Part Eight Weighing Words and Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchism in Australia

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Australia Bob James Bob James Anarchism in Australia 2009 James, Bob. “Anarchism, Australia.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 105–108. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Gale eBooks (accessed June 22, 2021). usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 James, B. (Ed.) (1983) What is Communism? And Other Essays by JA Andrews. Prahran, Victoria: Libertarian Resources/ Backyard Press. James, B. (Ed.) (1986) Anarchism in Australia – An Anthology. Prepared for the Australian Anarchist Centennial Celebra- tion, Melbourne, May 1–4, in a limited edition. Melbourne: Bob James. James, B. (1986) Anarchism and State Violence in Sydney and Melbourne, 1886–1896. Melbourne: Bob James. Lane, E. (Jack Cade) (1939) Dawn to Dusk. N. P. William Brooks. Lane, W. (J. Miller) (1891/1980) Working Mans’Paradise. Syd- ney: Sydney University Press. 11 Legal Service and the Free Store movement; Digger, Living Day- lights, and Nation Review were important magazines to emerge from the ferment. With the major events of the 1960s and 1970s so heavily in- fluenced by overseas anarchists, local libertarians, in addition Contents to those mentioned, were able to generate sufficient strength “down under” to again attempt broad-scale, formal organiza- tion. In particular, Andrew Giles-Peters, an academic at La References And Suggested Readings . 10 Trobe University (Melbourne) fought to have local anarchists come to serious grips with Bakunin and Marxist politics within a Federation of Australian Anarchists format which produced a series of documents. Annual conferences that he, Brian Laver, Drew Hutton, and others organized in the early 1970s were sometimes disrupted by Spontaneists, including Peter McGre- gor, who went on to become a one-man team stirring many national and international issues. -

Forget Reaganreagan His Foreign Policy Was Right for His Time—Not Ours

Our Lousy Generals Immigration Reformed American Pravda Sex, Spies & the ’60s ANDREW J. BACEVICH WILLIAM W. CHIP RON UNZ CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD MAY/JUNE 2013 IDEAS OVER IDEOLOGY • PRINCIPLES OVER PARTY ForgetForget ReaganReagan His foreign policy was right for his time—not ours $9.99 US/Canada theamericanconservative.com Meet Pope Francis The Pope from the End of the Earth This lavishly illustrated volume by bestselling author Thomas J. Craughwell commemorates the election of Francis—first Pope from the New World—and explores in fascinating detail who he is and what his papacy will mean for the Church. • Forward by Cardinal Seán O’Malley. • Over 60 full-color photographs of Francis’s youth, priesthood and journey to Rome. • In-depth biography, from Francis’s birth and early years, to his mystical experience as a teen, to his ministry as priest and bishop with a heart for the poor and the unflagging courage to teach and defend the Faith. • Francis’s very first homilies as Pope. • Supplemental sections on Catholic beliefs, practices and traditions. $22.95 978-1-618-90136-1 • Hardcover • 176 pgs American Conservative Readers: Save $10 when you use coupon code TANGiftTAC at TANBooks.com. Special discount code expires 8/31/2013. Available at booksellers everywhere and at TANBooks.com e Publisher You Can Trust With Your Faith 58 THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE 1-800-437-5876MAY/JUNE 2013 Vol. 12, No. 3, May/June 2013 22 28 51 COVER STORY FRONT LINES ARTS & LETTERS 12 Reagan, Hawk or Dove? 7 Defense spending isn’t 40 The Generals: American The right foreign-policy lessons defense strength Military Command From to take from the 40th president WILLIAM S. -

Brilliant Creatures

A STUDY GUIDE BY PAULETTE GITTINS http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-471-4 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘They made us laugh, made us think, made us question, made us see Australia differently... are A two-part documentary By Director PAUL CLARKE and Executive Producers MARGIE BRYANT & ADAM KAY and Series Producer DAN GOLDBERG Written and presented by HOWARD JACOBSON SCREEN AUSTRALIA and 2014 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION THE ABC present a Serendipity and Mint Pictures production A STUDY GUIDE BY PAULETTE GITTINS 2 Introduction remarkable thing’ The story of the Australia they left in the sixties, and the impact they would have on the world stage is well worth reflecting on. Robert Hughes: firebrand art critic. Clive James: memoirist, broadcaster, poet. But why did they leave? What explains their spectacular success? Was it because they were Australian that they Barry Humphries: savage satirist. were able to conquer London and New York? And why does it matter so much to me? Germaine Greer: feminist, libertarian. asks our narrator. This is a deeply personal journey for Exiles from Australia, all of them. Howard Jacobson, an intrinsic character in this story. Aca- demic and Booker Prize winner, he reflects on his own ex- perience of Australia and how overwhelmed he was by the positive qualities he immediately sensed when he arrived ith these spare, impeccably chosen in this country. Why, he asks us, would Australians ever words, the voice-over of Howard Jacob- choose to exile themselves from such beauty and exhilara- son opens the BBC/ABC documentary tion? What were they sailing away to find? Brilliant Creatures and encapsulates the essence of four Australians who, having In wonderfully rich archive and musical sequences that Wsailed away from their native shores in the 1960’s, achieved reflect a fond ‘take’ on the era, director Paul Clarke has spectacular success in art criticism, literature, social cri- also juxtaposed interviews from past and present days. -

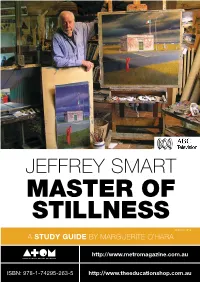

Jeffrey Smart Master of Stillness

JEFFREY SMART MASTER OF STILLNESS © ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY MArguerite o’hARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-263-5 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au I find it funny that perhaps in 100 years time, if people look at paintings done by the artists of this century, of our century, that the most ubiquitous things, like motor cars and television sets and telephones, don’t appear in any of the pictures. We should paint the things around us. Motor cars are very beautiful. I’m a great admirer of Giorgio Morandi; we all love Morandi, and he had all his props, his different bottles and his things. See, my props are petrol stations and trucks If a good painting comes off, it has a stillness, it has and it’s just the same a perfection, and that’s as great as anything that a thing. It’s a different musician or a poet can do. – Jeffrey Smart range of things. Introduction Jeffrey Smart Jeffrey Smart: Master of Stillness (Catherine Hunter, 2012) sheds light on the early influences of one of our greatest painters. Born in Adelaide in 1921, Smart’s early years were spent discovering the back lanes of the city’s inner suburbs. Now retired from painting, his last work Labyrinth (2011) evokes those memories. It is also a kind of arrival at the painting he was always chasing, never satisfied, hoping the next one on the easel would be the elusive masterpiece, the one that said it all. In this sense, Labyrinth brings a full stop to his career, and at the same time makes for a full, perpetual circle within his life. -

Far Right: Christopher Hitchens and Angela Gorgas in Paris in 1979, Angela Was Living in the City with Martin Amis, Who Was Writing Other People

Far right: Christopher Hitchens and Angela Gorgas in Paris in 1979, Angela was living in the city with Martin Amis, who was writing Other People Right: Martin Amis takes a break from writing to play the guitar in his cramped bachelor pad in Kensington Gardens Square in 1977 38 Memories Best friends BOYS AND GIRLS, ROMANCE AND BRO’MANCE Martin Amis and Christopher Hitchens discuss love, friendship and each other, while their fellow writer, Candia McWilliam, sums them both up hey face the camera with the Amschel Rothschild, the beautiful, gamin boy steady, unflinching gaze of the with the face like an El Greco portrait (pictured chosen; clever, beautiful and on page 41), hung himself in 1996 aged 41. rich, most of them, down from Adam Shand Kydd was found dead in Phnom Oxford and apparently with a life Penn in 2004, possibly from a drug overdose. of unbroken promise ahead of them. Yet Martin Tobias Rodgers, the antiquarian bookseller and Amis, baby-faced, brooding, and his friend, the notorious giver of parties to which “the famous, writer and polemicist Christopher Hitchens, the brilliant, the difficult and the unknown” each claim to have harboured a suspicion that were routinely invited, died in 1997. “He was they would “not only fail, but go under”. Neither helpless and somehow unhelpable,” his did of course, but the years have seen a terrible obituary noted. The writer Candia McWilliam, harvesting of some of their friends. photographed at 21 (overleaf), all long a 39 Candia McWilliam at the peak of her beauty in 1977. She became a successful novelist and winner of several literary accolades including the Betty Trask Award limbs and limpid eyes, is now blind, suffering a Philip, to a shop north of Piccadilly and bought bad patch with girls in the early 1970s, which condition called blepharospasm which means them each a gross of condoms. -

Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts Pdf

FREE CULTURAL AMNESIA: NECESSARY MEMORIES FROM HISTORY AND THE ARTS PDF Clive James | 912 pages | 17 Sep 2008 | WW Norton & Co | 9780393333541 | English | New York, United States Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts - Clive James - Google книги In an earlier era, commonplace books were what blogs and My Space pages are today. They were collections of quotations, observations, clippings, proverbs, poems, personal asides and anything else that someone found worthy of saving for future reference or sharing with friends. They served, W. At times Mr. Einstein is omitted though he makes an appearance in an essay on Chaplinbut his cousin, the musicologist Alfred Einstein, is accorded a chapter. As a critic, Mr. If the essays are heavily weighted toward artists and thinkers who lived in Vienna before the Anschluss, that is because Mr. In the most compelling entries in this volume, Mr. James uses his fecund talents as a writer and Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts to turn us on to the works of unfamiliar figures and to goad us to look at more famous personages from a new angle. He conjures up the aura of his subjects with a couple lines. Like most of Mr. In other cases Mr. In the end, one of the most valuable things about this volume is that Mr. James not only sends the reader in search of original texts written by or about his subjects, but also Cultural Amnesia: Necessary Memories from History and the Arts lots of other useful reading suggestions. On Vienna, there is Carl E. -

FINALISTS of the 58TH ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS (Listed in Alphabetical Order, by Last Name)

FINALISTS OF THE 58TH ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS (Listed in alphabetical order, by last name) A. JOURNALISTS OF THE YEAR A1. PRINT (Over 50,000 circulation) *Gary Baum, The Hollywood Reporter *Fred Dickey, San Diego Union Tribune *Dylan Howard, RadarOnline.com and The National ENQUIRER *Lacey Rose, The Hollywood Reporter *Jared Sichel, Jewish Journal A2. PRINT (Under 50,000 circulation) *Howard Fine, Los Angeles Business Journal *Eddie Kim, Los Angeles Downtown News *R. Scott Moxley, OC Weekly *Jon Regardie, Los Angeles Downtown News *Omar Shamout, Los Angeles Business Journal A3a. TELEVISION JOURNALIST *Mike Amor, 7 Network Australia *Norma Roque, KMEX *Derrick Shore, KCET *Antonio Valverde, KMEX A3b. RADIO JOURNALIST *Deepa Fernandes, KPCC *Warren Olney, KCRW *Stephanie O’Neill, KPCC *Susan Valot, Freelance A4. ONLINE JOURNALIST *Bill Boyarsky, Truthdig *Damien Newton, Streetsblog Los Angeles *Bill Raden, Capital & Main *Robert Scheer, Truthdig *Aitana Vargas, Freelance Correspondent A5. ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALIST *Randy Economy, AM 870 The Answer KRLA *Devra Maza, The Huffington Post *Daniel Miller, Los Angeles Times *Jim Rainey, Variety *Tom Teicholz, Forbes.com, Los Angeles Review of Books, Jewish Journal of LA A7. PHOTO JOURNALIST *Ringo Chiu, Los Angeles Business Journal *Francine Orr, Los Angeles Times *Ted Soqui, Freelance X. ALL MEDIA PLATFORMS X1. BEST HUMOR/SATIRE WRITING *Amy Alkon, Creators Syndicate, “Crowd Mary” *Amy Alkon, Creators Syndicate, “Requiem For A Scream” *Austin Bragg, Meredith Bragg and Andrew Heaton, Reason, “Star Wars Libertarian Special” *Jason Ruiz, Long Beach Post, “Long Beach Woman Detained for Sign Threatening Dihydrogen Monoxide (H2O) Attack, Cited for Illegal Posting” *Jaci Stephen, LA Not So Confidential, “Hello, Goodbye - for Adele” X2. -

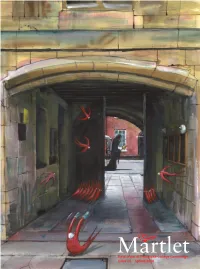

Newsletter of Pembroke College Cambridge Issue 24 Spring 2020 Challenges and Developments the Master, Lord Smith of Finsbury

Martlet Newsletter of Pembroke College Cambridge Issue 24 Spring 2020 Challenges and Developments The Master, Lord Smith of Finsbury Contents s our Director of Development Matthew Mellor always reminds me, within a year or so of 3 Community in APembroke’s foundation in 1347 we survived the Lockdown Black Death. And we’re still here, and flourishing, more 4 Pembroke’s Medieval than 670 years on. So for all the challenges that Manuscripts coronavirus and the traumas of Brexit and all sorts of other difficulty throw at us, we will carry on steadily doing 5 Snapshots of an what we are here to do: provide the very best education Aquaintance with for some of the brightest and best students. And to do so Clive James within a nurturing and supportive community that helps 6 Why Investors Might to welcome and sustain everyone. be Climate Allies: I started writing this before the full lockdown response to Covid-19 occurred, and since then our lives and our The Third Stage of students’ lives have been fundamentally (though we hope Corporate temporarily) changed. This term all teaching and all exams Governance is being done remotely, and the writing-up of dissertations 7 Re-evaluating our and preparation for exams will be rather different from Approach to the norm. But we will come through it all. And we can reflect on how, during the past term, our students have Treating Dementia been doing extraordinary things beyond the academic. 8 Pembroke Societies Our women’s first football team have won Cuppers for the before 1939 second time in a row – and appropriately, did so on the 9 Keep Faith day before International Women’s Day. -

Anarchism in Australia

Anarchism in Australia Bob James 2009 Contents References And Suggested Readings ............................ 6 2 At least as early as the 1840s (“Australia” having only been settled by white Europeans in 1788), the term “anarchist” was used as a slander by conservatives against their political opponents; for example, by W. C. Wentworth against Henry Parkes and J. D. Lang for speaking in favor of Aus- tralian independence from Britain. This opportunistic blackening of reputations has continued to the present day. What has also continued is that Australian attempts to express the philosophy positively have reflected other countries’ concerns or global rather than local issues. For example, the first positive public expression of the philosophy was the Melbourne Anar- chist Club (MAC) which, established in 1886, consciously reflected the Boston Anarchist Club’s approach to strategy and philosophy, having a secretary, a chairperson, speakers’ rules, and pre- pared papers which the public were invited to hear. The club was also a response to the 1884 call by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions of the US and Canada for a celebration of May 1, 1886 as an expression of working-class solidarity. The first MAC meeting was held on that day at the instigation of Fred Upham from Rhode Island, the two Australian-born Andrade brothers, David and William, and three other discontented members of the Australasian Secular Association (ASA) based in Melbourne. Australian labor activists had been involved in Eight Hour Day agitations since 1871 and in deliberately associating themselves with the overseas movement for May Day the MAC organiz- ers exposed their lack of involvement in local labor politics and their vulnerability to the rise or fall of distant agendas. -

Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love by James Booth Published 28Th

Philip Larkin: Life, Art and Love by James Booth Published 28 th August 2014 Publicist: Jamie Criswell [email protected]/ 020 7631 5761 / 07535979524 Reviews Literary Review, Review (Jeremy Noel-Tod) (14 August) Independent, Radar (Sean O'Brien) (16th August) Daily Telegraph, Review (Michael Deacon) (16th August) The Sunday Times, Review (John Walsh) (17th August) The Sunday Times News Review, News Feature, Dalya Alberge (17th August) Hull Daily Mail, Feature (18th August) Independent,Feature (22nd August) New Statesman, Review (Erica Wagner) (22nd August) Spectator, Review(Peter J. Conradi) (23rd August) The Times, Review (Philip Collins) (23rd August) Huddersfield Examiner, Review(Robert Sutcliffe) (23rd August) Mail on Sunday, Review (Francis Wheen) (24th August) Daily Mail, Review (Peter Lewis) (29th August) Irish Times, Review (David Wheatley) (30th August) The Observer, Review (Rachel Cooke) (31st August) The Sunday Telegraph, Review (Tim Stanley) (31st August) Financial Times, Review (Roger Lewis) (6th September) The Sunday Herald, Review (Russell Leadbetter) (5th September) London Magazine, Review (Terry Kelly) (Oct-Nov) The Yorkshire Post, Weekend Magazine, Interview (Yvette Huddleston) (5th September) Mantex, Review (John White) (9 September) About Larkin, 38, Review (Suzette Hill) (October) The Dish, Review (Alexander Adams) (20 October) Sydney Morning Herald, Review (Colin Steele) (31st October) London Review of Books, Review (Helen Vendler) (6th November) London Review of Books, Letter to the Editor (James Booth) -

THE HISTORY CHANNEL - TRIO: AMUNDSEN, Printing to Learn About Paper Money

Edward TelJcr. who helped develop the bomb; Paul Ni1Ze. who production of currency. Part 1. "What's it Worth." discusses what participated in the Strategic Bombing Survey, George Elsey. a sets the value of currency, how did money develop and how naval aide to Truman; Donald Russell. an aide to Secretary of money has changed over the centuries. Part 2. "It's as Gold," is State Arthur Byrnes; and other participants in the U.S.• Britain. all about gold and the value ofgold. Part 3. "Minting Money." Japan and Russia. takes you to the United States Mint in Philadelphia where you can watch the making ofaquarter. Part 4. "Printing Money," takes you to Washington DC to the Bureau ofEngraving and THE HISTORY CHANNEL - TRIO: AMUNDSEN, Printing to learn about paper money. Part 5, ''Money in Other SCOTT AND BYRD Countries," is about how currencies are made and used in other M-J,.H countries. ThursdJzy. August. 03, 9:00-10:00 am Exclusive expeditionary scenes and actual recordings TLC - TLC ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: MONEY: chronicle the dramatic stories ofthese Arctic explorers. KIDS AND CASH: MONEY AND YOU K-3.~,SM l1li Tuesday, September. 12, 4:00-5:00 am Tuesday, October, 17, 4:00-5:00 am TLC - OFF-AIR TAPING Tuesday, November, 21. 4:00-5:00 am Tuesday, December. 26. 4:00-5:00 am Educators will be able to videotape "TLC Elementary School." the new commercial-free series and use up to two years This five part series profiles finance. youth and the entrepre from the last date the programs airs. -

New York Times Columnist Frank Rich Will Speak At

For Immediate Release: CONTACT: Doug Gavel February 27, 2012 HKS Communications (617) 495-1115 Alan Rusbridger, editor of the Guardian to receive Goldsmith Career Award for Excellence in Journalism CAMBRIDGE, MA – Alan Rusbridger, editor of the British-based Guardian newspaper, will address an audience of students, faculty, journalists and members of the public on Tuesday, March 6 at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. The program begins at 6 p.m. in the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum, 79 JFK Street, Cambridge, and is sponsored by the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy. Rusbridger will receive the Goldsmith Career Award for Excellence in Journalism in recognition of his leadership in the Guardian’s five-year investigation and exposure of phone hacking by employees of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. He also led the Guardian’s negotiations with Julian Assange and subsequent publication of WikiLeaks documents. Rusbridger has been instrumental in the Guardian’s “digital-first” business strategy. Alan Rusbridger has been editor of the Guardian since 1995. He is editor-in-chief of Guardian News & Media, a member of the GNM and GMG Boards and a member of the Scott Trust, which owns the Guardian and the Observer. Rusbridger’s career began at the Cambridge Evening News, where he trained as a reporter before first joining the Guardian in 1979. He worked as a general reporter, feature writer and diary columnist before leaving to succeed Clive James and Julian Barnes as the Observer’s TV critic. In 1987, he worked as the Washington correspondent for the London Daily News before returning to the Guardian as a feature writer.