Cu.1.O FOCUS: Monet's Lmpression, Sunrise, Monet's Gare St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degas: Agency in Images of Women

Degas: Agency in Images of Women BY EMMA WOLIN Edgar Degas devoted much of his life’s work to the depiction of women. Among his most famous works are his ballet dancers, bathers and milliners; more than three- quarters of Degas’ total works featured images of women.1 Recently, the work of Degas has provoked feminist readings of the artist’s treatment of his subject matter. Degas began by sketching female relatives and eventually moved on to sketch live nude models; he was said to have been relentless in his pursuit of the female image. Some scholars have read this tendency as obsessive or pathological, while others trace Degas’ fixation to his own familial relationships; Degas’ own mother died when he was a teenager.2 Degas painted women in more diverse roles than most of his contemporaries. But was Degas a full-fledged misogynist? That may depend on one’s interpretation of his oeuvre. Why did he paint so many women? In any case, whatever the motivation and intent behind Degas’ images, there is much to be said for his portrayal of women. This paper will attempt to investigate Degas’ treatment of women through criticism, critical analysis, visual evidence and the author’s unique insight. Although the work of Degas is frequently cited as being misogynistic, some of his work gives women more freedom than they would have otherwise enjoyed, while other paintings, namely his nude sketches, placed women under the direct scrutiny of the male gaze. Despite the ubiquity 1 Richard Kendall, Degas, Images of Women, (London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1989), 11. -

Edgar Degas: a Strange New Beauty, Cited on P

Degas A Strange New Beauty Jodi Hauptman With essays by Carol Armstrong, Jonas Beyer, Kathryn Brown, Karl Buchberg and Laura Neufeld, Hollis Clayson, Jill DeVonyar, Samantha Friedman, Richard Kendall, Stephanie O’Rourke, Raisa Rexer, and Kimberly Schenck The Museum of Modern Art, New York Contents Published in conjunction with the exhibition Copyright credits for certain illustrations are 6 Foreword Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty, cited on p. 239. All rights reserved at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 7 Acknowledgments March 26–July 24, 2016, Library of Congress Control Number: organized by Jodi Hauptman, Senior Curator, 2015960601 Department of Drawings and Prints, with ISBN: 978-1-63345-005-9 12 Introduction Richard Kendall Jodi Hauptman Published by The Museum of Modern Art Lead sponsor of the exhibition is 11 West 53 Street 20 An Anarchist in Art: Degas and the Monotype The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation. New York, New York 10019 www.moma.org Richard Kendall Major support is provided by the Robert Lehman Foundation and by Distributed in the United States and Canada 36 Degas in the Dark Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III. by ARTBOOK | D.A.P., New York 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd floor, New York, NY Carol Armstrong Generous funding is provided by 10013 Dian Woodner. www.artbook.com 46 Indelible Ink: Degas’s Methods and Materials This exhibition is supported by an indemnity Distributed outside the United States and Karl Buchberg and Laura Neufeld from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Canada by Thames & Hudson ltd Humanities. 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX 54 Plates www.thamesandhudson.com Additional support is provided by the MoMA Annual Exhibition Fund. -

Bathing in Modernity: Undressing the Influences Behind Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt's Baigneuses Maiji Castro Department Of

Bathing in Modernity: Undressing the Influences Behind Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt’s Baigneuses Maiji Castro Department of Art History University of Colorado - Boulder Defended October 28, 2016 Thesis Advisor Marilyn Brown | Department of Art History Defense Committee Robert Nauman | Department of Art History | Honors Chair Priscilla Craven | Department of Italian Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………...………………………………………...3 Introduction………………………..…………...………………………………………...4 1 Visions of the Female Nude……..…….…………………………………………..….6 Testing the Waters Evolution In Another Tub 2 The Bourgeois Bather……………...………………………………………………….23 An Education A Beneficial Partnership A New Perspective 3 Bathing in Modernity…………………………………………………….………..…...41 Building the Bridge Similar Circumstances Cleanliness and Propriety 4 Epilogue.................................................................................................................54 Full Circle The Future Conclusion Illustrations............................................................................................................64 Bibliography………...…………………………………………………………………..74 2 Abstract This thesis examines how the motifs used in bathing genre paintings from Greek and Roman myths to eighteenth-century eroticism are evident in the bathing series of Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt. The close professional relationship of Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt is evident in the shared themes and techniques in their work and in personal accounts from letters by each other and their contemporaries. Both -

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM: Online Links: Edgar Degas – Wikipedia Degas' Bellelli Family - The Independent Degas's Bellelli Family - Smarthistory Video Mary Cassatt - Wikipedia Mary Cassatt's Coiffure – Smarthistory Cassatt's Coiffure - National Gallery in Washington, DC Caillebotte's Man at his Bath - Smarthistory video Edgar Degas (1834-1917) was born into a rich aristocratic family and, until he was in his 40s, was not obliged to sell his work in order to live. He entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1855 and spent time in Italy making copies of the works of the great Renaissance masters, acquiring a technical skill that was equal to theirs. Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas In this early, life-size group portrait, Degas displays his lifelong fascination with human relationships and his profound sense of human character. In this case, it is the tense domestic situation of his Aunt Laure’s family that serves as his subject. Apart from the aunt’s hand, which is placed limply on her daughter’s shoulder, Degas shows no physical contact between members of the family. The atmosphere is cold and austere. Gennaro, Baron Bellelli, is shown turned toward his family, but he is seated in a corner with his back to the viewer and seems isolated from the other family members. He had been exiled from Naples because of his political activities. Laure Bellelli stares off into the middle distance, significantly refusing to meet the glance of her husband, who is positioned on the opposite side of the painting. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As a Partial Fulfillment Of

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copy of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all of part of this thesis. Signature: Randi L. Fishman April 5, 2010 Date “A Careful Cruelty, A Patient Hate”: Degas’ Bathers in Pastel and Sculpture by Randi L. Fishman Dr. Linda Merrill Department of Art History Dr. Linda Merrill Adviser Dr. Sidney Kasfir Committee Member Dr. Brett Gadsden Committee Member April 5, 2010 Date “A Careful Cruelty, A Patient Hate”: Degas’ Bathers by Randi L. Fishman Adviser: Dr. Linda Merrill An abstract of a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Department of Art History 2010 Abstract “A Careful Cruelty, A Patient Hate”: Degas’ Bathers in Pastel and Sculpture By Randi L. Fishman This paper analyzes the themes of misogyny, twisted sexual fantasy, and grotesque eroticism in Degas’ Bathers sculptures and pastels. Degas’ Bathers series is a contemporary and cultural deconstruction of the nude as the ideal of feminine beauty, where the artist produces a twisted erotic fantasy, informed by his own misogyny and contemporary values and practices regarding sexuality, prostitution, and bathing. -

Japanese Influence on Western Impressionists: the Reciprocal Exchange of Artiistic Techniques Emma Wise Parkland College

Parkland College A with Honors Projects Honors Program 2019 Japanese Influence on Western Impressionists: The Reciprocal Exchange of Artiistic Techniques Emma Wise Parkland College Recommended Citation Wise, Emma, "Japanese Influence on Western Impressionists: The Reciprocal Exchange of Artiistic Techniques" (2019). A with Honors Projects. 262. https://spark.parkland.edu/ah/262 Open access to this Essay is brought to you by Parkland College's institutional repository, SPARK: Scholarship at Parkland. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emma Wise ART 162 – A with Honors Japanese Influence on Western Impressionists: The reciprocal exchange of artistic techniques During the nineteenth century, Paris was at the heart of modern art movements. It was during this time the Impressionist painters began to display their work in salons. Occurring at the same time was the influx of Japanese goods into Europe, including the artistic products. In Paris there was a large exhibition of Japanese ukiyo-e prints at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts during the spring of 1890 (Ives). The Japanese woodblock prints had an impact on western art and is visible in the work of the Impressionists. This can be seen through the painting and printmaking produced during the nineteenth century. The Impressionist movement paralleled Japan during the Edo period. During the two time periods, there was an increase of leisure time which led to the creation of art. In Japan, the creation of this art created a growing industry of accessible art. The increased leisure time in Paris fueled the art community. During the Edo period in Japan, there was an increase in economic growth that strengthened the middle class. -

Parsing Edgar Degas's Le Pédicure

Marni Reva Kessler Parsing Edgar Degas’s Le Pédicure Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 13, no. 2 (Autumn 2014) Citation: Marni Reva Kessler, “Parsing Edgar Degas’s Le Pédicure,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 13, no. 2 (Autumn 2014), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn14/kessler- on-parsing-edgar-degas-le-pedicure. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Kessler: Parsing Edgar Degas’s Le Pédicure Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 13, no. 2 (Autumn 2014) Parsing Edgar Degas’s Le Pédicure by Marni Reva Kessler The silvery wink of the instrument wielded by the male figure in Edgar Degas’s Le Pédicure of 1873 (fig. 1) draws our eye to the focus of the painting, to the place where this middle-aged man works on the toe of a drowsy young girl who is slumped on a chintz banquette. Representing the artist’s ten-year-old American niece Joe Balfour,[1] Le Pédicure surprises in both its subject matter and Degas’s handling of it. Looking at the spot where the sharp tool meets Joe’s youthful flesh, we might wonder why Degas wanted to represent something so unpleasant. We may even experience a quick shiver of disgust as we take in what appears to be happening in the image: the man is in the process of lifting the edge of Joe’s toenail from her skin by passing the steely instrument between the two. Despite its subject matter, the painting still draws us in with its comfortable domestic setting, its plush banquette, marble- topped bureau, gilt-framed mirror, pitcher, and thick-lipped blue and white washbowl. -

Public Exhibitions of Drawing in Paris, France (1860-1890)

PUBLIC EXHIBITIONS OF DRAWING IN PARIS, FRANCE (1860-1890): A STUDY IN DATA-DRIVEN ART HISTORY by Debra J. DeWitte APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: _______________________________________________ Dr. Richard Brettell, Chair _______________________________________________ Dr. Maximilian Schich _______________________________________________ Dr. Mark Rosen _______________________________________________ Dr. Michael L. Wilson Copyright 2017 Debra J. DeWitte All Rights Reserved Jaclyn Jean Gibney, May you work hard and dream big. PUBLIC EXHIBITIONS OF DRAWING IN PARIS, FRANCE (1860-1890): A STUDY IN DATA-DRIVEN ART HISTORY by DEBRA J. DEWITTE, BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES - AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish first and foremost to thank my advisor Dr. Richard Brettell for his incredible support and generosity during this journey. I was also fortunate to have the ideal group of scholars on my committee. Dr. Maximilian Schich introduced me to the world of data with enthusiasm and genius. Dr. Mark Rosen has the gift of giving both scholarly and practical advice. Dr. Michael Wilson has been a wise guide throughout my graduate career, and fuels a desire to improve and excel. I would also like to thank the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History for creating an envirnonment for intellectual exchange, from which I have benefited greatly. The Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History also funded travel to study sources critical for my topic. Numerous scholars, librarians and archivists were invaluable, but I would especially like to thank Laure Jacquin de Margerie, Isabelle Gaëtan, Marie Leimbacher, Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Axelle Huet, and Jon Whiteley. -

Reading the Animal in Degas's Young Spartans

Martha Lucy Reading the Animal in Degas's Young Spartans Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 2 (Spring 2003) Citation: Martha Lucy, “Reading the Animal in Degas's Young Spartans,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 2 (Spring 2003), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring03/222- reading-the-animal-in-degass-young-spartans. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2003 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Lucy: Reading the Animal in Degas‘s Young Spartans Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2, no. 2 (Spring 2003) Reading the Animal in Degas's Young Spartans by Martha Lucy In Edgar Degas's studio a work begun in 1860 sat dormant, unfinished, for almost 20 years. It was a large-scale history painting—one of the few Degas would produce—and it pictured classical figures, linear and abstracted, locked in frieze-like arrangement on either side of a silent space. After seeing the abandoned canvas in the artist's studio in 1879, the Italian art critic Diego Martelli described it as "one of the most classicizing paintings imaginable" and suspected that it remained unfinished precisely for that reason: "Degas could not fossilize himself in a composite past," he explained in a lecture later that year.[1] Soon after Martelli's remarks, Degas returned to the painting, removing the classicizing architecture and making several compositional changes. And in one of the most unusual revisions of his career, he painted over the classical profiles, replacing them with distinctly unidealized heads.[2] The result was his Young Spartans, now at the National Gallery, London; the painting's original appearance is best approximated by the classicizing grisailles in the Art Institute of Chicago. -

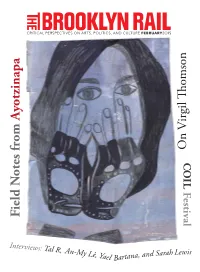

Field N Otes from Ayotzinapa

omson T Ayotzinapa On Virgil Virgil On C O IL Festival Field Notes from Notes Field arah Lewis a, and S Interviews: Tal R, An-My Lê, Yael Bartan Brett Bigbee TWO PAINTINGS Opening Thursday, February 27th at 5:30 pm ALSO ON VIEW Lois Dodd: Recent Panel Paintings Alexandre Gallery Fuller Building 41 East 57th Street New York 212.755.2828 www.alexandregallery.com Josie Over Time, 2011–15, oil on linen, 13 3/8 x 12 1/8 inches Dear Friends and Readers, Tied to a tree together one barking Te other has a bad ear Squeals at him —Aram Saroyan aving kept up with the insightful articles that appeared in omson our Field Notes section, as well as those in the NY Times, the T Nation, and other news sources that cover social and political Ayotzinapa H afairs around the world, I was deeply saddened, like most of us, by the Charlie Hebdo shooting on January 7, which quickly became the top news story, overshadowing the endless bombings in Baghdad; Virgil On the Ebola crisis in West Africa; the missing AirAsia fight 8501; the CO ISIS hostage situation; and Winter Storm Frona that took 16 lives in IL the Midwest, the Great Lakes, and the Northeast, among many other Festival natural and human disasters. How is it that we can be subjected to steady and simultaneous streams of bad news and consumerist distraction? from Notes Field How can we still aspire to notions of freedom and justice while we are Tal R haunted by religious wars, ideological genocides, and other masochistic Inte “m” 2014. -

Edgar Degas: Intimität Und Pose

Philippa Kaina exhibition review of Edgar Degas: Intimität und Pose Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Citation: Philippa Kaina, exhibition review of “Edgar Degas: Intimität und Pose,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/ autumn09/edgar-degas-intimitaet-und-pose. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Kaina: Edgar Degas: Intimität und Pose Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Edgar Degas: Intimität und Pose Introduction by Hubertus Gassner, with essays by Werner Hofmann, Pablo Jiménez Burillo, Patrick Bade, Nadia Arroyo Rice, Richard Thomson, Philippe Saunier and William Tucker. München: Hirmer Verlag, 2009. 336 pp; 148 color plates; 50 b/w plates, 60 color ills; 28 b/w ills.; appendices; chronology; bibliography. €45 (clothbound) ISBN: 978-3-7774-9035-9 Intimität und Pose (Pose and Intimacy), an exhibition devoted to Edgar Degas' imagery of the female body at the Hamburg Kunsthalle is one of a series of recent shows on the artist. Following a related (differently themed and slightly smaller) exhibition Degas: El Proceso de la Creación (Degas: the Process of Creation) in Madrid at the Fundación MAPFRE it also coincided, entirely coincidentally, with the first major retrospective of the artist in the southern hemisphere: Degas: Master of French Art at the National Gallery of Art, Canberra. In the wake of the landmark 1988-89 Degas retrospective (Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) there have been numerous smaller-scale exhibitions of the artist's work relating to various aspects of his practice. -

Degas: Painting from Memory and Imagination

Degas: Painting from Memory and Imagination `At the moment, it is fashionable to paint pictures where you can see what time it is, like on a sundial, I don't like that at all. A painting requires a little mystery, some vagueness, some fantasy. When you always make your meaning perfectly plain you end up boring people. Even working from life, you most compose. Some people think it is forbidden!' ` On this subject, Monet told me: When Jongkind needed a house or a tree, he would turn round and take them from behind him.' ( Memories of Degas, Georges Jeanniot) Unlike the most of his contemporaries, Degas was an Impressionist who did not derive pleasure from painting at plein air where the painter is exposed to natural light. Instead, he always preferred to work in his studio, mainly from memory, with his desirable artificial type of light which was an indispensable factor of almost all of his paintings, the brown sauce as he called it. The question is why he had chosen that unique captivating style of painting from memory and how his imagination helped him to push back the boundaries of suffering and find his way to absolute freedom in the way of illustration. Ingres's Influence Degas's artistic life can be divided in three different eras [7]. The apprentice years (1850-1870), the Impressionists era (1870-1885) and the late maturity (1886-1912). During the apprentice years, he was influenced by both contemporary and old masters. Ingres for example, the French Neo-Classicist painter, played an important role as a mentor in shaping Degas's artistic character.