Lars Peter Hansen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960’

JOURNALOF Monetary ECONOMICS ELSEVIER Journal of Monetary Economics 34 (I 994) 5- 16 Review of Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s ‘A monetary history of the United States, 1867-1960’ Robert E. Lucas, Jr. Department qf Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA (Received October 1993; final version received December 1993) Key words: Monetary history; Monetary policy JEL classijcation: E5; B22 A contribution to monetary economics reviewed again after 30 years - quite an occasion! Keynes’s General Theory has certainly had reappraisals on many anniversaries, and perhaps Patinkin’s Money, Interest and Prices. I cannot think of any others. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s A Monetary History qf the United States has become a classic. People are even beginning to quote from it out of context in support of views entirely different from any advanced in the book, echoing the compliment - if that is what it is - so often paid to Keynes. Why do people still read and cite A Monetary History? One reason, certainly, is its beautiful time series on the money supply and its components, extended back to 1867, painstakingly documented and conveniently presented. Such a gift to the profession merits a long life, perhaps even immortality. But I think it is clear that A Monetary History is much more than a collection of useful time series. The book played an important - perhaps even decisive - role in the 1960s’ debates over stabilization policy between Keynesians and monetarists. It organ- ized nearly a century of U.S. macroeconomic evidence in a way that has had great influence on subsequent statistical and theoretical research. -

Three US Economists Win Nobel for Work on Asset Prices 14 October 2013, by Karl Ritter

Three US economists win Nobel for work on asset prices 14 October 2013, by Karl Ritter information that investors can't outperform markets in the short term. This was a breakthrough that helped popularize index funds, which invest in broad market categories instead of trying to pick individual winners. Two decades later, Shiller reached a separate conclusion: That over the long run, markets can often be irrational, subject to booms and busts and the whims of human behavior. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted that the two men's findings "might seem both surprising and contradictory." Hansen developed a statistical method to test theories of asset pricing. In this Monday, June 15, 2009, file photo, Rober Shiller, a professor of economics at Yale, participates in a panel discussion at Time Warner's headquarters in New York. The three economists shared the $1.2 million prize, Americans Shiller, Eugene Fama and Lars Peter Hansen the last of this year's Nobel awards to be have won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic announced. Sciences, Monday, Oct. 14, 2013. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File) "Their methods have shaped subsequent research in the field and their findings have been highly influential both academically and practically," the academy said. Three American professors won the Nobel prize for economics Monday for shedding light on how Monday morning, Hansen said he received a phone stock, bond and house prices move over time— call from Sweden while on his way to the gym. He work that's changed how people around the world said he wasn't sure how he'll celebrate but said he invest. -

![Myron S. Scholes [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5900/myron-s-scholes-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-daniel-b-395900.webp)

Myron S. Scholes [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B

Myron S. Scholes [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 590-593 Abstract Myron S. Scholes is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/766/ScholesIPEL.pdf ECON JOURNAL WATCH Schelling, Thomas C. 2007. Strategies of Commitment and Other Essays. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Schelling, Thomas C. 2013. Email correspondence with Daniel Klein, June 12. Schelling, Thomas C., and Morton H. Halperin. 1961. Strategy and Arms Control. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund. Myron S. Scholes by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Myron Scholes (1941–) was born and raised in Ontario. His father, born in New York City, was a teacher in Rochester. He moved to Ontario to practice dentistry in 1930. Scholes’s mother moved as a young girl to Ontario from Russia and its pogroms (Scholes 2009a, 235). His mother and his uncle ran a successful chain of department stores. Scholes’s “first exposure to agency and contracting problems” was a family dispute that left his mother out of much of the business (Scholes 2009a, 235). In high school, he “enjoyed puzzles and financial issues,” succeeded in mathematics, physics, and biology, and subsequently was solicited to enter a engineering program by McMaster University (Scholes 2009a, 236-237). -

The Past, Present, and Future of Economics: a Celebration of the 125-Year Anniversary of the JPE and of Chicago Economics

The Past, Present, and Future of Economics: A Celebration of the 125-Year Anniversary of the JPE and of Chicago Economics Introduction John List Chairperson, Department of Economics Harald Uhlig Head Editor, Journal of Political Economy The Journal of Political Economy is celebrating its 125th anniversary this year. For that occasion, we decided to do something special for the JPE and for Chicago economics. We invited our senior colleagues at the de- partment and several at Booth to contribute to this collection of essays. We asked them to contribute around 5 pages of final printed pages plus ref- erences, providing their own and possibly unique perspective on the var- ious fields that we cover. There was not much in terms of instructions. On purpose, this special section is intended as a kaleidoscope, as a colorful assembly of views and perspectives, with the authors each bringing their own perspective and personality to bear. Each was given a topic according to his or her spe- cialty as a starting point, though quite a few chose to deviate from that, and that was welcome. Some chose to collaborate, whereas others did not. While not intended to be as encompassing as, say, a handbook chapter, we asked our colleagues that it would be good to point to a few key papers published in the JPE as a way of celebrating the influence of this journal in their field. It was suggested that we assemble the 200 most-cited papers published in the JPE as a guide and divvy them up across the contribu- tors, and so we did (with all the appropriate caveats). -

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

THE EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Economics By Nora Alhamdan 2014 SIGNATURE PAGE THESIS: The Efficient Market Hypothesis AUTHOR: Nora Alhamdan DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2014 Economics Department Dr. Carsten Lange _________________________________________ Thesis Committee Chair Economics Dr. Bruce Brown _________________________________________ Economics Dr. Craig Kerr _________________________________________ Economics ii ABSTRACT The paper attempts testing the random walk hypothesis, which the strong form of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. The theory suggests that stocks prices at any time “fully reflect” all available information (Fama, 1970). So, the price of a stock is a random walk (Enders, 2012). iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .............................................................................................................. ii Abstract ......................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ................................................................................................................ vi List of Figures ............................................................................................................... vii Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 History ......................................................................................................................... -

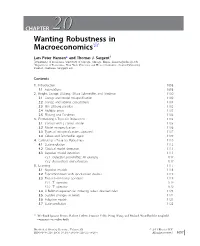

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

Editor's Letter

Why I Shall Miss Merton Miller Peter L. Bernstein erton Miller’s death received the proper somewhere,” he recalls. Miller was instrumental in tak- notices due a winner of the Nobel Prize, but ing Sharpe to the Quadrangle Club in Chicago, where Mthese reports emphasize the importance of he could present his ideas to faculty members like his intellectual contributions rather than his significance Miller, Lorie, and Fama. The invitation led to an as a human being. Nobody gives out Nobel Prizes for appointment to join the Chicago faculty, and Sharpe being a superior member of the human race, but Miller and his theories were on their way. would surely have been a laureate if someone had ever Miller’s role in launching the Black-Scholes- decided to create such a prize. Merton option pricing model was even more deter- Quite aside from the extraordinary insights gained mining. In October 1970, the three young scholars from Modigliani-Miller, we owe Merton Miller a deep had completed their work, and began the search for a debt of gratitude for his efforts to promote the careers journal that would publish it. “A Theoretical Valuation of young scholars whose little-noted innovations would Formula for Options, Warrants, and Other in time rock the world of finance. Works at the core of Securities”—subsequently given the more palatable modern investment theory might still be gathering dust title of “The Pricing of Options and Corporate somewhere—or might not even have been created— Liabilities”—was promptly rejected by Chicago’s by guest on October 1, 2021. -

Letter in Le Monde

Letter in Le Monde Some of us ‐ laureates of the Nobel Prize in economics ‐ have been cited by French presidential candidates, most notably by Marine le Pen and her staff, in support of their presidential program with regards to Europe. This letter’s signatories hold a variety of views on complex issues such as monetary unions and stimulus spending. But they converge on condemning such manipulation of economic thinking in the French presidential campaign. 1) The European construction is central not only to peace on the continent, but also to the member states’ economic progress and political power in the global environment. 2) The developments proposed in the Europhobe platforms not only would destabilize France, but also would undermine cooperation among European countries, which plays a key role in ensuring economic and political stability in Europe. 3) Isolationism, protectionism, and beggar‐thy‐neighbor policies are dangerous ways of trying to restore growth. They call for retaliatory measures and trade wars. In the end, they will be bad both for France and for its trading partners. 4) When they are well integrated into the labor force, migrants can constitute an economic opportunity for the host country. Around the world, some of the countries that have been most successful economically have been built with migrants. 5) There is a huge difference between choosing not to join the euro in the first place and leaving it once in. 6) There needs to be a renewed commitment to social justice, maintaining and extending equality and social protection, consistent with France’s longstanding values of liberty, equality, and fraternity. -

Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change∗

Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change∗ Michael Barnett William Brock Lars Peter Hansen Arizona State University University of Wisconsin University of Chicago and University of Missouri January 30, 2020 Abstract Geophysicists examine and document the repercussions for the earth’s climate induced by alternative emission scenarios and model specifications. Using simplified approximations, they produce tractable characterizations of the associated uncer- tainty. Meanwhile, economists write highly stylized damage functions to speculate about how climate change alters macroeconomic and growth opportunities. How can we assess both climate and emissions impacts, as well as uncertainty in the broadest sense, in social decision-making? We provide a framework for answering this ques- tion by embracing recent decision theory and tools from asset pricing, and we apply this structure with its interacting components to a revealing quantitative illustration. (JEL D81, E61, G12, G18, Q51, Q54) ∗We thank James Franke, Elisabeth Moyer, and Michael Stein of RDCEP for the help they have given us on this paper. Comments, suggestions and encouragement from Harrison Hong and Jose Scheinkman are most appreciated. We gratefully acknowledge Diana Petrova and Grace Tsiang for their assistance in preparing this manuscript, Erik Chavez for his comments, and Jiaming Wang, John Wilson, Han Xu, and especially Jieyao Wang for computational assistance. More extensive results and python scripts are avail- able at http://github.com/lphansen/Climate. The Financial support for this project was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation [grant G-2018-11113] and computational support was provided by the Research Computing Center at the University of Chicago. Send correspondence to Lars Peter Hansen, University of Chicago, 1126 E. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) of William Sharpe (1964)

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 18, Number 3—Summer 2004—Pages 25–46 The Capital Asset Pricing Model: Theory and Evidence Eugene F. Fama and Kenneth R. French he capital asset pricing model (CAPM) of William Sharpe (1964) and John Lintner (1965) marks the birth of asset pricing theory (resulting in a T Nobel Prize for Sharpe in 1990). Four decades later, the CAPM is still widely used in applications, such as estimating the cost of capital for firms and evaluating the performance of managed portfolios. It is the centerpiece of MBA investment courses. Indeed, it is often the only asset pricing model taught in these courses.1 The attraction of the CAPM is that it offers powerful and intuitively pleasing predictions about how to measure risk and the relation between expected return and risk. Unfortunately, the empirical record of the model is poor—poor enough to invalidate the way it is used in applications. The CAPM’s empirical problems may reflect theoretical failings, the result of many simplifying assumptions. But they may also be caused by difficulties in implementing valid tests of the model. For example, the CAPM says that the risk of a stock should be measured relative to a compre- hensive “market portfolio” that in principle can include not just traded financial assets, but also consumer durables, real estate and human capital. Even if we take a narrow view of the model and limit its purview to traded financial assets, is it 1 Although every asset pricing model is a capital asset pricing model, the finance profession reserves the acronym CAPM for the specific model of Sharpe (1964), Lintner (1965) and Black (1972) discussed here. -

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography

Τεύχος 53, Οκτώβριος-Δεκέμβριος 2019 | Issue 53, October-December 2019 ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη Nobel Prize in Economics Τα τεύχη δημοσιεύονται στον ιστοχώρο της All issues are published online at the Bank’s website Τράπεζας: address: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/trapeza/kepoe https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the- t/h-vivliothhkh-ths-tte/e-ekdoseis-kai- bank/culture/library/e-publications-and- anakoinwseis announcements Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. Κέντρο Πολιτισμού, Bank of Greece. Centre for Culture, Research and Έρευνας και Τεκμηρίωσης, Τμήμα Documentation, Library Section Βιβλιοθήκης Ελ. Βενιζέλου 21, 102 50 Αθήνα, 21 El. Venizelos Ave., 102 50 Athens, [email protected] Τηλ. 210-3202446, [email protected], Tel. +30-210-3202446, 3202396, 3203129 3202396, 3203129 Βιβλιογραφία, τεύχος 53, Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019, Bibliography, issue 53, Oct.-Dec. 2019, Nobel Prize Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη in Economics Συντελεστές: Α. Ναδάλη, Ε. Σεμερτζάκη, Γ. Contributors: A. Nadali, E. Semertzaki, G. Tsouri Τσούρη Βιβλιογραφία, αρ.53 (Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019), Βραβείο Nobel στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη 1 Bibliography, no. 53, (Oct.-Dec. 2019), Nobel Prize in Economics Πίνακας περιεχομένων Εισαγωγή / Introduction 6 2019: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer 7 Μονογραφίες / Monographs ................................................................................................... 7 Δοκίμια Εργασίας / Working papers ......................................................................................