History, Naturally!" a Teacher's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Stuart Homestead Site: Historic Context Report

Thomas Stuart Homestead Historic Context Report Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Avana Andrade Public Lands History Center at Colorado State University 2/1/2012 1 Thomas Stuart Homestead Site: Historic Context Report Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge Montana is currently developing plans for a new contact station. One potential location will affect the site of a late-nineteenth-century historic homestead. Accordingly, the National Park Service and the Montana State Historic Preservation Office need more information about the historic importance of the Thomas Stuart homestead site to determine future decisions concerning the contact station. The following report provides the historic contexts within which to assess the resource’s historic significance according to National Register of Historic Places guidelines. The report examines the site’s association with Thomas Stuart, a Deer Lodge pioneer, and the Menards, a French- Canadian family, and presents the wider historical context of the fur trade, Deer Lodge’s mixed cultural milieu, and the community’s transformation into a settled, agrarian town. Though only indications of foundations and other site features remain at the homestead, the report seeks to give the most complete picture of the site’s history. Site Significance and Integrity The Thomas Stuart homestead site is evaluated according to the National Register of Historic Places, a program designed in the 1960s to provide a comprehensive listing of the United States’ significant historic properties. Listing on the National Register officially verifies a site’s importance and requires park administrators or land managers to consider the significance of the property when planning federally funded projects. -

Archives Move: Keeping Montana's Stories Alive

H A Publication of the Winter 2013 SocietyMontana Historical Society ST R Archives Move: Keeping Montana’s Stories Alive The staff of the Montana Historical Society took great care in boxing up and temporarily relocating the stories of Montana that truly are the memory of its people. It took nearly four weeks of physical labor to clear out the archives storage area in the base- ment of the Society to make room for the installation of high-density mobile shelving that will ease the In what is truly a massive change for the Montana Historical Society archives, the staff spent overcrowding MHS is experienc- nearly four weeks packing up and moving thousands of boxes of precious Montana docu- ing in all of its programs. ments to clear the way for installation of new high-density mobile storage shelving. Although the staff prides itself in making those collections avail- Photo graph Archives remain open history of the American West. It able to the public, MHS has had with limited access to collections. is used by authors, filmmakers, to restrict access to the archives To understand the scope of the researchers, and those who want until the project is complete. The project, imagine each individual to learn more about the history of thirty-five thousand linear feet of file box lined up end to end. They their own families. mate rials in the collection have would stretch out over seven The Legislature provided been moved to a secure loca- miles. $402,000 for the project, which tion off-site. It is expected that The collection is considered one will take seven months to com- the archives will open again by of the best not only on the his- plete. -

Hard Winter Endurance| Conrad Kohrs' Cattle Raising Operation, 1887-1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1996 Hard winter endurance| Conrad Kohrs' cattle raising operation, 1887-1900 Anna Fay Rosenberg The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rosenberg, Anna Fay, "Hard winter endurance| Conrad Kohrs' cattle raising operation, 1887-1900" (1996). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2509. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2509 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of ]VIONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission X No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature - Date Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Hard Winter Endurance: Conrad Kohrs' Cattle Raising Operation, 1887-1900 by Anna Fay Rosenberg presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 1996 Dean. Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP33960 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-9003 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property Historic name: Grant-Kohrs Ranch/Warren Ranch Other name/site number: Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Landmark, Grant Trading Post, John Grant Ranch, Kohrs & Bielenberg Home Ranch, Conrad Kohrs Company Ranch, CK Ranch, Warren Hereford Ranch 2. Location Street & number: Cattle Drive (no number), Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS not for publication: n/a City/town: Deer Lodge vicinity: n/a state: Montana code: MT county: Powell code: 077 zip code: 59722 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended I hereby certify that this^ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documenJaJieH-staadards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requiremgpts'setforth in 36 Ct"R Part 60. In my opinion, the property j; meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this ppfSerty be considered signifpant _ nationally X statewide __ local.y. ( _ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature~oTcertif^fig official/Title Nationll Park Service State or Federal agency or bureau In my* piniin, the property >C does not meet the National Register criteria Signati re rff comme/ffing or other official *~» 7>t-"7"£_ /-f-rf, T^c'/a-fC State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Date of Action entered in the National Register see continuation sheet determined eligible for the National Register w< ____ see continuation sheet determined not eligible for the National Register ____ see continuation sheet removed from the National Register ____ see continuation sheet other (explain) Grant-Kohrs Ranch/Warren Ranch Powell County. -

Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS: Administrative History Grant-Kohrs Ranch

Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS: Administrative History Grant-Kohrs Ranch Administrative History Ranchers to Rangers: An Administrative History of Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Douglas C. McChristian Rocky Mountain Cluster National Park Service July, 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS grko/adhi/adhi.htm Last Updated: 04-Nov-2000 file:///P|/AdminHistory/adhi/adhi.htm1/17/2007 3:20:07 PM Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS: Administrative History (Introduction) Grant-Kohrs Ranch Administrative History INTRODUCTION In the decade following World War II an expanding and prospering American public frequented its national parks as never before. It was predicted that visitation to the National Park System would double by 1960. However, by the mid-1950s most park facilities had seen no major improvements since the days of the Civilian Conservation Corps, in the 1930s, when great amounts of money and labor had been infused into the System. In the intervening years, during which the nation's attention had been dominated by World War II and the Korean War, roads, bridges, and utilities systems had deteriorated to an alarming degree. Housing for park employees was often worse, consisting of make-shift and barely habitable cabins. [1] Alarmed at the impacts of this massive influx of people, National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth proposed to Congress a ten-year program aimed at rehabilitating the system. This major overhaul of the national parks, termed the Mission 66 Program, was to be accomplished in conjunction with the 1966 fiftieth anniversary of the National Park Service. Both the Eisenhower administration and Congress endorsed Wirth's ambitious plan. In addition to the general improvement of facilities and the construction of dozens of new visitor centers, hundreds of employee houses, as well as new roads, trails, and maintenance buildings, Mission 66 also affected a dramatic expansion of the Park System. -

Illustration 1. the Granville Stuart Drawing, 6 August 1865. Courtesy

Illustration 1. The Granville Stuart drawing, 6 August 1865. Courtesy of Montana Historical Societv. 172 Illustration 2. Detail, "1883 Bird's Eye View of Deer Lodge City, County Seat of Deer Lodge Co., Montana." 176 Illustration 3. Illustration of ranch from M. A. Leeson, History of Montana, p. 556. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 180 Illustrations 4 through 15 portray some of the people associated with the Kohrs and Bielenberg home ranch. 371 Illustration 4. John F. Grant in 1866, the year he sold his ranch to Con Kohrs. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 372 Illustration 5. Conrad Kohrs, 1874. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 374 Illustration 6. Conrad Kohrs, 1882. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 376 Illustration 7. Montanans visit the home ranch of Kohrs and Bielenberg, ca. 1904. The seated figure at the far right is Con Kohrs. John Bielenberg, standing, leans against the door frame, while Otey Yancey Warren looks at a picture. Mr. Warren was Con Warren's father. The other indivi duals are unidentified. The setting is the living room of the brick addition. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 378 Illustration 8. Conrad Kohrs and John Bielenberg at the home ranch, ca. 1912. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 38 0 Illustration 9. Augusta Kohrs in 1868, age 19. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 382 Illustration 10. Augusta Kohrs in 1874, age 25. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 384 Illustration 11. Augusta Kohrs in 1882, age 33. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. 386 Illustration 12. Augusta Kohrs, about 70 years of age. Courtesy of Montana Historical Society. -

National Park Service U.S

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/GRKO/NRR—2015/1071 ON THE COVER View from the back porch of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch House, looking northwest Photograph by: Kathy Allen, SMUMN GSS Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Natural Resource Condition Assessment Natural Resource Report NPS/GRKO/NRR—2015/1071 Kathy Allen Sarah Gardner Kevin Benck Andy Nadeau Lonnie Meinke Thomas Walker Mike Komp Keaton Miles Barry Drazkowski GeoSpatial Services Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota 890 Prairie Island Road Winona, Minnesota 55987 October 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Carroll College In

THE BACKGROUND AND ORGANIZATION OF THE MONTANA STOCKGROWERS ASSOCIATION BY WILLIAM G. BERBERET A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CARROLL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR HONORS AND THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CARROLL COLLEGE HELENA, MONTANA APRIL, 1963 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA H0NT10 "V b'tfwOiiil. ____ __ -y iA9. uxvi 0 _j. o L.J4 J.0 C).ClOuX|.A SG.OQ °M.4 «^0j pOAOuddg u.OOC[ bcq +ou.u4vto^ *£) tU^vT^X^ ji.q ‘asu;^oQ *g t)4q. joj aTssqq. sfty, l<°) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................... Hi PREFACE .............. ............................. ............................. CHAPTER I, Origins and Early Settlement............................................................... ] H. Early Legislation............................................ ............................ 7 TIT. Other developments from late 6O’st o late 70*s.,,............. .. 9 IV* Early attempts at Organization...................... ................. ... • 13 V, Migration and Expansion.......... ... ........... 27 VI, The Indian Problem............... ............................. 30 VTT* The Threat of Cattle Rustlers............ ...................... 33 ’HU. Other Difficulties and Developments.......................................... 36 IX* Permanent Organization................................................................... X. Consolidation............................................ CONCLUSION................. -

Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (GRKO); Grant Trading Post; Grant Ranch; Kohrs & Bielenberg Home Ranch; CK Ranch; Warren Hereford Ranch

RECEIVED 2280 NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) Grant-Kohrs Ranch Page United Slates Department of the Interior, National PaA Service______________________ National Registei of {fefflg Places Registration Farm 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Grant-Kohrs Ranch Other Name/Site Number: Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site (GRKO); Grant Trading Post; Grant Ranch; Kohrs & Bielenberg Home Ranch; CK Ranch; Warren Hereford Ranch. 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Cattle Drive (no number), Grant-Kohrs Ranch NHS Not for publication: n/a City/Town: Deer Lodge Vicinity: n/a State: Montana Code: MT County: Powell Code: 077 Zip Code: 59722 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: X Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 18. 18 buildings 0 sites 26 structures 1 object 23 45 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPSNRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 Grant-Kohrs Ranch Page 2 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

(Nick) Bielenberg Home, Erected Between June 8Th and December 6, 1910, Is Located in the Central Addition of Deer Lodge, Lots 34, 35, 36, 37, and 38

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME ;.£„ J HISTORIC N.J. (Nick) Bielenberq Home AND/OR COMMON "The Bielenberg Home" LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 801 Milwaukee Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Deer Lodqe __ VICINITY OF 01 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE M/in !• ana P™.IO 1 1 077 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC -K&CCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM -X-BUILDING(S) _£RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS -X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Donald D. Bielenberq_____ STREET & NUMBER 801 Milwaukee Ave CITY, TOWN STATE Deer Lodge VICINITY OF Montana 59722 I LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF powe i] County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Deer Lodqe Montana 59722 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE None DATE —FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED _X>RIGINALSITE _RUINS —ALTERED _MOVED DATE- _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Nickolas John (Nick) Bielenberg home, erected between June 8th and December 6, 1910, is located in the Central Addition of Deer Lodge, Lots 34, 35, 36, 37, and 38. With few exceptions, the house being described is still in its original state. -

2015 Summer Newsletter

VOLUME 44 NEWSLETTER SUMMER 2015 The Boarding house at the Ghost Town of Emery Photo, TERRY HALDEN (See story, page 6) Montana Ghost Town The Prez Sez TERRY HALDEN Quarterly Enclosed in this newsletter is a separate sheet for those of The Montana Ghost Town Quarterly is you who are heading to our annual convention to register. Members published four times a year by the Montana Ghost Town Preservation Society, have told us to do it this way as they do not like cutting the newsletter, P.O. Box 1861, Bozeman, Montana 59771. and besides it give you a one page program that you can take to e-mail: [email protected] Great Falls. Unfortunately, as much as we pruned expenses, we still www.mtghosttown.org Copyright © 2015, all rights reserved. have to charge $75.00 per person, mainly because the cost of food has soared over the last year. However, on the bright side, there is a Founded in 1970, the Montana Ghost Town Preservation Society is a 501c3 non-profit jam packed program lined up for you. organization dedicated to educating the public to the benefits of preserving the historic buildings, Sally, who besides looking after secretary and treasurer duties sites, and artifacts that make up the living also keeps a track of our membership list. She tells me that several history of Montana. Opinions expressed in the bylined articles are of you are a little delinquent in renewing your dues, despite a couple the authors’ and do not necessarily represent of reminders in the mail. We just excommunicated one member that the views of the M. -

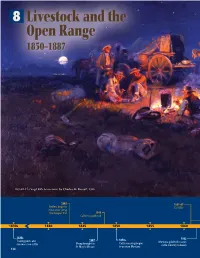

Chapter 8 Review

FIGURE 8.1: Laugh Kills Lonesome, by Charles M. Russell, 1925 1843 1861–65 Settlers begin to Civil War move west along the Oregon Trail 1848 California gold rush 1830s 1840 1845 1850 1855 1860 1830s 1862 1847 1850s Trading posts and Montana gold rush causes Sheep brought to Cattle ranching begins missions raise cattle cattle industry to boom St. Mary’s Mission in western Montana 148 READ TO FIND OUT: n What drew ranchers to Montana Territory n What problems plagued the open- range cattle ranches n How the winter of 1886–87 changed life on the open range n How the brief open-range ranching days shaped life in Montana today The Big Picture The glory days of the open range were created— and quickly brought to an end—by the same forces that drive all life in Montana: water, weather, and the land. As the bison disappeared from the Northern Plains, a new way of life spread across the Montana grasslands: the life of the cattleman on the open range. Montana offered 40 million acres of rich grazing land with some of the best grasses in the West. By pushing American Indians onto shrinking reservations, the government opened up vast regions of this public resource. Investors from all over the world came to profit from the open range. The period of open-range ranching began and ended in less than 50 years. Yet it profoundly influenced life in Montana. The days of the open range left a lasting legacy (something handed down from the past) that continues to shape life here today.