The End of Science?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

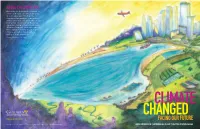

Facing Our Future

ABOUT THE COVER ART Get ready for the end of our world as we know it. How can we not despair at such a prospect? Roll up the sleeves on imagination, compassion, and science and let’s get ready for our new world. The poster for Gustavus Adolphus College’s Nobel Conference “Climate Changed” illustrates some of the solutions for living in a changed climate, as well as the attendant reality of mass migrations. Sharon Stevenson, Designer CLIMATE CHANGEDFACING OUR FUTURE 800 West College Avenue | Saint Peter, MN 56082 | gustavus.edu/nobelconference NOBEL CONFERENCE 55 | SEPTEMBER 24 & 25, 2019 | GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS COLLEGE NOBEL CONFERENCE 55 I love being in nature, whether it is time at our family cabin WELCOin northern Minnesota, a walk in the Linnaeus Arboretum at ME Gustavus, or the trip I took this summer with my husband to camp and hike in the western national parks. Like many people, I find nature to be a source of renewal, a connection to the Earth and the Divine, and a reminder of the interconnectedness of creation. Also, like many people, I am concerned about our world. As scientific evidence of human-caused climate change is mounting, members of the Gustavus community are working to understand this crisis and its local and Alfred Nobel had a vision of global effects. On campus, several groups are working on this great challenge a better world. He believed of our time. For example, the President’s Environmental Sustainability Council that people were capable of and the student-led Environmental Action Coalition are leading campus initiatives to reduce our helping to improve society campus energy use by 25 percent in the next five years and make improvements in recycling and through knowledge, science, and waste management with the goal of becoming a zero-waste campus, with 90 percent of solid waste humanism. -

Gustavus Quarterly

01 Fall 07 masters.2bak:Winter 03-04 MASTERS.1 8/8/07 11:11 AM Page 1 THE GustavusGustavus Adolphus College Fall 2007 QUARTERLY BigBig stinkstink onon campuscampus Plus I Three Views of Virginia I Stadiums Come and Go I Stringing Along with the Rydell Professor 01 Fall 07 masters.2bak:Winter 03-04 MASTERS.1 8/8/07 11:11 AM Page 2 G THE GUSTAVUS QUARTERLY Fall 2007 • Vol. LXIII, No. 4 Managing Editor Steven L. Waldhauser ’70 [email protected] Alumni Editors Randall M. Stuckey ’83 [email protected] Barbara Larson Taylor ’93 [email protected] Design Sharon Stevenson [email protected] Contributing Writers Laura Behling, Kathryn Christenson, Gwendolyn Freed, Teresa Harland ’94, Tim Kennedy ’82, Donald Myers ’83, Brian O’Brien, Paul Saulnier, Dana Setterholm ’07, Randall Stuckey ’83, Matt Thomas ’00, Thomas Young ’88 Contributing Photographers Anders Björling ’58, Ashley Henningsgaard ’07, Joel Jackson ’71, Joe Lencioni ’05, Tom Roster, Wayne Schmidt, Sharon Stevenson, Matt Thomas ’00, Stan Waldhauser ’71 Articles and opinions presented in this magazine do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors or official policies of the College or its board of trustees. The Gustavus Quarterly (USPS 227-580) is published four times annually, in February, May, August, and November, by Gustavus Adolphus College, St. Peter, Minn. Periodicals postage is paid at St. Peter, MN 56082, and additional mailing offices. It is mailed free of charge to alumni and friends of the College. Circulation is approximately 35,000. Postmaster: Send address changes to The Gustavus Quarterly, Office of Alumni Relations, Gustavus Adolphus College, 800 W. -

Institute for Empirical Research in Economics University of Zurich

Ernst Fehr INSTITUTE FOR EMPIRICAL RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF ZURICH Blümlisalpstr. 10 Tel. (41) (44) 634 37 09 CH-8006 Zürich Fax (41) (44) 634 49 07 Email: [email protected] Curriculum Vitae..............................................................................................................................2 Awards and Distinctions...................................................................................................................4 Editorial Commitments and Duties ............................................................................................6 Current Research Projects ...........................................................................................................7 Teaching Activities .........................................................................................................................8 Refereeing Activities for the following Journals..................................................................10 Book Reviews ..................................................................................................................................10 Presentations at International Conferences................................................................................11 Presentations in Research Seminars ......................................................................................14 Membership in Scientific Organizations.......................................................................................16 Research Grants............................................................................................................................17 -

Curriculum Vitae: Sylvester James Gates, Jr

Curriculum Vitae: Sylvester James Gates, Jr. Personal Information Date of Birth: December 15, 1950 Place of Birth: Tampa, FL, USA Departmental Address: Brown University Department of Physics Box 1843 Providence, RI 02912 USA Webpage: https://sites.brown.edu/sjgates/ Email Address: [email protected] Undergraduate Education: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1969-1973 B.Sc. in Mathematics, M.I.T., June 1, 1973 B.Sc. in Physics, M.I.T., September 12, 1973 Undergraduate Thesis: (Physics) “On the Feasibility of Generating Electricity with a Rijke Tube.” This thesis is an analysis of the acoustical, mechanical, and thermodynamical problems associated with using the Rijke phenomena to generate electricity. Thesis Advisor: Professor K. U. Ingard Graduate Education: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1973-1977, Ph.D. Physics, M.I.T., June 6, 1977. Graduate Thesis: “Symmetry Principles in Selected Problems of Field Theory” Doctoral thesis describes an investigation of the uses of symmetry principles in unified models of the Weak and Electromagnetic Interactions and in supersymmetric models. First Ph.D. thesis at MIT on the topic of supersymmetry. Thesis Advisor: Professor J. E. Young Postdoctoral Experience: Research Fellow, California Institute of Technology, 1980-1982, Junior Fellow. Harvard Society of Fellows, Harvard Univ. 1977-1980. Faculty Positions: Faculty Fellow, Watson Institute for International Studies & Public Affairs, Brown University, March 2019 – present Ford Foundation Professor of Physics, Affiliate Professor -

RES0993.TXT (Word5)

Matthew J. Slaughter Tuck School of Business Tel: (603) 646-2939 Dartmouth College Fax: (603) 646-0995 100 Tuck Hall Email: [email protected] Hanover, NH 03755 Internet: www.dartmouth.edu/~mjs Current Positions Professor of International Economics, Tuck School of Business: 2007-present Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research: 2002-present Member, Conference on Research in Income and Wealth at NBER: 2006-present Senior Fellow for Business and Globalization, Council on Foreign Relations: 2007-present Board of Academic Advisors, International Tax Policy Forum: 2005-present Board of Academic Advisors, Tuck Center for Private Equity: 2005-present Past Positions Member, Council of Economic Advisers, Executive Office of the President: 2005-2007 Term Member, Council on Foreign Relations: 2000-2005 Visiting Fellow, Institute for International Economics: 1997-2005 Faculty Research Fellow, National Bureau of Economic Research: 1995-2002 Assistant and Associate Professor, Dartmouth College: 1994-2007 Panel Member, National Academy of Sciences: 2004-2005 Visiting Scholar: Federal Reserve System: 1998, 2002 International Monetary Fund: 1996, 1997 Consultant: World Bank: 1995-1997, 2000, 2002 Emergency Committee for American Trade: 1996-2003 National Foreign Trade Council: 2003 Committee for Fair International Taxation: 2004 Organization for International Investment: 2004 Board of Economists, Time Magazine: 2004 Education Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D. in Economics, 1994 University of Notre Dame, B.A. in Economics, summa cum laude, 1990 Fields of Interest The Economics and Politics of Globalization Publications in Journals "Does Inward Foreign Direct Investment Boost the Productivity of Domestic Firms?" with Jonathan E. Haskel and Sonia Pereira, Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 2007. -

Information, Physics, Quantum: the Search for Links

19 INFORMATION, PHYSICS, QUANTUM: THE SEARCH FOR LINKS John Archibald Wheeler * t Abstract This report reviews what quantum physics and information theory have to tell us about the age-old question, How come existence? No escape is evident from four conclusions: (1) The world cannot be a giant machine, ruled by any preestablished continuum physical law. (2) There is no such thing at the microscopic level as space or time or spacetime continuum. (3) The familiar probability function or functional, and wave equation or functional wave equation, of standard quantum theory provide mere continuum idealizations and by reason of this circumstance conceal the information-theoretic source from which they derive. (4) No element in the description of physics shows itself as closer to primordial than the elementary quantum phenomenon, that is, the elementary device-intermediated act of posing a yes-no physical question and eliciting an answer or, in brief, the elementary act of observer-participancy. Otherwise stated, every physical quantity, every it, derives its ultimate significance from bits, binary yes-or-no indications, a conclusion which we epitomize in the phrase, it from bit. 19.1 Quantum Physics Requires a New View of Reality Revolution in outlook though Kepler, Newton, and Einstein brought us [1-4], and still more startling the story of life [5-7] that evolution forced upon an unwilling world, the ultimate shock to preconceived ideas lies ahead, be it a decade hence, a century or a millenium. The overarching principle of 20th-century physics, -

Einstein and the Cultural Roots of Modern Science

Einstein and the Cultural Roots of Modern Science The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Holton, Gerald. Einstein and the cultural roots of modern science. In The Advancement of Science and Its Burdens, xiii-xlix. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998. Published Version http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674005303 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40508207 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Einstein and the cultura! roots of modern science The fruits of scientific research are nourished by many roots, inctuding the work of other scientists. Significantly, Albert Einstein himself char acterized his work as the "Maxwellian Program."* But often the imagi nation of scientists also draws on a quite different, "extrascientific" source. Indeed, in his own intellectual autobiography, Einstein asserted that reading David Hume and Ernst Mach had crucially aided in his early discoveries.^ Such hints point to one path that historical scholarship on Einstein, to this day, has hardly explored—tracing the main roots that may have helped shape his scientific ideas in the first place, for exam ple, the literary or philosophic aspect of the cultural milieu in which he and many of his fellow scientists grew up.^ To put the question more generally, as Erwin Schrodinger did in 1932., to what extent is the pursuit of science wzVzsMbsJzTigt, where the word hedzwgt can have the strict connective sense of "dependent on," the more gentle and useful meaning of "being conditioned by," or, as I prefer, "to be in reso nance with" ? In this Introduction I will explore how the cultural milieu in which Einstein found himself resonated with and conditioned his science. -

News and Notes

Journal of the Minnesota Academy of Science Volume 34 Number 1 Article 2 1967 News and Notes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/jmas Recommended Citation (1967). News and Notes. Journal of the Minnesota Academy of Science, Vol. 34 No.1, 3-8. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/jmas/vol34/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Minnesota Academy of Science by an authorized editor of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Report of Nominating Committee, 1967 Publicity ... ....... .. ........ Miss Jane Kolgcs Slate of Nominees Exhibit Space ...... ........... .. Robert Reitz /'resident Elect: * Meal Functions .......... .... .... Clarence Skar Richard Fulmer ........... .. .. ..... Cargill Faculty Hosts .. .. ............ ...... Co-chairmen Carl S. Miller .... .......... ... .. 3M Company Registration Information ..... .. Miss Jane Andrews Audio Visual .. .... .. ............. .. .. Clint Hall Secretary-Treasurer of the Academy':' Judging .. ... ... .... ... ......... Thur lo Thomas Eugene Gcnnarro ...... University of Minnesota Student Hosts ................. Miss Jane Andrews Richard Myshak ....... University of Minnesota Tours and Student Activities .. ... .. William McIntire /:"lect Two Directors - Industrial* -----•----- ( highest total vote receives four-year term second high -

Lebenslauf EF/NFP

Ernst Fehr DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF ZURICH UBS INTERNATIONAL CENTER OF ECONOMICS IN SOCIETY LABORATORY FOR SOCIAL AND NEURAL SYSTEMS RESEARCH Blümlisalpstr. 10 Tel. (41) (44) 634 37 01 CH-8006 Zürich Fax (41) (44) 634 49 07 ernst [dot] fehr [at] econ [dot] uzh [dot] ch Curriculum Vitae .................................................................................................... 2 Awards and Distinctions ........................................................................................ 5 Editorial Commitments and Duties......................................................................... 9 List of Publications ............................................................................................... 10 Books .............................................................................................................................................. 10 Selected Publications on Core Economic Topics ............................................................................. 10 Selected Publications in Evolutionary Economics and Psychology ................................................ 12 Selected Publications in Neuroeconomics ...................................................................................... 13 Other Publications in economics and psychology .......................................................................... 14 Other publications in Neuroeconomics .......................................................................................... 21 Republications ............................................................................................................................... -

VERNON L. SMITH Nobel Laureate in Economics 2002

VERNON L. SMITH Nobel Laureate in Economics 2002 Economic Science Institute Phone: 714.516.5480 Chapman University Fax: 714.628.2881 One University Drive [email protected] Orange, CA 92866 USA EDUCATION Ph.D. Harvard University 1955 M.A. University of Kansas 1952 B.S.E.E. California Institute of Technology 1949 EMPLOYMENT Professor of Economics and Law 2008-Present George L. Argyros Endowed Chair in Finance and Economics Chapman University Professor of Economics and Law 2001 – 2008 George Mason University Visiting Rasmuson Chair in Economics 2003-Present University of Alaska-Anchorage McClelland/Regents’ Professor of Economics 1998 - 2001 University of Arizona Hooker Distinguished Visiting Professor October 4 - 8, 1988 McMaster University Research Director 1986-2001 Economic Science Laboratory Professor of Economics 1975-2001 University of Arizona Visiting Professor 1974-1975 USC and Cal Tech Professor of Economics 1968-1975 University of Massachusetts 1 of 47 Professor of Economics 1967-1968 Brown University Professor/Krannert Outstanding Professorship 1961-1967 Purdue University Visiting Professor 1961-1962 Stanford University Associate Professor 1958-1961 Purdue University Assistant Professor 1955-1958 Purdue University Instructor of Economics 1951-1952 University of Kansas SERVICES/ ASSOCIATIONS Freelance Contributor Agreement 2018-Present The Wall Street Journal Editorial Leisure & The Arts, Book Pages Advisory Board Member 2018-Present Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University Board of Advisors 2018-Present Game -

Fall 2005 Newsletter

GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS COLLEGE August 2005 PHYSICS DEPARTMENT On-Campus Edition Gustavus Physics Radiations from Olin Hall Inside this issue: This annual newsletter offers highlights of the 2004-2005 academic year and Introducing Jim Miller 2 summer, news from current students, SPS and Student Awards 3 recent graduates and faculty, and infor- mation about the physics program for Faculty Activities 4-7 the year ahead. An online version with Visiting Speakers Program 7 color photos will be available at http://physics.gustavus.edu early in the Graduating Class of 2005 8-9 fall semester. Student Summer Research 10 In May, we bid farewell to the fifteen well as at universities and national labo- physics majors from the Class of 2005. ratories across the country. There was a Society of Physics Students 11 Graduates from this and recent classes new face around the department this First Decade Award 12 continue to pursue a variety of graduate summer. We welcomed Jim Miller, lab and professional degree programs and coordinator and computer support per- Study Abroad Possibilities 12 careers. May was also a sad time for us son on August 1. In addition to re- A Study Abroad Story 13 for another reason, the sudden death of search this summer, faculty traveled Jennings Ellis, lab coordinator, on May and attended conferences around the Nobel Conference 14 31. Jennings will be missed around the world. Faculty continue to assume Olin Observatory 15 department. Gustavus physics students leadership roles on campus and nation- participated in funded research with ally. (See subsequent columns and J-term 2005 Courses 16 faculty in Olin Hall this summer, as photos for these and other stories.) Research or Internships? 16 Fall Semester 2005 A. -

![Glenn T. Seaborg Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3848/glenn-t-seaborg-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-4933848.webp)

Glenn T. Seaborg Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Glenn T. Seaborg Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2000 Revised 2014 May Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006039 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89078514 Prepared by Margaret McAleer and Edward Green, Jr., with the assistance of Paul Colton, Alys Glaze, John Monagle, Susie Moody, Kathryn Sukites, and Chanté Wilson Collection Summary Title: Glenn T. Seaborg Papers Span Dates: 1866-1999 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1940-1998) ID No.: MSS78514 Creator: Seaborg, Glenn T. (Glenn Theodore), 1912-1999 Extent: 370,000 items ; 1,015 containers plus 1 oversize and 4 classified ; 407.4 linear feet ; 13 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Nuclear chemist, public official, and educator. Journals, correspondence, memoranda, minutes, reports, telephone and appointment logs, scientific research, speeches, writings, photographs, biographical material, newspaper clippings, and other printed matter documenting Seaborg's work as a nuclear chemist who codiscovered numerous chemical elements, as a professor of chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, California, and as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1961 to 1971. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Compton, Arthur Holly, 1892-1962--Correspondence.