Study Guide for the CRYPTOGRAM by David Mamet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's 'Forgotten' Contribution to the History of the Prime-Time BBC1 Contemporary Single TV Play Slot Cook, John R

'A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime-time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot Cook, John R. Published in: Visual Culture in Britain DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Author accepted manuscript Link to publication in ResearchOnline Citation for published version (Harvard): Cook, JR 2018, ''A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime- time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot', Visual Culture in Britain, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please view our takedown policy at https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179 for details of how to contact us. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 1 Cover page Prof. John R. Cook Professor of Media Department of Social Sciences, Media and Journalism Glasgow Caledonian University 70 Cowcaddens Road Glasgow Scotland, United Kingdom G4 0BA Tel.: (00 44) 141 331 3845 Email: [email protected] Biographical note John R. Cook is Professor of Media at Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland. He has researched and published extensively in the field of British television drama with specialisms in the works of Dennis Potter, Peter Watkins, British TV science fiction and The Wednesday Play. -

Edmond Press

International Press International Sales Venice: wild bunch The PR Contact Ltd. Venice Phil Symes - Mobile: 347 643 1171 Vincent Maraval Ronaldo Mourao - Mobile: 347 643 0966 Tel: +336 11 91 23 93 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Carole Baraton 62nd Mostra Venice Film Festival: Tel: +336 20 36 77 72 Hotel Villa Pannonia Email: [email protected] Via Doge D. Michiel 48 Gaël Nouaile 30126 Venezia Lido Tel: +336 21 23 04 72 Tel: 041 5260162 Email: [email protected] Fax: 041 5265277 Silva Simonutti London: Tel: +33 6 82 13 18 84 The PR Contact Ltd. Email: [email protected] 32 Newman Street London, W1T 1PU Paris: Tel: + 44 (0) 207 323 1200 Wild Bunch Fax: + 44 (0) 207 323 1070 99, rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris Email: [email protected] tel: + 33 1 53 01 50 20 fax: +33 1 53 01 50 49 www.wildbunch.biz French Press: French Distribution : Pan Européenne / Wild Bunch Michel Burstein / Bossa Nova Tel: +33 1 43 26 26 26 Fax: +33 1 43 26 26 36 High resolution images are available to download from 32 bd st germain - 75005 Paris the press section at www.wildbunch.biz [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info Synopsis Cast and Crew “You are not where you belong.” Edmond: William H. Macy Thus begins a brutal descent into a contemporary urban hell Glenna: Julia Stiles in David Mamet's savage black comedy, when his encounter B-Girl: Denise Richards with a fortune-teller leads businessman Edmond (William H. -

Education at the Races

News GLOBE TO OPEN SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE NICHOLAS HYTNER WITH NON-SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCES TO LEAVE NATIONAL Curriculum THEATRE IN 2015 focus with Patrice Baldwin Sir Nicholas Hytner is to step down as artistic director at the National Theatre after more than a decade at the helm. Announcing his Education at ‘the races’ departure, Hytner said: ‘It’s been a joy and a privilege to lead the At the education race course, tension is mounting. The subject horses National Theatre for ten years and I’m looking forward to the next two. that have been allowed to compete will all be running very soon. Some ‘I have the most exciting and most fulfilling job in the English- have the usual head start, some are kept lame and may not be allowed speaking theatre; and after 12 years it will be time to give someone to enter the main race at all. What happens behind the scenes in various else a turn to enjoy the company of my stupendous colleagues, who stables is already determining the subject and GCSE winners, and the together make the National what it is.’ odds are low on drama being allowed to compete fairly in the race. Hytner came to the National Theatre as the successor of Sir Trevor Drama continues to be held back. Michael Gove is apparently Nunn in 2003. He has since headed up some of the National’s most avoiding having to get an act of parliament passed, which is needed commercially successful work to date, including The History Boys, were he to change the basic structure of the current national curriculum One Man, Two Guvnors and War Horse. -

David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521894689 - The Cambridge Companion to David Mamet - Edited by Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More information 1 CHRISTOPHER BIGSBY David Mamet In 1974, a play set in part in a singles bar, laced with obscene language and charged with a seemingly frenetic energy, was voted Best Chicago Play. Transferred to Off Off and Off Broadway it picked up an Obie Award. Sexual Perversity in Chicago was not David Mamet’s first play, but it did mark the beginning of a career that would astonish in both its range and depth. The following year American Buffalo opened at Chicago’s Goodman The- atre in an “alternative season.” It was well received and opened on Broadway fifteen months later where it won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. It ran for 135 performances, hardly a failure but in the hit or miss world of New York, not a copper-bottomed success either. Nonetheless, in three years he had announced his arrival in unequivocal terms. David Mamet came as something of a shock, not least because his first public success, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, seemed brutally direct in terms of its language and subject, as did American Buffalo. But it was already clear to many that here was a distinctive talent, albeit one that some critics found difficult to assess, not least because of his characters’ scatological language and fractured syntax, along with the apparent absence, in his plays, of a conventional plot. They praised what they took to be his linguistic naturalism, as though his intent had been to offer an insight into the cultural lower depths while capturing the precise rhythms of contemporary speech (though he did invoke Gorky’s The Lower Depths as being, like a number of his own plays, a study in stasis). -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

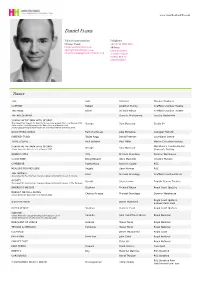

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442

English 252: Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442-07-387-1551 61/63 Cartwright Gardens London, UK WC1H 9EL [*Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 28 *1:00 p.m. Beauties and Beasts. Retold by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate). Adapted by Tim Supple. Dir Melly Still. Design by Melly Still and Anna Fleischle. Lighting by Chris Davey. Composer and Music Director, Chris Davey. Sound design by Matt McKenzie. Cast: Justin Avoth, Michelle Bonnard, Jake Harders, Rhiannon Harper- Rafferty, Jack Tarlton, Jason Thorpe, Kelly Williams. Hampstead Theatre *7.30 p.m. Little Women: The Musical (2005). Dir. Nicola Samer. Musical Director Sarah Latto. Produced by Samuel Julyan. Book by Peter Layton. Music and Lyrics by Lionel Siegal. Design: Natalie Moggridge. Lighting: Mark Summers. Choreography Abigail Rosser. Music Arranger: Steve Edis. Dialect Coach: Maeve Diamond. Costume supervisor: Tori Jennings. Based on the book by Louisa May Alcott (1868). Cast: Charlotte Newton John (Jo March), Nicola Delaney (Marmee, Mrs. March), Claire Chambers (Meg), Laura Hope London (Beth), Caroline Rodgers (Amy), Anton Tweedale (Laurie [Teddy] Laurence), Liam Redican (Professor Bhaer), Glenn Lloyd (Seamus & Publisher’s Assistant), Jane Quinn (Miss Crocker), Myra Sands (Aunt March), Tom Feary-Campbell (John Brooke & Publisher). The Lost Theatre (Wandsworth, South London) Thursday December 29 *3:00 p.m. Ariel Dorfman. Death and the Maiden (1990). Dir. Peter McKintosh. Produced by Creative Management & Lyndi Adler. Cast: Thandie Newton (Paulina Salas), Tom Goodman-Hill (her husband Geraldo), Anthony Calf (the doctor who tortured her). [Dorfman is a Chilean playwright who writes about torture under General Pinochet and its aftermath. -

David Mamet in Conversation

David Mamet in Conversation David Mamet in Conversation Leslie Kane, Editor Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2001 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ∞ Printed on acid-free paper 2004 2003 2002 2001 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data David Mamet in conversation / Leslie Kane, editor. p. cm. — (Theater—theory/text/performance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-09764-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-472-06764-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mamet, David—Interviews. 2. Dramatists, American—20th century—Interviews. 3. Playwriting. I. Kane, Leslie, 1945– II. Series. PS3563.A4345 Z657 2001 812'.54—dc21 [B] 2001027531 Contents Chronology ix Introduction 1 David Mamet: Remember That Name 9 Ross Wetzsteon Solace of a Playwright’s Ideals 16 Mark Zweigler Buffalo on Broadway 22 Henry Hewes, David Mamet, John Simon, and Joe Beruh A Man of Few Words Moves On to Sentences 27 Ernest Leogrande I Just Kept Writing 31 Steven Dzielak The Postman’s Words 39 Dan Yakir Something Out of Nothing 46 Matthew C. Roudané A Matter of Perception 54 Hank Nuwer Celebrating the Capacity for Self-Knowledge 60 Henry I. Schvey Comics -

Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences

Shrews, Moneylenders, Soldiers, and Moors: Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Harelik, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Lesley Ferris, Adviser Professor Jennifer Schlueter Professor Shilarna Stokes Professor Robin Post Copyright by Elizabeth Harelik 2016 Abstract Shakespeare’s plays are often a staple of the secondary school curriculum, and, more and more, theatre artists and educators are introducing young people to his works through performance. While these performances offer an engaging way for students to access these complex texts, they also often bring up topics and themes that might be challenging to discuss with young people. To give just a few examples, The Taming of the Shrew contains blatant sexism and gender violence; The Merchant of Venice features a multitude of anti-Semitic slurs; Othello shows characters displaying overtly racist attitudes towards its title character; and Henry V has several scenes of wartime violence. These themes are important, timely, and crucial to discuss with young people, but how can directors, actors, and teachers use Shakespeare’s work as a springboard to begin these conversations? In this research project, I explore twenty-first century productions of the four plays mentioned above. All of the productions studied were done in the United States by professional or university companies, either for young audiences or with young people as performers. I look at the various ways that practitioners have adapted these plays, from abridgments that retain basic plot points but reduce running time, to versions incorporating significant audience participation, to reimaginings created by or with student performers. -

The York Realist

Press Release Tuesday 24 October 2017 DONMAR WAREHOUSE AND SHEFFIELD THEATRES ANNOUNCE FULL CASTING FOR THE YORK REALIST A Donmar Warehouse and Sheffield Theatres co-production By Peter Gill Donmar Warehouse: Thursday 8 February – Saturday 24 March 2018 PRESS NIGHT: Tuesday 13 February 2018 Sheffield Theatres: Tuesday 27 March – Saturday 7 April Director Robert Hastie Designer Peter McKintosh Lighting Designer Paul Pyant Sound Designer Emma Laxton Composer Richard Taylor Full cast includes Jonathan Bailey, Ben Batt, Lucy Black, Brian Fletcher, Lesley Nicol, Katie West and Matthew Wilson. The Donmar Warehouse and Sheffield Theatres today announce full casting for Donmar Associate Director and Sheffield Theatres Artistic Director Robert Hastie’s new revival of Peter Gill’s modern masterpiece The York Realist. Jonathan Bailey joins the cast as John, opposite the previously announced Ben Batt who will play George. Full casting also includes Lucy Black, Brian Fletcher, Lesley Nicol, Katie West and Matthew Wilson. ‘I live here. I live here. You can’t see that, though. You can’t see it. This is where I live. Here.’ A cottage, 1960s Yorkshire. The York Mystery plays are in rehearsal. Farmhand George strains against his roots as a new world opens up to him. Peter Gill’s influential play about two young men in love is a touching reflection on the rival forces of family, class and longing. Donmar Associate Robert Hastie returns for this timely revival from one of our greatest living playwrights, following his previous productions My Night with Reg and Splendour. Making theatre accessible to as many people as possible remains at the heart of the Donmar’s mission. -

SHIRCORE Jenny

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JENNY SHIRCORE - Make-Up and Hair Designer 2003 Women in Film Award for Best Technical Achievement Member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences THE DIG Director: Simon Stone. Producers: Murray Ferguson, Gabrielle Tana and Ellie Wood. Starring: Lily James, Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. BBC Films. BAFTA Nomination 2021 - Best Make-Up & Hair KINGSMAN: THE GREAT GAME Director: Matthew Vaughn. Producer: Matthew Vaughn. Starring: Ralph Fiennes and Tom Holland. Marv Films / Twentieth Century Fox. THE AERONAUTS Director: Tom Harper. Producers: Tom Harper, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Felicity Jones and Eddie Redmayne. Amazon Studios. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS Director: Josie Rourke. Producers: Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner and Debra Hayward. Starring: Margot Robbie, Saoirse Ronan and Joe Alwyn. Focus Features / Working Title Films. Academy Award Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hairstyling BAFTA Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hair THE NUTCRACKER & THE FOUR REALMS Director: Lasse Hallström. Producers: Mark Gordon, Larry J. Franco and Lindy Goldstein. Starring: Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren and Misty Copeland. The Walt Disney Studios / The Mark Gordon Company. WILL Director: Shekhar Kapur. Exec. Producers: Alison Owen and Debra Hayward. Starring: Laurie Davidson, Colm Meaney and Mattias Inwood. TNT / Ninth Floor UK Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JENNY SHIRCORE Contd … 2 BEAUTY & THE BEAST Director: Bill Condon. Producers: Don Hahn, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen. Disney / Mandeville Films.