Learning from Ethicists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DENSHO PUBLICATIONS Articles by Kelli Y

DENSHO PUBLICATIONS Articles by Kelli Y. Nakamura Kapiʻolani Community College Spring 2016 Byodo-In by Rocky A / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 The articles, by Nakamura, Kelli Y., are licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 by rights owner Densho Table of Contents 298th/299th Infantry ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Alien Enemies Act of 1798 ........................................................................................................................... 3 Americans of Japanese Ancestry: A Study of Assimilation in the American Community (book) ................. 6 By: Kelli Y. Nakamura ................................................................................................................................. 6 Cecil Coggins ................................................................................................................................................ 9 Charles F. Loomis ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Charles H. Bonesteel ................................................................................................................................... 13 Charles Hemenway ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Dan Aoki .................................................................................................................................................... -

Kansas – Point of Know Return Live

Kansas – Point Of Know Return Live & Beyond (43:41 + 68:31, CD, Digital, Vinyl, InsideOut Music / Sony Music, 2021) Nach diversen Umbesetzungen vor einigen Jahren ist das amerikanische Progschlachtschiff Kansas wieder schwer auf Kurs. Man legte nach dem geglückten Neustart mit The„ Prelude Implicit“ (2016) und besonders „The Absence Of Presence“ (2020) nicht nur zwei prächtige Studioalben vor, auch live präsentiert sich die Band nach der alterstechnischen Blutauffrischung vitaler denn je. Deswegen geht ebenfalls „Live & Beyond“ in die zweite Runde. Vor rund drei Jahren würdigte man bereits den 76er Klassiker „Leftoverture“ in seiner Gesamtheit im Livekontext, jetzt folgt der zweite, ebenfalls verkaufstechnisch sehr erfolgreiche Platinum Seller „Point Of Know Return“. Wies das erste „Live & Beyond“ Package noch einige Makel auf, besonders durch die massive Verwendung von Autotune bei den Gesangspassagen, so macht die Band dieses Mal alles richtig. Gerade der Steve Walsh Nachfolger Ronnie Platt hat anscheinend wesentlich mehr an Vertrauen in seine eigene Stimmkraft gewonnen und liefert eine perfekte Performance voller vokaler Leidenschaft ab. Natürlich gibt es einige Überschneidungen mit dem letzten Livepackage, da man eben nicht grundsätzlich auf „Leftoverture“ Klassiker wie ‚The Wall‘, ‚Miracles Out Of Nowhere‘ und dem unverwüstlichen ‚Carry On Wayward Son‘ verzichten wollte. Doch neben dem kompletten 77er Album „Point Of Know Return“ bietet man einen sehr gut austarierten Mix aus Klassikern, neuem Material (u.a. ‚Summer‘ und ‚Refugee‘ von „The Prelude Implicit“), aber auch selten gehörtes Material wie das äußerst dynamisch interpretierte ‚Two Cents Worth‘ von „Masque“ (1975) oder die ursprünglich vonSteve Morse geprägten ‚Musicatto / Taking In The View‘ von „Power“ (1986). Was aber in erster Linie überzeugt, ist die Hingabe, Spielfreude und unglaubliche Power, die die aktuelle Kansas Besetzung auf der Bühne bietet. -

Lita Ford and Doro Interviewed Inside Explores the Brightest Void and the Shadow Self

COMES WITH 78 FREE SONGS AND BONUS INTERVIEWS! Issue 75 £5.99 SUMMER Jul-Sep 2016 9 771754 958015 75> EXPLORES THE BRIGHTEST VOID AND THE SHADOW SELF LITA FORD AND DORO INTERVIEWED INSIDE Plus: Blues Pills, Scorpion Child, Witness PAUL GILBERT F DARE F FROST* F JOE LYNN TURNER THE MUSIC IS OUT THERE... FIREWORKS MAGAZINE PRESENTS 78 FREE SONGS WITH ISSUE #75! GROUP ONE: MELODIC HARD 22. Maessorr Structorr - Lonely Mariner 42. Axon-Neuron - Erasure 61. Zark - Lord Rat ROCK/AOR From the album: Rise At Fall From the album: Metamorphosis From the album: Tales of the Expected www.maessorrstructorr.com www.axonneuron.com www.facebook.com/zarkbanduk 1. Lotta Lené - Souls From the single: Souls 23. 21st Century Fugitives - Losing Time 43. Dimh Project - Wolves In The 62. Dejanira - Birth of the www.lottalene.com From the album: Losing Time Streets Unconquerable Sun www.facebook. From the album: Victim & Maker From the album: Behind The Scenes 2. Tarja - No Bitter End com/21stCenturyFugitives www.facebook.com/dimhproject www.dejanira.org From the album: The Brightest Void www.tarjaturunen.com 24. Darkness Light - Long Ago 44. Mercutio - Shed Your Skin 63. Sfyrokalymnon - Son of Sin From the album: Living With The Danger From the album: Back To Nowhere From the album: The Sign Of Concrete 3. Grandhour - All In Or Nothing http://darknesslight.de Mercutio.me Creation From the album: Bombs & Bullets www.sfyrokalymnon.com www.grandhourband.com GROUP TWO: 70s RETRO ROCK/ 45. Medusa - Queima PSYCHEDELIC/BLUES/SOUTHERN From the album: Monstrologia (Lado A) 64. Chaosmic - Forever Feast 4. -

Tom Brislin – 30-Day Keyboard Workout

30-Day Keyboard Workout by Tom Brislin Tom Brislin has had a varied career. He achieved critical success with his band, Spiraling, and he has garnered considerable attention as a sideman with Yes, Camel, Renaissance, Deborah Harry (of Blondie fame) and Meatloaf. In fact, he is on the road again with Meatloaf this summer, so if you catch that band on tour, that is Tom handling the keyboards. Brislin is not only a sought after keyboard sideman, but also a classically trained educator, and it shows in his book 30-Day Keyboard Workout , published by Alfred Music. The book is divided into five sections. First, we have basic terms and symbols that every pianist should know. The second section is all about warming up, hand position, posture – necessities often overlooked by pianists. This is followed by a brief series of warm-up exercises. Sections four and five are the meat of the book. The Proficiency Workout is intended for intermediate players, while the Extended Proficiency Workout is for more advanced players. The idea is to play the warm-ups and the daily exercises within a one- month period. That can be a daunting task, so don’t feel the need to take the book’s title literally. Brislin even suggests being flexible, and he offers a list of optional approaches to practicing the exercises. However you decide to accomplish the workout, take our time, enjoy it, and get it right. The keyword in describing this book is comprehensive . 30-Day Keyboard Workout covers chromatic scales, major and minor scales, and various chords and arpeggios. -

Hatcher, Allen Win in Gary, Sb No Parietal Hour

5(: vol. II, no. XXII University of Notre Dame November 9, 1967 HATCHER, ALLEN WIN IN GARY, SB that the dead people didn't vote, stant cliffhanger. Mrs. Hicks, an for he won by barely two thou adament opponent of school bus A Negro Democrat won in sand votes. sing, was defeated by ten thou Gary while a Polish Democrat In South Bend, the margin sand votes by Massachusetts Sec was buried in South Bend. Rich was much wider. Allen ran a full retary of State Kevin White. ard Hatcher, a Negro city coun ten thousand votes ahead of In other results around the cilman, overcame both the Re Pajakowski, even doing better country, segregationist Congress publican party and his own par than expected in the heavily man John Bell Williams was e ty's organization to win in Gary. Democratic 2nd and 6th Wards. lected Governor of Mississippi, Republican Mayor Lloyd Allen The Democratic nominee won defeating Republican Rubel! in South Bend benefited from but 36% of the vote (6% went Phillips. Kentucky, for the first unusual support in Negro wards to two independants in the race). time in 20 years, elected a Re as he piled up 56% of the vote The Reformer, South Bend's new publican Governor, former Cir in South Bend. newspaper, endorsed the GOP cuit Court judge Louie Nunn. The Gary election was held Mayor over his Democratic op San Francisco's election saw a with the National Guard standing ponent. Allen carried Republican referendum on Vietnam, with a by and a large number of people, City Clerk nominee Cecil Blough stop-the-bombing-and-begin-with including a contingent of Notre in with him, although Democrat drawal motion placed before the Dame students, watching the George Herendeen was elected voters. -

Rock Band Kansas to ‘Carry On’ Tour in Celebration of Anniversary of Iconic Album… Point of Know Return

Media Contact: Casey Blake 480-644-6620 [email protected] ROCK BAND KANSAS TO ‘CARRY ON’ TOUR IN CELEBRATION OF ANNIVERSARY OF ICONIC ALBUM… POINT OF KNOW RETURN SEXTUPLE-PLATINUM ALBUM TO BE PERFORMED IN ITS ENTIRETY Nashville, TN – April 8, 2019 – America’s preeminent progressive rock band, KANSAS, will be touring select cities in the United States and Canada in during the fall and winter, on the third leg of their popular Point of Know Return Anniversary Tour. Launched as a celebration of the 40th Anniversary of the massive hit album Point of Know Return, the band will be performing the album in its entirety. The tour showcases more than two hours of classic KANSAS music including hit songs, deep cuts, and fan favorites. Tickets and KANSAS VIP Packages for most dates go on sale to the general public Friday, April 12, 2019. Ticket information can be found at www.kansasband.com. Currently in the midst of its second leg of the tour, the KANSAS: Point of Know Return Anniversary Tour premiered September 28, 2018 in Atlanta, GA. The tour has already performed to large and enthusiastic audiences in cities including Atlanta, GA; Nashville, TN; Pittsburgh, PA; Chicago, IL; St. Louis, MO; Kansas City, MO; San Antonio, TX; Dallas, TX; Indianapolis, IN; Worcester, MA; Clearwater, FL; Ft. Lauderdale, FL; Baltimore, MD; Denver, CO; San Diego, CA; and Los Angeles, CA. In 1977, KANSAS followed up the success of Leftoverture by releasing the album Point of Know Return. Containing the smash hit and million-selling single “Dust in the Wind,” along with fan favorites such as “Portrait (He Knew),” “Closet Chronicles,” and “Paradox,” Point of Know Return became the band’s greatest selling studio album. -

October 2020 New Releases

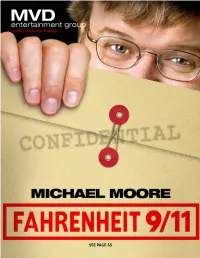

October 2020 New Releases SEE PAGE 55 what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 67 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 13 FEATURED RELEASES Video ANDREAS THE RESIDENTS - KIM WILSON - 39 VOLLENWEIDER- CUBE-E BOX TAKE ME BACK Film QUIET PLACES Films & Docs 40 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 65 Order Form 74 Deletions & Price Changes 72 THE OUTLAWS - THE LAST STARFIGHTER FAHRENHEIT 9/11 800.888.0486 LIVE AT ROCKPALAST 1981 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 www.MVDb2b.com THE DEAD MILKMEN - ANDREAS VOLLENWEIDER- OKEY DOKEY - (WE DON’T NEED THIS) FASCIST QUIET PLACES ONCE UPON ONE TIME GROOVE THANG (2ND PRESSING) OCTOBER HEAT WAVE! MVD turns up the hotness with FAHRENHEIT 9/11, the #1 best-selling documentary of all time! Available on DVD, and for the first time on bluray! Watch as Michael Moore bushwhacks his way through this controversial film about the relation between money, oil and the 9/11 tragedy, graced with a dash of satire. This new issue comes with lots of bonus features, reversible artwork and limited edition slipcover, scorching any prior version. While FAHRENHEIT’s temperature is elevated, ARROW VIDEO chills us with the limited bluray of COLD LIGHT OF DAY, a retelling of British serial killer Des Nilsen’s grisly story. Arrow’s THE DEEPER YOU DIG finds a body hidden in the cold, hard ground, only to have the murderer’s head burrowed into by the victim! A real headache! THE LAST STARFIGHTER, the 1984 Sci-Fi opus, gets the Arrow treatment this month, showing the computer whizz kid fighting an interstellar war with a new 4K scan and a stunning sound mix. -

Halls Push, Administration Drags, Tumult Develops Over Parietal Hrs

THE OBSERVERs< University of Notre Dame volume II, no. XVIII October 30, 1967 Halls Push, Administration Drags, Tumult Develops Over Parietal Hrs In the past week, new rumors tained that, while the matter has Rev. Charles I. M cCarragher, a section meeting that big bro have come to light regarding been discussed, he doubts that Vice President for Student A f ther would be watching. possibly another “ plot” pertain any members o f the Hall Presi fairs. Notoriety came too soon The Observer contacted Cam ing to the question o f parietal dents’ Council “ would go that and the plan lost support and pus Security Sunday afternoon hours. The Farley Hall Council far.” According to the Commis petered out. regarding the reports and was re discussed the issue last week, sioner, the plan for the ads in The issue o f parietal hours warded with the answer: “ Let’s and Hall Life Commissioner Chicago papers came up in remains much discussed after put it this way. We don’t know Tom Brislin admits that the mat spring o f 1966 among Seniors last spring's abortive effort. Prior anything about it. If we did ter has come up in meetings of then pressing for curfew chang to this weekend, there were rum know, we wouldn’t tell you.” the Hall Presidents’ Council. es. Brislin says that it was simply ors that Campus Security was The Observer was also denied Details o f the new plan, as discussed in the past tense. going to have Morrissey Hall un access to the police blotter with discussed in at least two section Last spring, a plan came to der close scrutiny. -

Little Phatty Manual

Stage II Edition Table of Contents FOREWORD from Mike Adams ............................... 4 THE USER INTERFACE (con’t) Performance Sets ................................................................ 50 THE BASICS Activating the Arpeggiator and Latch .................... 52 How to use this Manual ....................................... 5 How the LP handles MIDI ............................................. 54 Setup and Connections ........................................ 5 Overview and Features ........................................ 7 APPENDICES Signal Flow .................................................................... 9 A – Master Mode Menu Tree ...................................... 58 Basic Operation ......................................................... 10 B – LFO Sync Modes ..................................................... 59 C – Arpeggiator Clock Source ................................. 60 THE COMPONENTS D – The Calibration Preset ........................................ 61 A. Oscillator Section ............................................... 11 E – Accessories ................................................................. 62 B. Filter Section ......................................................... 13 F – Tutorial ............................................................................. 63 C. Envelope Generators Section .................... 15 G – MIDI Implementation Chart ............................ 68 D. Modulation Section .......................................... 17 H – Service & Support Information -

17 3Rd WORLD ELECTRIC (Feat. Roine Stolt)

24-7 SPYZ 6 – 8 3rd AND THE MORTAL Painting on glass - 17 3rd WORLD ELECTRIC (feat. Roine Stolt) Kilimanjaro secret brew digipack - 18 3RDEGREE Ones & zeros: volume I - 18 45 GRAVE Only the good die young – 18 46000 FIBRES )featuring Nik Turner) Site specific 2CD – 20 48 CAMERAS Me, my youth & a bass drum – 17 A KEW’S TAG Silence of the sirens - 20 A LIQUID LANDSCAPE Nightinagel express – 15 A LIQUID LANDSCAPE Nightingale express digipack – 17 A NEW’S TAG Solence of the sirens – 18 A SILVER MT ZION Destroy all dreamers on / Debt 6 depression digipack – 10 A SPIRALE Come una lastra – 8 AARDVARK (UK) Same - 17 ABACUS European stories (new album) – 17 ABDULLAH Graveyard poetry – 10 ABDULLAH Same – 10 ABIGAIL'S GHOST Black plastic sun - 18 ABRAXIS Same – 17 ABRETE GANDUL Enjambre sismico – 16 ABYSMAL GRIEF Feretri – 16 ABYSMAL GRIEF Reveal nothing - 16 ABYSMAL GRIEF Strange rites of evil – 16 AC/DC Let there be rock DVD Paris 1979 - 15 AC/DC Back in black digipack – 16 AC/DC Rock or bust – 21 AC/DC The razor’s edge digipack – 16 ACHE Green man / De homine urbano – 17 ACHIM REICHEL & MACHINES Echo & A. R. IV 2CD - 23 ACHIM REICHEL Grüne reise & Erholung - 17 ACID BATH Pagan terrorism tactics – 10 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE MELTING PARAISO U.F.O. Live in occident digipack – 17 ACINTYA La citè des dieux oublies – 18 ACQUA FRAGILE Mass media stars (Esoteric) - 18 ACQUA FRAGILE Same (Esoteric) – 18 ACTIVE HEED Higher dimensions – 18 ADEKAEM Same – 20 ADICTS Smart alex – 17 ADICTS Sound of music – 17 ADMIRAL SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVELL Don’t hear it…fear it (Rise Above) – 18 ADRIAN SHAW & ROD GOODWAY Oxygen thieves digipack – 15 ADRIAN SHAW Colours - 17 ADRIANO MONTEDURO E LA REALE ACCADEMIA DI MUSICA Same (Japanes edition) – 18 ADTVI La banda gastrica – 8 ADVENT Silent sentinel digisleeve – 18 AELIAN A tree under the colours – 8 AEONSGATE Pentalpha – 17 AEROSMITH Live and F.I.N.E. -

The Voice of Notre Dame

,. ' - 'll'liJJIE Tillich Praises Council For Emphasis on Faith "-!- The Ecumenical Council and the discussion. Pope john the XXlll were.both After an hour of panel dis OJF .NOTBE li!JAMIIE praised by eminent Protestant cussion, the audience was allow theologian, Dr. Paul Tillich, of ed to participate, Questions the University of Chicago Divi ranged over ideas of the Sacra nity School, in a panel discussion Volume 3, Number 7 Notre Dame, Indiana November 11, 1964 ments, myths of the Bible and here last Wednesday. the relationship between God and He gave the plau~ts for the part Man, both played in the ''emphasizing Dr, Tillich returned the same N.Do· Freshmall 'Arrested' of the 'experience' of faith." Dr. night to participate in a second Tillich holds that belief is like discussion, mainly for the ' historical facts as true because of faculty. confidence in someone' s writing While Watching Polls while faith goes deeper in that it A Notre Dame freshman was cial's know he was there, When' a many attempts to vote by people is an "experience" that goes on taken i~o custody by Gary, Ind., voter is challenged, he may still who were not registered. ''There within a person. police as a result of his part!- vote, but to do so must sign an was one girl who could no; have The peppery and smiling Dr. i cipation in a Young .Republican affidavit that he is a legal voter, been more than 16. She gave the Tillich also placed great stress !> poll-watching project in Lake Signing afalseaffidavitisacrim- name of a woman-registered as On the necessary "de-literaliza County, Indiana, last Tuesday, inal offense, 60 'years old.'' Several people tion" now goingonwithingChris Tom Moore, from River Forest, Moore says that this was the tried to vote twice, he said. -

Time, Ethics, & the Films of Christopher Nolan

Time, Ethics & the Films of Christopher Nolan Tom Brislin University of Hawai‘i © 2016 Our conception of ethics is bound in time. Whether we move from intention to action, action to consequence, or advance a set of virtues as a context for reflection, time is unidirectional. We are temporal creatures, measuring time in discrete units. We are aware of time passing, and of its impermanence. We put things in the past, live for the present, plan for the future. The syntax and techniques of filmmaking provide the means to manipulate the confines of conventional time in both story and story-telling. What happens when we change our conception of time? Does it stretch or compress our fundamental ethical thinking? Does it force us into a reconsideration from a new “starting point?” We visualize time in many ways, always moving forward. A stopwatch ticking off its discrete micro-units; the sun rising and setting to mark the passage of a day; a photo album in which images mark the advancing age of ourselves and others. We classify events as occurring consecutively, concurrently – or in digital terms synchronously or asynchronously – and in “real time.” What If … What Is When time is skewed, does the flow of ethics likewise bend and reshape? Film director and writer Christopher Nolan has attained distinction for his manipulations of time in narrative structure, story theme, and filmic technique. A review of a selection of his films offers the opportunity to challenge our ethical theories against the “what if,” giving them new perspectives on application