thus the War Powers Resolution and its purposes continue to be a potential subject of controversy. On June 7, 1995, the House defeated, by a vote of 217-201, an amendment to repeal the central features of the War Powers Resolution that have been deemed unconstitutional by every President since the law’s enactment in 1973. In 1999, after the President committed U.S. military forces to action in Yugoslavia without congressional authorization, Representative Tom Campbell used expedited procedures under the Resolution to force a debate and votes on U.S. military action in Yugoslavia, and later sought, unsuccessfully, through a federal court suit to enforce presidential compliance with the terms of the War Powers Resolution. The War Powers Resolution (P.L. 93-148) was enacted over the veto of President Nixon on November 7, 1973, to provide procedures for Congress and the President to participate in decisions to send U.S. Armed Forces into hostilities. Section 4(a)(1) requires the President to report to Congress any introduction of U.S. -

Congress and the Supersonic Transport, 1960-1971 by John

Congress and the supersonic transport, 1960-1971 by John Marion Bell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Montana State University © Copyright by John Marion Bell (1974) Abstract: Aviation state-of-the-art advances in the 1940's and 1950's paved the way for development of a commercial SST in the 1960's. Military aviation advances were translated directly into subsonic transports and it was felt that the next step in progress would be the SST. Through military programs and basic research by NACA, the United States government aided the development of a commercial SST even before undertaking an active SST program in the 1960's. Foreign governments were also at work on SST's and when the British and French merged their development programs in 1962 the United States was spurred by their competition. President Kennedy announced an active program in June, 1963 a day following Pan Am's order of Anglo-French SST's. There was little opposition to the airplane at first; what little there was was based on the aircraft's unavoidable sonic boom. A design competition was conducted by the FAA to select the best possible American design. Boeing was selected the winner in 1966 on the basis of a radical, swing-wing design. The program then entered a two-prototype development stage. Boeing soon ran into development problems and in 1968 abandoned its swing-wing in favor of a conventional fixed-wing. The airplane's problems were also complicated by the great increase in cost of development as well as a growing opposition based on the possible negative environmental impact of the SST. -

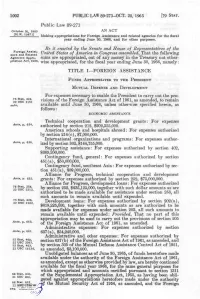

79 Stat. 1002

1002 PUBLIC LAW 89-273-OCT. 20, 1965 [79 STAT. Public Law 89-273 October 20, 1965 AN ACT [H. R. 10871] Making appropriations for Foreign Assistance and related agencies for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1966, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Eepresentatives of the Foreign Assist ance and Related United States of America in Congress assembled, That the following Agencies Appro sums are appropriated, out of any money in the Treasury not other priation Act, 1966. wise a])propriated, for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1966, namely: TITLE I—FOREIGN ASSISTANCE FUNDS APPROPRIATED TO THE PRESIDENT MUTUAL DEFENSE AND DEVELOPMENT For expenses necessary to enable the President to carry out the pro 75 Stat. 424, 22 use 2151 visions of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, to remain note. available until June 30, 1966, unless otherwise specified herein, as follows: ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE Technical cooperation and development grants: For expenses Ante, p. 654. authorized by section 212, $202,355,000. American schools and hospitals abroad: For expenses authorized by section 214(c), $7,000,000. International organizations and programs: For expenses author Ante, p. 656. ized by section 302, $144,755,000. Supporting assistance: For expenses authorized by section 402, $369,200,000. Contingency fund, general: For expenses authorized by section 451(a), $50,000,000. Contingency fund, southeast Asia: For expenses authorized by sec tion 451(a), $89,000,000. Alliance for Progress, technical cooperation and development Ante, p. 655. grants: For expenses authorized by section 252, $75,000,000. -

The Boland Amendment and Report, 1983 in Late 1982 the U.S

The Boland Amendment and Report, 1983 In late 1982 the U.S. Congress passed an amendment to a bill that restricted U.S. spending in Nicaragua. The amendment, proposed by Massachusetts Representative, Edward Boland, said that “None of the funds provided in this Act may be used by the Central Intelligence Agency or the Department of Defense to furnish military equipment, military training or advice, or other support for military activities, to any group or individual, not part of a country’s armed forces, for the purposes of overthrowing the Government of Nicaragua or provoking a military exchange between Nicaragua and Honduras.” This report explained Boland’s view of the Nicaraguan situation, and it included a new amendment that extended the restriction. Report of Mr. Boland The Committee’s action on H.R. 2760 [to amend the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1983 to prohibit United States support for military or paramilitary operations in Nicaragua and to authorize assistance, to be openly provided to governments of countries in Central America, to interdict the supply of military equipment from Nicaragua and Cuba to individuals, groups, organizations or movements seeking to overthrow governments of countries in Central America] comes at a time when U.S. foreign policy towards Central America is at the forefront of discussion in the Congress and throughout the nation. Attention has been focused on events in that troubled region not only because of their daily depiction in news reports but because of the President’s April 27 address to a joint session of the Congress. As the President so forcefully noted, Central America has a strategic importance to the United States, yet some Central America nations friendly to the United States are now under attack. -

Copyrighted Material

bindex.qxd 6/9/06 10:19 AM Page 307 INDEX ABC News, 98 Aspin, Les, 235 Abraham Lincoln, 272 atomic bombs Abrams, Creighton, 147, 148, 155, 158–159 Hiroshima and, 33, 44–45 Abrams, Elliott, 203–204 Korean War and, 42 Abu Ghraib, 277–280 mutual assured destruction (MAD) and, 48 Acheson, Dean, 39 See also nuclear weapons Cuban Missile Crisis and, 84, 87 Korean War and, 35, 36, 39, 41, 44 Baathist regime, 272. See also Iraq Vietnam War and, 131–132 Bacon, Augustus O., 23 Adams, John, 14 Baker, James, 190, 231, 237 Adams, John Quincy, 17 Panama, 223 Adams, Sherman, 55 Yugoslavia and, 237 Adelman, Kenneth, 261 Balaguer, Joaquin, 129 Adenauer, Konrad, 94 Balkans, 237–242, 245 Afghanistan, 287–288 Ball, George, 105 Carter and, 187–189 Cuban Missile Crisis, 78 Clinton and, 243, 244, 245 Vietnam War, 120–121, 124, 132 George H. W. Bush and, 222, 223–224 Barzani, Mustafa, 184 George W. Bush and, 249, 252–256, 257, Batista, Fulgencio, 61–62 269, 280 Battle of New Orleans, 15 Reagan and, 191, 193, 200–201 Bay of Pigs, 64–71, 77, 85, 235 Africa, 233–234, 245. See also individual names Beckwith, Bob, 254 of countries Beecher, William, 149, 159 Aidid, Mohammed Farrah, 234, 236 Begin, Menachem, 193 Allen, Richard, 190 Beirut. See Lebanon Allende Gossens, Salvador, 164–166 Bennett, Tapley, 129 al-Qaeda, 243–245, 249–253 Berger, Sandy, 234, 244, 249 Iraq and, 250–256, 257–269, 274–276 Berlin Wall, 34, 221 prisoners of United States and, 276–280 Biden, Joseph, 248–249 September 11 attacks and, 253–256, 269 Bin Laden, Osama, 227, 243–245, 248–256 Al-Shiraa -

Background on the Iran-Contra Affair

Educational materials developed through the Baltimore County History Labs Program, a partnership between Baltimore County Public Schools and the UMBC Center for History Education. RS#01: Background on the Iran-Contra Affair Read the background information on the Iran-Contra affair and highlight the major events and actors. Take notes on when the events occurred and in what order. During the administrations of President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) and President Ronald Reagan (1981- 1989), the United States witnessed an increase in Communist uprisings and governments in Latin America, as well as turmoil and the growth of Islamic extremism in parts of the Middle East. In 1979 in the Middle Eastern country of Iran, a revolution, led by the Islamic religious leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, overthrew Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Ayatollah Khomeini sought to remove all Western influences within the country and establish an Islamic Republic. In an act of deliberate aggression against the United States, the new Iranian government captured and held 52 Americans for 444 days. Many historians agree that the inability of the Carter administration to resolve the crisis was instrumental to the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Negotiations were, in fact, secretly underway, but the release of the hostages would not come until Reagan was sworn into office in January 1981. The United States broke off relations with Iran and instituted a series of economic sanctions in an attempt to weaken the theocratic government. In Central America in July 1979, a Cuban-backed Marxist organization, called the Sandinistas, took control of the government of Nicaragua. Communism and the Soviet Union appeared to be an ever-growing challenge to the United States and to the new Reagan administration. -

88 Stat. 1795

88 STAT. ] PUBLIC LAW 93-559-DEC. 30, 1974 1795 Public Law 93-559 AN ACT December 30, 1974 To amend the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, and for other purposes. [s.3394] Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the Foreign Assist United States of America in Congress assemhled^ That this Act may ance Act of 1974., be cited as the "Foreign Assistance Act of 1974". "'•j'a" use 2*151 note. FOOD AND JSrUTRITION SEC. 2. Section 103 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 is 22 use 21Sla. amended— (1) by inserting the subsection designation "(a)" immediately before "In"; (2) by striking out "$291,000,000 for each of the fiscal years 1974 and 1975" and inserting in lieu thereof "$291,000,000 for the fiscal year 1974, and $500,000,000 for the fiscal year 1975"; and (3) by adding at the end thereof the following: "(b) The Congress finds that, due to rising world food, fertilizer, and petroleum costs, human suffering and deprivation are growing in , . , the poorest and most slowly developing countries. The greatest poten tial for significantly expanding world food production at relatively low cost lies in increasing the productivity of small farmers who con stitute a majority of the nearly one billion people living in those countries. Increasing the emphasis on rural development and expanded food production in the poorest nations of the developing world is a matter of social justice as well as an important factor in slowing the rate of inflation in the industrialized countries. In the allocation of funds under this section, special attention should be given to increasing agricultural production in the countries with per capita / incomes under $300 a year and which are the most severely affected by sharp increases in worldwide commodity prices." CEILING ON FERTILIZERS TO SOUTH VIETNAM SEC. -

The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice

The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice Updated March 8, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42699 The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice Summary This report discusses and assesses the War Powers Resolution and its application since enactment in 1973, providing detailed background on various cases in which it was used, as well as cases in which issues of its applicability were raised. In the post-Cold War world, Presidents have continued to commit U.S. Armed Forces into potential hostilities, sometimes without a specific authorization from Congress. Thus the War Powers Resolution and its purposes continue to be a potential subject of controversy. On June 7, 1995, the House defeated, by a vote of 217-201, an amendment to repeal the central features of the War Powers Resolution that have been deemed unconstitutional by every President since the law’s enactment in 1973. In 1999, after the President committed U.S. military forces to action in Yugoslavia without congressional authorization, Representative Tom Campbell used expedited procedures under the Resolution to force a debate and votes on U.S. military action in Yugoslavia, and later sought, unsuccessfully, through a federal court suit to enforce presidential compliance with the terms of the War Powers Resolution. The War Powers Resolution (P.L. 93-148) was enacted over the veto of President Nixon on November 7, 1973, to provide procedures for Congress and the President to participate in decisions to send U.S. Armed Forces into hostilities. Section 4(a)(1) requires the President to report to Congress any introduction of U.S. -

The Use of Conditions in Foreign Relations Legislation

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 7 Number 2 Spring Article 3 May 2020 The Use of Conditions in Foreign Relations Legislation Thomas A. Balmer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Thomas A. Balmer, The Use of Conditions in Foreign Relations Legislation, 7 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 197 (1978). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. The Use of Conditions in Foreign Relations Legislation THOMAS A. BALMER* I. INTRODUCTION The very heart of our identity as a nation is our firm commitment to human rights. We stand for human rights because we believe that the purpose of government is to protect the well-being of its citizens. The world must know that in support of human rights the United States will stand firm. We expect no quick or easy results, but there has been significant movement toward greater freedom and humanity in several parts of the world. Thousands of political prisoners have been freed. The leaders of the world-even our ideological adversaries-now see that their atti- tude toward fundamental human rights affects their standing in the international community and their relations with the United States.I In his first State of the Union Address, President Carter thus reaffirmed the human rights position that had played an important part in his presidential campaign. -

Beyond Assistance: the HELP Commission Report on Foreign

BEYOND ASSISTANCE THE HELP COMMISSION REPO rt ON FO R EIGN ASSIS ta N C E RE F O R M Helping to Enhance the Livelihood of People around the Globe Congresswoman Jennifer Dunn, who wanted America to be known not just for its strength, but for its compassion, was an invaluable member of the HELP Commission for twenty months. Jennifer’s grace distinguished and defined her life; she honored our Commission with her friendship and her service; and our report is dedicated to her memory. Members of the HELP Commission, and How They Voted The Commission approved the following report by a vote of 19 to 1. Commissioners Voting in the Affirmative: The Honorable Mary K. Bush, Chairman The Honorable Dr. Carol C. Adelman, Vice Chairman Leo Hindery, Jr., Vice Chairman Steven K. Berry, Esq. Jerome F. Climer Dr. Nicholas N. Eberstadt Glenn E. Estess, Sr. Lynn C. Fritz Benjamin K. Homan The Honorable Walter H. Kansteiner III Thomas C. Kleine, Esq. William C. Lane C. Payne Lucas Dr. Martin L. LaVor The Honorable Robert H. Michel Eric G. Postel Gayle E. Smith David A. Williams Alonzo L. Fulgham, Representative of the USAID Administrator Commissioners Opposing: Dr. Jeffrey D. Sachs 3 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 7 FINDINGS..............................................................................................................................................9 The world has changed and U.S. assistance programs have not kept pace..............................................9