Medieval Elwick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eaglescliffe Ward ALL CHANGE!

Eaglescliffe Ward Focus www.stocktonlibdems.org.uk No 125 (Preston 101) Editors Cllr Mike Cherrett 783491 Cllr John Fletcher 786456 Cllr Maureen Rigg 782009 ALL CHANGE! This is our 125th issue for Egglescliffe Ward and our 101st for Preston, Aislaby & Newsham. Why have we combined leaflets? Next May new ward boundaries come into effect at a Stockton Council election; the new Eaglescliffe Ward will cover the combined area. At present Councillors Maureen Rigg & John Fletcher represent Egglescliffe Ward and Mike Cherrett, Preston Ward – all Liberal Democrats. From May you will have 3 councillors all serving the whole of the new ward – so, a combined leaflet for the new area. In the meantime, our councillors will continue to serve you and we shall keep you informed. Stockton Council is also progressing boundary changes to Preston-on-Tees Civil Parish, which will gain Preston Park & Preston Lane. The parish boundary currently cuts in half Preston Cemetery & a house in Railway Terrace! They will go wholly into Preston & Egglescliffe Parishes respectively. PLANNING A66 LONGNEWTON INTERCHANGE Stockton Council’s Planning Committee turned Mike was furious to hear that the long awaited down proposals to demolish The Rookery and grade-separated junction was being delayed, possi- Sunnymount and build houses & flats, following bly for 3 years. He has written to Alistair Darling, the speeches from our councillors. Transport Minister, demanding that he think again. Stockton planning officers refused conversion of Mike wrote “If you do not know the history of this Hughenden, 1 Station Road, to 3 flats & a block of 3 site and the carnage that has been caused over the more in the garden. -

At Dalton Piercy, Elwick and Hart

at Dalton Piercy, Elwick and Hart & May 2020 Produced for the Villagers by Hart and Elwick Churches Revd. Janet Burbury, The Vicarage, Hart, Hartlepool. TS27 3AP [email protected] Tel. 01429 262340 Mob 07958 131271 Dear friends, I truly wish I could wave a magic wand and comfort you all but this climate of fear and isolation is such a massive change to us all, I doubt any of us has yet to truly feel it’s implications. Be assured my prayers and pastoral support is with you. Don’t think twice before picking up the phone to contact me for a chat, to help in a practical way. I will do what I can to help. We haven’t had a ‘dispersed’ church since the days when Jesus himself walked this earth. Soon after his life on earth church buildings to gather for worship and pastoral support were built by the disciples copying the pattern of the Jewish syna- gogues of the day. Today as a dispersed church we are figuring out how to be church. If this restriction to isolate goes on, what will become of church buildings when they can’t afford their statutory upkeep including insurance, parish share and all? How will this virus refocus our society? Will the threat of this virus weaken or strengthen the Christian church? Will we become more or less community minded? As we see the empty shelves in our shops from panic buying we are certainly chal- lenged to pray more earnestly, “Give us today our daily bread”. This phrase re- minds us to ask for what we need and no more. -

23 Hartlepool to Sunderland Via Peterlee - Valid from Sunday, April 11, 2021 to Sunday, September 19, 2021

23 Hartlepool to Sunderland via Peterlee - Valid from Sunday, April 11, 2021 to Sunday, September 19, 2021 Monday to Friday - Sunderland Interchange 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 1 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 1 23 23 Marina Asda -- -- -- -- -- 0839 0909 0939 09 39 1509 1539 1609 1644 1719 1749 Hartlepool Victoria Road - Avenue Road -- -- 0659 0734 0809 0844 0914 0944 14 44 1514 1544 1614 1649 1724 1754 Hart Station Goldsmith Avenue -- -- 0711 0746 0821 0856 0926 0956 26 56 1526 1556 1626 1701 1736 1806 Blackhall Colliery Co-op Store -- -- 0719 0754 0829 0904 0934 1004 34 04 1534 1604 1634 1709 1744 1814 Horden Yoden Way -- -- 0725 0800 0835 0910 0940 1010 Then 40 10 past 1540 1610 1640 1715 1750 1820 Peterlee Bus Station 0636 0706 0736 0811 0846 0921 0951 1021 at 51 21 each 1551 1621 1656 1721 1801 1826 Easington Colliery Station Road-Office Street 0644 0714 0744 0819 0854 0929 0959 1029 these 59 29 hour 1559 1629 1704 -- 1809 -- mins until Easington Village Green 0651 0721 0751 0826 0901 0936 1006 1036 06 36 1606 1636 1711 -- 1816 -- Dalton Park Shopping Centre 0658 0728 0758 0833 0908 0943 1013 1043 13 43 1613 1643 1718 -- 1823 -- New Seaham Mill Inn - Stockton Road 0705 0735 0805 0840 0915 0950 1020 1050 20 50 1620 1650 1725 -- 1830 -- Ryhope Village The Village 0711 0741 0811 0846 0921 0956 1026 1056 26 56 1626 1656 1731 -- 1836 -- Sunderland Interchange 0720 0750 0820 0855 0930 1005 1035 1105 35 05 1635 1705 1740 -- 1845 -- 1 Term Time Only Monday to Friday - Hartlepool Victoria Road - Avenue Road 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 23 Sunderland -

Elwick Grove Brochure

Elwick Grove Hartlepool A collection of 3 and 4 bedroom homes ‘ A reputation built on solid foundations Bellway has been building exceptional the local area. Each year, Bellway commits quality new homes throughout the UK for to supporting education initiatives, providing 70 years, creating outstanding properties transport and highways improvements, in desirable locations. healthcare facilities and preserving - as well as creating - open spaces for everyone to enjoy. During this time, Bellway has earned a strong reputation for high standards of design, build Our high standards are reflected in our quality and customer service. From the dedication to customer service and we location of the site, to the design of the home believe that the process of buying and owning to the materials selected, we ensure that our a Bellway home is a pleasurable and straight impeccable attention to detail is at the forward one. Having the knowledge, support forefront of our build process. and advice from a committed Bellway team member will ensure your home-buying We create developments which foster strong experience is seamless and rewarding, communities and integrate seamlessly with at every step of the way. Welcome to Elwick Grove, a stylish master bedroom with Your dream contemporary development of en-suite bathroom, along with three and four bedroom its own garage. The design home awaits detached homes in a sought- specification inside is second to after suburb of Hartlepool. none, with chic sanitaryware and sophisticated kitchen areas. at Elwick These homes boast open plan living areas as well as front and Elwick Grove is ideally located Grove rear gardens, all of which in a rural setting, close to both provide the ideal space for the town centre and the coast, socialising with loved ones. -

15() • Eaglesoliffe.' Durham

15() • EAGLESOLIFFE.' DURHAM. [KELLY's Post, M. 0. & T. & Telephone Call Office, Eaglescliffe Wall Letter Box at .hrm station(in Egglesclifie),cleare<t .(letters should have eo. Durham added). William 8.45 a.m. & 4.20 & 6.40 p.m Stafford, sub-postmaster. Letters from Darlington Public Elementary School (mixed), for 170 children;. arrive at 5.48 a.m. & 4· 15 p.m. ; from Stock ton 5 ·45 average attendance, 109; J. R. Bouch, master a.m. & I p.m.; dispatched at 9·35 a.m. (II. 15 a. m. Railway Stations:- & 6.15 p.m. for Stockton) & 9 p.m Eaglescliffe· (N.E.R.) (junction for Hartlepool & Stock ton & Saltburn & Darlington railways), William Pillar Letter Box, Eaglescliffe, cleared 8.45 a.m. & 6-45 Stafford, station master; Frederick Dealtrey, assistant p.m.; sundays, 5.15 p.m station master; Yarm (N.E.R.) (main line from Pillar Letter Box, on the Stockton road, cleared 9 a.m. Sunderland & Leeds), John Robert Stockdale, station & 6.45 p.m.; sundays, 5.15 p.m master EA.GLESCLIFFE. Fletcher Edgar George, The Villas, Strickland Miss, Dunattar avenue Marked * receive letters via Yarm Stockton road Stuart W esley Hackworth, White (Yorks). Fletcher Miss, Highfield, Yarm road hou~, Stockton road PRIVATE RESIDENTS. Fother~ill Mrs. Torrisdale, Yarm rd Sturgess Leonard, Oakdene, Albert rd Allison Thos. Moulton ho. A.lbert rd Garthwait George Bell, Mayfield, Sutton Geo. Wm. Ashfield, Albert rd Appleton Mrs. W oodside hall Albert road Tait Misses, Albert road Asker George,Preston vil.Stockton rd Gaunt John Thomas, Eastbourne, Taylor Henry Barker, Eastleigh~ Astbury Mrs. -

Teesside Archaological Society

Recording the First World War in the Tees Valley TEESSIDE ARCHAOLOGICAL SOCIETY The following gazetteer is a list of the First World War buildings in the Tees Valley Area. Tees Archaeology has the full image archive and documentation archive. If particular sites of interest are wanted, please contact us on [email protected] 1 | P a g e Recording the First World War in the Tees Valley HER Name Location Present/Demolished Image 236 Kirkleatham Hall TS0 4QR Demolished - 260 WWI Listening Post Boulby Bank Present (Sound Mirror) NZ 75363 19113 270 Marske Hall Redcar Road, Present Marske by the Sea, TS11 6AA 2 | P a g e Recording the First World War in the Tees Valley 392 Seaplane Slipway Previously: Present Seaplane Slipway, Seaton Snook Currently: on foreshore at Hartlepool Nuclear Power Plant, Tees Road, Hartlepool TS25 2BZ NZ 53283 26736 467 Royal Flying Corps, Green Lane, Demolished - Marske Marske by the Sea (Airfield) Redcar 3 | P a g e Recording the First World War in the Tees Valley 681 Hart on the Hill Hart on the Hill, Present (Earthworks) Dalton Piercy, parish of Hart, Co. Durham TS27 3HY (approx. half a mile north of Dalton Piercy village, on the minor road from Dalton Piercy to Hart Google Maps (2017) Google Maps [online] Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/maps/place/Hart-on-the- Hill/@54.6797131,- 1.2769667,386m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x487ef3527f0a44 21:0xe4080d467b98430d!8m2!3d54.67971!4d-1.274778 4 | P a g e Recording the First World War in the Tees Valley 698 Heugh Gun Battery Heugh Battery, Present Hartlepool -

Paul's Travel ELWICK & DALTON PIERCY – HARTLEPOOL

Effective from Monday 30 April 2012 Paul’s Travel ELWICK & DALTON PIERCY – HARTLEPOOL (Tesco extra) Service 65 via High Tunstall, West Park, Ryehill Gardens, Hartlepool Centre & Hartlepool Marina Service 65 via Elwick The Green, North Lane, A19 South, The Windmill ( Ex Dalton Lodge ), Dalton Piercy Lane, Dalton Piercy Green, Dalton Piercy Lane, Hart-on-the-Hill, Dalton Crossroads, High Tunstall Elwick Road, West Park, Egerton Road, Elwick Road, Dunston Road, Hart Lane, Ryehill Gardens, Elmwood Road, Thornhill Gardens, Hart Lane, Tunstall Avenue, Hartlepool Grange Road, Victoria Road, A689 Stockton Street, A689 Marina Way, Maritime Avenue, Schooner Court, Maritime Avenue, Victoria Terrace, A178 Mainsforth Terrace, Burbank Street, Green Street, Burn Road, Tesco, Burn Road, A689 Stranton, A689 Stockton Street. Returns via A689 Stockton Street, A689 Stranton, Burn Road ( certain journeys via Tesco ), Burn Road, Green Street, Burbank Street, A178 Mainsforth Terrace, Victoria Terrace, Maritime Avenue, Schooner Court, Maritime Avenue, A689 Marina Way, A689 Stockton Street, Victoria Road, Grange Road, Tunstall Avenue, Hart Lane, Thornhill Gardens, Elmwood Road, Ryehill Gardens, Hart Lane, Dunston Road, West Park, Egerton Road, Elwick Road, High Tunstall Elwick Road, Dalton Crossroads, Elwick Road, Elwick The Green, North Lane, A19 South, The Windmill ( Ex Dalton Lodge ), Dalton Piercy Lane, Dalton Piercy Green. A “HAIL & RIDE” facility applies on this service, buses will only stop where safe to do so. Please tell the driver where you wish to alight, and hail the bus when you wish to board. MONDAY, THURSDAY, FRIDAY (No service on Bank Holidays) 65 65 65 65 65 65 Elwick Village, The Green ................................ ...................0915 1115 1315 Stockton Street, College of Further Education (Stand: R) .... -

Wildlife Guide Introduction

Heritage Coast Sunderland Durham Hartlepool Coastal wildlife guide Introduction Our coastline is a nature explorer’s dream. With dramatic views along the coastline and out across the North Sea, it has unique qualities which come from its underlying geology, its natural vegetation and the influences of the sea. It is a wonderfully varied coastline of shallow bays and headlands with yellow limestone cliffs up to 30 metres high. The coastal slopes and grasslands are home to a fabulous array of wild flowers and insects, in contrast the wooded coastal denes are a mysterious landscape of tangled trees, roe deer and woodland birds. This guide shows a small selection of some the fascinating features and wildlife you may see on your visit to our coast; from Hendon in the north to Hartlepool Headland in the south, there is always something interesting to see, whatever the time of year. Scan the code to find out more about Durham Heritage Coast. Contents 4 Birds 9 Insects 13 Marine Mammals 16 Pebbles 20 Plants 25 Sand Dunes 29 Seashore The coast is a great place to see birds. In the autumn and spring lots of different types of passage migrant birds can be seen. The UK's birds can be split in to three categories of conservation importance - red, amber and green. Red is the highest conservation priority, with species needing urgent action. Amber is the next most critical group, followed by green. The colour is shown next to the image. Please keep your dogs on a lead to avoid disturbance to ground nesting birds in the summer and also over wintering birds. -

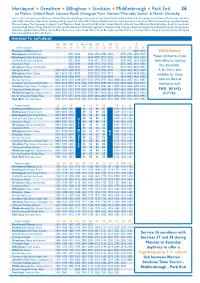

Hartlepool Greatham Billingham Stockton Middlesbrough Park End 36

Hartlepool z Greatham z Billingham z Stockton z Middlesbrough z Park End 36 via Marina, Oxford Road, Catcote Road, Owington Farm, Norton,Thornaby Station & North Ormesby Service 36 from Hartlepool Marina via Marina Way, Gateway Bridge,Victoria Road,York Road, Stockton Road, Oxford Road, Catcote Road, Owton Manor Lane, Stockton Road A689, Greatham High Street, Greatham Bridge, Stockton Road A689, Newton Bewley, Stockton Road, Seal Sands Link Road, Marsh House Avenue, Rievaulx Avenue, Melrose Avenue,The Causeway, Roseberry Road,Wolviston Road, Station Road, Billingham Green,West Road, South View, Billingham Bank, Billingham Road, Norton Road, Stockton High Street, Bridge Road,Victoria Bridge, Mandale Road, Middlesbrough Road, Stockton Road, Newport Road, Hartington Road, Brentnall Street, Grange Road, Middlesbrough Bus Station,Wilson Street,Albert Road, Corporation Road, Marton Road, Borough Road,West Terrace, Cromwell Street, King's Road, Ormesby Road, Ingram Road, Crossfell Road, Overdale Road.. MONDAY TO SATURDAY NS NS NS S NS + NS NS S NS S + E Service number 36A 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 Hartlepool Marina, Asda ------------0801 0816 DDA Aware Hartlepool, Victoria Road - - 0623 0628 - 0646 0703 0708 0720 - 0738 0753 0803 0819 Hartlepool, York Road Library - - 0625 0630 - 0648 0705 0710 0722 - 0740 0755 0806 0822 Please contact us if you Oxford Road, Catcote Road - - 0631 0636 - 0654 0711 0716 0728 - 0746 0801 0812 0828 have difficulty reading Rossmere Hotel - - 0635 0640 - 0658 0715 0720 0732 - 0750 0805 0816 0832 this -

Fishmonger 1911

Fishmonger 1911 This group, with 21 household in the 1911 census, is descended from Elizabeth Kipling, via her sons Lionel and James. Elizabeth was most likely the daughter of Joseph and Mary Kipling (see “Staindrop 1911”). Lionel and some of his descendants were fishmongers in Bishop Auckland in the 19th century. James and his family were shipbuilders, moving to West Hartlepool, Whitby and, in the 20th century, to Birkenhead. Elizabeth ,---------- ---------------- ---------------- -----|----- ------------ -----¬ Joseph Lionel James dsp? | see later ,---------- ------,------ ---------------- -----|----- ------,------ ------------ -----¬ Samuel Joseph =Jane Anne Lionel John Henry Nathanael = Margaret Ewbank #42 dsmp #28 #37 #35 dsmp #36 #384 | `-------- ---------------------¬ |------- ------,------ ------,-----------¬ |------- ---------------- ------,------ ------,-------------¬ | George Thomas May Rowena John William Lionel Samuel Edward | William #155 #113 Willink #169 #62 dsp dsp | ? #350 |--------------¬ |------- ------,-----------¬ |------- ------,------ ------,------ ------,-----------¬ James John Samuel Henry John Joseph Jonathan Harold Adam Robert | William #32 #18 William dsp #33 Lionel Bertie Joseph | dsp | ? ? #90 ? |--------------¬ |--------------¬ John Adelina William Jack Casmere Theodora #82 #274 Baptisms, Teesdale District - Record Number: 711777.0 Location: Barnard Castle Church: St. Mary Denomination: Anglican 22 Sep 1805 Joseph Kipling of Bishop Auckland, born 3 Mar, illegitimate son of Elizabeth Kipling (single woman, -

Egglescliffe Conservation Area Appraisal

Chapter CO5: Egglescliffe Conservation Area Appraisal Egglescliffe Conservation Area Page EG1 Plan of Egglescliffe Conservation Area showing listed buildings and areas covered by Article 4 Directions Egglescliffe Conservation Area Page EG2 General Overview of Egglescliffe Conservation Area. Egglescliffe Village is tucked away from many people down a ‘dead end’, and most are unfamiliar with its chocolate-box central green. This has been one of its greatest assets in recent times as it has largely escaped damaging modernisation and redevelopment, leaving behind an intact Georgian village. Egglescliffe is supposed to derive its name from Ecclesia Church-on-the- Cliffe, or, as it has been interpreted by those who claim an earlier origin, Church-by-the-Flood, being Celtic. Whatever the origin of the name, it must not be confused with the more recent development called Eaglescliffe. Historians believe that Egglescliffe was first established some time in the 11th Century as it was mentioned in the Domesday book, which makes it one of the oldest settlements in Teesside. The village layout is typical of many North Yorkshire rural communities where houses and shops were arranged around a central green space, and lesser buildings including farms located on the periphery. Egglescliffe 1895 It is likely that the site was chosen for its defensive position atop a rocky outcrop on a meander of the River Tees, which also happens to be the lowest crossing point at low tide. Over the years the trees on the green have matured and provide an attractive environment which, together with the pleasant buildings and the location tucked away from main roads, creates one of the most pleasant villages in the North East. -

Hartlepool Walking and Cycling Map Here

O S N A QUEEN'SQU R R D O O A A D D RO B AD 1 D 2 ROAOA UEEN'S'S 8 FILLPOKE LANE Q 0 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R WingW ate MOOR LANE To Sunderland MonkMonk and Peterlee For more information on cycling and walking in the area go to COAST ROADROA F R HesledenHe O N www.letsgoteesvalley.co.uk Places of interestT Tees Valley S To Crimdon & T R E Blackhall Rocks ET Crimdonimdoono Beck Nor Crimd NesbitNesNe t md th Ward Jackson Park K5 Sa A B1B DeneDene Ha on Beck Scale 1:20,000 128 r nds 0 t to K S T H A a Burn Valley Gardens L6 T s B IO Hartlepool w N el 0 Miles 12 R l W 1 O al 1 ADA D kwa Rossmere Park L8 2 HARTLEPOOL A C y 1 0 B1280 SSeeatoneaeaatontononn CarewCCareCaCara ew 8 DURHAMM 6 0 Kilometres 123 Seaton Park O8 D Thee C O MIM CommonCommmmommon A I S L F W E B T IN B EL R L GA OWSW R © Crown Copyright and database right 2018. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100015871. TETE R A N S BU D O Summerhill Country Park K6 StationStation D R O AD N N L A E A Redcar Central AN A L L E K BILLINGHAM D E E Bellows Burn T Redcar East C ToTowwnn C E Golf Course L R L CemeteryCemetery Billingham D E R OA A ET HutHutton E R O Art Gallery / Tourist Information Centre M5 RE ILL C F C T V E S T E T Longbeck AR V A N H E N HenryHenry R O R BEB N R F Marske ELLLLOWSW O S BURURN E Saltburn LANE R A D W South Bank R IN A D G A St.