FWU Journal of Social Sciences, Summer 2020, Vol.14, No.2, 61-80

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rising Phoenix

Community Community A new Popular Arab artificial singer Kadim P6intelligence P16 al-Saher all set tool could possibly to perform on August use data to prevent 16-17 at Qatar National sepsis in hospital Convention Centre patiences. (QNCC). Monday, August 12, 2019 Dhul-Hijja 11, 1440 AH Doha today: 320 - 420 The rising phoenix Bilal Ashraf, talks about picking up the roles to take Pakistan film industry a step forward. P4-5 2 GULF TIMES Monday, August 12, 2019 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.43am Shorooq (sunrise) 5.07am Zuhr (noon) 11.40am Asr (afternoon) 3.09pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.13pm Isha (night) 7.43pm USEFUL NUMBERS The Angry Birds Movie 2 planning to use an elaborate weapon to destroy the fowl and DIRECTION: Thurop Van Orman swine way of life. After picking their best and brightest, the CAST: Jason Sudeikis, Josh Gad, Leslie Jones birds and pigs come up with a scheme to infi ltrate the island, SYNOPSIS: Red, Chuck, Bomb and the rest of their deactivate the device and return to their respective paradises feathered friends are surprised when a green pig suggests that intact. Emergency 999 they put aside their diff erences and unite to fi ght a common Worldwide Emergency Number 112 threat. Aggressive birds from an island covered in ice are THEATRES: Landmark, Royal Plaza, The Mall Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 -

2. Ordering the Social World a Sociolinguistic Analysis of Gender

FWU Journal of Social Sciences, Winter 2015, Vol.9, No.2, 14-21 Ordering the Social World: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Gender Roles In Pakhtun Folk Wisdom Qaisar Khan and Arab Naz University of Malakand, Chakdara Dir Lower, KPK Uzma Anjum National University of Modern Languages (NUML), Islamabad Faisal Khan Center for Management and Commerce, University of Swat Gender roles and division of labor have been exhaustively researched in the recent decades. Many studies address gender bias and disparity and strive for striking a balance between the roles of men and women. This paper argues that roles are culturally conditioned and based on cultural relativism, Pakhtun society segregate masculine and feminine domains for peaceful co-existence. Guided by the theoretical perspective of Herbert Mead (1901-1978) division of labor is not always discriminatory or biased and its existence can be justified in particular settings. The findings of the study are based on qualitative linguistic analysis of collated folk tappas (plural of tappa) from archived (and/or) published collections and their authors’ interpretations. The study intends to investigate and highlight gender role segregation as projected in the language of tappas with a view to establish their relevance to social order in the long history of Pakhtuns residing on Pak-Afghan border in the north-west frontier province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The findings of the study conclude that gender roles fit into the patriarchal social structure of Pakhtuns and define social roles and responsibilities for peaceful co-existence of the two genders. Keywords: language; cultural relativism; Pakhtun; gender; Pakhtunwali The argument of the study is based on the anthropological perspective of cultural conditioning which emphasizes the role of culture in shaping attitudes, behaviors, social practices and above all gender roles to maintain division of labor. -

This Paper Focuses on Gender Disparity Behind the Camera, As Seen in Film Industries Worldwide, with a Focus on Contemporary Pakistani Cinema

This paper focuses on gender disparity behind the camera, as seen in film industries worldwide, with a focus on contemporary Pakistani cinema. Not only is there an obvious lack of gender parity in on-screen film representations, but this disproportionality increases when one looks at the gender of individuals behind the lens. Directors, writers, producers, editors, cinematographers, and composers are just a few of the people who must work y behind the scenes to bring a story to life on the big screen. As in many other industries, women are underrepresented in filmmaking while systemic biases in the film industry inhibit the inclusion of women within all technological departments. This study addresses this inequality by exploring local socioeconomic factors and questions the repercussions of this imbalance on the final screen texts. There has been no previous in- depth analysis of this issue within the Pakistani film industry, hence statistical models are presented using data from mainstream digital films released from 2013 to 2018. This analysis also relies on interviews of individuals currently working in the industry with the goal of including first- Keywords: Gender Disparity, Film Production, Pakistani Cinema, Pakistani Digital Cinema, Female Directors The dominant discourse on gender and film tends to focus on the representation of women on-screen: the unequal power dynamics, the hyper-sexualized objectification, the excessive use of the male gaze, and a conspicuous lack of main-stream female stories. Increasingly though the conversation has started to shift towards issues previously overlooked, including the widening pay gap, misogynistic discrimination and sexual harassment which have led to the emergence of charged global movements such as Me Too and assault in the workplace and more specifically in the film industry. -

Senior Taliban Commander Killed in Samangan

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:XI Issue No:19 Price: Afs.15 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimes www.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes THURSDAY.AUGUST 11. 2016 -Asad 21, 1395 HS Atmar off to Dushanbe for talks on security cooperation AT Monitoring Desk KABUL: National Security Advi- sor Mohammad Hanif Atmar on Wednesday left for Dushanbe on a day-long official visit for talks with his Tajik counterpart. A statement from the Nation- al Security Council said Atmar was AT Monitoring Desk visiting the Central Asian country KABUL: Hundreds of Taliban in- at the invitation of Tajik Security surgents launched vast attacks on Council Secretary Abdurahim Qah- the Janikhel district of eastern Pa- horov. ktia province, where heavy clash- The advisor is due to meet KABUL: A former lawmaker and ly implemented was the creation es underway between Afghan se- Tajikistan’s President Emomali prominent Pakistani politician of military courts. Reforms in sem- curity forces and the Taliban in- Rahmon on subjects of common Afrasiab Khattak said that Paki- inaries, disallowing proscribed or- surgents, provincial official said interest, including security coop- stani security establishment’s sup- ganizations to function under new Wednesday. eration and the fight against ter- port for the Afghan Taliban is an names, mainstreaming the tribal “The clashes are ongoing two rorism. open secret. areas, and taking action against kilometers from the center of Jan- Atmar would also convey He is not the only one, as sev- militants in [the eastern province ikhel. If supporting troops are not President Ashraf Ghani’s greetings eral other politicians and critics of] Punjab were never implement- sent into the district as soon as to Rahmon, the statement added. -

6 Militants Killed in Kandahar

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:XI Issue No:41 Price: Afs.20 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes WEDNESDAY . SEPTEMBER 06. 2017 -Sunbula 15, 1396 HS AT Monitoring Desk of e-NIC has been completed, should have started earlier, but its adding the authority would issue work process has followed KABUL: The Biometric Identity e-NIC as per time table. political issues,” said MP, Ghulam Cards Issuing Authority (BICIA) “The e-ID cards roll out is Hussain Nasiri. has said on Tuesday that timetable going to be launched very soon and “I believe it is still more of for distribution of the electronic the Presidential Palace, Chief slogan and I am not much National Identity Cards (e-NIC) Executive Office and other optimistic in regard,” he added. Qarabagh residents said foreign troops helicopters to be specified next week. relevant organizations are On the other hand, some bombed an engagement party on Monday night, The announcement comes at a supporting the process,” said Wais people believe the issue of e-NIC time when the government has Payab, Deputy Head of BICIA. must not be politicized in a bid to killing two people and wounding three others. already directed the BICIA to start However, some Afghan halt the process. issuing electronic identity cards Parliamentarians (MPs) have not “It is national process which within 90 days. been seen optimistic about the e- has effective outcomes and ensures According to BICIA, 90 NIC roll out process. transparency of the elections,” said percent of process for distribution “The distribution process a Kabul resident, Asadullah. -

Pashtoon Culture in Pashto Tappa

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com1 For evaluation only. PASHTOON CULTURE IN PASHTO TAPPA Dr. Hanif Khalil NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL & CULTURAL RESEARCH QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com2 For evaluation only. TO TARIQ RAHMAN (Ph.D) THE EMERITUS PROFESSOR Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com3 For evaluation only. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT INTRODUCTION Chapter No: 1 Pashtoon Culture in the perspective of Pashto Folk Poetry Chapter No: 2 Pashtoon Culture and Tappa 1. Pashto Tappa (historical and Cultural perspective) 2. Status of Women and Tappa Chapter No: 3 Social Life 1. Norms and Traditions in perspective of kinship Relations 2. Hospitality (Hujra and Milmastiya) 3. Romance (Goodar) 4. Jewelry, Dress and Music Chapter No: 3 Economical Life Chapter No: 4 Religious Life Chapter No: 5 Wars and Resistance Chapter No: 6 Tribal Life and Regional Tappas Chapter No: 7 Journeys Chapter No: 8 Conclusion Appendix References Biblography Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com4 For evaluation only. ACKNOWLEDGMENT I cordially thank Profesor Dr. Khurram Qadir, the Director National Institte of Historical and Cultural Research (NIHCR), Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, who has given to me a research project titled "Pashtoon Culture in Pashto Tappa" and supported me on every step during the fulfillment of this research work. Dear friend and a young scholar of English and Pashto Literature Mr. Ishfaq Ullah also helped me in providing research material and other relevant documentation. Special thanks are due to both of them with the core of my heart. -

33°C—42°C Today D

Community Community Birdwatchers Blind and flock to Malta, visually P7the only EU P16 impaired country allowing football fans in wild bird hunting, Germany can still enjoy to watch out matches thanks to for rule breakers. tailored commentaries. Friday, June 22, 2018 Shawwal 8, 1439 AH DOHA 33°C—42°C TODAY PUZZLES 12 & 13 LIFESTYLE/HOROSCOPE 14 COVER Does Ramadan end with Eid? Not quite. A doctor’s STORY prescription for a healthy and rewarding life. P2-3 2 GULF TIMES Friday, June 22, 2018 COMMUNITY COVER STORY On the good trail post-Ramadan PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.15am Ramadan has come to a close for another year, but that Shorooq (sunrise) 4.44am Zuhr (noon) 11.36am Asr (afternoon) 2.58pm doesn’t mean we have to leave everything behind. It’s time Maghreb (sunset) 6.58pm Isha (night) 7.58pm for us to become proactive on how we are going to maintain USEFUL NUMBERS the ‘Ramadan lifestyle’, suggests Dr Sakir Thurempurath Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Water Corporation 44845555, 44845464 Primary Health Care Corporation 44593333 44593363 Qatar Assistive Technology Centre 44594050 Qatar News Agency 44450205 44450333 Q-Post – General Postal Corporation 44464444 Humanitarian Services Offi ce (Single window facility for the repatriation of bodies) Ministry of Interior 40253371, 40253372, 40253369 Ministry of Health 40253370, 40253364 Hamad Medical Corporation 40253368, 40253365 Qatar Airways 40253374 ote Unquo Qu te Yesterday is not ours to recover, but tomorrow is ours to very year, the holy month of Ramadan has come to a close for win or lose. -

Final Version EC

Wesleyan ♦ University Global Cultural Flows and the Post-9/11 Secularization of Sufi Music of Pakistan By Muhammad Usman Malik Faculty Advisor: Dr. Eric Charry A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Middletown, Connecticut May 2015 Abstract Global Cultural Flows and the Post-9/11 Secularization of Sufi Music of Pakistan explores the development of Sufi music of Pakistan since the events of September 11, 2001. It involves the association of Sufi music with contemporary social concepts and issues, the rise of non-ritual Sufi compositions and non-hereditary Sufi musicians to popularity, and the increasing presence of Sufi music on social media and regional film and TV. I call these transformations the secularization of Sufi music of Pakistan. I demonstrate that the secularization is happening due to disjunctive global flows of ideas, money, and media. I present four case studies to substantiate this claim. The first concerns Punjabi Sufi musician Sain Zahoor’s unusual movement from obscurity to stardom. This change is driven in part by certain US policy initiatives to modernize the Islamic world to address Muslim violence against the West. The second, Zahoor’s composition “Allah hoo” (God is) from the Pakistani film Khuda Ke Liye, concerns how this new transformation of Sufi music is constructing a liberal Islamic perspective in the context of global Muslim feminism. The third examines the transformation of jugni, a popular Punjabi genre, into a Sufi genre, attributing it to the multinational Coca Cola corporation’s attempts to construct a multicultural Pakistani identity. -

The Social Perspective of Pashto Tapa

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD ISSN: 2455-0620 Volume - 6, Issue - 8, Aug – 2020 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal with IC Value: 86.87 Impact Factor: 6.719 Received Date: 30/07/2020 Acceptance Date: 16/08/2020 Publication Date: 31/08/2020 The social perspective of Pashto Tapa Azizurahman Haqyar Assistant Professor, Pashto Department, Faryab University, Maymana, Afghanistan Email – [email protected], Abstract: Tappa is a literary genre of Pashto language. It is the oldest and most popular form of Pashto folk literature. It is Tapa which has remained the most useful source of expression of sentiments of Pashtuns especially female folk. Tapa has given place to many subject i. e social, religious, romantic, political, cultural etc. Folk songs reflect the every internal feelings, emotions and sentiments of a particular area or locality therefore its universality and emotional effects cannot be ignored. These songs keep honesty, sincerity and truthfulness. Tapa or Landay is the oldest and most popular form of Pashto Literature having significance role in Pashto Folklore literature. Pashto Tapa is the mirror of Pashtun society, civilization and culture, reflects its every way of living. No such example is available in any nation’s history. Tapa or Landay consisted of one and half lines and each Tapa is called an essay as a whole. Tapa also narrates precise essay and each subject of a Tapa is presented as a whole. Tapa enjoys a world of emotions, sentiments, hopes, ambitions, dreams and inspiration. There will hardly be a Pashtun who does not remember one or two Tappa. -

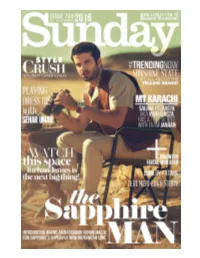

ISSUE-754.Pdf

ISSUE 754 | SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 EYE SPY Your favourite celebs and socialites hit the towns glossiest events 8 THE WEEK THAT WAS Our round-up of the hottest outfits this week 40 FASHION SHOOT: THE SAPPHIRE MAN 54 Introducing the super fly Adnan Malik as brand ambassador for Sapphire's incredible new menswear line #TRENDINGNOW Hello, yellow! 66 STYLE CRUSH: KHUBAN OMER KHAN 72 This talented and gorgeous lady is a total class act PLAYING DRESS UP WITH SEHAR UMAR 78 Now that's what we call ab fab! MY KARACHI Salima Feerasta AKA Karachista has a tête- à-tête with Team Janaan 84 RISING STAR Watch this space: Turhan James is the next big thing! 88 EDITOR’S PICKS Everything you need to know about what's hot in your metropolis this week 92 WEEKLY HOROSCOPES What do the stars have in store for you this week? 94 40 18 - 24 September 2016 www.sunday.com.pk www.sunday.com.pk 18 - 24 September 2016 41 66 18 - 24 September 2016 www.sunday.com.pk www.sunday.com.pk 18 - 24 September 2016 67 72 18 - 24 September 2016 www.sunday.com.pk www.sunday.com.pk 18 - 24 September 2016 73 WHAT SEPARATES SAPPHIRE MENSWEAR FROM THE REST OF THE MARKET? WAS IT A CHALLENGE TO TRANSLATE YOUR SIGNATURE AESTHETIC TO THIS LINE? KHADIJAH: Sapphire, as with it’s womenswear range, will specialise in fashionable affordable and functional quality clothing for men. I believe there is no one brand Sapphire Man, I didn't really know that they did menswear in Pakistan that embodies all that. -

Annual Impact Report January to December 2017

british pakistan foundation Engage. Unite. Empower Annual Impact Report January to December 2017 Message from the Chair of the Board I envisage that the British Pakistani community have their own platform and support system to take advantage of the country they are born in and contribute back to society within every sector of the UK community. We have started on the journey but there is a lot more that needs to be done. We undertook a strategic review in May 2016 when our new CEO Zahra Shah joined us to focus on professional development and supporting entrepreneurship through our key 3 programmes: Business and Professionals Programme, Women’s Programme and Young Professionals Programme, in order to empower the British Pakistani community in the UK. We need to make serious efforts to increase our membership over the coming years if we are to make a positive difference to the British Pakistani community in the UK. The future looks bright as we focus on empowering the Youth, Women, Professionals and Entrepreneurs in our community. I look forward to expanding our programmes nationwide in the coming years to enable this platform to benefit the British Pakistani community across the UK, particularly those members of the community who are most vulnerable. I invite you to join us in this movement. Asif Rangoonwala Message from the CEO I took over the role of the CEO in May 2016 and undertook a strategic review that resulted in a modified strategic direction enabling us to focus on empowering the British Pakistani community in the UK through professional development and supporting entrepreneurship. -

Cinema in Pakistan: Economics, Institutions and Way Forward

CINEMA Cinema in Pakistan: Economics, Institutions and Way Forward No. 2020:28 PIDE Working Papers Zulfiqar Ali Fahd Zulfiqar PIDE Working Papers No. 2020:28 Cinema in Pakistan: Economics, Institutions and Way Forward Zulfiqar Ali Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad. and Fahd Zulfiqar Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad. Acknowledgment: Our thanks to Dr. Nadeem Ul Haque for suggesting this valuable and unexplored topic and pointing out that film industry is an avenue of economic activity creating employment and value. PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS ISLAMABAD 2020 Editorial Committee Lubna Hasan Saima Bashir Junaid Ahmed Disclaimer: Copyrights to this PIDE Working Paper remain with the author(s). The author(s) may publish the paper, in part or whole, in any journal of their choice. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Islamabad, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pide.org.pk Fax: +92-51-9248065 Designed, composed, and finished at the Publications Division, PIDE. CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Lollywood: Emergence, Existence and Endurance 3 3. Institutions of Cinema in Pakistan 7 3.1. Film Trade Associations 7 3.2. Motion Picture Ordinance 9 3.3. National Film Development Corporation 9 3.4. Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC) 9 4. Economics of ‘New Cinema’ in Pakistan 10 4.1. Use of Modern Technology and ‘New Cinema’ 10 4.2. Commercial Success of ‘New Cinema’ 11 4.3. Multiplex Cinemas 12 4.4. Entertainment Duty 13 4.5. COVID-19 14 5. Existing Policy Debates 15 6. Policy Recommendations 16 References 17 List of Tables Table 1.