Spring 2016 Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Function of Mgas and Mgus a Managing General Agent (“MGA”)

12-3 MGAS, MGUS AND POOLS § 12.02[2] § 12.02 MGAs and MGUs [1]—The Function of MGAs and MGUs A managing general agent (“MGA”) is a person or (more often) an entity that manages a portion of the business of an insurance or rein- surance company. The term “managing general underwriter” (“MGU”) is often used synonymously with MGA.1 The specific functions delegated to an MGA can vary. Still, it is typical for an MGA to be charged with: (1) underwriting a specific kind of business for its principal, and (2) handling claims on that business. In addition, MGAs are often responsible for obtaining rein- surance to cover the business they write. By definition, the results of the business managed by an MGA belong to the principal. Thus, when an MGA underwrites a contract on behalf of an insurance or reinsurance company, the contract is an obligation of that company. For that reason, the MGA is said to be writing on the company’s “paper,” and to hold the company’s “pen.” Because the business handled by an MGA is really the principal’s business, the premiums and losses under that business must be reflect- ed on the company’s—not the MGA’s—financial statements. As a result, an MGA does not have the same capital requirements as an insurance or reinsurance company. The company, however, has an obvious need to make sure that the MGA is handling its responsibil- ities properly. The company also needs to receive timely and accurate reports from the MGA. There are a variety of reasons for a company to do business through an MGA. -

225-1 MANAGING GENERAL AGENTS ACT Table Of

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—October 2002 MANAGING GENERAL AGENTS ACT Table of Contents Section 1. Purpose and Scope Section 2. Definitions Section 3. Licensure Section 4. Required Contract Provisions Section 5. Duties of Insurers Section 6. Examination Authority Section 7. Penalties and Liabilities Section 8. Rules and Regulations Section 9. Effective Date Section 1. Purpose and Scope This Act may be cited as the Managing General Agents Act. This chapter governs the qualifications and procedures for resident and non-resident producers acquiring the status as a Managing General Agent. Section 2. Definitions As used in this Act: A. “Actuary” means a person who is a member in good standing of the American Academy of Actuaries. B. “Business entity” means a corporation, association, partnership, limited liability company, limited liability partnership or other legal entity. C. “Insurer” means any person duly licensed in this state as an insurance company pursuant to [insert applicable licensing statute]. D. “Managing general agent” (MGA) means any person who: (1) Manages all or part of the insurance business of an insurer (including the management of a separate division, department or underwriting office); and (2) Acts as an agent for such insurer whether known as a managing general agent, manager or other similar term, who, with or without the authority, either separately or together with affiliates, produces, directly or indirectly, and underwrites an amount of gross direct written premium equal to or more than five percent (5%) of the policyholder surplus as reported in the last annual statement of the insurer in any one quarter or year together with the following activity related to the business produced adjusts or pays claims in excess of $10,000 per claim or negotiates reinsurance on behalf of the insurer. -

Fall 2013 Surplus Lines Law Group Fall Meeting Electronic Documents State Materials in Alphabetical Order

Fall 2013 Surplus Lines Law Group Fall Meeting Electronic Documents State Materials in Alphabetical Order AK: Notice of Placement List Hearing H13-04. A hearing will be held 10/3/13 to update the surplus lines placement list. Comments are due 10/1/13. http://www.commerce.state.ak.us/insurance/Insurance/programs/notices/H13-04.pdf AK: HB146: Signed and eff. 7/1/13. Allows for proof of motor vehicle coverage to be displayed on a mobile device if from, among other things, a surplus lines broker. http://www.legis.state.ak.us/basis/get_bill_text.asp?hsid=HB0146Z&session=28 AL: Notice of 10/9/13 Hearing, including: This hearing involves the Amendment of Section 4 of Insurance Regulation No. 106 [Rule 482-1-106-.04], setting forth the rules for filing a bond by an insurer appointing a managing general agent. The proposed Amendment of Section 5 of Insurance Regulation No. 106 [Rule 482-1-106-.05], sets forth the rules for filing a copy of the audited financial statement of a managing general agent (MGA) by an insurer appointing the MGA. http://www.aldoi.gov/currentnewsitem.aspx?ID=815 AR: 2012 Annual Report of Department. It reports that there are 197 surplus lines insurers listed (134 foreign, 62 alien and one domestic – Kinsale Insurance Company). The rest of the report contains general information and financial information on companies other than surplus lines. http://insurance.arkansas.gov/index_htm_files/2012Annual.pdf AR: Bulletin 10-2013: Claims Made Policies: Notices Required. This bulletin states that it applies to insurers licensed and authorized. -

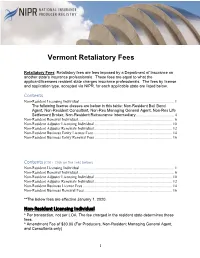

Retaliatory Fees

Vermont Retaliatory Fees Retaliatory Fees: Retaliatory fees are fees imposed by a Department of Insurance on another state's insurance professionals. These fees are equal to what the applicant/licensees resident state charges insurance professionals. The fees by license and application type, accepted via NIPR, for each applicable state are listed below. Contents Non-Resident Licensing Individual ................................................................................................ 1 The following license classes are below in this table: Non-Resident Bail Bond Agent, Non-Resident Consultant, Non-Res Managing General Agent, Non-Res Life Settlement Broker, Non-Resident Reinsurance Intermediary. ...................................... 4 Non-Resident Renewal Individual .................................................................................................. 6 Non-Resident Adjuster Licensing Individual ............................................................................... 10 Non-Resident Adjuster Renewals Individual................................................................................ 12 Non-Resident Business Entity License Fees................................................................................. 14 Non-Resident Business Entity Renewal Fees ............................................................................... 16 Contents (Ctrl + Click on the links below) Non-Resident Licensing Individual ............................................................................................... -

Insurance Agent Related Bonds by State

Insurance Agent Related Bonds By State The chart below lists the known bond requirements for insurance-related businesses. State Bond Type Amount Alabama Surplus Lines Broker $50,000 Arizona Managing General Agent Varies Arkansas Managing General Agent $100,000 Arkansas Non-Resident Insurance Broker Varies Arkansas Surplus Lines Insurance Broker/Producer $50,000 California Insurance Adjuster $2,000 California Insurance Broker $10,000 California Public Insurance Adjuster $20,000 California Special Lines' Surplus Broker $10,000 California Surplus Lines Broker $50,000 Colorado Non-Resident Insurance Broker $25,000 Colorado Public Adjuster $20,000 Delaware Public Adjuster $20,000 District Of Columbia Insurance Broker $20,000 District Of Columbia Public Insurance Adjuster $20,000 Florida Fiscal Intermediary Varies Florida Legal Expense Insurance Corporation Varies Florida Public Adjuster $50,000 Florida Surplus Lines Broker $50,000 Georgia Insurance Broker $2,500 Georgia Insurance Counselor $5,000 Georgia Non-Resident Insurance Agent $500 Georgia Public Adjuster $5,000 Georgia Surplus Lines Broker $50,000 Hawaii Public Adjuster $10,000 Idaho Insurance Consultant $10,000 Idaho Managing General Agent Varies Idaho Public Adjuster $20,000 Idaho Surplus Lines Broker $10,000 Illinois Insurance Producer/Business Entity Varies Illinois Public Adjuster / Public Adjuster Business Entity $20,000 Illinois Surplus Lines Producer's License $20,000 Indiana Insurance Agent Varies Indiana Public Adjuster $10,000 Iowa Public Adjuster $20,000 Kentucky Insurance -

Western General Insurance Company (Western General) Pursuant to Insurance Code Section

1 VERIFIED EX PARTE APPLICATION 2 Petitioner Ricardo Lara, in his capacity as Insurance Commissioner of the State of 3 California (Commissioner), hereby applies ex parte for an order appointing him Conservator of 4 Western General Insurance Company (Western General) pursuant to Insurance Code section 5 10111 and, in support of this application, respectfully alleges the following facts: 6 A. The Parties. 7 1. The Commissioner is the duly elected Insurance Commissioner of the State of 8 California. 9 2. Respondent Western General Insurance Company (Western General) is a 10 corporation duly organized and existing under and by virtue of the laws of the State of California, 11 with its principal business office located in 5230 Las Virgenes Road, Calabasas, California. 12 3. Western General is 91.8 percent owned by Western General Holding Company 13 (WGHC), a California corporation, which is in turn 51.1% owned by Mr. Robert M. Ehrlich and 14 Ms. Laurel B. Ehrlich. 15 4. Western General is a domestic insurer under section 26 and subject to examination 16 by the Commissioner pursuant to section 729 et seq. 17 5. At all relevant times, Western General is authorized to transact the business of 18 property and casualty insurance in California under a Certificate of Authority issued by the 19 Commissioner. 20 6. Western General is licensed to transact insurance in 39 states and the District of 21 Columbia. However, most of its direct premiums written is concentrated in California, with over 22 80 percent of premiums written in this state. 23 7. Western General focuses on specialty dealer-originated and agent/broker produced 24 non-standard automobile business written through its affiliated agency, All Motorists Insurance 25 Agency. -

The Increasingly Anachronistic Immunity of Managing General Agents and Independent Claims Adjusters

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2009 The "Other" Intermediaries: The Increasingly Anachronistic Immunity of Managing General Agents and Independent Claims Adjusters Jeffrey W. Stempel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Insurance Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Stempel, Jeffrey W., "The "Other" Intermediaries: The Increasingly Anachronistic Immunity of Managing General Agents and Independent Claims Adjusters" (2009). Scholarly Works. 854. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/854 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE "OTHER" INTERMEDIARIES: THE INCREASINGLY ANACHRONISTIC IMMUNITY OF MANAGING GENERAL AGENTS AND INDEPENDENT CLAIMS ADJUSTERS Jeffrey W. Stempel This article addresses the "other" intermediaries involved in the administration of insurance policies, specifically "downstream" intermediaries, who are engaged in the administration of insurance claims. The focus is on managing general agents, third-party administrators and independent contractorclaims adjusters, who perform the nuts-and-bolts tasks of the insurance industry, and are generally less well compensated than commercial insurance brokers. Since these "other" intermediariesare immune from judicial claims by policyholders, they are also less incentivized to perform their duties well. The article argues that, in order to improve the claims process, the "other" intermediaries should be held accountablefor their misconduct, at least in tort, or even for "bad faith" in the manner of an insurer. It reviews the benefits of accountability and suggests a workable standard for intermediary liability where an intermediary is potentially liable when a policyholder has alleged negligence or some greaterwrongdoing. -

Agent Liability & Kentucky

Agent Liability & Kentucky Law ©Commonwealth Schools of Insurance, Inc. P.O. Box 22414 Louisville, KY 40252-0414 Telephone: 502.425.5987 Fax: 502-429-0755 Web Site: www.commonwealthschools.com Email: [email protected] DISCLOSURE This booklet is intended to provide you with accurate and useful information, ideas and applications. However, the information contained herein is subject to change through legislation or from industry practice. The sample codes presented herein were accurate as of the date this publication was created. However, any changes by the respective organizations may substantially affect the information presented. This material is presented and distributed for educational purposes only. The material does not constitute legal, accounting, or other professional advice. ©Commonwealth Schools of Insurance, Inc. ©Commonwealth Schools of Insurance, Inc. Page 2 ERRORS & OMISSIONS Errors and omissions and professional liability insurance provides important liability protection to professionals. It covers claims for damages that are not covered by other liability forms. Through the purchase of errors and omissions insurance, the professional is protected from the risk of financial loss due to errors, acts, omissions or negligence in the rendering of professional services. The liability insurance environment is rooted in our litigation system. The agent who offers this insurance must be familiar with the legal concepts, legal terms and court decisions affecting liability insurance. The agent must also understand the elements of the insurance forms which are used to provide liability coverage. Agents offering errors and omissions and professional liability insurance provide a true service to their customers. Without this coverage, a professional is in danger of serious economic loss.