Lithosphere Development in the Slave Craton: a Linked Crustal and Mantle Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Paleomagnetic Data from Precisely Dated Paleoproterozoic-Neoarchean Dikes in NE Fennoscandia, the Kola Peninsula

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-3423, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. New paleomagnetic data from precisely dated Paleoproterozoic-Neoarchean dikes in NE Fennoscandia, the Kola Peninsula Roman Veselovskiy (1,2), Alexander Samsonov (3), and Alexandra Stepanova (4) (1) Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Geological, Moscow, Russian Federation ([email protected]), (2) Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Geology, (3) Institute of Geology of Ore Deposits Petrography Mineralogy and Geochemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, (4) Institute of Geology, Karelian Research Centre RAS The validity and reliability of paleocontinental reconstructions depend on using multiple methods, but among these approaches the paleomagnetic method is particularly important. However, the potential of paleomagnetism for the Early Precambrian rocks is often dramatically restricted, primarily due to the partial or complete loss of the primary magnetic record during the rocks’ life, as well as because of difficulties with dating the characteristic magnetization. The Fennoscandian Shield is the best-exposed and well-studied crustal segment of the East European craton. The north-eastern part of the shield is composed of Archean crust, penetrated by Paleoproterozoic and Neoarchean mafic intrusions, mostly dikes. The Murmansk craton is a narrow (60-70 km in width) segment of the Archean crust traced along the Barents Sea coast of the Kola Peninsula for 600 km from Sredniy Peninsula to the east. At least five episodes of mafic magmatism of age 2.68, 2.50, 1.98, 1.86 and 0.38 Ga are distinguished in the Murmansk craton according to U-Pb baddeleyite and zircon dating results (Stepanova et al., 2018). -

Re-Evaluation of Strike-Slip Displacements Along and Bordering Nares Strait

Polarforschung 74 (1-3), 129 – 160, 2004 (erschienen 2006) In Search of the Wegener Fault: Re-Evaluation of Strike-Slip Displacements Along and Bordering Nares Strait by J. Christopher Harrison1 Abstract: A total of 28 geological-geophysical markers are identified that lich der Bache Peninsula und Linksseitenverschiebungen am Judge-Daly- relate to the question of strike slip motions along and bordering Nares Strait. Störungssystem (70 km) und schließlich die S-, später SW-gerichtete Eight of the twelve markers, located within the Phanerozoic orogen of Kompression des Sverdrup-Beckens (100 + 35 km). Die spätere Deformation Kennedy Channel – Robeson Channel region, permit between 65 and 75 km wird auf die Rotation (entgegen dem Uhrzeigersinn) und ausweichende West- of sinistral offset on the Judge Daly Fault System (JDFS). In contrast, eight of drift eines semi-rigiden nördlichen Ellesmere-Blocks während der Kollision nine markers located in Kane Basin, Smith Sound and northern Baffin Bay mit der Grönlandplatte zurückgeführt. indicate no lateral displacement at all. Especially convincing is evidence, presented by DAMASKE & OAKEY (2006), that at least one basic dyke of Neoproterozoic age extends across Smith Sound from Inglefield Land to inshore eastern Ellesmere Island without any recognizable strike slip offset. INTRODUCTION These results confirm that no major sinistral fault exists in southern Nares Strait. It is apparent to both earth scientists and the general public To account for the absence of a Wegener Fault in most parts of Nares Strait, that the shape of both coastlines and continental margins of the present paper would locate the late Paleocene-Eocene Greenland plate boundary on an interconnected system of faults that are 1) traced through western Greenland and eastern Arctic Canada provide for a Jones Sound in the south, 2) lie between the Eurekan Orogen and the Precam- satisfactory restoration of the opposing lands. -

A Mesoproterozoic Iron Formation PNAS PLUS

A Mesoproterozoic iron formation PNAS PLUS Donald E. Canfielda,b,1, Shuichang Zhanga, Huajian Wanga, Xiaomei Wanga, Wenzhi Zhaoa, Jin Sua, Christian J. Bjerrumc, Emma R. Haxenc, and Emma U. Hammarlundb,d aResearch Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, China National Petroleum Corporation, 100083 Beijing, China; bInstitute of Biology and Nordcee, University of Southern Denmark, 5230 Odense M, Denmark; cDepartment of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, Section of Geology, University of Copenhagen, 1350 Copenhagen, Denmark; and dTranslational Cancer Research, Lund University, 223 63 Lund, Sweden Contributed by Donald E. Canfield, February 21, 2018 (sent for review November 27, 2017; reviewed by Andreas Kappler and Kurt O. Konhauser) We describe a 1,400 million-year old (Ma) iron formation (IF) from Understanding the genesis of the Fe minerals in IFs is one step the Xiamaling Formation of the North China Craton. We estimate toward understanding the relationship between IFs and the this IF to have contained at least 520 gigatons of authigenic Fe, chemical and biological environment in which they formed. For comparable in size to many IFs of the Paleoproterozoic Era (2,500– example, the high Fe oxide content of many IFs (e.g., refs. 32, 34, 1,600 Ma). Therefore, substantial IFs formed in the time window and 35) is commonly explained by a reaction between oxygen and between 1,800 and 800 Ma, where they are generally believed to Fe(II) in the upper marine water column, with Fe(II) sourced have been absent. The Xiamaling IF is of exceptionally low thermal from the ocean depths. The oxygen could have come from ex- maturity, allowing the preservation of organic biomarkers and an change equilibrium with oxygen in the atmosphere or from ele- unprecedented view of iron-cycle dynamics during IF emplace- vated oxygen concentrations from cyanobacteria at the water- ment. -

A Sulfur Four-Isotope Signature of Paleoarchean Metabolism. K. W. Williford1,2, T

Astrobiology Science Conference 2015 (2015) 7275.pdf A sulfur four-isotope signature of Paleoarchean metabolism. K. W. Williford1,2, T. Ushikubo2,3, K. Sugitani4, K. Lepot2,5, K. Kitajima2, K. Mimura4, J. W. Valley2 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 USA 2WiscSIMS, Dept of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706 USA, 3Kochi Institute for Core Sample Research, JAMSTEC, Nankoku, Kochi, Japan 4Dept of Environmental Engineer- ing and Architecture, Nagoya University, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan, 5Université Lille Nord de France, Lille 1, La- boratoire Géosystèmes, CNRS UMR8217, 59655 Villeneuve d'Ascq, France. Introduction: When the disappearance of so (VCDT), and they are close to the origin on the Δ36S called “mass independent” fractionation of sulfur iso- vs. Δ33S plot, perhaps indicating a hydrothermal source topes (S-MIF) at ~2.4 Ga was first interpreted to indi- of sulfide decoupled from atmospheric interaction. cate pervasive atmospheric oxidation, a supporting Anhedral pyrite grains from the Anchor Ridge locality observation was the correlation between Δ36S and Δ33S show a similar lack of S-MIF and a very small range of with a slope of –0.9 that has come to be known as the δ34S (0 to –4‰), and may indicate a metasomatic “Archean array”[1]. The consistency of this relation overprint. Framboidal pyrite from the Waterfall Ridge through the Archean sulfur isotope record has been locality is better preserved and exhibits a heretofore interpreted to represent consistency in the atmospheric unreported range of sulfur four-isotopic compositions. process(es) responsible for generating S-MIF, and These pyrite grains vary between –2 and 10‰ in δ34S, conversely, slight shifts in slope (e.g. -

The Late Tectonic Evolution of the Slave Craton and Formation of Its Tectosphere

The Late Tectonic Evolution of the Slave Craton and Formation of its Tectosphere W.J. Davis, W. Bleeker, K. MacLachlan, Jones, A.G. and Snyder, D. An outstanding question in Archean tectonics is the relationship between thick, depleted lithospheric keels that presently underlie the cratons and the overlying crustal section. Evidence for Archean diamonds and Re-Os model ages of cratonic peridotites argue for the development of stable lithospheric mantle early in a cratons history, at least in part synchronous with crust formation or stabilisation (Pearson 1999). The late tectonic evolution of cratons is complex and involves extensive magmatism, deformation, and metamorphism that significantly post-date the timing of crust formation. Many of these tectonic events are difficult to reconcile with early development of thick tectosphere and suggest that crust-mantle coupling and stabilization occurred late in the orogenic development of cratons. Over the past decade the Slave craton in northwestern Laurentia, has emerged as a major diamondiferous craton. The extensive and well documented geological record of the Slave craton, provides a new crustal perspective on the development of diamond-bearing tectosphere. In this contribution we describe the late tectonic evolution of the Slave craton based on field and geochronological studies, supplemented by geochronological data from lower crustal xenoliths to argue that stabilisation of the cratonic root, certainly to depths of 200 km, was most likely a late feature of the craton. Geological Background The Slave is a small craton bounded by Paleoproterozic orogenic belts on its east and west. The craton is characterized throughout its central and western part by a Mesoarchean basement (4.0 -2.9Ga) referred to as the Central Slave Basement Complex (CSBC; Bleeker et al 1999), and its cover sequence, with isotopically juvenile (<2.85 Ga?) but undefined basement in the east (Thorpe et al 1992; Davis& Hegner, 1992; Davis et al. -

Geology of the Eoarchean, >3.95 Ga, Nulliak Supracrustal

ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ Geology of the Eoarchean, > 3.95 Ga, Nulliak supracrustal rocks in the Saglek Block, northern Labrador, Canada: The oldest geological evidence for plate tectonics Tsuyoshi Komiya, Shinji Yamamoto, Shogo Aoki, Yusuke Sawaki, Akira Ishikawa, Takayuki Tashiro, Keiko Koshida, Masanori Shimojo, Kazumasa Aoki, Kenneth D. Collerson PII: S0040-1951(15)00269-3 DOI: doi: 10.1016/j.tecto.2015.05.003 Reference: TECTO 126618 To appear in: Tectonophysics Received date: 30 December 2014 Revised date: 30 April 2015 Accepted date: 17 May 2015 Please cite this article as: Komiya, Tsuyoshi, Yamamoto, Shinji, Aoki, Shogo, Sawaki, Yusuke, Ishikawa, Akira, Tashiro, Takayuki, Koshida, Keiko, Shimojo, Masanori, Aoki, Kazumasa, Collerson, Kenneth D., Geology of the Eoarchean, > 3.95 Ga, Nulliak supracrustal rocks in the Saglek Block, northern Labrador, Canada: The oldest geological evidence for plate tectonics, Tectonophysics (2015), doi: 10.1016/j.tecto.2015.05.003 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Geology of the Eoarchean, >3.95 Ga, Nulliak supracrustal rocks in the Saglek Block, northern Labrador, Canada: The oldest geological evidence for plate tectonics Tsuyoshi Komiya1*, Shinji Yamamoto1, Shogo Aoki1, Yusuke Sawaki2, Akira Ishikawa1, Takayuki Tashiro1, Keiko Koshida1, Masanori Shimojo1, Kazumasa Aoki1 and Kenneth D. -

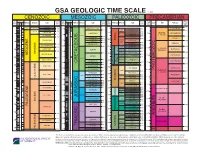

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

The Archean Geology of Montana

THE ARCHEAN GEOLOGY OF MONTANA David W. Mogk,1 Paul A. Mueller,2 and Darrell J. Henry3 1Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana 2Department of Geological Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana ABSTRACT in a subduction tectonic setting. Jackson (2005) char- acterized cratons as areas of thick, stable continental The Archean rocks in the northern Wyoming crust that have experienced little deformation over Province of Montana provide fundamental evidence long (Ga) periods of time. In the Wyoming Province, related to the evolution of the early Earth. This exten- the process of cratonization included the establishment sive record provides insight into some of the major, of a thick tectosphere (subcontinental mantle litho- unanswered questions of Earth history and Earth-sys- sphere). The thick, stable crust–lithosphere system tem processes: Crustal genesis—when and how did permitted deposition of mature, passive-margin-type the continental crust separate from the mantle? Crustal sediments immediately prior to and during a period of evolution—to what extent are Earth materials cycled tectonic quiescence from 3.1 to 2.9 Ga. These compo- from mantle to crust and back again? Continental sitionally mature sediments, together with subordinate growth—how do continents grow, vertically through mafi c rocks that could have been basaltic fl ows, char- magmatic accretion of plutons and volcanic rocks, acterize this period. A second major magmatic event laterally through tectonic accretion of crustal blocks generated the Beartooth–Bighorn magmatic zone assembled at continental margins, or both? Structural at ~2.9–2.8 Ga. -

01 Gslspecpub2020-155 1..14

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 1, 2021 Archean granitoids of India: windows into early Earth tectonics – an introduction SUKANTA DEY1* & JEAN-FRANÇOIS MOYEN2* 1Department of Earth Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, Mohanpur, Nadia 741 246, West Bengal, India 2Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, UJM-UCA-CNRS-IRD, Université de Lyon, 23 rue Dr Paul Michelon, 42023 Saint Etienne, France SD, 0000-0003-1334-8455 Present address: J-FM, School of Earth, Environment and Atmosphere Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia *Correspondence: SD, [email protected], [email protected]; J-FM, [email protected] Abstract: Granitoids form the dominant component of Archean cratons. They are generated by partial melting of diverse crustal and mantle sources and subsequent differentiation of the primary magmas, and are formed through a variety of geodynamic processes. Granitoids, therefore, are important archives for early Earth litho- spheric evolution. Peninsular India comprises five cratonic blocks bordered by mobile belts. The cratons that stabilized during the Paleoarchean–Mesoarchean (Singhbhum and Western Dharwar) recorded mostly diapir- ism or sagduction tectonics. Conversely, cratons that stabilized during the late Neoarchean (Eastern Dharwar, Bundelkhand, Bastar and Aravalli) show evidence consistent with terrane accretion–collision in a convergent setting. Thus, the Indian cratons provide testimony to a transition from a dominantly pre-plate tectonic regime in the Paleoarchean–Mesoarchean to a plate-tectonic-like regime in the late Neoarchean. Despite this diversity, all five cratons had a similar petrological evolution with a long period (250–850 myr) of episodic tonalite–trondh- jemite–granodiorite (TTG) magmatism followed by a shorter period (30–100 myr) of granitoid diversification (sanukitoid, K-rich anatectic granite and A-type granite) with signatures of input from both mantle and crust. -

2009 Geologic Time Scale Cenozoic Mesozoic Paleozoic Precambrian Magnetic Magnetic Bdy

2009 GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST. HIST. ANOM. ANOM. (Ma) CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 65.5 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 542 CALABRIAN MAASTRICHTIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE 1.8 31 C31 251 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 70.6 254 2A PIACENZIAN 32 C32 L 630 C2A 3.6 WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN 33 CAMPANIAN CAPITANIAN 5 C3 5.3 266 750 NEOPRO- CRYOGENIAN 80 C33 M WORDIAN MESSINIAN LATE 268 TEROZOIC 3A C3A 83.5 ROADIAN 7.2 SANTONIAN 271 85.8 KUNGURIAN 850 4 276 C4 CONIACIAN 280 4A 89.3 ARTINSKIAN TONIAN C4A L TORTONIAN 90 284 TURONIAN PERMIAN 10 5 93.5 E 1000 1000 C5 SAKMARIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 297 99.6 ASSELIAN STENIAN SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 299.0 5A 100 300 GZELIAN C5A 13.8 M KASIMOVIAN 304 1200 PENNSYL- 306 1250 15 5B LANGHIAN ALBIAN MOSCOVIAN MESOPRO- C5B VANIAN 312 ECTASIAN 5C 16.0 110 BASHKIRIAN TEROZOIC C5C 112 5D C5D MIOCENE 320 318 1400 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 326 6 C6 APTIAN 20 120 1500 CALYMMIAN E 20.4 6A C6A EARLY MISSIS- M0r 125 VISEAN 1600 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 SIPPIAN M3 BARREMIAN C6C 23.0 345 6C CRETACEOUS 130 M5 130 STATHERIAN CARBONIFEROUS TOURNAISIAN 7 C7 HAUTERIVIAN 1750 25 7A M10 C7A 136 359 8 C8 L CHATTIAN M12 VALANGINIAN 360 L 1800 140 M14 140 9 C9 M16 FAMENNIAN BERRIASIAN M18 PROTEROZOIC OROSIRIAN 10 C10 28.4 145.5 M20 2000 30 11 C11 TITHONIAN 374 PALEOPRO- 150 M22 2050 12 E RUPELIAN -

Evidence for Free Oxygen in the Neoarchean Ocean Based on Coupled Iron–Molybdenum Isotope Fractionation

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 86 (2012) 118–137 www.elsevier.com/locate/gca Evidence for free oxygen in the Neoarchean ocean based on coupled iron–molybdenum isotope fractionation Andrew D. Czaja a,b,⇑, Clark M. Johnson a,b, Eric E. Roden a,b, Brian L. Beard a,b, Andrea R. Voegelin c, Thomas F. Na¨gler c, Nicolas J. Beukes d, Martin Wille e a Department of Geoscience, 1215 W. Dayton Street, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA b NASA Astrobiology Institute, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA c Institut fu¨r Geologie, Universita¨t Bern, Baltzerstrasse 3, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland d Paleoproterozoic Mineralization Research Group, Department of Geology, University of Johannesburg, P.O. Box 524, Auckland Park, South Africa e Department of Geosciences, Universita¨tTu¨bingen, Wilhelmstraße 56, 72076 Tu¨bingen, Germany Received 16 December 2011; accepted in revised form 1 March 2012; available online 14 March 2012 Abstract Most geochemical proxies and models of atmospheric evolution suggest that the amount of free O2 in Earth’s atmosphere stayed below 10À5 present atmospheric level (PAL) until the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) that occurred between 2.2 and À1 À2 2.4 Ga, at which time free O2 in the atmosphere increased to approximately 10 to 10 PAL. Although photosynthetically produced “O2 oases” have been proposed for the photic zone of the oceans prior to the GOE, it has been difficult to constrain absolute O2 concentrations and fluxes in such paleoenvironments. Here we constrain free O2 levels in the photic zone of a Late Archean marine basin by the combined use of Fe and Mo isotope systematics of Ca–Mg carbonates and shales from the 2.68 to 2.50 Ga Campbellrand–Malmani carbonate platform of the Kaapvaal Craton in South Africa. -

PALEOMAP Paleodigital Elevation Models (Paleodems) for the Phanerozoic

PALEOMAP Paleodigital Elevation Models (PaleoDEMS) for the Phanerozoic by Christopher R. Scotese Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, 60202 cscotese @ gmail.com and Nicky Wright Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University [email protected] August 1, 2018 2 Abstract A paleo-digital elevation model (paleoDEM) is a digital representation of paleotopography and paleobathymetry that has been "reconstructed" back in time. This report describes how the 117 PALEOMAP paleoDEMS (see Supplementary Materials) were made and how they can be used to produce detailed paleogeographic maps. The geological time interval and the age of each paleoDEM is listed in Table 1. The paleoDEMS describe the changing distribution of deep oceans, shallow seas, lowlands, and mountainous regions during the last 540 million years (myr) at 5 myr intervals. Each paleoDEM is an estimate of the elevation of the land surface and depth of the ocean basins measured in meters (m) at a resolution of 1x1 degrees. The paleoDEMs are available in two formats: (1) a simple text file that lists the latitude, longitude and elevation of each grid point; and (2) as a netcdf file. The paleoDEMs have been used to produce: a set of paleogeographic maps for the Phanerozoic, a simulation of the Earth’s past climate and paleoceanography, animations of the paleogeographic history of the world’s oceans and continents, and an estimate of the changing area of land, mountains, shallow seas, and deep oceans through time. A complete set of the PALEOMAP PaleoDEMs can be downloaded at https://www.earthbyte.org/paleodem-resource-scotese-and-wright-2018/.