Attention and Implicit Memory: Priming-Induced Benefits and Costs Have Distinct Attentional Requirements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implicit Memory in Amnesic Patients: When Is Auditory Priming Spared?

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (1995), 1, 434-442. Copyright © 1995 INS. Published by Cambridge University Press. Printed in the USA. Implicit memory in amnesic patients: When is auditory priming spared? DANIEL L. SCHACTER1 AND BARBARA CHURCH2 1 Harvard University and Memory Disorders Research Center, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Cambridge, MA 02138 2 University of Illinois, Champaign, IL 61820 (RECEIVED February 16, 1995; ACCEPTED March 2, 1995) Abstract Amnesic patients often exhibit spared priming effects on implicit memory tests despite poor explicit memory. In previous research, we found normal auditory priming in amnesic patients on a task in which the magnitude of priming in control subjects was independent of whether speaker's voice was same or different at study and test, and found impaired voice-specific priming on a task in which priming in control subjects is higher when speaker's voice is the same at study and test than when it is different. The present experiments provide further evidence of spared auditory priming in amnesia, demonstrate that normal priming effects are not an artifact of low levels of baseline performance, and provide suggestive evidence that amnesic patients can exhibit voice-specific priming when experimental conditions do not require them to interactively bind together word and voice information. (JINS, 1995, 7, 434-442.) Keywords: Amnesia, Priming, Implicit memory Introduction jects heard a list of spoken words and judged either the category to which each word belongs (semantic encoding It is well known that amnesic patients can exhibit robust task) or the pitch of the speaker's voice (nonsemantic en- implicit memory despite impaired explicit memory. -

Discovery Misattribution: When Solving Is Confused with Remembering

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association 2007, Vol. 136, No. 4, 577–592 0096-3445/07/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.577 Discovery Misattribution: When Solving Is Confused With Remembering Sonya Dougal Jonathan W. Schooler New York University University of British Columbia This study explored the discovery misattribution hypothesis, which posits that the experience of solving an insight problem can be confused with recognition. In Experiment 1, solutions to successfully solved anagrams were more likely to be judged as old on a recognition test than were solutions to unsolved anagrams regardless of whether they had been studied. Experiment 2 demonstrated that anagram solving can increase the proportion of “old” judgments relative to words presented outright. Experiment 3 revealed that under certain conditions, solving anagrams influences the proportion of “old” judgments to unrelated items immediately following the solved item. In Experiment 4, the effect of solving was reduced by the introduction of a delay between solving the anagrams and the recognition judgments. Finally, Experiments 5 and 6 demonstrated that anagram solving leads to an illusion of recollection. Keywords: recognition, memory misattribution, recollection, insight problem There is something very similar about the experience of recol- found that increasing the perceptual fluency of items on a recog- lection and that of discovery. In both cases, a thought comes to nition test by preceding them with subliminally -

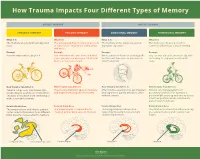

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders. Shannon Buckles Sebastian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sebastian, Shannon Buckles, "Explicit Memory Bias for Body-Related Stimuli in Eating Disorders." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5826. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5826 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Perceptual Thresholds and Priming in Amnesia

Neuropsychology In the public domain 1995, Vol. 9, No. 1,3-15 Perceptual Thresholds and Priming in Amnesia Stephan B. Hamann Larry R. Squire University of California, San Diego Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Diego and University of California, San Diego Daniel L. Schacter Harvard University The widely accepted idea that perceptual priming is intact in amnesia was challenged recently by the suggestion that perceptual identification (PID) thresholds are elevated in amnesia and that this impairment could mask a priming deficit by artificially inflating priming scores. The authors examined the PID thresholds of amnesic patients across a wide range of stimulus conditions and accuracy levels. Baseline thresholds and priming effects were fully intact for all amnesic patients except in a condition using small stimuli (1.1° x 0.25° of visual angle). In that condition, only the patients with Korsakoff's syndrome were impaired. Accordingly, elevated perceptual thresholds are not a necessary consequence of amnesia, and normal priming in amnesia is not an artifact of threshold differences. The results support the conclusion that priming is independent of the brain structures important for declarative memory that are damaged in amnesia. Considerable evidence has accumulated in recent years for medial temporal lobe and diencephalic structures that are distinguishing between different kinds of memory that depend damaged in amnesia (Squire & Zola-Morgan, 1991; Zola- on multiple separate brain systems (Richardson-Klavehn & Morgan & Squire, 1993). Nondeclarative memory is indepen- Bjork, 1988; Schacter, 1987; Squire, 1982; Tulving, 1985; dent of these brain structures. Weiskrantz, 1990). The major distinction is between declara- The conclusion that nondeclarative memory is spared in tive (explicit) memory, which affords conscious recollection of amnesia is based on a considerable body of evidence compar- past facts or episodes, and nondeclarative (implicit) memory, ing normal and memory-impaired subjects. -

Neuropsychologia Repetition Priming in Amnesia

1HXURSV\FKRORJLD[[[ [[[[ [[[²[[[ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neuropsychologia journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuropsychologia Repetition priming in amnesia: Distinguishing associative learning at different levels of abstraction Elizabeth Racea,b,⁎, Keely Burkeb, Mieke Verfaellieb a Department of Psychology, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02150, United States b Memory Disorders Research Center, VA Boston Healthcare System and Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02130, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Learned associations between stimuli and responses make important contributions to priming. The current study Repetition priming aimed to determine whether medial temporal lobe (MTL) binding mechanisms mediate this learning. Prior Hippocampus studies implicating the MTL in stimulus-response (S-R) learning have not isolated associative learning at the Memory response level from associative learning at other levels of representation (e.g., task sets or decisions). The current S-R binding study investigated whether the MTL is specifically involved in associative learning at the response level by testing a group of amnesic patients with MTL damage on a priming paradigm that isolates associative learning at the response level. Patients demonstrated intact priming when associative learning was isolated to the stimulus- response level. In contrast, their priming was reduced when associations between stimuli and more abstract representations (e.g., stimulus-task or stimulus-decision associations) could contribute to performance. These results provide novel neuropsychological evidence that S-R contributions to priming can be supported by regions outside the MTL, and suggest that the MTL may play a critical role in linking stimuli to more abstract tasks or decisions during priming. 1. Introduction et al., 2014) or “event files” (Hommel, 1998). -

Priming and the Brain Review

Neuron, Vol. 20, 185±195, February, 1998, Copyright 1998 by Cell Press Priming and the Brain Review Daniel L. Schacter*§ and Randy L. Buckner²³ minutes to several hours, subjects are given three-letter *Department of Psychology word stems with multiple possible completions and are Harvard University asked to complete each stem with the first word that Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 comes to mind (e.g., mot___ for the target word ªmotelº). ² Department of Psychology Priming occurs when subjects complete the stem with Washington University a designated target completion more often for words St. Louis, Missouri 63130 that had been studied earlier than for words that were ³ MGH-NMR Center not studied previously. In a related kind of experiment, Charlestown, Massachusetts 02129 subjects study a list of words and are later given a word identification test, where words are flashed briefly (e.g., Introduction for 35 ms) and subjects attempt to identify them. Priming occurs when subjects identify more previously studied Research in cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, words than nonstudied words. Similar kinds of tasks and neuroscience has converged recently on the idea have been developed for examining priming of numer- that memory is composed of dissociable forms and sys- ous different types of stimuli, including pseudowords tems (Squire, 1992; Roediger and McDermott, 1993; (Keane et al., 1995; Bowers, 1996), familiar and unfa- Schacter and Tulving, 1994; Willingham, 1997). This con- miliar objects (Biederman and Cooper, 1991; Srinivas, clusion has been based on experimental and theoretical 1993; Schacter et al., 1993b), visual patterns (Musen analyses of a variety of different phenomena of learning and Squire, 1992), and environmental sounds (Chiu and and memory. -

Effect of the Time-Of-Day of Training on Explicit Memory

Time-of-dayBrazilian Journal of training of Medical and memory and Biological Research (2008) 41: 477-481 477 ISSN 0100-879X Effect of the time-of-day of training on explicit memory F.F. Barbosa and F.S. Albuquerque Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil Correspondence to: F.F. Barbosa, Departamento de Fisiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, Caixa Postal 1511, 59072-970 Natal, RN, Brasil Fax: +55-84-211-9206. E-mail: [email protected] Studies have shown a time-of-day of training effect on long-term explicit memory with a greater effect being shown in the afternoon than in the morning. However, these studies did not control the chronotype variable. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if the time-of-day effect on explicit memory would continue if this variable were controlled, in addition to identifying the occurrence of a possible synchronic effect. A total of 68 undergraduates were classified as morning, intermediate, or afternoon types. The subjects listened to a list of 10 words during the training phase and immediately performed a recognition task, a procedure which they repeated twice. One week later, they underwent an unannounced recognition test. The target list and the distractor words were the same in all series. The subjects were allocated to two groups according to acquisition time: a morning group (N = 32), and an afternoon group (N = 36). One week later, some of the subjects in each of these groups were subjected to a test in the morning (N = 35) or in the afternoon (N = 33). -

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W

2.33 Implicit Memory and Priming W. D. Stevens, G. S. Wig, and D. L. Schacter, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ª 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 2.33.1 Introduction 623 2.33.2 Influences of Explicit Versus Implicit Memory 624 2.33.3 Top-Down Attentional Effects on Priming 626 2.33.3.1 Priming: Automatic/Independent of Attention? 626 2.33.3.2 Priming: Modulated by Attention 627 2.33.3.3 Neural Mechanisms of Top-Down Attentional Modulation 629 2.33.4 Specificity of Priming 630 2.33.4.1 Stimulus Specificity 630 2.33.4.2 Associative Specificity 632 2.33.4.3 Response Specificity 632 2.33.5 Priming-Related Increases in Neural Activation 634 2.33.5.1 Negative Priming 634 2.33.5.2 Familiar Versus Unfamiliar Stimuli 635 2.33.5.3 Sensitivity Versus Bias 636 2.33.6 Correlations between Behavioral and Neural Priming 637 2.33.7 Summary and Conclusions 640 References 641 2.33.1 Introduction stimulus that result from a previous encounter with the same or a related stimulus. Priming refers to an improvement or change in the When considering the link between behavioral identification, production, or classification of a stim- and neural priming, it is important to acknowledge ulus as a result of a prior encounter with the same or that functional neuroimaging relies on a number of a related stimulus (Tulving and Schacter, 1990). underlying assumptions. First, changes in informa- Cognitive and neuropsychological evidence indi- tion processing result in changes in neural activity cates that priming reflects the operation of implicit within brain regions subserving these processing or nonconscious processes that can be dissociated operations. -

Semantic Priming in Schizophrenia: a Review and Synthesis

Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (2002), 8, 699–720. Copyright © 2002 INS. Published by Cambridge University Press. Printed in the USA. DOI: 10.1017.S1355617702801357 CRITICAL REVIEW Semantic priming in schizophrenia: A review and synthesis MICHAEL J. MINZENBERG,1 BETH A. OBER,2 and SOPHIA VINOGRADOV1 1Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco and Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California 2Department of Human and Community Development, University of California, Davis and Department of Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care System, Martinez, California (Received October 9, 2000; Revised June 4, 2001; Accepted June 5, 2001) Abstract In this paper, we present a review of semantic priming experiments in schizophrenia. Semantic priming paradigms show utility in assessing the role of deficits in semantic memory network access in the pathology of schizophrenia. The studies are placed in the context of current models of information processing. In this review we include all English-language reports (from peer-reviewed journals) of single-word semantic priming studies involving participants with schizophrenia. The studies to date show schizophrenic patients to exhibit variable semantic priming effects under automatic processing conditions, and consistent impairments under controlled0attentional conditions. We also describe associations with other neurocognitive dysfunction, neurochemical and electrophysiological disturbances, and clinical manifestations (such as thought disorder). (JINS, 2002, 8, 699–720.) Keywords: Semantic priming, Schizophrenia, Semantic memory, Language, Information processing INTRODUCTION Semantic Memory and Spreading Schizophrenia is primarily a disorder of thinking and lan- Activation Network Models guage. Indeed, investigators have suggested that a defect in All information processing models posit the existence of a language information processing may be pathognomonic of long-term memory system. -

Introduction to "Implicit Memory: Multiple Perspectives"

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 1990. 28 (4). 338-340 Introduction to "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives" DANIEL L. SCHACTER University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona Psychological studies of memory have traditionally assessed retention of recently acquired in formation with recall and recognition tests that require intentional recollection or explicit memory for a study episode. During the past decade, there has been a growing interest in the experimen tal study of implicit memory: unintentional retrieval of information on tests that do not require any conscious recollection of a specific previous experience. Dissociations between explicit and implicit memory have been established, but theoretical interpretation ofthem remains controver sial. The present set of papers examines implicit memory from multiple perspectives-cognitive, developmental, psychophysiological, and neuropsychological-and addresses key methodological, empirical, and theoretical issues in this rapidly growing sector of memory research. The papers that follow were presented at a symposium Delaney, 1990; Tulving & Schacter, 1990), it is also pos entitled "Implicit memory: Multiple perspectives," held sible to adopt a unitary or single-system view of memory at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society in At and still make use of the implicit/explicit distinction (e.g., lantaonNovember 17,1989. The symposium represents Roediger, Weldon, & Challis, 1989; Witherspoon & something of a milestone, in the sense that if someone Moscovitch, 1989). had suggested organizing an implicit memory symposium The distinction between implicit and explicit memory a decade ago, he or she probably would have been met is also closely related to the distinction between "direct" with a blank stare. That stare would have reflected two and "indirect" tests of memory (Johnson & Hasher, important facts: first, because the term "implicit 1987). -

Implicit Memory: How It Works and Why We Need It

Implicit Memory: How It Works and Why We Need It David W. L. Wu1 1University of British Columbia Correspondence to: [email protected] ABSTRACT Since the discovery that amnesiacs retained certain forms of unconscious learning and memory, implicit memory research has grown immensely over the past several decades. This review discusses two of the most intriguing questions in implicit memory research: how we think it works and why it is important to human behaviour. Using priming as an example, this paper surveys how historic behavioural studies have revealed how implicit memory differs from explicit memory. More recent neuroimaging studies are also discussed. These studies explore the neural correlate of priming and have led to the formation of the sharpening, fatigue, and facilitation neural models of priming. The latter part of this review discusses why humans have evolved with highly flexible explicit memory systems while still retaining inflexible implicit memory systems. Traditionally, researchers have regarded the competitive interaction between implicit and explicit memory systems to be fundamental for essential behaviours like habit learning. However, recently documented collaborative interactions suggest that both implicit and explicit processes are potentially necessary for optimal memory and learning performance. The literature reviewed in this paper reveals how implicit memory research has and continues to challenge our understanding of learning, memory, and the brain systems that underlie them. Keywords: implicit memory, priming, neural priming, habit learning INTRODUCTION several days despite having no recollection of the learning trials. For a time it was Not until Scoville and Milner believed that the acquisition of motor studied the amnesic patient H.M.