THE NATION the Idea of Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/02/2021 06:27:32AM Via Free Access 117

116 7 WHITE VULNERABILITY AND THE POLITICS OF REPRODUCTION IN TOP OF THE LAKE: CHINA GIRL JohannA gondouin, surucHi ThApAr-BjörKert And ingrid ryberg op of The Lake: China Girl (Australia, Jane Campion, 2017) is the sequel to Jane Campion and Gerard Lee’s crime series Top of the Lake from T2013, directed by Campion and Ariel Kleiman. After four years of absence, Inspector Robin Griffin (Elisabeth Moss) returns to the Sydney Police Force and comes to lead the murder case of an unidentified young Asian woman, found in a suitcase at Bondi Beach. The investigation connects Robin to a group of Thai sex workers, and a network of couples – including two of her closest colleagues – willing to pay these women large sums of money as surrogate mothers via illegal commercial arrangements. Moreover, on her return to Sydney, Robin makes contact with her now teenage daughter Mary (Alice Englert), whom she gave up for adoption at a young age. Worrying links between the murdered girl and Mary are revealed, as it turns out that one of the prime suspects is Mary’s boyfriend Puss (David Dencik). The circumstances surrounding the adoption are revealed in season one, set in the fictional town of Laketop, New Zealand. Visiting her dying mother, Robin becomes involved in the investigation of the disappearance of a preg- nant twelve- year- old, Tui. The case results in the exposure of a paedophile ring implicating a large number of men in the small community, among others the missing girl’s father and the police officer in charge. In the pro- cess, Robin’s traumatic past unfolds through flashbacks: the gang rape that she was the victim of as a teenager, and the following pregnancy and adoption. -

Selected Academic Bibliography Career Overviews

Updated: August 2015 Sally Potter: Selected Academic Bibliography Career Overviews: Books The second, longer annotation for each of these books is quoted from: Lucy BOLTON, “Catherine Fowler, Sally Potter and Sophie Mayer, The Cinema of Sally Potter” [review] Screen 51:3 (2010), pp. 285-289. Please cite any quotation from Bolton’s review appropriately. Catherine FOWLER, Sally Potter (Contemporary Film Directors series). Chicago: University of Illinois, 2009. Fowler’s book offers an extended and detailed reading of Potter’s early performance work and Expanded Cinema events, staking a bold claim for reading the later features through the lens of the Expanded Cinema project, with its emphasis on performativity, liveness, and the deconstruction of classical asymmetric and gendered relations both on-screen and between screen and audience. Fowler offers both a career overview and a sustained close reading of individual films with particular awareness of camera movement, space, and performance as they shape the narrative opportunities that Potter newly imagines for her female characters. “By entitling the section on Potter’s evolution as a ‘Search for a “frame of her own”’, Fowler situates the director firmly in a feminist tradition. For Fowler, Potter’s films explore the tension for women between creativity and company, and Potter’s onscreen observers become ‘surrogate Sallys’ in this regard (p. 25). Fowler describes how Potter’s films engage with theory and criticism, as she deconstructs and troubles the gaze with her ‘ambivalent camera’ (p. 28), the movement of which is ‘designed to make seeing difficult’ (p. 193). For Fowler, Potter’s films have at their heart the desire to free women from the narrative conventions of patriarchal cinema, having an editing style and mise- en-scene that never objectifies or fetishizes women; rather, Fowler argues, Potter’s women are free to explore female friendships and different power relationships, uncoupled, as it were, from narratives that prescribe heterosexual union. -

Being a Woman in the 1950S and the 1960S: Women and Everyday Life in Ginger and Rosa

Journalism and Mass Communication, Mar.-Apr. 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, 102-116 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2020.02.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING Being a Woman in the 1950s and the 1960s: Women and Everyday Life in Ginger and Rosa Ezgi Sertalp Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey The present study aims to focus on the relationship between gender and everyday life and reflect on the meanings of being a woman in the 1950s and the 1960s over Sally Potter’s film Ginger and Rosa (2012a). The 1950s and the 1960s are marked with significant changes and transformations in terms of the social statuses and everyday lives of women in many countries all around the world. Women began to question their gendered roles and performances, resist “doing gender” and speak out “the problem that has no name” in these years, which would then evolve into the second-wave feminist movement—a significant historical period in women’s history. Therefore, an analysis of this specific period is considered significant to understand the relationship between gender and everyday life. Thus, the present study first addresses the relationship between gender and everyday life in general terms, discussing the social construction of gender and how we are taught to do gender through socialization. Then, it examines women’s practices, performances, relationships, conflicts, and resistances in their everyday lives throughout the 1950s and the 1960s over the film Ginger and Rosa. Considering the historical, social, and political developments at the time, this study tries to explore significant issues within feminist studies such as the relationship between mothers and daughters, and female friendship/sisterhood through the characters in the film, and comprehend what it meant to be a young girl, a woman, a wife, and a mother in both private and public spheres in these years based upon the director’s own experiences and memories. -

Moma Sally Potter

MoMA CELEBRATES FOUR-DECADE CAREER OF SALLY POTTER WITH A TWO- WEEK RETROSPECTIVE OF HER DIVERSE, INDEPENDENT FILMS Exhibition Includes the Premiere of Potter’s Digitally Remastered Film, Orlando (1992), and Her Most Recent Feature, RAGE (2009) Sally Potter July 7–21, 2010 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, June 8, 2010—A retrospective of the films of British director Sally Potter (b. 1949) at The Museum of Modern Art from July 7 through 21, 2010, celebrates her distinct, independent vision, showing all her feature films, documentaries, and shorts, and a selection of her experimental works made between the early 1970s and the present. Potter has consistently kept a radical edge in her filmmaking work, beginning with avant-garde short films and moving on to alternative dramatic features that embrace music, literature, dance, theater, and performance. Potter typically works on multiple elements of her films, from script and direction to sound design, editing, performance, and production. Her films elegantly blend poetry and politics, giving voice to women’s stories and romantic liaisons and exploring themes of desire and passion, self- expression, and the role of the individual in society. Considered together in this retrospective, Potter’s films reveal the common thread of transformation that runs through her work—in terms both of her characters’ journeys and her own ability to transcend genre and work with cutting- edge film forms. Sally Potter is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art. The opening night, Wednesday, July 7, at 8:00 p.m., is the U.S. -

A Film by Sally Potter

Official Selection Toronto International Film Festival Telluride Film Festival Mongrel Media presents YES A film by Sally Potter with Joan Allen, Simon Abkarian, Sam Neill and Shirley Henderson (UK/USA, 95 minutes) Distribution 1028 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] High res stills may be downloaded from http://mongrelmedia.com/press.html CONTENTS MAIN CREDITS 3 SHORT SYNOPSIS 4 LONG SYNOPSIS 4-5 SALLY POTTER ON YES 6-10 SALLY POTTER ON THE CAST 11 ABOUT THE CREW 12-14 ABOUT THE MUSIC 15 CAST BIOGRAPHIES 16-18 CREW BIOGRAPHIES 19-21 DIRECTOR’S BIOGRAPHY 22 PRODUCERS’ BIOGRAPHIES 23 GREENESTREET FILMS 24-25 THE UK FILM COUNCIL 26 END CREDITS 27-31 2 GREENESTREET FILMS AND UK FILM COUNCIL PRESENT AN ADVENTURE PICTURES PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH STUDIO FIERBERG A FILM BY SALLY POTTER Y E S Written and directed by SALLY POTTER Produced by CHRISTOPHER SHEPPARD ANDREW FIERBERG Executive Producers JOHN PENOTTI PAUL TRIJBITS FISHER STEVENS CEDRIC JEANSON JOAN ALLEN SIMON ABKARIAN SAM NEILL SHIRLEY HENDERSON SHEILA HANCOCK SAMANTHA BOND STEPHANIE LEONIDAS GARY LEWIS WIL JOHNSON RAYMOND WARING Director of Photography ALEXEI RODIONOV Editor DANIEL GODDARD Production Design CARLOS CONTI Costume Design JACQUELINE DURRAN Sound JEAN-PAUL MUGEL VINCENT TULLI Casting IRENE LAMB Line Producer NICK LAWS 3 SHORT SYNOPSIS YES is the story of a passionate love affair between an American woman (Joan Allen) and a Middle-Eastern man (Simon Abkarian) in which they confront some of the greatest conflicts of our generation – religious, political, and sexual. -

Ginger & Rosa DIRECCIÓN: Sally Potter FOTOGRAFÍA

FICHA TÉCNICA Ginger Rosa TÍTULO ORIGINAL: Ginger & Rosa DIRECCIÓN: Sally Potter PRODUCTORA: Adventure Pictures GUIÓN: Sally Potter MÚSICA: Amy Ashworth FOTOGRAFÍA: Robbie Ryan PAÍS: Reino Unido AÑO: 2012 GÉNERO: Drama DURACIÓN: 90 minutos IDIOMA: inglés PROTAGONISTAS: Elle Fanning, Alice Englert, Christina Hendricks, Annette Bening, Alessandro Nivola,Oliver Platt, Jodhi May, Oliver Milburn, Andrew Hawley PREMIOS: 2012: Festival de Valladolid - Seminci: Mejor actriz (Fanning) (ex-aequo) 2012: British Independent Film Awards (BIFA): Nom. Mejor actriz (Fanning) y sec. (Englert) 2012: Critics Choice Awards: Nominada mejor intérprete joven (Fanning) SINOPSIS: Londres, 1962. Ginger y Rosa son dos adolescentes y amigas inseparables. Juntas hacen hablan de amor, religión y política; sueñan con una vida más emocionante que la doméstica existencia de sus madres. Pero la creciente amenaza de la guerra nuclear proyecta una sombra sobre su futuro. Ginger se siente atraída por la poesía y por la protesta política, mientras que Rosa le enseña a Ginger a fumar, a besar a los chicos y a rezar. Las dos se rebelan contra sus respectivas madres. 1 Federación Mexicana de Universitarias Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Museo de la Mujer Bolivia 17 Centro Histórico, Ciudad de México. Cine-Club de género 4 de septiembre de 2018 Mtra. Delia Selene de Dios Vallejo♣♥ Ginger & Rosa está ambientada durante la Guerra Fría y, por lo tanto, en el constante temor de una bomba nuclear; en la película se muestran dos familias las cuales se unen por coincidencias políticas y sociales estas familias conviven hasta crear vínculos inquebrantables entre ellas. Ginger y Rosa son las respectivas hijas de estas dos familias, cuyos lazos sobrepasan la amistad para convertirse en cómplices. -

Into the Forest

INTO THE FOREST WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Patricia Rozema BASED ON THE NOVEL BY Jean Hegland a BRON STUDIOS and RHOMBUS MEDIA production in association with DAS FILMS, SELAVY, VIE ENTERTAINMENT and CW MEDIA FINANCE STARRING Ellen Page Evan Rachel Wood Max Minghella Callum Keith Rennie Wendy Crewson 101 MINUTES PR Contacts US Sara Serlen, ID PR E: [email protected] / P: 212.774.6148 / C: 917-239.0829 Canada Dana Fields, TARO PR E: [email protected] / P: 416.930.1075 / C: 416.930.1075 SYNOPSIS In the not-too-distant future, two ambitious young women, Nell and Eva, live with their father in a lovely but run-down home up in the mountains somewhere on the West Coast. Suddenly the power goes out; no one knows why. No electricity, no gasoline. Their solar power system isn’t working. Over the following days, the radio reports a thousand theories: technical breakdowns, terrorism, disease and uncontrolled violence across the continent. Then, one day, the radio stops broadcasting. Absolute silence. Step by ominous step, everything that Nell, a would-be academic, and Eva, a hard working contemporary dancer, have come to rely on is stripped away: parental protection, information, food, safety, friends, lovers, music -- all gone. They are faced with a world where rumor is the only guide, trust is a scarce commodity, gas is king and loneliness is excruciating. To battle starvation, invasion and despair, Nell and Eva fall deeper into a primitive life that tests their endurance and bond. Ultimately, the sisters must work together to survive and learn to discover what the earth will provide. -

Feminist Phenomenology and the Films of Sally Potter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-prints Repository Chapter 11 Feminist Phenomenology and the Films of Sally Potter Kate Ince 1 Sally Potter’s place in British cinema is uncontested, as a recent retrospective organised by the British Film Institute shows.1 Since her debut with the half-hour Thriller in 1979, she has carved out a place for herself as one of our leading independent filmmakers, but success has often not come easily: the highly crafted experimentalism of Thriller met with acclaim, but her similarly styled first feature The Gold Diggers (1983) failed to find much appreciation, and she struggled for nine years to be able to complete Orlando (1992), her adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s 1928 Orlando: A Biography.2 With Orlando Potter was carried by the spirit of the shift in women’s filmmaking from experimentalism and explicitly political reflection on representation towards narrative pleasure, while still giving an undeniably feminist twist to Woolf’s story of time-travel and gender-bending from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries. The feminist political drive that had marked all her films up to 1992 was maintained by Potter’s own performance in the allegory of gender relations built into her next film The Tango Lesson (1997), but has been much less evident subsequently, in The Man Who Cried (2000) and Yes (2005). Other kinds of politics have marked Potter’s filmmaking in the 2000s, although in her most recent production Rage (2009), anti-capitalism might be said to be just as evident as in The Gold Diggers. -

From Paragone to Symbiosis. Sensations of In-Betweenness In

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 17 (2019) 23–44 DOI: 10.2478/ausfm-2019-0013 From Paragone to Symbiosis. Sensations of In-Betweenness in Sally Potter’s The Tango Lesson Judit Pieldner Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania (Cluj-Napoca, Romania) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Sally Potter’s The Tango Lesson (1997), an homage to the Argentine tango, situated in-between autobiography and fiction, creates multiple passages between art and life, the corporeal and the spiritual, emotional involvement and professional detachment. The romance story of filmmaker Sally Potter and dancer Pablo Verón is also readable as an allegory of interart relations, a dialogue of the gaze and the image, a process evolving from paragone to symbiosis. Relying on the strategies of dancefilm elaborated by Erin Brannigan (2011), the paper examines the intermedial relationship between film and dance in their cine-choreographic entanglement. Across scenes overflowing with passion, the film’s haptic imagery is reinforced by the black-and-white photographic image and culminates in a tableau moment that foregrounds the manifold sensations of in-betweenness and feeling of “otherness” that the protagonists experience, caught in-between languages, cultures, and arts.1 Keywords: Sally Potter, dancefilm, intermediality, cine-choreography, tableau vivant, in-betweenness. Interpretive Approaches to Sally Potter’s The Tango Lesson The Tango Lesson (1997), a highly personal declaration of love to dance and film allows a glimpse at both sides of the camera by employing the filmmaker Sally as the protagonist, a fictitious counterpart of the real-life Sally Potter. The film starts with Sally caught in the middle of a creative crisis in her London home as she is working on the scenes of a film project entitledRage . -

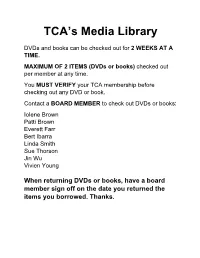

TCA's Media Library

TCA’s Media Library DVDs and books can be checked out for 2 WEEKS AT A TIME. MAXIMUM OF 2 ITEMS (DVDs or books) checked out per member at any time. You MUST VERIFY your TCA membership before checking out any DVD or book. Contact a BOARD MEMBER to check out DVDs or books: Iolene Brown Patti Brown Everett Farr Bert Ibarra Linda Smith Sue Thorson Jin Wu Vivien Young When returning DVDs or books, have a board member sign off on the date you returned the items you borrowed. Thanks. Tango Club of Albuquerque Video Rentals – Complete List V1 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 1 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The first tape covers the basics including the proper embrace and elementary steps. The video quality is high and so is the instruction. The voice over is a bit dramatic and sometimes slightly out of synch with the steps. The tapes are a somewhat expensive for the amount of material covered, but this is a good series for anyone just starting in Tango. V2 - El Tango Argentino - Vol 2 Eduardo and Gloria A famous dancing and teaching couple have developed a series of tapes designed to take a dancer from neophyte to accomplished intermediate in salon-style Tango. (This is not the club-style Tango Eduardo sometimes teaches in workshops.) The second and third videos cover additional steps including complex figures and embellishments. -

News Release

News Release Friday 12 April 2019 National Portrait Gallery Unveils Newly Commissioned Portraits of Leading Film Directors Portraits of Amma Asante, Paul Greengrass, Asif Kapadia, Ken Loach, Sam Mendes, Nick Park, Sally Potter, Sir Ridley Scott and Joe Wright go on display for first time Images clockwise from top left: (29:04:37) Ridley Scott by Nina Mae Fowler, 2018-19; (39:44:02) Sam Mendes by Nina Mae Fowler, 2018-19; (01:44:48) Sally Potter by Nina Mae Fowler, 2018-19; (00:21:22) Joe Wright by Nina Mae Fowler, 2018-19. All works © National Portrait Gallery. Photographed by Douglas Atfield The National Portrait Gallery, London, has unveiled a major new commission of portrait drawings of some of the UK’s leading film directors by London-born artist Nina Mae Fowler. The portraits have gone on public display for the first time in a new display Luminary Drawings: Portraits of Film Directors by Nina Mae Fowler (12 April – 1 October 2019). Fowler’s work often investigates fame, desire and our relationship with cinema. For the commission, she invited directors Amma Asante, Paul Greengrass, Asif Kapadia, Ken Loach, Sam Mendes, Nick Park, Sally Potter, Sir Ridley Scott and Joe Wright to choose a film of particular significance to them. During the sittings, Fowler projected the film of their choice, and recorded their reactions on camera and through loose sketches, with their faces lit only by the light of the screen in an otherwise darkened space. Images L-R: (20:30:17) Ken Loach by Nina Mae Fowler, 2018-19; (01:40:25) Amma Asante by Nina Mae Fowler, 2018-19. -

The Guardian Interview

8/12/2015 Sally Potter: 'I dreamed about the nuclear threat most nights' | Film | The Guardian Sally Potter: 'I dreamed about the nuclear threat most nights' Ginger & Rosa, which charts the friendship of two teenage girls in postwar London, draws on the film-maker's own memories of the Cuban missile crisis Catherine Shoard Thursday 4 October 2012 20.30 BST ou would never call Sally Potter a ginge. Not just because you wouldn't dare. Or Y because it would be like squirting ketchup over a slice of Poilane, or programming a double bill of The Tango Lesson and StreetDance 2 3D. You wouldn't even risk "strawberry blonde". The famed Potter mane is a big mingle of lemon and silver and cinnamon, which shimmers, Titian-ish. Yet there is little doubt that she is, in some sense, Ginger, the carrot-topped hero of her new film. Ginger & Rosa is about baby-boomer best buddies, born on the same day, whose friendship in postwar London comes under strain when Rosa (Alice Englert) starts shagging Ginger's glamorous academic dad (Alessandro Nivola), freshly separated from her housewife mum (Christina Hendricks, doing downtrodden). The plot might not be autobiography, but Ginger's activist roots, social conscience, poetic heart, and parts of that barnet, are all Potter. "Every story to some degree has to draw on personal experience," she says. "Magpie-like, you scavenge, and then you transform until it is its own world. But I did grow up during the Cuban missile crisis. I was on Aldermaston marches from the age of 10, I was very, very aware of the nuclear threat and I grew up in a leftwing, outsider, academic milieu.