After the Fire: Reconstruction Following Destructive Fires in Historic Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Restoration 2004

Introduction Restoration A major new campaign for Britain’s historic buildings at risk launching in May across the UK Restoration returns in 2004 to throw a lifeline to Jane Root, Controller of BBC Two, says:“Last one of Britain’s endangered historic buildings. year Restoration really captured the imagination of the public and stood out as a shining Viewers again hold the fate of a building in example of how great ideas like this can their hands as they choose among 21 of the become so much more than just a TV UK’s threatened architectural gems. programme. Restoration will build on this success, offering viewers another chance to On Saturday 8 May on BBC Two, Griff Rhys rescue an important part of Britain’s heritage Jones presents a launch programme for the and to get involved in saving buildings in their 2004 Restoration campaign.This kicks off fund- local area.” raising events and local campaigns across the UK, leading up to the transmission of the Nikki Cheetham, Managing Director of series in the summer. Endemol UK Productions, adds:“Last year Restoration viewers proved that they cared This year viewers are being encouraged to get passionately about Britain’s threatened historic even more involved in the campaign.A free buildings.This year they’ll have another chance Restoration campaign pack called So You Want To to make a real difference – they can actually Save An Historic Building is available by calling help save buildings as diverse as a castle, a 08700 100 150 or through the website at workhouse, a concrete house and a jail.” www.bbc.co.uk/restoration Seven one-hour programmes are devoted to a Additional programming will be broadcast on geographical area of the UK and focus on BBC Four, and local BBC television and radio three properties at risk, revealing the programmes across the UK will keep viewers crumbling architectural treasures we could bang up to date with the latest news on the lose for ever. -

Proceedings and Notes – No. 34 – January 2020

The Art Workers’ Guild Proceedings and Notes – No. 34 – January 2020 Katharine Coleman – City of London. Image © Ester Segarra. A MESSAGE FROM THE MASTER Indeed, there are many people to thank for helping intrepidly sought out the delights of Scotland, including Aged 16, Anne was enjoying scenery-making for to run such an enjoyable year: the Scottish parliament, the new V&A in Dundee and school plays, and designing an enormous lobster Being Master has been enormous fun and I am • The Master’s suppers and the lunch for Past, Present weaving at the Dovecot Studios. Art Worker Angie float for the Lord Mayor’s Show. School results were grateful to everyone in the Guild for this experience. and Future Masters were all beautifully catered Lewin opened her studio and generously showed us below expectations due to the discovery of parties and Organising the talks was daunting, but the enthusiasm for, including illustrated menus by Art Worker her techniques in printmaking and watercolour. In bunking off. This meant not being able to take up a and willingness of speakers to talk at the Guild are a Jane Dorner. The third dinner coincided with the the Borders, we visited the immaculately restored place studying art history. After a few months in France testament to the respect in which it is held. Some of the speaker Clary Salandy’s birthday, rounding off an 18th-century Marchmont House, with two Arts and as a teacher’s assistant, she moved on. She secured a best talks were by Art Workers themselves, and it was extraordinary talk describing the structure, history Crafts wings designed by Sir Robert Lorimer and a job as a receptionist in a hotel in Florence where they wonderful to hear the many ways in which the Guild’s and making, as well as the meaning behind Carnival wonderful collection of rush-seated chairs and Arts and had once stayed, but after a few months she moved on expertise, innovation and material know-how nurtures and the making of its costumes. -

Stevens Competition 2019 Launched

the WORSHIPFUL COMPANY of GLAZIER S & PAINTERS OF GLASS Issue Number 56 Autumn 2 01 8 Stevens Competition 2019 launched MICHAEL HOLMAN writes: The task facing entrants to the 2019 Stevens Competition for Architectural Glass is to design a panel to be installed in the reception area of the Proton Beam Therapy Unit (PBT) currently under construction at University College Hospital, London. The PBT is a new clinical facility using a high-energy beam of particles to destroy cancer cells and is due to be commissioned in 2020. Many NHS hospitals now recognise that the provision of the arts within their An artist’s impression of the Proton Beam Therapy Unit currently under construction at University Hospital. environment is integral to patient wellbeing and this will be the fourth occasion on which and the Macmillan Cancer Centre. not required to prepare the stained glass University College Hospital has been the This year, for the first time, an additional sample which is an integral feature of the location for the Stevens Competition. competition is being sponsored by the Stevens Competition. Previous examples of panels are to be found Reflections of The Lord Mayor charity for the The brief giving full details of the in the Radiotherapy Department, the design of a panel by those in the age group competition is to be found on the Company’s Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Antenatal Clinic 16–24 years. In this instance competitors are website. I 1943 and 6 11 Squadron sets off over Biggin Hill – and 75 years later it begins a link with the Glaziers’ Company at the personal initiative of Master Keith Barley. -

Secret Address Book

COUNTRY LIFE’S secret address book You’ve just bought a country house and now you’re faced with the business of restoring and enhancing it—and possibly knocking it down and starting all over again. Or perhaps you’ve decided that the house you’re in isn’t fulfilling its potential. Who are you going to call? COUNTRY LIFE gives you the top 100 architects, interior designers, builders and garden designers who have the knowledge and experience to create the rural retreat of your dreams Compiled by Arabella Youens T is rare that a house is ever frozen in time. Successive owners have needs and tastes that add something new; colour palettes change, layouts are Ireconfigured, cellars become media rooms, derelict outbuildings are reborn as swim- ming pools. Or sometimes they simply need to be protected from the ravages of time— or the ravages of their previous owners. All these changes offer an exciting opp- ortunity to make a house your own. We are fortunate in this country to have a wealth of experts to help us on our way—archi- tects, designers and builders whose intimate knowledge of country houses and their gar- dens offer an extraordinary opportunity to maximise the possibilities that they pre- sent, whether they are village houses, con- verted barns or listed manor houses. The following are those who COUNTRY LIFE considers to have the experience, knowl- Quinlan & Francis Terry Architects replaced a Victorian extension with something more edge and skill—and a little magic—required in keeping with the period for Higham House in Essex to take a country house to the next exciting stage in its evolution. -

Westminster Abbey 2016 Report to the Visitor Her Majesty the Queen 4 — 11 Contents the Dean of Westminster the Very Reverend Dr John Hall

Westminster Abbey 2016 Report To The Visitor Her Majesty The Queen 4 — 11 Contents The Dean of Westminster The Very Reverend Dr John Hall 12 — 15 The Sub-Dean, Archdeacon of Westminster and Canon Theologian The Reverend Professor Vernon White 16 — 19 The Canon Treasurer and Almoner The Reverend David Stanton 20 — 23 The Rector of St Margaret’s and Canon of Westminster The Reverend Jane Sinclair 26 — 29 The Canon Steward The Reverend Anthony Ball 30 — 33 The Receiver General and Chapter Clerk Sir Stephen Lamport KCVO DL 39 — 43 Summarised Financial Statement 44 — 47 Abbey People (Front Cover) Her Majesty The Queen receives an early birthday present from the choristers of Westminster Abbey after the annual Commonwealth Day service in March: a framed picture of ‘Choir Boy’ – the Queen’s first winner, which won the Royal Hunt Cup at Ascot on 17th June 1953. 1 2016 Report Westminster Abbey The Dean of Westminster The Dean of Westminster Last summer the Sub-Dean, Archdeacon and Rector of St Margaret’s, Canon Andrew Your Majesty, Tremlett, took up Your Majesty’s appointment as Dean of Durham. Canon Vernon White became Sub-Dean and Archdeacon of Westminster in addition to his role as Canon Theologian and Canon Jane Sinclair, previously Canon Steward, succeeded Canon Tremlett as Rector The Dean and Chapter of Westminster takes great pleasure in offering Your Majesty as the of St Margaret’s. Canon Anthony Ball took up the position of Canon Steward in September. Abbey’s Visitor our annual report on the fulfilment of the mission of the Collegiate Church of St Peter in Westminster during the Year of Our Lord 2016. -

Westminster Abbey 2019 Report to the Visitor Her Majesty the Queen 2 — 5 Contents the Dean of Westminster the Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle

Westminster Abbey 2019 Report To The Visitor Her Majesty The Queen 2 — 5 Contents The Dean of Westminster The Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle 6 — 11 Serving almighty God and the Sovereign 12 — 17 Serving the nation 18 — 23 Serving pilgrims and visitors 24 — 29 Care of the fabric and the Abbey collection 30 — 35 Management of the Abbey 36 — 41 Financial performance and risk 45 — 49 Summarised Financial Statement 50 — 59 Abbey People (Front Cover) As they left the Abbey’s service to mark the 750th anniversary of Henry III’s church, Her Majesty The Queen and Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall received posies from Theo and Margaret, children of the Abbey’s Keeper of the Muniments, Dr Matthew Payne. 1 2019 Report Westminster Abbey The Dean of Westminster The Dean of Westminster Dean Bradley’s tomb, at our feet as we gather for Evensong, includes words of scripture. Your Majesty, ‘I have loved the habitation of thy house,’ it says. I can look at that night by night and be reminded that, amidst the opportunities and responsibilities that the Abbey brings, here was another Dean who was simply glad to be in such a glorious building and in such very good company. As the day draws to a close, the Abbey clergy and choir assemble in a corner of the nave for a prayer before we process into Evensong. Immediately, we cross the grave of George These words, and the rest of this Annual Report, were written before the arrival of Granville Bradley, who retired as Dean of Westminster in 1902 just after the coronation Covid-19, which is testing our resilience and resourcefulness in ways which were of Your Majesty’s great-grandfather, King Edward VII. -

Westminster Abbey 2018 Report to the Visitor Her Majesty the Queen 2 — 11 Contents the Dean of Westminster the Very Reverend Dr John Hall

Westminster Abbey 2018 Report To The Visitor Her Majesty The Queen 2 — 11 Contents The Dean of Westminster The Very Reverend Dr John Hall 12 — 17 The Sub-Dean, Archdeacon of Westminster and Canon Treasurer The Venerable David Stanton 18 — 23 The Rector of St Margaret’s and Canon of Westminster The Reverend Jane Sinclair 24 — 29 The Canon Steward and Almoner The Reverend Anthony Ball 30 — 35 The Canon Theologian The Reverend Dr James Hawkey 36 — 41 The Receiver General, Chapter Clerk and Registrar Paul Baumann CBE 45 — 49 Summarised Financial Statement 52 — 55 Abbey People (Front Cover) Her Majesty The Queen greets Patrick from the Abbey Choir after the annual Commonwealth Service in March. 1 2018 Report Westminster Abbey The Dean of Westminster The Dean of Westminster Another major theme of the Abbey’s life is in relation to ecumenical and inter-faith Your Majesty, relations. The Commonwealth Service marks one of the occasions in the year when we welcome representatives of the wider faith communities to participate within the service with prayers from their own faith traditions. We see this as a duty of the Abbey, representing as it does Faith at the Heart of the Nation, and with a commitment therefore In October 2019, we shall celebrate the 750th anniversary of the dedication of the current to bring together into the precious space we occupy representatives of all people of faith. Abbey church. This, the third Abbey church building, was consecrated on 13th October It is a privilege and pleasure to see Muslim, Jewish and Christian faith leaders, as well 1269. -

The Country Life Top 100 Britain Is Blessed with Some of the World’S Greatest Architects, Interior Designers, Garden Designers and Specialist Craftspeople

The COUNTRY LIFE Top 100 Britain is blessed with some of the world’s greatest architects, interior designers, garden designers and specialist craftspeople. For the fourth year running, COUNTRY LIFE selects those with a demonstrable track record in creating the perfect country home an architectural and masterplanning practice Craig Hamilton Architects Architects and, with Bridie Hall, the cornucopia of decor- A clear focus on Classical architecture has ADAM Architecture ative delights that is the Pentreath & Hall earned this Radnorshire-based practice Highly respected experts in traditional archi- shop. Recent projects include the interior plenty of plaudits. The company special- tecture and renowned for significant new restoration of the early-18th-century Chettle ises in the design of new country houses, country houses, refurbishments and con- House in Dorset and the interior design including one for The Prince of Wales in sidered alterations to listed properties, this of the former Hardy Amies townhouse on Carmarthenshire, as well as sacred and practice is working on the extension of a listed Savile Row, W1, as a flagship store for the monumental architecture. house on a country estate in Berkshire and tailoring services of Hackett. 01982 553312; a new country villa in Hampshire. 020–7430 2424; www.benpentreath.com www.craighamiltonarchitects.com 01962 843843; www.adamarchitecture.com Benjamin Tindall Architects Donald Insall Associates With more than 40 years’ experience, Ben- This leading architectural practice, now 62 ANTA Architecture jamin Tindall continues to run his Edinburgh years old with eight UK offices, specialises Conservation architect Lachlan Stewart practice today. Renowned for repairs and in the care, repair and adaptation of his- leads a practice known for both new houses alterations to historic buildings, the firm offers toric buildings and the design of new ones, designed in the Scottish vernacular and for a full range of services, from landscaping including private houses, on sensitive sites. -

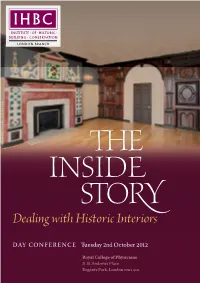

Dealing with Historic Interiors

© London Borough of Enfield Photo tHe insiDe STory Dealing with Historic Interiors DAY CONFERENCE Tuesday 2nd October 2012 Royal College of Physicians 11 St Andrews Place Regent’s Park, London NW1 4LE tHe Inside STory Dealing with Historıc Interiors Our listed buildings are facing an unprecedented amount of pressure for change. New uses, changes in lifestyle and responses to climate change can all pose a serious threat to the often fragile interiors of these heritage assets. Against a background of new government priorities and guidance, how should heritage professionals deal with these pressures? We need to provide buildings with a sustainable future without compromising their significance. Are we getting the balance right? In this, the seventh of our IHBC London conferences our speakers, who reflect a diversity of professional backgrounds and organisations, will consider these issues by drawing on their experience of buildings ranging from high profile public projects to more modest residential dwellings. As is the case with all historic buildings, it is never ‘one size fits all’ and the conference will look at how, with the right degree of imagination and compromise, a range of innovative solutions can be achieved. A number of case studies will illustrate not only the general principles raised, but also problem-solving in detail. The conference will be of relevance to conservation officers and other heritage professionals, architects, architectural historians, planners, engineers, surveyors and archaeologists. This one-day conference is to be held in Denys Lasdun’s Grade I listed Royal College of Physicians (1960–64); an award-winning conference venue. VENUE The Royal College of Physicians is located at 11 St Andrews Place, Regent’s Park and can be reached: By National Rail from Euston, Kings Cross, Marylebone and Paddington stations By Tube from Regent’s Park (Bakerloo Line), Great Portland Street (Circle, Metropolitan, Hammersmith and City lines), Warren Street (Victoria and Northern lines) By Bus from Paddington and Marylebone, Nos. -

SAVE Newsletter Spring Summer 2017

NEWSLETTER SPRING–SUMMER 2017 CASEWORK BUILDINGS AT RISK PUBLICATIONS EVENTS SAVE TRUST SAVE EUROPE’S HERITAGE NEWSLETTER SPRING–SUMMER 2017 CASEWORK PUBLICATIONS BUILDINGS AT RISK BOOK REVIEWS EVENTS SUPPORT SAVE SAVE is a strong independent voice in conservation, free Legacies: to respond rapidly to emergencies and to speak out loud Remembering SAVE in your will can be an eff ective way for the historic environment. Since 1975 SAVE has been to ensure that endangered historic buildings are given a campaigning for threatened historic buildings and second chance, and become a place of enjoyment for sustainable reuses. Our message is one of hope: that great future generations. By including a gift to SAVE, large or buildings can live again. small, you can help to ensure that your legacy lives on in SAVE does not receive public funding from the the very fabric of British architecture. government, meaning that we are reliant on the Please don’t forget to include our charity number (269129) generosity of our Friends, Saviours and members of the when writing your will, and seek professional advice. public, so please consider supporting us. Friends: Fighting Fund: Join a lively group of like-minded people and keep up to SAVE is only able to fi ght campaigns against demolition date with all the latest campaigns for just £36 a year. and harmful development by building a specialist team for each project with legal, fi nancial and architectural The benefi ts of becoming a Friend include: expertise. The direct costs of bringing such teams • A complimentary publication when joining together are covered by the Fighting Fund. -

Final Restoration 2004

RESTORATION Griff Rhys Jones kicks off a major new campaign for Britain’s historic buildings at risk Launching in May 2004 across the UK Contents Restoration Introduction . 2 Notes to Editors . 4 Interview: Griff Rhys Jones on Restoration . 5 Biographies of buildings and contacts . 9 Biographies of presenters and experts . 24 BBC Scotland – Factual programmes . .27 Endemol UK Productions . 28 Publicity contacts across the UK . 29 Restoration Introduction Restoration A major new campaign for Britain’s historic buildings at risk launching in May across the UK Restoration returns in 2004 to throw a lifeline to Jane Root, Controller of BBC Two, says:“Last one of Britain’s endangered historic buildings. year Restoration really captured the imagination of the public and stood out as a shining Viewers again hold the fate of a building in example of how great ideas like this can their hands as they choose among 21 of the become so much more than just a TV UK’s threatened architectural gems. programme. Restoration will build on this success, offering viewers another chance to On Saturday 8 May on BBC Two, Griff Rhys rescue an important part of Britain’s heritage Jones presents a launch programme for the and to get involved in saving buildings in their 2004 Restoration campaign.This kicks off fund- local area.” raising events and local campaigns across the UK, leading up to the transmission of the Nikki Cheetham, Managing Director of series in the summer. Endemol UK Productions, adds:“Last year Restoration viewers proved that they cared This year -

Restoration Pack

Contents Restoration Interview with Griff Rhys Jones . 6 Biographies of buildings and their celebrity advocates . 9 Restoration Secrets on BBC Four . 28 Heritage facts and figures . 29 Biographies of presenters and experts . 30 BBC Scotland - Factual Programmes . 33 Endemol UK Production . 34 Restoration Griff Rhys Jones’s view Restoration Man Griff Rhys Jones talks about Restoration important that they were represented by reputable groups of supporters, comprised of experts and volunteers. Part of my job was to interview them and check them out. I became a sort of an impromptu planning officer on the viewers behalf, the practicalities of the buildings and their supporters who were seeking what is after all public money.We’re not going to give it away without a struggle. These buildings were chosen with great care. Sometimes I went along thinking; well I’m not sure on paper that this building is up to scratch. But I can honestly tell you, quite sincerely, that I never failed to be fascinated by any of the places. From Kinloch Castle, a complete Edwardian Scottish holiday island fantasy, with the ashtray still on the piano and During the course of each programme we the leopardskin rugs on the floor as if the feature three separate buildings at risk.We owner is going to walk in and plump himself tell their stories and try to present some down on the kilim-covered sofa any moment, sense of their historical background by where we spoke in whispers... meeting people who are associated and telling the buildings’ histories. ...to the shabby grandeur of the Cathedral of the potteries, the extraordinary Bethesda Marianne Suhr and Ptolemy Dean, both Chapel in Stoke, a moving, spectacular, intricate qualified restoration architects, go in with no interior which as recently as 20 years ago was prior knowledge of what they are about to see, full of a hot, gospelling congregation ..