The Dark Souls of Internationalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquisition De Deck13 Interactive, Un Des Principaux Studios De Développement Allemands Et Partenaire De Longue Date

COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE 25.06.2020 Acquisition de Deck13 Interactive, un des principaux studios de développement allemands et partenaire de longue date ▪ Première acquisition : une étape importante du plan stratégique EEE1 ▪ Contrôle de l'ensemble de la propriété intellectuelle ▪ Nouveau financement bancaire pour 46 millions d'euros PARIS, FRANCE – 25 Juin 2020 – FOCUS HOME INTERACTIVE (FR0012419307 ALFOC), l’un des leaders français de l’édition de jeux vidéo, annonce l'acquisition de 100% des actions composant le capital de la société de droit allemand Deck13 Interactive GmbH (« Deck13 »). Deck13 est un studio de développement de jeux allemand de premier plan et un partenaire de longue date de Focus Home Interactive. Deck13 emploie une équipe de 60 personnes hautement qualifiées et a développé plus de 20 jeux au cours des 18 dernières années. Deck13 a développé des succès majeurs tels que la franchise The Surge avec Focus Home Interactive et a réalisé un chiffre d'affaires de 5,5 millions d'euros au cours de l'année fiscale se terminant le 31 décembre 2019. Jürgen Goeldner, Président du Directoire, déclare : « Nous sommes très heureux d'accueillir les équipes de Deck13 et nous nous réjouissons de travailler ensemble pour atteindre nos objectifs ambitieux. Cette acquisition marque une étape importante dans notre histoire de croissance et renforcera notre modèle économique. Cette acquisition sera financée grâce au tirage d'une partie du nouveau financement bancaire de 46 millions d'euros qui alimentera également nos autres développements futurs ». Jan Klose, Directeur exécutif et co-fondateur de Deck13, ajoute : « Je suis ravi d'annoncer que Deck13 fait désormais partie de Focus Home Interactive. -

9 Rapport Spécial Des Commissaires Aux Comptes Sur Les Conventions

SOMMAIRE RAPPORT FINANCIER ANNUEL AU 31 MARS 2021 1. Introduction pages 5 à 9 2. Attestation de la personne responsable page 11 3. Rapport du Directoire pages 13 à 35 4. Rapport du Conseil de surveillance pages 37 à 45 5. Rapport des Commissaires aux comptes sur les comptes consolidés au 31 mars 2021 pages 47 à 50 6. Comptes consolidés pages 53 à 79 7. Rapport des Commissaires aux comptes sur les comptes annuels au 31 mars 2021 pages 81 à 84 8. Comptes annuels pages 87 à 107 9. Rapport des Commissaires aux comptes sur les conventions règlementées au 31 mars 2021 pages 109 à 112 RAPPORT DE RESPONSABILITÉ SOCIÉTALE DES ENTREPRISES (RSE) 10. Message du Président page 117 Intégrer la RSE aux activités de FHI pages 118 à 120 AXE 1 : Être un éditeur de jeux vidéo divertissants, sécurisants et respectueux pour nos joueurs pages 121 à 123 AXE 2 : Être un employeur attractif et responsable pages 123 à 126 Axe 3 : Être un éditeur au service de l’environnement et de la société pages 126 à 130 Note méthodologique/ A propos de ce rapport pages 130 à 131 Introduction 1 Message du Président MESSAGE DU PRESIDENT Cette année 2020-21 a été exceptionnelle d’un point de vue financier, puisque Focus a réalisé un Chiffre d’Affaires historique de 171M€ dans un contexte sanitaire extrêmement difficile. Nos équipes ont fait preuve d’une résilience, d’une motivation et d’un état d’esprit remarquables afin de continuer à délivrer des expériences uniques pour les joueurs. Les dispositions sanitaires et les conditions de télétravail mises en place pour nos collaborateurs ont ainsi permis de garder un haut niveau de performance, de service et de qualité. -

Cloud Gaming

Cloud Gaming Cristobal Barreto[0000-0002-0005-4880] [email protected] Universidad Cat´olicaNuestra Se~norade la Asunci´on Facultad de Ciencias y Tecnolog´ıa Asunci´on,Paraguay Resumen La nube es un fen´omeno que permite cambiar el modelo de negocios para ofrecer software a los clientes, permitiendo pasar de un modelo en el que se utiliza una licencia para instalar una versi´on"standalone"de alg´un programa o sistema a un modelo que permite ofrecer los mismos como un servicio basado en suscripci´on,a trav´esde alg´uncliente o simplemente el navegador web. A este modelo se le conoce como SaaS (siglas en ingles de Sofware as a Service que significa Software como un Servicio), muchas empresas optan por esta forma de ofrecer software y el mundo del gaming no se queda atr´as.De esta manera surge el GaaS (Gaming as a Servi- ce o Games as a Service que significa Juegos como Servicio), t´erminoque engloba tanto suscripciones o pases para adquirir acceso a librer´ıasde jue- gos, micro-transacciones, juegos en la nube (Cloud Gaming). Este trabajo de investigaci´onse trata de un estado del arte de los juegos en la nube, pasando por los principales modelos que se utilizan para su implementa- ci´ona los problemas que normalmente se presentan al implementarlos y soluciones que se utilizan para estos problemas. Palabras Clave: Cloud Gaming. GaaS. SaaS. Juegos en la nube 1 ´Indice 1. Introducci´on 4 2. Arquitectura 4 2.1. Juegos online . 5 2.2. RR-GaaS . 6 2.2.1. -

Half-Year Financial Report 2020-21

HALF-YEAR FINANCIAL REPORT 2020-21 1 CONTENTS Responsibility statement by the certifying officer…………………………………………….….page 3 Management report on the half-year financial statements 2020/21……………………………page 4 Half-year consolidated financial statements 2020/21……………………………………………page 11 2 Responsibility statement by the certifying officer for the half-year financial report 2020-21 I hereby certify that, to the best of my knowledge, the financial statements for the past six months presented in this half-year financial report have been prepared in accordance with the applicable accounting principles and give a true and fair presentation of the assets, liabilities, financial position and income of the company and all companies within the scope of consolidation. I further certify that the half-year management report presents a fair review of the significant events that occurred during the first six months of the financial year, their effect on the accounts, the principal transactions between related parties, as well as a description of the main risks and uncertainties for the remaining six months of the year. 3 FOCUS HOME INTERACTIVE Public limited company with Management Board and Supervisory Board with share capital of €6,395,630.40 Parc Pont de Flandre “Le Beauvaisis” - Bâtiment 28 11, Rue de Cambrai - 75019 Paris RCS Paris B 399 856 277 MANAGEMENT REPORT ON THE HALF-YEAR FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDING 31 MARCH 2021 1 April to 30 September 2020 In this document, “Focus Home Interactive” or “Company” refers to the French company registered in the Paris Trade and Companies Registry under number B 399 856 277. -

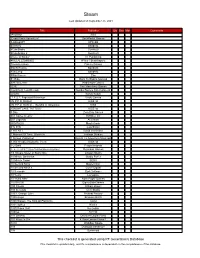

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Acquisition of Deck13 Interactive, a Leading German Game Development Studio and Long-Time Partner

PRESS RELEASE 25.06.2020 Acquisition of Deck13 Interactive, a leading German game development studio and long-time partner ▪ First studio acquisition: a major step in the Group’s EEE1 strategic plan ▪ Full ownership of Intellectual Property ▪ New bank financing of €46 million PARIS, FRANCE – 25th June 2020 – FOCUS HOME INTERACTIVE (FR0012419307 ALFOC), a leading French publisher of video games, announced the acquisition of 100% of share capital of Deck13 Interactive GmbH (“Deck13”), incorporated under German law. Deck13 Interactive is a leading German game development studio and long-time partner of Focus Home Interactive. Deck13 employs a team of 60 highly skilled workers and has developed over 20 games in the past 18 years. Deck13 Interactive has developed major successes such as The Surge franchise with Focus Home Interactive and achieved revenue of €5.5 million in the fiscal year ended 31st December 2019. Jürgen Goeldner, Chairman of the Management Board, declared: “We are very happy to welcome the team of Deck13 and look forward to working together to achieve our ambitious objectives. This acquisition marks a major milestone in our growth story and will strengthen our business model. This acquisition will be financed by the drawing down of the new bank financing of €46 million which will also support our other future developments”. Jan Klose, Managing Director and co-founder of Deck13, added: “I am delighted to announce that Deck13 is now part of Focus Home Interactive. Our companies have been working together successfully since 2011, developing award winning brands such as The Surge. We are looking forward to leveraging the incredible capabilities of Focus Home Interactive to develop new successes”.