Feature Names and Identity in Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zimbabwe's Liberation Struggle Era Conflicts and the Pitfalls Of

TITLE: Zimbabwe’s Liberation Struggle Era Conflicts and the Pitfalls of Reconciliation after Independence: A Case Study of Bikita District 1976-2013. By Dorothy Goredema A Thesis submitted to the Midlands State University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. Faculty of Arts Midlands State University 2015 i Declaration I Dorothy Goredema, hereby declare that this thesis for the Doctor of Philosophy in History at the Midlands State University, hereby submitted by me, has not been previously submitted for a degree at this or any other institution, and that this is my work in design and execution, and all reference materials contained herein have been duly acknowledged. ………………………………………… …………………………………….. Signature Date I hereby certify that the above statement is correct. Main Supervisor, Prof. N.Bhebe………………. …. ………………………… Signature Date Co-Supervisor, Dr.T.M Mashingaidze…………….. …………………………… Signature Date i Acknowledgements I owe a special debt of gratitude to my main supervisor, Professor Ngwabi Bhebe, and Dr. T.M Mashingaidze. Firstly, Professor Bhebe, I will be forever indebted to you. Despite your busy schedule as Vice-Chancellor of a university, you would always make time for me as a student and for my work. You took an interest in my topic and gave direction to many of my disjointed ideas that marked the genesis of the study. You continuously assessed my work, giving me feedback on time and went an extra mile to facilitate co-supervisors and funds that supported my work. I will forever be indebted to your efficiency, wise counsel and critical mind. Thank you Professor for your mentorship and intellectual support. -

Challenges Faced by Rural People in Mitigating the Effects of Climate Change in the Mazungunye Communal Lands, Zimbabwe

Jàmbá - Journal of Disaster Risk Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-845X, (Print) 1996-1421 Page 1 of 9 Original Research Challenges faced by rural people in mitigating the effects of climate change in the Mazungunye communal lands, Zimbabwe Authors: The phenomenon of climate change is one of the most contested and debated concepts 1 Louis Nyahunda globally. Some governments still deny the existence of climate change and its impact on Happy M. Tirivangasi2 rural–urban areas around the world. However, the effects of climate change have been visible Affiliations: in rural Zimbabwe, with some communities facing food insecurity, water scarcity and loss of 1Department of Social Work, livestock. Climate change has impacted negatively on agriculture, which is the main source University of Limpopo, of livelihood in Zimbabwe’s rural communities. This study aims at exploring challenges South Africa faced by rural people in mitigating the effects of climate change in the Mazungunye 2Department of Sociology community, Masvingo Province, in Zimbabwe. The objectives of the study were to identify and Anthropology, University the challenges that impede effective adaptation of rural people to climate change hazards and of Limpopo, South Africa to examine their perceptions on how to foster effective adaptation. The researchers conducted Corresponding author: a qualitative research study guided by descriptive and exploratory research designs. Happy Tirivangasi, Purposive sampling was employed to draw the population of the study. The population mathewtirivangasi@gmail. sample consisted of 26 research participants drawn from members of the community. Data com was collected through in-depth individual interviews and focus group discussions. Thematic Dates: content analysis was used to analyse data. -

Masvingo Province

School Level Province Ditsrict School Name School Address Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA FASHU SCH BIKITA MINERALS CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA MAMUTSE SECONDARY MUCHAKAZIKWA VILLAGE CHIEF BUDZI BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIRIVENGE MUPAMHADZI VILLAGE WARD 12 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita BUDIRIRO VILLAGE 1 WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHENINGA B WARD 2, CHF;MABIKA, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIKWIRA BETA VILLAGE,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE,WARD 16 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHINYIKA VILLAGE 23 DEVURE WARD 26 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIPENDEKE CHADYA VILLAGE, CHF ZIKI, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRIMA RUGARE VILLAGE WARD 22, CHIEF;MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRUMBA TAKAWIRA VILLAGE, WARD 9, CHF; MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHISUNGO MBUNGE VILLAGE WARD 21 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIZONDO CHIZONDO HIGH,ZINDOVE VILLAGE,WARD 2,CHIEF MABIKA Secondary Masvingo Bikita FAMBIDZANAI HUNENGA VILLAGE Secondary Masvingo Bikita GWINDINGWI MABHANDE VILLAGE,CHF;MUKANGANWI, WRAD 13, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUDADISA ZINAMO VILLAGE, WARD 20,CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUSHINGIRIRA MUKANDYO VILLAGE,BIKITA SOUTH, WARD 6 Secondary Masvingo Bikita MACHIRARA CHIWA VILLAGE, CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANGONDO MUSUKWA VILLAGE WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANUNURE DEVURE RESETTLEMENT VILLAGE 4A CHIEF BUDZI Secondary Masvingo Bikita MARIRANGWE HEADMAN NEGOVANO,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MASEKAYI(BOORA) -

Seminar-: 16 June 1973 UNIVERSITY 0F RHODESIA

Seminar-: 16 June 1973 UNIVERSITY_ 0F_ RHODESIA : DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HENDERSON SEMINAR NO. 23 THEJISE _OF__THE_UUtnA CONFEDERACY^ H700_-_1800: A STUDY OF AN AFRICAN STATE IN SOUTHERN ZAMBEZI A. - - - “ - " R.M'.O. KITETWA This paper attempts to cover the history of the whole pre- 1800 Duma Confederacy. (1) I say attempts because it is written on the strength of oral traditions collected by the writer in only one d is tric t, B ikita ; (2) yet the Duma are found in several other d is tric ts : Chiredzi, Gutu, Fort Victoria, Zaka formerly Ndanga, and Mr H.E. Sumner includes Chibi as well.(3) Furthermore, there is the great problem of the in a va ila b ility of documentary evidence relevant to the history of the Duma. However, as far as Duma history is concerned, the Bikita d is tric t is the most important for the following reasons: ( 1) this is where the proto - Duma lived and the name Duma came into being; (2) this is where the headquarters of the Duma Confederacy were established on the small Mandara h i ll; and (3) this is where the Big Four Duma chiefs with dynastic titles of Mukanganwi, Mazungunye, Ziki and Mabika were and are s t ill resident. The Duma are a Shona - speaking people who liv e in the V ictoria Province. They are today the ruling aristocracy of the study area(4) except the Rufura vaera - gumbo (totem - leg) and the Mbire vaera -_shoko (monkey) under chiefs Ndanga and Nyakunuhwa respectively in Zaka d is tric t, and the Ndau vaera - moyo (heart) under chief Gudo in Chiredzi district. -

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No. of Stations BULAWAYO METROPOLITAN PROVINCE 1 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 City Hall 1608 2 2 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Eveline High School 561 1 3 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Mckeurtan Primary School 184 1 4 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Milton Junior School 294 1 5 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Old Bulawayo Polytechnic 259 1 6 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Peter Pan Nursery School 319 1 7 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Pick and Pay Tent 473 1 8 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Robert Tredgold Primary School 211 1 9 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Airport Primary School 261 1 10 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Aiselby Primary School 118 1 11 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Infants School 435 1 12 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Junior School 1256 2 13 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Falls Garage Tent 273 1 14 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo -

Harurwa (Edible Stinkbugs) and Conservation in South-Eastern Zimbabwe

FOREST INSECTS, PERSONHOOD AND THE ENVIRONMENT: HARURWA (EDIBLE STINKBUGS) AND CONSERVATION IN SOUTH-EASTERN ZIMBABWE MUNYARADZI MAWERE (MWRMUN001) Thesis Submitted For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Department of Social Anthropology, School of African and Gender Studies, Anthropology and Linguistics University of Cape Town August 2014 University of Cape Town Supervisors: A/PROF. LESLEY GREEN DR. FRANK MATOSE The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Signature……………………………………………………………………………………….. Date……………………………………………………………………………………………. i Acknowledgements My fieldwork in the Norumedzo and the writing of this thesis involved the help of many people. Prior to my field research, my training at the University of Cape Town was shaped under the guidance of A/Prof. Lesley Green, Prof. Francis B. Nyamnjoh, Prof Fiona Ross, Prof. Jean Pierre Warnier and Prof. Akhil Gupta. The latter two were Visiting Professors in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cape Town in 2011. -

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No

PROVISIONAL VOTERS' ROLL INSPECTION CENTRES Ser Province District Constituency Local Authority Ward Polling Station Name Registrants No. of Stations BULAWAYO METROPOLITAN PROVINCE 1 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 City Hall 1608 2 2 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Eveline High School 561 1 3 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Mckeurtan Primary School 184 1 4 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Milton Junior School 294 1 5 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Old Bulawayo Polytechnic 259 1 6 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Peter Pan Nursery School 319 1 7 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Pick and Pay Tent 473 1 8 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 1 Robert Tredgold Primary School 211 1 9 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Airport Primary School 261 1 10 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Aiselby Primary School 118 1 11 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Infants School 435 1 12 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Baines Junior School 1256 2 13 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo Municipality 2 Falls Garage Tent 273 1 14 Bulawayo Metropolitan Bulawayo Bulawayo Central Bulawayo -

Masvingo Province

Page 1 of 42 Masvingo Province LOCAL AUTHORITYASSEMBLY WARD NUMBER NAME OF POLLING STATION FACILITY Bikita RDC Bikita East 14 Negovanhu Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 14 Marirangwe Secondary school Bikita RDC Bikita East 14 Makamba Training Centre Hall Bikita RDC Bikita East 14 Negovano/Diyo BC Tent 4 Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Mbirashava Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Magurwe Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Museti Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Nerumedzo Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Mudzami Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Silveira Secondary school Bikita RDC Bikita East 15 Chivaka Primary School 7 Bikita RDC Bikita East 16 Beta Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 16 Chinyamapere Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 16 Chikwira Secondary school Bikita RDC Bikita East 16 Chigumisirwa Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 16 Chigumisirwa Business Centre 5 Bikita RDC Bikita East 17 Boora Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 17 Nerunhengu Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 17 Boora BC Tent Bikita RDC Bikita East 17 Mushambanevhu BC Tent Bikita RDC Bikita East 17 Masekayi Secondary school 5 Bikita RDC Bikita East 18 Chikuku Health centre Bikita RDC Bikita East 18 Mamutse Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 18 Mutsinzwa PS Primary School 3 Bikita RDC Bikita East 20 Chirorwe Health centre Bikita RDC Bikita East 20 Musukutwa Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 20 Chirorwe Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 20 Negwari Primary School Bikita RDC Bikita East 20 Nebwari Primary -

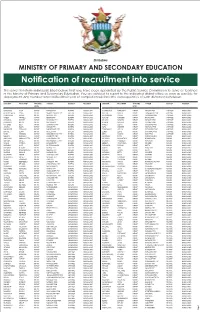

Notification of Recruitment Into Service

Zimbabwe Notification of recruitment into service This serves to inform individuals listed below, that you have been appointed by the Public Service Commission to serve as teachers in the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. You are advised to report to the indicated district office as soon as possible for deployment. Any member who falsified their year of completion will face the consequences of such dishonest behaviour. -

Harnessing of Social Capital As a Determinant for Climate Change Adaptation in Mazungunye Communal Lands in Bikita, Zimbabwe

Hindawi Scientifica Volume 2021, Article ID 8416410, 9 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8416410 Research Article Harnessing of Social Capital as a Determinant for Climate Change Adaptation in Mazungunye Communal Lands in Bikita, Zimbabwe Louis Nyahunda and Happy Mathew Tirivangasi Department of Research Administration and Development, University of Limpopo, P.bag X1106, Mankweng 0727, South Africa Correspondence should be addressed to Happy Mathew Tirivangasi; [email protected] Received 28 May 2020; Revised 3 November 2020; Accepted 9 April 2021; Published 19 April 2021 Academic Editor: Hans Sanderson Copyright © 2021 Louis Nyahunda and Happy Mathew Tirivangasi. +is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. +e livelihoods of rural people have been plagued by the precarious impacts of climate change–related disasters manifesting through floods, heat waves, droughts, cyclones, and erratic temperatures. However, they have not remained passive victims to these impacts. In light of this, rural people are on record of employing a plethora of adaptation strategies to cushion their livelihoods from climate change impacts. In this vew, the role of social capital as a determinant of climate change adaptation is underexplored. Little attention has been paid to how social capital fostered through trust and cooperation amongst rural households and communities is essential for climate change adaptation. +is study explored how people in Mazungunye communal lands are embracing social capital to adapt to climate change impacts. +e researchers adopted a qualitative research approach guided by the descriptive research design. -

Parliamentary Elections 2005 Polling Stations Masvingo

PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2005 POLLING STATIONS MASVINGO PROVINCE As published in The Zimbabwe Independent dated March 18, 2005 Polling stations shall be open from 0700 hours to 1900 hours on polling day BIKITA EAST CONSTITUENCY No Polling station Presiding Officer 1 Angus Ranch Primary School Maradza Averlet 2 Bambaninga Primary School Mupfavi Antony 3 Betha Primary School Paradzai Engelbert 4 Boora Primary School Murigo Godfrey 5 Chada Primary School Tamuka Abel 7 Checheni Prinary School Kanjanga Esther D 8 Chedutu Primary School Ziki Christina 9 Chibvuure Primary School Shumba Taitivanhu 10 Chigumisirwa Primary School Rukono Maxwell 11 Chigwite Primary School Makaradza Philemon 12 Chikuku Primary School Mangezi Simbarashe 13 Chinyamapere Primary School Musikavanhu Wilson 14 Chinyika Primary School Mapolisa Taurai 15 Chiremwaremwa Primary School Muresherwa Edson 16 Chisungo Primary School Madzivadondo Edward 17 Chitenderano Primary School Hunde John 18 Chitsanga Primary School Jange Porina 19 Gawa Primary School Makumbo Effeso 20 Gomba Primary School Chigidhani Gabriel 21 Hammond Ranch Offices Mukuwe Ivy 22 Humani Ranch Primary School Garanowako Chrles 23 Kudadisa Secondary School Jange Gladys 24 Machikode Business Centre Mhere Edmore 25 Madzivire Primary School 26 Mafaune Primary School 27 Magocha Primary School 28 Makondo Primary School 29 Mamutse Primary School 30 Mandadzaka Primary School 31 Masapasi Workshop 32 Mashoko Mission 33 Matendere Ranch 34 Mbuyanehanda Primary School 35 Msaizi Ranch 36 Mujiji Primary School 37 Mukanga Primary -

October 2015

OCTOBER 2015 i Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG) is a non-governmental organization working to improve natural resources governance in Zimbabwe. Communities, Companies and Conflict, Centre for Natural Resource Governance, Zimbabwe 2015 Centre for Natural Resource Governance 90 Fourth Street, ZimRights House, Alveston Court, Between 4th Street and Baines Avenue, Harare, Zimbabwe. ii Centre For Natural Resource Governance is grateful to The Heinrich Boll Foundation For their generous support towards this project iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 1 Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and Background........................................................................................................ 4 Research problem and rationale ............................................................................................... 6 Objectives of the study ............................................................................................................. 8 Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 8 Research questions ................................................................................................................... 8 research process ......................................................................................................................