The Way of the Fight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Iowa Wrestling 1993-94

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Athletics Media Guides Athletics 1994 Northern Iowa Wrestling 1993-94 University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1993 Athletics, University of Northern Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Northern Iowa, "Northern Iowa Wrestling 1993-94" (1994). Athletics Media Guides. 198. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg/198 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Athletics Media Guides by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home of the 1993-94 Media Information Northern Iowa at a Glance Contents Location ............................................................. Cedar Falls, Iowa 50614 1993-94 Outlook ......................2 -3 Founded ............................................................. 1876 Enrollrnent.. ....................................................... 12,800 Coaching Staff .........................4 -5 Nicknarne ...........................................................P anthers School Colors ................................................... Purple & Old Gold 1993-94 Roster ........................... 6 President ............................................................Dr . Constantine Curris Athletic Director .............................................. Chris Ritrievi -

Ufc Welterweight Champion Woodley and Retired Contender Florian Serve As Desk Analysts with Host Bryant for Fs1 Ufc Fight Night: Maia Vs

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: John Stouffer Wednesday, May 16, 2018 [email protected] UFC WELTERWEIGHT CHAMPION WOODLEY AND RETIRED CONTENDER FLORIAN SERVE AS DESK ANALYSTS WITH HOST BRYANT FOR FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: MAIA VS. USMAN No. 1 Flyweight Contender Shevchenko Makes Analyst Debut with Former UFC Heavyweight Champion Werdum and Santiago on FOX Deportes LOS ANGELES – Today, FOX Sports announces UFC welterweight champion Tyron Woodley and retired contender Kenny Florian to serve as desk analysts alongside lead UFC host Karyn Bryant for FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: MAIA VS. USMAN programming on Friday, May 18 and Saturday, May 19. Blow-by-blow announcer Brendan Fitzgerald and veteran MMA analyst Jimmy Smith call the bouts live Octagon-side from Santiago, Chile. Laura Sanko adds reports and interviews fighters on-site. In addition, No. 1-ranked flyweight contender Valentina Shevchenko makes her analyst debut alongside former UFC heavyweight champion Fabricio Werdum and Troy Santiago calling the fights in Spanish on FOX Deportes. Two elite welterweights headline UFC’s first visit to Chile as Kamaru Usman (11-1) faces former title challenger Demian Maia (25-8) in a five-round main event in Santiago. Winner of 11 bouts in a row, including seven in the Octagon over the likes of Leon Edwards and Sergio Moraes, the No. 7-ranked Usman has been a nightmare matchup for everyone he’s faced. He expects similar results against the Brazilian grappling wizard Maia, the No. 5 contender at 170 pounds, who owns wins against top contenders Jorge Masvidal, Carlos Condit, Matt Brown, Neil Magny and Gunnar Nelson. -

Youth Participation and Injury Risk in Martial Arts Rebecca A

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Youth Participation and Injury Risk in Martial Arts Rebecca A. Demorest, MD, FAAP, Chris Koutures, MD, FAAP, COUNCIL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS The martial arts can provide children and adolescents with vigorous levels abstract of physical exercise that can improve overall physical fi tness. The various types of martial arts encompass noncontact basic forms and techniques that may have a lower relative risk of injury. Contact-based sparring with competitive training and bouts have a higher risk of injury. This clinical report describes important techniques and movement patterns in several types of martial arts and reviews frequently reported injuries encountered in each discipline, with focused discussions of higher risk activities. Some This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have of these higher risk activities include blows to the head and choking or fi led confl ict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any confl icts have been resolved through a process submission movements that may cause concussions or signifi cant head approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of injuries. The roles of rule changes, documented benefi ts of protective Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication. equipment, and changes in training recommendations in attempts to reduce Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefi t from injury are critically assessed. This information is intended to help pediatric expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external health care providers counsel patients and families in encouraging safe reviewers. -

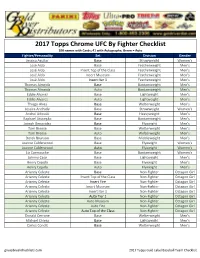

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

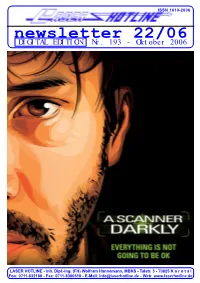

Newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 22/06 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 193 - Oktober 2006 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 22/06 (Nr. 193) Oktober 2006 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, diesem Sinne sind wir guten Mutes, unse- liebe Filmfreunde! ren Festivalbericht in einem der kommen- Kennen Sie das auch? Da macht man be- den Newsletter nachzureichen. reits während der Fertigstellung des einen Newsletters große Pläne für den darauf Aber jetzt zu einem viel wichtigeren The- folgenden nächsten Newsletter und prompt ma. Denn wer von uns in den vergangenen wird einem ein Strich durch die Rechnung Wochen bereits die limitierte Steelbook- gemacht. So in unserem Fall. Der für die Edition der SCANNERS-Trilogie erwor- jetzt vorliegende Ausgabe 193 vorgesehene ben hat, der darf seinen ursprünglichen Bericht über das Karlsruher Todd-AO- Ärger über Teil 2 der Trilogie rasch ver- Festival musste kurzerhand wieder auf Eis gessen. Hersteller Black Hill ließ Folgen- gelegt werden. Und dafür gibt es viele gute des verlautbaren: Gründe. Da ist zunächst das Platzproblem. Im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes ”platzt” der ”Käufer der Verleih-Fassung der Scanners neue Newsletter wieder aus allen Nähten. Box haben sicherlich bemerkt, dass der Wenn Sie also bislang zu jenen Unglückli- 59 prall gefüllte Seiten - und das nur mit zweite Teil um circa 100 Sekunden gekürzt chen gehören, die SCANNERS 2 nur in anstehenden amerikanischen Releases! Des ist. -

Bantamweight Superstar 'The California Kid' Urijah Faber

BANTAMWEIGHT SUPERSTAR ‘THE CALIFORNIA KID’ URIJAH FABER MEETS SCOTT ‘YOUNG GUNS’ JORGENSEN ON APRIL 13 AT MANDALAY BAY IN LAS VEGAS Las Vegas, Nevada – Fresh off a brilliant submission victory over Ivan Menjivar at UFC 157, “The California Kid” Urijah Faber returns to the Octagon® Saturday, April 13 at the Mandalay Bay Events Center in Las Vegas to meet Scott Jorgensen in a can’t-miss bantamweight showdown. Faber, the former WEC featherweight champion ranked second in the bantamweight division, is known for his explosive athleticism and finishing ability, and the 33-year-old Sacramento native owns wins over the likes of Jens Pulver (twice), Raphael Assuncao, Takeya Mizugaki, Eddie Wineland and Brian Bowles. A three-time Pac-10 wrestling champion at Boise State University, the 30-year-old Jorgensen defeated John Albert in a performance that earned him Fight and Submission of the Night honors in his most recent bout this past December. “Young Guns” also holds notable victories over Jeff Curran and Brad Pickett and has developed a reputation as one of the division’s most exciting fighters. “Urijah Faber is one of the best bantamweights in the world and he proved it at UFC 157 by submitting Ivan Menjivar in the first round,” UFC President Dana White said. “He’s ready to jump right back in the Octagon on April 13 with Scott Jorgensen, who’s ranked seventh in the world at 135 pounds. Both of these guys like to finish fights. This is a really exciting main event for the TUF Finale!” In addition to the Faber-Jorgensen main event, this season’s The Ultimate Fighter® winner will be crowned when the Octagon® makes its way back to the Mandalay Bay Events Center. -

2014-15 Wrestling

OHIO STATE ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS Fawcett Center, 6th Floor | 2400 Olentangy River Rd. | Columbus, Ohio 43210 2014-15 WRESTLING COLUMBUS, Ohio - Coming off a three-week layoff, the seventh-ranked Ohio State 4-1 Overall; 0-0 Big Ten wrestling team ushers in 2015 with a showdown in its Big Ten opener against top-ranked NOV 02 at Michigan St. Open NTS Iowa on Sunday inside St. John Arena. The match is set for 2 p.m. and can be seen live on 13 KENT STATE W, 38-3 BTN+ (subscription required). 15 vs. Army^ W, 37-6 15 vs. Arizona State^ W, 30-10 PARKING ADVISORY 23 at Virginia Tech L, 19-18 24 at Virginia W, 30-7 Fans are encouraged to arrive at St. John Arena early on Sunday (doors open at 1 p.m.) and refer to the following link for a parking map: http://grfx.cstv.com/schools/osu/graphics/pdf/ DEC 05 CKLV Invitational 1 2nd/39 facilities/wrestl-parking.pdf 06 CKLV Invitational 1 14 MISSOURI L, 20-19 BUCKEYES IN A NUTSHELL JAN 04 IOWA* 2 p.m. 11 PENN STATE* 2 p.m. • Ranked seventh in this week’s USA Today/NWCA poll, Ohio State is 4-2 on the year with 16 at Michigan State* 7 p.m. wins over Kent State, Army, Arizona State and Virginia. 18 at Michigan* 2 p.m. • In its last dual meet action, the Buckeyes were edged by fifth-ranked Missouri, 20-19, on 23 INDIANA* 2 7 p.m. tiebreaker criteria. Ohio State won five of 10 matches, including a 15-5 major decision victory 25 at Maryland* Noon 30 PURDUE* 7 p.m. -

Octagon™: the Exhibition

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Amy Schmidt, (702) 810-0685 [email protected] MCQ Fine Art Advisory and Ultimate Fighting Championship® Present Octagon™: The Exhibition Photographer Kevin Lynch captures the intensity of mixed-martial arts on film (May 12, 2008) Michele C. Quinn Fine Art Advisory and Zuffa, LLC, owner of the UFC brand, are pleased to announce the opening of Octagon: The Exhibition, a show of more than 20 chromogenic prints culled from the limited-edition Octagon book published by Zuffa, LLC, and powerHouse Books. The exhibition opens Memorial Day weekend in dual exhibition spaces; the MCQ Salon located at 620 S. 7th St. and Soho Lofts located at 900 Las Vegas Blvd. S. A photographic narrative of Ultimate Fighting Championship®, Octagon dramatically documents UFC’s mixed martial arts fighters moments before, during and after their intense matches in the Octagon™. Los Angeles-based photographer Kevin Lynch was given unprecedented access behind-the-scenes of this hugely popular sport over a four-year period in order to capture the rawness of the fighters and their fights. Lynch used a globe light in order to best emulate locker-room light—“it’s not really a flattering light,” says Lynch, “but it’s a very honest light.” While Lynch had the blessing of UFC owners Lorenzo Fertitta and Frank Fertitta III as well as President Dana White, when he was in the locker room it was clear that he was on his own. Eventually he gained the fighters’ trust and respect; still “the hard part was to get the ‘after’ pictures from some of these fighters,” adds Lynch. -

Mixed Martial Arts, Bullying, and Sociolegal Quandaries

EFFECTIVE AGGRESSIVENESS AND INCONSISTENCIES IN THE BIJURIDICAL TREATMENT OF AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOUR: MIXED MARTIAL ARTS, BULLYING, AND SOCIOLEGAL QUANDARIES Sara Gwendolyn Ross* One of the most legally restricted elements of human nature is that of aggression and the intent to harm.** Yet in combat sports such as mixed-martial arts (“MMA”) or boxing, one of the key elements in judging a fighter’s performance to determine a winner is “effective aggressiveness”. MMA used to be characterized by the pitting of various styles of martial arts against each other in order to determine the dominant form. Its current practice now focuses on the dominant fighter where each fighter deploys an individually hybridized fighting technique drawing on various martial arts.1 This paper seeks to address effective aggressiveness and the treatment of aggressive behaviour in the context of MMA in comparison to the balance of the formal Canadian legal landscape. I choose anti-bullying legislation, and its treatment of aggressive behaviour, as a counterexample to the treatment of aggressive behaviour within the MMA regulatory framework. By intertextually linking and superimposing these two categories of legislation, a critical lens drawing on institutional ethnography is applied. This is done to question and deconstruct the differential treatment of aggressive behaviour and the rationale behind the legislative mixed message sent. This lens also allows me to show the importance of a more thorough analysis and understanding of the imported internal frameworks of regulated activities that are candidates for decriminalization through amendments to Canada’s Criminal Code intended to ensure the Criminal Code is current to today’s reality.2 The quandary faced within the fabric of the MMA community regarding its own treatment of aggressive * Sara Ross is a PhD student and Legal Process Instructor at Osgoode Hall Law School. -

25 Pro Fighters, Managers, and Coaches Reveal Their Best Tips to Land a Sponsorship by Solmadrid Vazquez Follow Me on Twitter Here

25 Pro Fighters, Managers, and Coaches Reveal Their Best Tips to Land a Sponsorship by Solmadrid Vazquez Follow me on Twitter here. Sponsorships can make or break you. The problem is, the process of landing a sponsorship is counter-intuitive. Being a great fighter is NOT enough. I’m sure you’ve seen fighters who land sponsors left and right. What’s their secret? How come they can get 27 sponsors in one day and you can’t even get one freakin’ rep to look at you? What THE hell is going on?! To get to this bottom of this conundrum, I contacted some of the best fighters, managers, and trainers in the game and asked them a simple question: “What is your #1 tip to land a sponsorship?” Each tip has a custom tweet link after it so feel free to share your favorite tips with your followers. Let’s Get Ready To Ruuuummmmbllllllleee!!! Frank Shamrock Frank Shamrock is a retired MMA Fighter. He was the first UFC Middleweight Champion and retired as the four-time defending undefeated champion. He was also the first WEC Light Heavyweight Champion, and the first Strikeforce Middleweight Champion. He was a brand spokesman for Strikeforce and is a Sports Commentator for Showtime. Frank can be found at his site, on Facebook, and on Twitter. My number one tip to landing a sponsorship is presenting yourself properly. Present a long-term consistent growth plan that somebody, or a sponsor, could attach themselves to, so you can show how you will grow together. “Present a long-term consistent growth plan.” Tweet this. -

MMA: Does Josh Koscheck Need to Retire?

MMA: Does Josh Koscheck need to retire? Author : Robert D. Cobb Over a brilliant career, Josh Koscheck has fought some of the biggest names in MMA history such as Tyron Woodley, Johny Hendricks, Georges St-Pierre, Diego Sanchez, Robbie Lawler and Matt Hughes. He sent Matt Hughes into retirement and handed Diego Sanchez his first professional loss. He has challenged for the UFC Welterweight championship and routinely been near the top of the card every time he fought. That is why it is so sad to see the current state of his career. With five straight losses, four of which have been early knockouts and submission defeats. His excellent wrestling skills seem to be a step slower these days, and what he had left of a chin now appears to be completely gone. As huge Josh Koscheck fan, it pains me to see this, but I have to agree with Dana White when he calls for his retirement. Koscheck has nothing left to prove. He has fought for a title, appeared on the Ultimate Fighter as both a competitor and a coach, one of the few to ever do that. He has worked his butt off and been a part of some classic fights. He entered the sport in 2004 with an excellent background in collegiate wrestling at Edinboro Univesity in PA. In 2001, during his junior season, Koscheck won all of his wrestling matches and went on to become the NCAA Division I Champion in the 174 lb weight class. In addition to being a four-time NCAA Division I All-American (placing 4th, 2nd, 1st and 3rd respectively), Koscheck is a three-time recipient of the PSAC Wrestler of the Year award and earned the Eastern Wrestling League Achievement Award twice.