'The Last of the President's Men'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baker Center Journal of Applied Public Policy - Vol

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Baker Center: Publications and Other Works Baker Center for Public Policy Fall 2012 Baker Center Journal of Applied Public Policy - Vol. IV, No.II Theodore Brown Jr. J Lee Annis Jr. Steven V. Roberts Wendy J. Schiller Jeffrey Rosen See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_bakecentpubs Part of the American Politics Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Career of Sen. Howard H. Baker, Jr. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Baker Center for Public Policy at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baker Center: Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Theodore Brown Jr., J Lee Annis Jr., Steven V. Roberts, Wendy J. Schiller, Jeffrey Rosen, James Hamilton, Rick Perlstein, David B. Cohen, Charles E. Walcott, and Keith Whittington This article is available at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange: https://trace.tennessee.edu/ utk_bakecentpubs/7 vol. 1v no. 2 BAKER CENTER JOURNAL OF BAKER CENTER JOURNAL OF APPLIED PUBLIC POLICY—SPECIAL ISSUE POLICY—SPECIAL PUBLIC APPLIED OF JOURNAL CENTER BAKER APPLIED PUBLIC POLICY Published by the Howard H. Baker Jr. Center for Public Policy at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville Howard H. Baker, Jr.: A Life in Public Service A Special Issue PREFACE AND OVERVIEW Howard H. Baker, Jr. and the Public Values of Cooperation and Civility: A Preface to the Special Issue Theodore Brown, Jr. -

Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr. During the Watergate Public Hearings

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2013 Tightrope: Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr. during the Watergate Public Hearings Christopher A. Borns Student at University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Borns, Christopher A., "Tightrope: Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr. during the Watergate Public Hearings" (2013). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1589 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tightrope: Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr. during the Watergate Public Hearings Christopher A. Borns University of Tennessee – Knoxville TIGHTROPE : SENATOR HOWARD H. BAKER , JR. DURING THE WATERGATE PUBLIC HEARINGS ABSTRACT This essay, by thoroughly analyzing Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr.’s performance as Vice-Chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities during the Watergate public hearings, examines whether Senator Baker, as the highest-ranking Republican on the committee, sought primarily to protect his own party’s President or, rather, in the spirit of bipartisanship, sought primarily to uncover the truth surrounding the Watergate affair, regardless of political implications, for the betterment of the American people. -

Senate Select Committee on the 1972 Presidential Election

UNITED STATES OF AN2~RICA CONGRESS OF TH~ UNITED STATES SUBPENA DUCES TECUM To: President Richard M. Nixon, The White House, Washington, D. C. ~ursuant to lawful authority, YOU .ARE HEREBY COMMANDED to make available to the SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN ACTIVITIES of the Senate of the United States, on Jamuary 4, 197~ o, at i0 a.m., at Room 1418 Dirksen Senate Office Building, all materials listed on Attachment A, hereto. Hereof fall not, as you will answer your default under the pains and penalties such cases made s~d . provided. TO, , .... ’,../ to serve andreturn. ’Given under my hand, by order~ ~ ~of~the Committee, this iSday .of December in the Year.of our " Lord one thousand nine hundred and Seventy?three. , ’Oh~irman, Senat~ Select Commit~tee on Presidential Campaign Activities Served on: Time: Date: Place Samuel Dash -- chief Senate counsel during Watergate heanngs rage J or ~ SFGATE HOME ¯ BUSINESS ¯ SPORTS - ENTERTAINMENT ~ TRAVEL JOBS ~ REAL I chief Senate counsel during Watergate hearings Warren E. Leafy, New York Times Sunday, May 30, 2004 Washington- Samuel Dash, a champion of legal ethics who became nationally known during the Watergate scandal as the Senate’s methodical chief counsel, died Saturday alter a long illness. He was 79. x Ernail This Article A professor at the Georgetown University Law Center for almost 40 years, he died of heart failure at the Washington Hospital Center, relatives said. Professor Dash had CONSTRUC~ON been hospitalized since January with a vadety of health problems Kitchen Remodeling/Re~cing and had a histonj of heart disease, they said. -

WATERGATE." Your Request Has Been Assigned Case Number 75372

NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY CENTRAL SECURITY SERVICE FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, MARYLAND 20755-6000 FOIA Case: 75372 23 December 2013 Mr_ John Greenewald Dear Mr. Greenewald: This responds to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request of 30 October 2013 for "Intellipedia entry (from all three Wikis. that make up the Intellipedia) for the following entry: WATERGATE." Your request has been assigned Case Number 75372. For purposes of this request and based on the information you provided in your letter, you are considered an "all other" requester. As such, you are allowed 2 hours of search and the duplication of 100 pages at no cost. Since there are no assessable fees, we have not addressed your request for a fee waiver. Please be advised that our search was conducted using the specific term you provided (i.e. Watergate), as the entry title. To the extent that you seek "all entries that include references to the [topic]", please be advised that this would prove to be an overly broad search. Two requirements must be met in order for a FOIA request to be proper: (1) the request must "reasonably" describe the records sought; and (2) it must be made in accordance with published rules stating the time, place, fees (if any), and procedures to be followed. This portion of your request does not satisfy the first requirement because agency employees familiar with the subject matter of this request cannot locate responsive records without an unreasonable amount of effort. The rationale for this rule is that FOIA was not intended to reduce Government agencies to full time investigators on behalf of requesters. -

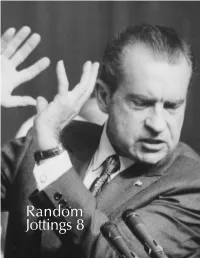

Random Jottings 8 Random Jottings 8 “Watergate Considered As an Org Chart of Semi-Precious Stones” a Fanzine by Michael Dobson

Random Jottings 8 Random Jottings 8 “Watergate Considered as an Org Chart of Semi-Precious Stones” a fanzine by Michael Dobson Michael Dobson, 8042 Park Overlook Dr., Bethesda, MD 20817, [email protected] Available for “the usual,” with PDF available from http://efanzines.com/RandomJottings/ . Copyright © 2013 by Michael Dobson under the Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution license: some rights reserved. All written material by Michael Dobson except as noted. Table of Contents Yes, This is a Fanzine (More or Less) ............................................................................ 3 Watergate and Me .......................................................................................................... 5 Origins of a Scandal ....................................................................................................... 7 The Enemies List .......................................................................................................... 11 Hunt/Liddy Special Project #1 ..................................................................................... 15 Watergate Considered as an Org Chart of Semi-Precious Stones ............................ 17 Duct and Other Tapes .................................................................................................. 37 Come Back to the Five and Dime Again, John Dean, John Dean .............................. 39 Let’s Go to the Tape, Johnny! ....................................................................................... 51 Saturday Night’s Alright (for Firing)