The End of Nature by B. Mckibben

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

PAF 2015 ENG.Indd

14th Festival of Film Animation 3–6 12 2015 Olomouc www.pifpaf.cz Catalogue PAF 2015 Acknowledgement: www.pifpaf.cz Danniela Arriado, Jiří Bartoník, Jana Bébarová, Petr Bilík, Petr Bielesz, Martin Blažíček, Michal Blažíček, Authors: Martin Búřil, Filip Cenek, Eva Červenková, Martin Čihák, Alexander Campaz, Martin Čihák, Eliška Děcká, David Katarína Gatialová, Marie Geierová, Vladimír Havlík, Helán, Miloš Henkrich, Alexandr Jančík, Tomáš Javůrek, Tamara Hegerová, Štěpánka Ištvánková, Jana Jedličková, Nela Klajbanová, Martin Mazanec, Marie Meixnerová, Alexandr Jeništa, Anna Jílková, Lucie Klevarová, Jiří Neděla, Jonatán Pastirčák,Tomáš Pospiszyl, Jakub Korda, Jana Koulová, Petr Krátký, Zdeňka Krpálková, Pavel Ryška, Matěj Strnad, Lenka Střeláková, Josef Kuba, Jiří Lach, Richard Loskot, Ondřej Molnár, Barbora Trnková, Veronika Zýková Hana Myslivečková, NAMU, Lenka Petráňová, Jan Piskač, Mari Rossavik, Radim Schubert, Kateřina Skočdopolová, Translators: Matěj Strnad, Barbora Ševčíková, Jan Šrámek, Petr Vlček, Magda Bělková, Nikola Dřímalová, Helena Fikerová, Kateřina Vojkůvková, FAMU Center for Audiovisual Studies, Václav Hruška, Karolina Chmielová, Jindřich Klimeš, Café Tungsram and Ondřej Pilát, Zuzana Řezníčková, Samuel Liška, Marie Meixnerová, Michaela Štaffová Audio-Video Department at the Faculty of Fine Arts of Brnu University of Technology, Department of Theatre and Film Editor: Studies at the Faculty of Arts of Palacký University Olomouc, Veronika Zýková The One Minutes, The University of J. E. Purkyně Czech proofreading: Festival -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

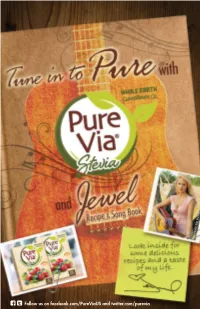

Jewel Is an Acclaimed American Singer, Songwriter, Actress, Poet, Painter, Philanthropist and Daughter to an Alaskan Cowboy Singer-Songwriter

WORLDWIDE SPEAKERS GROUP LLC YOUR GLOBAL PARTNER IN THOUGHT LEADERSHIP JEWEL Jewel is an acclaimed American singer, songwriter, actress, poet, painter, philanthropist and daughter to an Alaskan cowboy singer-songwriter. From the remote ranch of her Alaskan youth to the triumph of international stardom, the four-time Grammy nominee, hailed by the New York Times as a “songwriter bursting with talents” has enjoyed career longevity rare among her generation of artists. Her singular style and beauty continuously land her on the covers of such diverse magazines as TIME, People, Entertainment Weekly, Vanity Fair, In Style, Glamour and Seventeen. Stuff listed her among its “102 Sexiest Women in the World” while Blender went further, crowning her “rock’s sexiest poet.” Jewel launched her musical career early on, performing as a father-daughter act in Alaskan biker bars and lumberjack joints. Her solo career took off after she moved to San Diego, where she experienced moderate success in the folk-coffeehouse scene while living out of her car. Her first record, a deeply introspective, modern folk collection called Pieces of You, sold about 3,000 copies, nearly all in San Diego, in the nine months after its February 1995 debut. She then hit the road, touring with and opening for the likes of Bob Dylan, Merle Haggard, and Neil Young. She followed up her debut album with a succession of albums that steadily built her reputation and fan base: Spirit, This Way, and 0304. After a tremendous amount of success as a singer-songwriter and over 27 million albums sold, Jewel returned to her roots with the release of two country albums Perfectly Clear and Sweet and Wild. -

American Society of Plastic Surgeons Closes Loop on Breast Cancer

American Society of Plastic Surgeons Closes Loop on Breast Cancer During First BRA Day USA, October 17 Board-Certified Plastic Surgeons, Singer-Songwriter Jewel and Supporters Across the Country Unite to Educate Women about Breast Reconstruction FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 10, 2012 ARLINGTON HEIGHTS, Ill. – On October 17, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) and The Plastic Surgery Foundation (The PSF) will launch the first-ever Breast Reconstruction Awareness (BRA) Day USA, leading the charge to promote education, awareness and access to breast reconstruction following mastectomy or lumpectomy. The statistics are alarming: 7 out of 10 women eligible for breast reconstruction following cancer surgery are not being informed of their options. Studies have also revealed: Eighty-nine percent of women want to see what breast reconstruction surgery results would look like before undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Less than a quarter (23 percent) of women know the wide range of breast reconstruction options available. Only 22 percent of women are familiar with the quality of outcomes that can be expected. Only 19 percent of women understand that the timing of their treatment for breast cancer and the timing of their decision to undergo reconstruction greatly impacts their options and results. “We want to bring the topic of breast reconstruction into the larger breast cancer dialogue,” said ASPS President Malcolm Z. Roth, MD. “Letting women know their reconstruction options before or at the time of diagnosis is critically important to improving life after breast cancer. BRA Day USA is all about inspiring women who are on the road to recovery to a full life beyond breast cancer.” This year, the U.S. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

Exploring Racial Diversity in Caldecott Medal-Winning and Honor Books

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2016 Exploring Racial Diversity in Caldecott Medal-Winning and Honor Books Angela Christine Moffett San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Moffett, Angela Christine, "Exploring Racial Diversity in Caldecott Medal-Winning and Honor Books" (2016). Master's Theses. 4699. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.8khk-78uy https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4699 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING RACIAL DIVERSITY IN CALDECOTT MEDAL-WINNING AND HONOR BOOKS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Information Science San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Information Science by Angela Moffett May 2016 © 2016 Angela Moffett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled EXPLORING RACIAL DIVERSITY IN CALDECOTT MEDAL-WINNING AND HONOR BOOKS by Angela Moffett APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF INFORMATION SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2016 Dr. Joni Richards Bodart Department of Information Science Beth Wrenn-Estes Department of Information Science Nina Lindsay Oakland Public Library Abstract EXPLORING RACIAL DIVERSITY IN CALDECOTT MEDAL-WINNING AND HONOR BOOKS by Angela Moffett The Caldecott Medal, awarded annually by the American Library Association to the illustrator of the “most distinguished American picture book,” is the oldest and most prestigious award for children’s picture books in the United States. -

Follow Us on Facebook.Com/Pureviaus and Twitter.Com/Purevia

Follow us on facebook.com/PureViaUS and twitter.com/purevia Photo credit: Kurt Markus Live a Pure Life Jewel of Courtesy credit: Photo Me and my parents and siblings on the farm Growing up in Alaska, Photo credit: Courtesy of Jewel I experienced nature as it should be: fresh, Me and my son Kase on Mother’s Day simple, and pure. My family mainly lived off of the land, enjoying ripe summer berries and wild Discover a game of summer. Sweeter Side Lots of things have changed in my life since those Join me as I take you on a journey of discovering early days in Alaska. What hasn’t changed, however, recipes using Pure Via – and give you a peek into my is my belief that food should be as pure and close to life! I hope these recipes and tips inspire you to keep nature as possible. your cooking and your life simple – and a little Which is why I use Pure Via® more wholesome. in my favorite beverages as well as my cooking and These Pure Via packets fit perfectly in my guitar case, so I always know I have snacking because it makes them whenever I’m on the go! life just a little sweeter. Naturally. I’m really sweet on Project Clean Water, my nonprofit charity foundation that works to improve water quality in a sustainable way. So far, we’ve helped over 30 communities in 13 countries solve In the studio, working on my album, their drinking water problems. “Sweet and Wild” Visit http://www.jeweljk.com/cleanwater.html for more information. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M.