Hindu Fasts and Feasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deepavali of the Gods

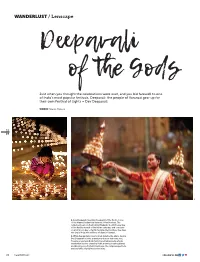

WANDERLUST / Lenscape Deepavali of the Gods Just when you thought the celebrations were over, and you bid farewell to one of India's most popular festivals, Deepavali; the people of Varanasi gear up for their own Festival of Lights – Dev Deepavali. WORDS Edwina D'souza 11 19 1 2 1. Dev Deepavali, meaning ‘Deepavali of the Gods’, is one of the biggest festivals in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. The festivities begin on Prabodhini Ekadashi, the 11th lunar day of the Kartika month of the Hindu calendar, and conclude on a full moon day – Kartik Purnima. During these five days, the city is lit up with millions of diyas (oil lamps). 2. While Ganga Aarti is performed daily by the ghats, during Dev Deepavali it is the grandest and most elaborate one. Twenty one priests hold multi-tiered lamps and perform rituals that involve chanting Vedic mantras, beating drums and blowing conch shells. Each year, the religious spectacle attracts lakhs of pilgrims and tourists. 74 FOLLOW US ON 11 19 Oil lamps are symbolic of Deepavali celebrations across India. During Dev Deepavali, courtyards, window panes, temples, streets and ghats in Varanasi are adorned with these oil lamps. Twinkling like stars under the night sky, these lit baskets create a captivating sight. 75 11 19 1 2 76 FOLLOW US ON 3 1. The city of Varanasi comes alive at the crack of dawn with devotees thronging the ghats and adjacent temples. An aerial view of the colourful rooftoops on the banks of the Ganges at sunrise; with Manikarnika Ghat in the foreground. -

2020 Religious Calendar

January 2020 Date Observance Monday 6th Putrada Ekadashi (starts from 4:38 p.m Sun 5th . ends 5:55 p.m. Mon 6th) Friday 10th Purnima (ends 2:22 p.m.) Monday 13th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Tuesday 14th Makar Sankranti/Pongal Monday 20th Shattila Ekadashi (starts 4:22 p.m. Sun. ends 3:37 p.m. Mon 20th ) Friday 24th Amavasya (ends 4:43 p.m.) Wednesday 29th Vasant Panchami/ Saraswati Jayanti February 2020 Date Observance Wednesday 5th Jaya Ekadashi (starts 11:21 a.m. Tues. ends 11:02 a.m. Wed. 5th ) Saturday 8th Purnima (ends 2:34 a.m. Sunday) Tuesday 11th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Tuesday 18th Vijaya Ekadashi (starts 4:04 a.m. Tues. ends 4:33 a.m. Wednesday) Friday 21st Maha Shiva Raatri Sunday 23rd Amavasya (ends 10:33 a.m.) March 2020 Date Observance Thursday 5th Amalaki Ekadashi (starts 2:50 a.m. Thu. ends 1:18 a.m Friday) Sunday 8th Holika Dahan Monday 9th Purnima/ Holi (ends 1:48 p.m.) note Holi is celebrated after Purnima ends Thursday 12th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Thursday 19th Paapmochinin Ekadashi (starts 6:57 p.m. Wed. ends 8:31 p.m. Thu.) Monday 23rd Amavasya (ends 5:29 a.m. Tuesday) Tuesday 24th Vasant NavRatri Begins April 2020 Date Observance Wednesday 1st Shri Durga Ashtami Thursday 2nd Shri Ram Navmi Saturday 4th Kamada Ekadashi (starts 3:29 p.m. Fri. ends 1:01 p.m. Sat.) Tuesday 7th Purnima/Shri Hanuman Jayanti (ends 10:36 p.m.) Friday 10th Shri Ganesh Chaturthi Saturday 18th Varuthini Ekadashi (starts 10:35 a.m. -

Satsang Sandesh

Satsang Sandesh India Temple Association, Inc. Hindu Temple, 25 E. Taunton Ave, Berlin, NJ 08009 SOUTH JERSEY ♦ DELAWARE ♦ PENNSYLVANIA (Non-Profit Tax Exempt Organization, Tax ID # 22-2192491) Vol. 58 No. 1 Phone: (855) MYMANDIR (855-696-2634) www.indiatemple.org JUNE 2015 Religious Calendar 30TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF June 7 Sunday PRAN-PRATISHTHA Graduation Day—Pooja in Mandir SAVE THESE DATES June 2 Tuesday SEPTEMBER 11, 12, 13, 2015 Vatapournima / Satyana- From the pages of history: Although ITA was formed in 1975, and a parcel of rayan Katha land was purchased in Lindenwold, it lacked the funds to construct a temple. It was June 12 Friday Lord Krishna’s divine grace that enabled our active members to merge and bring the Yogini Ekadashi assets of Shri Vallabhnidhi with ITA to purchase the existing property for our temple. June 17 Wednesday On May 6, 1982 we purchased the church property and the Hindu Mandir in Berlin Adhik Aashadh / Adhik became a reality, a place of worship for all Hindus in the Delaware Valley. Purushottam Mas Shri Narendra Amin was instrumental in providing the paintings for the temple beauti- June 28 Sunday fication as well as the meticulous details associated with the ordering of the idols from Kamala Ekadashi India. On May 31, 1985, the Idols of Radha-Krishna arrived at the Mandir. However, because of in-transit damage to Radhaji’s idol, the Pran-Pratishtha Mahotsava of Lord Monthly Activities Krishna was performed on September 20, 21 and 22, 1985. Over the past 30 years, the Kshama Raghuveer 707- temple and its services have grown along with the community. -

225 Poems from the Rig-Veda (Translated from Sanskrit And

Arts and Economics 225 Poems from the Rig-veda (Translated from Sanskrit and annotated by Paul Thieme) ["Gedichte aus dem Rig-Veda"] (Aus dem Sanskrit iibertragen und erHi.utert von Paul Thieme) 1964; 79 p. Nala and Damayanti. An Episode from the Mahabharata (Translated from Sanskrit and annotated by Albrecht Wezler) ["Nala und Damayanti. Eine Episode aus dem Mahabharata"] (Aus dem Sanskrit iibertragen und erHi.utert von Albrecht Wezler) 1965; 87 p. (UNESCO Sammlung reprasentativer Werke; Asiatische Reihe) Stuttgart: Verlag Philipp Reclam jun. These two small volumes are the first translations from Sanskrit in the "Unesco Collection of Representative Works; Asiatic Series", which the Reclam Verlag has to publish. The selection from the Rig-veda, made by one of the best European ~xperts, presents the abundantly annotated German translation of 'D~ Songs after a profound introduction on the origin and nature of the .Q.lg-veda. Wezler's Nala translation presents the famous episode in simple German prose, and is likewise provided with numerous explanatory notes. Professor Dr. Hermann Berger RIEM:SCHNEIDER, MARCARETE 'l'he World of the mttites (W.ith a Foreword by Helmuth Th. Bossert. Great Cultures of Anti ~~l~y, Vol. 1) [ ~le Welt der Hethiter"] ~M~t einem Vorwort von Helmuth Th. Bossert. GroBe Kulturen der ruhzeit, Band 1) ~~u8ttgart: J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung, 7th Edition 1965; 260 p., plates ~:e bOok un~er review has achieved seven editions in little more than th ~ears, a SIgn that it supplied a wide circle of readers not only with in: Information they need, but it has also been able to awaken lIit~~;st. -

List of Festival Celebrations at Durga Temple for the Year 2020

LIST OF FESTIVAL CELEBRATIONS AT DURGA TEMPLE FOR THE YEAR 2020 1. New Year Mata Jagran Wednesday, January 1st 2. Vaikunth Ekadeshi Puja Monday, January 6th 3. Lohri – Bonfire Celebration Monday, January 13th 4. Makar Sankranti Monday, January 14th 5. Vasant Panchami (Saraswati Puja) Wednesday, January 29th 6. Maha Shivaratri Utsav Friday, February 21st 7. Holika Dahan Monday, March 9th 8. Holi Mela To Be determined Tuesday, March 24th – 9. Vasant Navaratri Mahotsav Thursday, April 2nd 10. Durgashtami- Durga Hawan Wednesday, April 1st 11. Shri Ram Navami Thursday, April 2nd Shri Ramcharit Manas Akhand Paath 12. Saturday, April 4th Begins Shri Ramcharit Manas Akhand Paath 13. Sunday, April 5th Bhog Shri Hanuman Jayanti 14. Tuesday, April. 7th Samoohik Sundar Kand Paath 15. Baisakhi – Solar New Year Monday, April 13th 16. Akshaya Triteeya Saturday, April 25th 17. Guru Purnima Saturday, July 4th 18. Raksha Bandhan Monday, August 3rd 19. Shri Krishna Janmashtmi Tuesday, August 11th 20. Haritalika Teej Friday, August 21st Shri Ganesh Chaturthi 21. Saturday, August 22nd (Annual homam) 22. Labor Day – Annual Saraswati Puja Monday, September 7th Sharad Navaratri Utsav Saturday, October 17th – 23. Garba Dance (in hall downstairs) Saturday Oct 24th 24. Durga Ashtami Hawan Friday, October 23rd 25. Vijaya Dashami - Dussehra Sunday, October 25th 26. Dussehra Mela To be determined 27. Sharad Purnima Saturday, October 31st 28. Karva Chauth Puja Wednesday, November 4th 29. Dhan Teras Thursday, November 12th 30. Deepavali Saturday, November 14th 31. Annakoot (Goverdhan Puja) Sunday, November 15th 32. Tulsi Vivah Wednesday, November 25th Kartik Purnima - Kartik Deepam - 33. TBD Shata Rudrbhishak 34. Geeta Jayanti Friday, December 25th 35. -

Ramakatha Rasavahini II Chapter 14

Chapter 14. Ending the Play anaki was amazed at the sight of the monkeys and others, as well as the way in which they were decorated and Jdressed up. Just then, Valmiki the sage reached the place, evidently overcome with anxiety. He described to Sita all that had happened. He loosened the bonds on Hanuman, Jambavan, and others and cried, “Boys! What have you have done? You came here after felling Rama, Lakshmana, Bharatha, and Satrughna.” Sita was shocked. She said, “Alas, dear children! On account of you, the dynasty itself has been tarnished. Don’t delay further. Prepare for my immolation, so I may ascend it. I can’t live hereafter.” Sita pleaded for quick action. The sage Valmiki consoled her and imparted some courage. Then, he went with Kusa and Lava to the battle- field and was amazed at what he saw there. He recognised Rama’s chariot and the horses and, finding Rama, fell at his feet. Rama rose in a trice and sat up. Kusa and Lava were standing opposite to him. Valmiki addressed Rama. “Lord! My life has attained fulfilment. O, How blessed am I!” Then, he described how Lakshmana had left Sita alone in the forest and how Sita lived in his hermitage, where Kusa and Lava were born. He said, “Lord! Kusa and Lava are your sons. May the five elements be my witness, I declare that Kusa and Lava are your sons. Rama embraced the boys and stroked their heads. Through Rama’s grace, the fallen monkeys and warriors rose, alive. Lakshmana, Bharatha, and Satrughna caressed and fondled the boys. -

District Population Statistics, 22 Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh

.------·1 Census of India, 1951 I DISTRICT POPULATION STATISTICS UTTAR PRADESH 22-ALLAHABAD DISTRICT t I 315.42 ALLAHABAD: PluNnNG AND STATIONERY, UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA 1951 1953 ALL CPS Price, Re.1-S. FOREWORD THE Uttar Pradesh Government asked me in March, 1952, to supply them for the purposes of elections to local bodies population statistics with separation for scheduled castes (i) mohalla/ward -wise for urban areas, and (ii) village-wise for rural areas. The Census Tabulation Plan did not provide for sorting of scheduled castes population for areas smaller than a tehsil or urban tract and the request from the Uttar Pradesh Government came when the slip sorting had been finished and the Tabulation Offices closed. As the census slips are mixed up for the purposes of sorting in one lot for a tehsil or urban tract, collection of data regarding scheduled castes population by mohallas/wards and villages would have involved enormous labour and expense if sorting of the slips had been taken up afresh. Fortunately, however, a secondary census record, viz. the National Citizens' Register, in which each slip has been copied, was available. By singular foresight it had been pre pared mohalla/ward-wise for urban areas and village-wise for rural areas. The required information has, therefore, been extracted from this record. 2. In the above circumstances there is a slight difference in the figures of population as arrived at by an earlier sorting of the slips and as now determined by counting from the National Citizens' Register. This difference has been accen tuated by an order passed by me during the later count. -

ALLAHABAD Address: 38, M.G

CGST & CENTRAL EXCISE COMMISSIONERATE, ALLAHABAD Address: 38, M.G. Marg, Civil Lines, Allahabad-211 001 Phone: 0532-2407455 E mail:[email protected] Jurisdiction The territorial jurisdiction of CGST and Central Excise Commissionerate Allahabad, extends to Districts of Allahabad, Banda, Chitrakoot, Kaushambi, Jaunpur, SantRavidas Nagar, Pratapgarh, Raebareli, Fatehpur, Amethi, Faizabad, Ambedkarnagar, Basti &Sultanpurof the state of Uttar Pradesh. The CGST & Central Excise Commissionerate Allahabad comprises of following Divisions headed by Deputy/ Assistant Commissioners: 1. Division: Allahabad-I 2. Division: Allahabad-II 3. Division: Jaunpur 4. Division: Raebareli 5. Division: Faizabad Jurisdiction of Divisions & Ranges: NAME OF JURISDICTION NAME OF RANGE JURISDICTION OF RANGE DIVISION Naini-I/ Division Naini Industrial Area of Allahabad office District, Meja and Koraon tehsil. Entire portion of Naini and Karchhana Area covering Naini-II/Division Tehsil of Allahabad District, Rewa Road, Ranges Naini-I, office Ghoorpur, Iradatganj& Bara tehsil of Allahabad-I at Naini-II, Phulpur Allahabad District. Hdqrs Office and Districts Jhunsi, Sahson, Soraon, Hanumanganj, Phulpur/Division Banda and Saidabad, Handia, Phaphamau, Soraon, Office Chitrakoot Sewait, Mauaima, Phoolpur Banda/Banda Entire areas of District of Banda Chitrakoot/Chitrako Entire areas of District Chitrakoot. ot South part of Allahabad city lying south of Railway line uptoChauphatka and Area covering Range-I/Division Subedarganj, T.P. Nagar, Dhoomanganj, Ranges Range-I, Allahabad-II at office Dondipur, Lukerganj, Nakhaskohna& Range-II, Range- Hdqrs Office GTB Nagar, Kareli and Bamrauli and III, Range-IV and areas around GT Road. Kaushambidistrict Range-II/Division Areas of Katra, Colonelganj, Allenganj, office University Area, Mumfordganj, Tagoretown, Georgetown, Allahpur, Daraganj, Alopibagh. Areas of Chowk, Mutthiganj, Kydganj, Range-III/Division Bairahna, Rambagh, North Malaka, office South Malaka, BadshahiMandi, Unchamandi. -

Evolution of Sarasvati in Sanskrit Literature

EVOLUTION OF SARASVATI IN SANSKRIT LITERATURE ABSTRACT SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SANSKRIT BY MOHD. iSRAIL KHAN UNDER THE SUPERVISDN OF Dr. R. S. TRIPATHI PROF. & HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SANSKRIT ALTGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY A L I G A R H FACULTY OF ARTS ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1969 ABSTRACT The Hindu mythology is predominontly polytheistic. Gods are numerous and each god or goddess shows very often mutually irreconcilable traits within him or her. This is equally true of Sarasvati, too. She is one of female deities of the Rgvedic times. She has got many peculiarities of her own resulting in complexity of her various conceptions through the ages. In the Rgvedic pantheon, among female deities, Usas, the daughter of the heaven is (divo duhita)/given an exalted place and has been highly extolled as a symbol of poetic beauty. Sarasvati comes next to her in comparison to other Rgvedic goddesses. But in the later period, Usas has lost her superiority and Sarasvati has excelled her. The superiority of Sarasvati is also obvious from another instance. In the Vedic pantheon, many ideitiet s arose and later on merged into others. If any one of them survived,/was mostly in an sterio- typed form. But with Sarasvati, there has been a gradual process of change and development. In her earliest stage, she was a spacious stream having rythmic flow and congenial waters. It was, therefore, but natural that it arrested the attention of seers dwelling along with its banks. They showed their heart-felt reverence to her. -

ESSENCE of VAMANA PURANA Composed, Condensed And

ESSENCE OF VAMANA PURANA Composed, Condensed and Interpreted By V.D.N. Rao, Former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Union Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India 1 ESSENCE OF VAMANA PURANA CONTENTS PAGE Invocation 3 Kapaali atones at Vaaranaasi for Brahma’s Pancha Mukha Hatya 3 Sati Devi’s self-sacrifice and destruction of Daksha Yagna (Nakshatras and Raashis in terms of Shiva’s body included) 4 Shiva Lingodbhava (Origin of Shiva Linga) and worship 6 Nara Narayana and Prahlada 7 Dharmopadesha to Daitya Sukeshi, his reformation, Surya’s action and reaction 9 Vishnu Puja on Shukla Ekadashi and Vishnu Panjara Stotra 14 Origin of Kurukshetra, King Kuru and Mahatmya of the Kshetra 15 Bali’s victory of Trilokas, Vamana’s Avatara and Bali’s charity of Three Feet (Stutis by Kashyapa, Aditi and Brahma & Virat Purusha Varnana) 17 Parvati’s weds Shiva, Devi Kaali transformed as Gauri & birth of Ganesha 24 Katyayani destroys Chanda-Munda, Raktabeeja and Shumbha-Nikumbha 28 Kartikeya’s birth and his killings of Taraka, Mahisha and Baanaasuras 30 Kedara Kshetra, Murasura Vadha, Shivaabhisheka and Oneness with Vishnu (Upadesha of Dwadasha Narayana Mantra included) 33 Andhakaasura’s obsession with Parvati and Prahlaad’s ‘Dharma Bodha’ 36 ‘Shivaaya Vishnu Rupaaya, Shiva Rupaaya Vishnavey’ 39 Andhakaasura’s extermination by Maha Deva and origin of Ashta Bhairavaas (Andhaka’s eulogies to Shiva and Gauri included) 40 Bhakta Prahlada’s Tirtha Yatras and legends related to the Tirthas 42 -Dundhu Daitya and Trivikrama -

Reinventing Sati and Sita: a Study of Amish Tripathi's Central Women Characters from a Feminist Perspective Abstract

ADALYA JOURNAL ISSN NO: 1301-2746 Reinventing Sati and Sita: A Study of Amish Tripathi’s Central Women Characters from a Feminist Perspective T.V. Sri Vaishnavi Devi [email protected] 9043526179 Assistant Professor and Research Scholar Department of English (UG Aided) Nallamuthu Gounder Mahalingam College Pollachi. Dr. A.Srividhya 9894086190 [email protected] Assistant Professor and Research Supervisor Department of English (UG Aided) Nallamuthu Gounder Mahalingam College Pollachi. Abstract In the age old mythical narratives, women were seen from the androcentric perspective and were portrayed as creatures that are inferior to men by all means. The customs and traditions created by the patriarchal world suppressed women to an extent where she become a dumb doll, unable to express her talents and capabilities. Revisioning myth interprets the myth from a new angle. Revisioning mythmaking is one of the emerging trends in literature at present. The critical discourse of revisionist mythmaking attempts to revision, reinterpret and reconstruct the age-old myth from a feminist perspective. It gives voice to the voiceless beings and challenges the patriarchal notions of feminine identity. Amish Tripathi, India’s first literary pop star and a contemporary Indian myth maker, rereads and rewrites the ancient Indian epics by utilizing the strategy of revisionist myth-making. This paper examines the way Amish Tripathi has subverted the androcentric mythical narratives by creating a new identity for the mythical woman characters, Sati and Sita. It traces the challenges faced by these central women characters and highlights bravery and efficacy as leaders which help them to undermine the power structures of male-dominated society. -

Devi: the Great Goddess (Smithsonian Institute)

Devi: The Great Goddess Detail of "Bhadrakali Appears to Rishi Chyavana." Folio 59 from the Tantric Devi series. India, Punjab Hills, Basohli, ca 1660-70. Opaque watercolor, gold, silver, and beetle-wing cases on paper. Purchase, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution F1997.8 Welcome to Devi: The Great Goddess. This web site has been developed in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name. The exhibition is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery from March 29, 1999 through September 6, 1999. Like the exhibition, this web site looks at the six aspects of the Indian goddess Devi. The site offers additional information on the contemporary and historical worship of Devi, activities for children and families, and a list of resources on South Asian arts and cultures. You may also want to view another Sackler web site: Puja: Expressions of Hindu Devotion, an on-line guide for educators explores Hindu worship and provides lesson plans and activities for children. This exhibition is made possible by generous grants from Enron/Enron Oil & Gas International, the Rockefeller Foundation, The Starr Foundation, Hughes Network Systems, and the ILA Foundation, Chicago. Related programs are made possible by Victoria P. and Roger W. Sant, the Smithsonian Educational Outreach Fund, and the Hazen Polsky Foundation. http://www.asia.si.edu/devi/index.htm (1 of 2) [7/1/2000 10:06:15 AM] Devi: The Great Goddess | Devi Homepage | Text Only | | Who is Devi | Aspects of Devi | Interpreting Devi | Tantric Devi | For Kids | Resources | | Sackler Homepage | Acknowledgements | The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560.