Excavations at Auchategan, Glendaruel, Argyll D N Marshall*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decision with Statement of Reasons of the First-Tier Tribunal for Scotland

Decision with Statement of Reasons of the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) under Regulation 10 of the Tenancy Deposit Schemes (Scotland) Regulations 2011 Chamber Ref: FTS/HPC/PR/20/0861 Re: Property at The Workshop Cottage, Clachan of Glendaruel, Argyll and Bute, PA22 3AA (“the Property”) Parties: Mr Robert Hayes, 20 Kilmun Court, Kilmun, Argyll and Bute, PA23 8SF (“the Applicant”) Paul Morley & Son Joinery & Building Contractor, Mrs Dawn Morley, The Old Steading, Clachan of Glendaruel, Argyll and Bute, PA22 3AA (“the Respondent”) Tribunal Members: Fiona Watson (Legal Member) and Ann Moore (Ordinary Member) Decision The First-tier Tribunal for Scotland (Housing and Property Chamber) (“the Tribunal”) determined that an order is granted against the Respondent(s) for payment of the undernoted sum to the Applicant(s): Sum of FOUR HUNDRED AND FIFTY POUNDS (£450) STERLING Background 1. An application was submitted to the Tribunal under Rule 103 of the First-tier Tribunal for Scotland Housing and Property Chamber (Procedure) Regulations 2017. Said application sought an order be made against the Respondent on the basis that the Respondent had failed to comply with his duties to lodge a deposit in a tenancy deposit scheme in terms of Regulation 3 of the Tenancy Deposit Schemes (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (“the 2011 Regulations”). The Case Management Discussion 2. A Case Management Discussion (“CMD”) took place on 17 August 2020 by way of tele-conference. Both parties were personally present. The Applicant submitted that he had entered into a tenancy agreement with the Respondents which commenced 1 July 2009. He had paid a deposit of £300 to the Respondent at the commencement of the tenancy. -

Kilmodan Sculptured Stones Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC086 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90318) Taken into State care: 1978 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KILMODAN SCULPTURED STONES We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KILMODAN SCULPTURED STONES BRIEF DESCRIPTION This small but significant collection of sculptured stones lies within an 18th century burial aisle in the south-east corner of Kilmodan parish churchyard. -

Delegated Decisions Report

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING DELEGATED DECISIONS MADE IN THE LAST MONTH Delegated Decisions Report Application Types: ADV - Application for Advertisement Consent AMSC - Approval of Matters in Conditions CAAD - Certificate Appropriate Aleternative Dev CLAWU - App. for Cert. of Law Use/Dev (Existing) CLWP - App. for Cert. of Law Use/Dev (Proposed) CONAC - App. for Conservation Area Consent CPD - Council Permitted Dev Consultation FDP - Forest Design Plan Consultation FELLIC - Felling Licence Consultation FGS - Forest Grant Scheme HH - High Hedges HSZCON - App. for Hazardous Substances Consent HYDRO - Hydro Board Consultation LIB - Application for Listed Building Consent MFF - Marine Fish Farm Application MIN - Application for Mineral Consent MPLAN - Masterplan NMA - App. for Non Material Amendment (sec 64) PACSCR - PAC Screening PAN - Proposal of Application Notice PNAGRI - Prior Notification Agriculture PNDEM - Prior Notification Demolition PNELEC - Prior Notification Electricity PNFOR - Prior Notification Forestry PNMFF - Prior Notification Marine Fish Farm PNMRE - Prior Notification Micro Renewable Energy PNRAIL - Railway Works Notification PNTEL - Prior Notification Telecommunications PP - Planning Permission PPP - Planning Permission in Principle PREAPP - Preliminary Enquiry RDCRP - Rural Development Contract S36 - Consultation Electricity Works S37 - Consultation Overhead Line SCOPE - Scoping Opinion SCREEN - Screening Opinion SCRSCO - Screening and Scoping Opinion TELNOT - Telecommunications Notification TPO - Tree Preservation Order -

Glenan Wood Feasibility Study and Business Plan

Glenan Wood Feasibility Study and Business Plan Bioblitz at Glenan June 2018 Final Version October 2018 Glenan Wood – Feasibility Study and Business Plan Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Study purpose 3 Background to Glenan Wood 4 Options for developing Glenan and recommendations as to preferred uses 5 Risks associated with community ownership and management of Glenan and recommended mitigation 6 Delivery process and funding strategy 7 Business plan - income and expenditure 8 Connecting with local and national priorities and outcomes 9 Conclusions Appendix 1 Socio economic profile Appendix 2 FOGW Trustees biographies Appendix 3 FOGW Signed Constitution Appendix 4 Expressions of support Appendix 5 Job Description Appendix 6 Ideas for Improvement and Facilities/Activities for Community Benefit Appendix 7 Maps Appendix 8 Projected income and expenditure Appendix 9 Project profiles Appendix 10 PAWS Report The report authors, acknowledge and thank FOGW Trustees, their supporters and FES officers for their help in preparing this report. Bryden Associates with Graeme Scott & Co., Chartered Accountants Executive Summary Friends of Glenan (FOGW) is a Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organisation SCIO No: SC047803. Established 06 October 2017 to pursue ownership of the 146 ha Glenan Wood. Glenan Wood has been identified for disposal by the current owners, Forest Enterprise Scotland (FES). Community consultations provided a mandate for FOGW Trustees to enter the FES Community Asset Transfer Scheme (CATS) and seek community ownership. For FES to approve a CAT, FOGW must demonstrate, through a feasibility study and business plan, that they understand the commitment involved in taking ownership, that they have the support of the local community and that they can present a viable management proposition with actions that maintain and enhance the public interest. -

04/11/20 Page 1 Location :THE ME

Printed at 11:01 on 29/05/20 Appeals to be Heard by the Local Valuation Panel Date of Hearing : 04/11/20 Page 1 Location :THE MEETING ROOM, THE LOCH FYNE HOTEL, NEWTOWN, INVERARAY, ARGYLL Description / Appellant / Appeal Appealed Valuer dealing with appeal Property Reference Situation Agent Flag Value _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 01/97/A97101/0051 SHOOTING RIGHTS T L NELSON CP1A 4,350 Fiona Gillies ACHNACLOICH & AUCHENLOCHAN THE ESTATES OFFICE 01586 555307 ARDCHATTAN & MUCKAIRN GIBRALTAR STREET [email protected] ARGYLL & BUTE OBAN PA34 4AY ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 01/97/A97101/0056 SHOOTING RIGHTS FERGUS FLEMING CP1A 6,300 Fiona Gillies ARDMADDY SAVILLS 01586 555307 ARDCHATTAN & MUCKAIRN EARN HOUSE [email protected] ARGYLL & BUTE BROXDEN BUSINESS PARK LAMBERKINE DRIVE PERTH PH1 1RA ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 01/97/A97101/0059 SHOOTING RIGHTS SARAH TROUGHTON CP1A 8,100 Fiona Gillies ARDACHY JULIAN CLARKE 01586 555307 ARDCHATTAN & MUCKAIRN ATHOLL ESTATES [email protected] ARGYLL & BUTE BLAIR ATHOLL -

COWAL Sustainable, Unsustainable and Historic Walks and Cycling in Cowal

SEDA Presents PENINSULA EXPEDITION: COWAL Sustainable, Unsustainable and Historic walks and cycling in Cowal S S R Road to Inverarary and Achadunan F * * Q G D Kayak through the * Crinnan Canal E P N B K A C Kayak to Helensburgh O * * * Z L Dunoon T Map J Train to Glasgow Central U X I H V M W Y To Clonaig / Lochranza Ferry sponsored by the Glasgow Institute Argyll Sea Kayak Trail of Architects 3 ferries cycle challenge Cycle routes around Dunoon 5 ferries cycle challenge Cycle routes NW Cowal Cowal Churches Together Energy Project and Faith in Cowal Many roads are steep and/or single * tracked, the most difcult are highlighted thus however others Argyll and Bute Forrest exist and care is required. SEDA Presents PENINSULA EXPEDITION: COWAL Sustainable, Unsustainable and Historic walks and cycling in Cowal Argyll Mausoleum - When Sir Duncan Campbell died the tradition of burying Campbell Clan chiefs and the Dukes of Argyll at Kilmun commenced, there are now a total of twenty Locations generations buried over a period of 500 years. The current mausoleum was originally built North Dunoon Cycle Northern Loop in the 1790s with its slate roof replaced with a large cast iron dome at a later date. The A - Benmore Botanic Gardens N - Glendaruel (Kilmodan) mausoleum was completely refur-bished in the late 1890s by the Marquis of Lorne or John B - Puck’s Glen O - Kilfinan Church George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll. Recently the C - Kilmun Mausoleum, Chapel, P - Otter Ferry mausoleum has again been refurbished incorporating a visitors centre where the general Arboreum and Sustainable Housing Q - Inver Cottage public can discover more about the mausoleums fascinating history. -

Patsy Dyer the Viking Invasion of Otter Ferry Transcript

Forest Heritage Scotland Discover your roots in Scotland’s forests www.forestheritagescotland.com The Viking Invasion of Otter Ferry by Patsy Dyer Long, long ago at the time when the Vikings were invading Scotland, there was a king in Argyll called Constantine and he was a very wiley, strong warrior. He had set, all along the coast, spies to watch out for an attack coming from Ireland or the Isle of Man where Vikings had their strongholds. One day, he was informed that a spy had seen hundreds of ships in a fleet coming over from Ireland. Quickly Constantine rallied his army and he marched north to where he was certain the Vikings would choose to land. This is a site on Loch Fyne called Otter Ferry. The name otter not meaning the soft, silky creature that lives between the water and the shore, but otter in Gaelic, translated, means a promontary of land, jutting out in to the sea, and there at Otter there is a long sandbank that goes out for mile into Loch Fyne and at low tide it is a sandbank as wide as a small country lane. When Constantine and his army arrived at Glendaruel, above Otter, they hid amongst the trees, waiting. Constantine thought what a very clever place it was to land. Such an excellent breakwater where the Vikings could moor all of their ships on the leeside, where they could disembark and be ready for battle. As he stood watching the boats coming up Loch Fyne, he realised by looking at the signs painted on the sails, that it was King Ragnald that was in charge of this onslaught and that his brother Godfrey was in charge of the vanguard. -

View Preliminary Assessment Report Appendix D Assessment Summary

Access to Argyll & Bute (A83) Strategic Environmental Assessment & Preliminary Engineering Services Route Corridor Preliminary Assessment Route Corridor 8a – North Ayrshire – Cairndow via Colintraive Route Corridor Details Route Corridor Option Route Corridor 8a – North Ayrshire – Cairndow via Colintraive Route Corridor Description This route corridor is a combination of new offline carriageway and online upgrading works which generally follows the existing road network, with new fixed link crossings to the Isle of Bute and Cowal. The route corridor includes a connection from the A78 Trunk Road in North Ayrshire to Cowal via a 3.0km and 2.53km fixed link crossing between the mainland (within the vicinity of Portencross) and the Isle of Bute via Little Cumbrae Island and a 0.7km fixed link crossing between the Isle of Bute and Cowal (within the vicinity of the Colintraive to Rhubodach ferry crossing). From east to west, a new section of carriageway will be required between the A78 Trunk Road and the fixed link crossing to the Isle of Bute. Once on the Isle of Bute, the route corridor then generally follows the existing B881, A844 and A886. Once on Cowal the route corridor generally follows the A886 again and thereafter the A815 to tie back into the A83 Trunk Road at Cairndow. The approximate length of the route corridor where no road currently exists is approximately 6.7km with the full route corridor approximately 90km in length. The fixed link crossings to the Isle of Bute will provide significant technical challenges. This area is used by large marine vessels as well as Ministry of Defence (MOD) submarines which are based at Faslane and Coulport. -

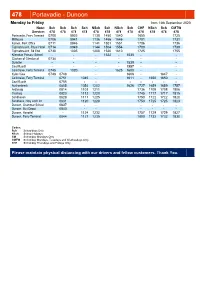

478 Portavadie - Dunoon

478 Portavadie - Dunoon Monday to Friday from 14th September 2020 Note: Sch Sch Sch Sch NSch Sch NSch Sch CHF NSch Sch CMTW Service: 478 478 478 478 478 478 478 478 478 478 478 478 Portavadie, Ferry Terminal 0700 0935 1130 1450 1540 1655 1725 Millhouse 0706 0941 1136 1456 1546 1701 1731 Kames, Post Office 0711 0946 1141 1501 1551 1706 1736 Tighnabruaich, Royal Hotel 0714 0949 1144 1504 1554 1709 1739 Tighnabruaich, Rd End 0730 1005 1200 1520 1610 1725 1755 Kilmodan Primary School - - - 1522 - 1535 - - Clachan of Glendaruel 0734 - - - - - - Duiletter - - - - 1539 - - Coal Ruadh - - - - 1557 - - Colintraive, Ferry Terminal 0745 1020 - 1625 1600 - - Kyles View 0748 0748 - 1606 - 1647 - Colintraive, Ferry Terminal 0751 1045 - 1611 - 1650 1650 - Coal Ruadh 0755 - - - - - - - Auchenbreck 0805 1054 1202 1626 1727 1659 1659 1757 Ardtaraig 0814 1103 1211 1736 1708 1708 1806 Clachaig 0823 1112 1220 1745 1717 1717 1815 Sandhaven 0828 1117 1225 1750 1722 1722 1820 Sandbank, Holy Loch Inn 0831 1120 1228 1753 1725 1725 1823 Dunoon, Grammar School 0837 - - - - - - Dunoon, Bus Depot 0840 - - - - - - Dunoon, Hospital - 1124 1232 1757 1729 1729 1827 Dunoon, Ferry Terminal 0844 1127 1235 1800 1732 1732 1830 Codes: Sch Schooldays Only NSch School Holidays CM Schoolday Mondays Only CMTW Schoolday Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays Only CHF Schoolday Thursdays and Fridays Only Please maintain physical distancing with our drivers and fellow customers. Thank You. 478 Dunoon - Portavadie Monday to Friday from 14th September 2020 Note: Sch Sch Sch NSch NSch Sch NSch -

Dunoon Charrette Report

ThinkDunoon Charrette Charrette Report Scottish Regeneration Forum & Argyll & Bute Council 21.07.2017 Contents Introduction 6 Appendices 124 A: Physical Project Sheets 126 Charrette Process 12 B: Community Engagement 176 Charrette Engagement & Events 12 C: Socio-Economic Analysis 192 Digital Media/Media 14 D: Transport Analysis 200 Think Ideas 16 E: Property Analysis 206 F: Charrette Comments 209 Analysis 22 G: Pecha Kucha 231 Wider Context 22 H: Briefing Notes 232 Landscape Setting 24 I: Art Strategy 245 Town Centre 26 Historical Context 30 Socio-Economic Context 32 Assets 34 Achievements 36 Challenges & Opportunities 38 Vision & Objectives 42 Vision 42 Objectives 42 Projects 44 Project Theme 1: Think Community 46 > Strengths, Challenges & Aims 46 > Project Action Plan 48 Project Theme 2: Think Local Economy 62 > Strengths, Challenges & Aims 62 > Project Action Plan 64 Project Theme 3: Think Tourism 70 > Strengths, Challenges & Aims 70 > Project Action Plan 72 Project Theme 4: Think Place 78 > Strengths, Challenges & Aims 78 > Dunoon 2027 Masterplan 80 > Project Action Plan 84 Next Steps 108 Austin-Smith:Lord LLP Project Priority 110 Glasgow Funding Opportunities 116 Bristol Delivery Plan 119 Cardiff Alliance for Action & The Town Team 120 Liverpool Conclusion 122 London 296 St Vincent Street, Glasgow, G2 5RU +44 (0)141 223 8500 [email protected] www.austinsmithlord.com Introduction Introduction ThinkDunoon Charrette Context ThinkDunoon Charrette Objectives ‘Alliance for Action’ potential ThinkDunoon Consultants Supported by -

A Charming Scottish Farmhouse with Tearoom and Gift Shop

A CHARMING SCOTTISH FARMHOUSE WITH TEAROOM AND GIFT SHOP millcroft millhouse, tighnabruaich, argyll, pa21 2bw The Farmhouse A CHARMING SCOTTISH FARMHOUSE WITh TEAROOM AND GIFTSHOP millcroft, millhouse, tighnabruaich, argyll, pa21 2bw Porch w reception hallway w sitting room w drawing room w kitchen w laundry room w shower room w 4 bedrooms w family bathroom w The Barn tearoom and gift shop Dunoon: 26 miles Glasgow: 88 miles Glasgow Airport: 78 miles Directions From Glasgow, head north, and follow the A82 up Loch Lomond. At Tarbet, turn left onto the A83. At the junction with the A815 turn left again, and follow this road to Strachur, then take the A886 signposted Tighnabruaich and Colintraive. After passing through Glendaruel (15 miles) bear right on the A8003, signposted Tighnabruaich. Alternatively, take the M8 and A8 west and take the ferry from Gourock to Dunoon. From Dunoon, take the A815 north, signposted Glasgow. Approximately four miles north of Dunoon, turn left onto the B836 signposted Colintraive and Bute Ferry. At the T-junction with the A886, turn right towards Glendaruel and then left onto the A8003, signposted Tighnabruaich. On entering Tighnabruaich turn left down the winding road which descends towards the waterfront. At the shore turn right, pass An Lochan (former Royal Hotel) on the right, then pass the shinty pitch on the left and at the village shop in Kames turn right signed for Portavaddie. Continue on the B8000 to the village of Millhouse and turn left signed for Millcroft – The Barn. The property will then be seen on the right hand side. -

Loch Lomond & Cowal

Loch Lomond & Cowal Way app and guide book How to get to the Loch Lomond & Cowal Way LOCH LOMOND Though the Loch Lomond & Cowal Way is fully waymarked, users may By road there are two main routes to the path. From Glasgow/ wish to download the free app, or purchase the guide book, to add central belt of Scotland take the M8 towards Greenock and & COWAL WAY value to your adventure. The mobile app is free to download. Check continue to drive to Gourock. There is a car ferry called Western Scotland in 57 miles www.lochlomondandcowalway.org for details. The app will show your Ferries (distinctive red ferries) and this regular 20 minute sea position on the path, using a map-based system with GPS. Additional journey will take you to Dunoon. From Dunoon drive to Portavadie information includes an overview of the path in manageable sections, which is approximately 40 minutes by car. Alternatively, if you some key attractions and images supported with text and audio, want to start the walk at Inveruglas, drive along Loch Lomond on and much more. Our detailed guide book, available to purchase from the A82, Inveruglas is less than one hour from Glasgow. Rucksack Readers at www.rucsacs.com/book/loch-lomond-cowal- If you wish to travel by public transport, there is a Citylink bus way, provides readers with a wealth of information, including detailed from Glasgow Buchanan Street Bus Station (Fort William/Skye analysis of the path, easy-to-use maps, local heritage and wildlife, service) to Sloy next to Inveruglas, which takes approximately transport links, and much, much more.