Front Matter Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tollygunge Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-152-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-827-8 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 167 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Ward-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Ward by Population Size | 11-12 Sex Ratio (Total & 0-6 Years) | Religious -

THIS DEED of CONVEYANCE Is Made on This TH Day of November Two Thousand and Nineteen

THIS DEED OF CONVEYANCE is made on this TH Day of November Two Thousand and Nineteen BETWEEN 1 ROYALVISION CONSTRUCTION PVT.LTD (having PAN- AAGCR5126H). a private Ltd. Company having its Registered office at 7A, Bentick Street, 1st Floor, Room No-103, P.O. Hare Street, P.S - Hare Street ,Kolkata-700001 represented by its Directors and Authorized Signatory namely (1) SRI. SIDDARTHA GUPTA (having PAN- ADTPG6034E) s/o SUBHAS CHANDRA GUPTA by occupation Service, by faith - Hindu, by nationality Indian, residing at 10 Swami Vivekananda Road, Flat No-5D, near Diamond City North, Nager Bazar P.S – South Dumdum, Kolkata- 700074 and (2) SMT. VINITA AGARWAL (having PAN- ADKPA9449A) w/o Sri. Vishnu Agarwal, by faith Hindu, by occupation- Business ,by Nationality -Indian, residing at 33,Rash Behari Avenue, P.O. Kalighat, P.S.Tollygunge, Kolkata-700026 herein after called and referred to as the OWNERS (which expression shall unless excluded by or repugnant to the context be deemed to mean and include their heirs, successors -in-office, executors, administrators, legal representatives attornies and assigns) of the ONE PART as Land Owners. AND ALMOUR CONSTRUCTION (having PAN -ABJFA2812L) a registered Partnership firm having Its place of business at 12, Russa Road (East) 2nd Lane presently known as Chinmoy Chattopadhyay Sarani, 1st floor, P.O. Tollygunge, P.S. Charu Market, Kolkata- 700033, being represented by its Partners 1) SMT. SHIKHA MODANI (having PAN- AEJPM1038D) w/o Sri Sanjay Modani, by faith Hindu, by occupation-Business, by Nationality-Indian, residing at 137,S.P Mukherjee Road, Flat No-3D, Kolkata- 700026. -

A List of Terminated Vendors As on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner

A List of Terminated Vendors as on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner Name Address City Reason for Termination 1 124475 Excel Associates 123 Infocity Mall 1 Infocity Gandhinagar Sarkhej Highway , Gandhinagar Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 2 125073 Karnavati Associates 303, Jeet Complex, Nr.Girish Cold Drink, Off.C.G.Road, Navrangpura Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 3 132097 Sam Agency 29, 1St Floor, K B Commercial Center, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380001 Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 4 124284 Raza Enterprises Shopno 2 Hira Mohan Sankul Near Bus Stand Pimpalgaon Basvant Taluka Niphad District Nashik Ahmednagar Fraud Termination 5 124306 Shri Navdurga Services Millennium Tower Bldg No. A/5 Th Flra-201 Atharva Bldg Near S.T Stand Brahmin Ali, Alibag Dist Raigad 402201. Alibag Breach Of Contract 6 131095 Sharma Associates 655,Kot Atma Singh,B/S P.O. Hide Market, Amritsar Amritsar Breach Of Contract 7 124227 Aarambh Enterprises Shop.No 24, Jethliya Towars,Gulmandi, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 8 124231 Majestic Enterprises Shop .No.3, Khaled Tower,Kat Kat Gate, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 9 125094 Chudamani Multiservices Plot No.16, """"Vijayottam Niwas"" Aurangabad Breach Of Contract 10 NA Aditya Solutions No.2239/B,9Th Main, E Block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, Karnataka -560010 Bangalore Fraud Termination 11 125608 Sgv Associates #90/3 Mask Road,Opp.Uco Bank,Frazer Town,Bangalore Bangalore Fraud Termination 12 130755 C.S Enterprises #31, 5Th A Cross, 3Rd Block, Nandini Layout, Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 13 NA Sanforce 3/3, 66Th Cross,5Th Block, Rajajinagar,Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 14 132890 Manasa Enterprises No-237, 2Nd Floor, 5Th Main First Stage, Khb Colony, Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079 Bangalore Breach Of Contract 15 177367 Bharat Associates 243 Shivbihar Colony Near Arjun Ki Dairy Bankhana Bareilly Bareilly Breach Of Contract 16 132878 Nuton Smarte Service 102, Yogiraj Apt, 45/B,Nutan Bharat Society,Opp. -

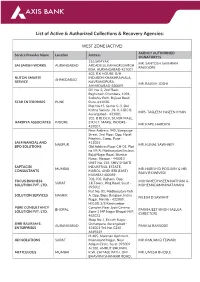

List of Active & Authorized Collections & Recovery Agencies

List of Active & Authorized Collections & Recovery Agencies: WEST ZONE (ACTIVE) AGENCY AUTHORISED Service Provider Name Location Address SIGNATORY/S 256,SAMYAK MR. SANTOSH SAKHRAM SAI SAKSHI WORKS AURANGABAD ARCADE,ULKANAGRI,GARGH RAJEGORE EDA, AURANGABAD-431001 402, R.K HOUSE, B/H NUTON SMARTE INDUBEN KHAKHRAWALA, AHMEDABAD SERVICE NAVRANGPURA, MR. RAJESH JOSHI AHMEDABAD-380009. Off No. 2, 2nd Floor, Raghunath Chambers, 1094, Sadashiv Peth, Bajirao Road, STAR ENTERPRISES PUNE Pune-411030. Plot No.15, Sector C-3, Shri Krihna Society , N- 8, CIDCO, MRS. TASLEEM YASEEN KHAN Aurangabad - 431001. 203, B BLOCK, SILVER MALL, HARDIYA ASSOCIATES INDORE 8 R.N.T. MARG, INDORE- MR. KAPIL HARDIYA 452001. New Address: 940, Sinegauge Street, 2nd Floor, Opp. Hotel Megistic, Camp, Pune - SAI FINANCIAL AND 411001 NAGPUR MR. KUNAL SAWHNEY BPO SOLUTIONS Old Address:Floor-CH-01, Plot no 59/A, Madhusudan Enclave, Bajaj Nagar Road, Shankar Nagar, Nagpur - 440010 UNIT No. 158, SHIV SHAKTI SAPTAGIRI INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, MUMBAI MR. HARISH D POOJARY & MR. CONSULTANTS MAROL, ANDHERI (EAST), RAJIV R DWIVEDI MUMBAI-400059. 702-703, Rajhans, Opp. FOCUS BUSINESS MOHAMEDYASEEN NATHANI & SURAT J.K.Tower, Ring Road, Surat - SOLUTION PVT. LTD. MOHEMADAMIN NATAHANI 395002 Flat No. 01, Madhusudan Park SOLUTION SERVICES NASHIK A, Opp. Bapu Banglow, Indira NILESH D SAWANT Nagar, Nashik - 422009. HIG (B) 1/8 Ranthambor PURE CONSULTANCY Complex Near Jyoti Cinema BHOPAL PARAMJEET SINGH SALUJA SOLUTION PVT. LTD. Zone-1 MP Nagar Bhopal-M.P. (DIRECTOR) 462023 Shop No 1, Eknath Nagar, SHRI BALIRAM'S Osmanpura, Aurangabad - AURANGABAD PANKAJ BANSODE ENTERPRISES 431001 Tel. No. 0240 6649819 H-405, Manthan Aprtment, ADI SOLUTIONS SURAT Muktanand Nagar, Near MR. -

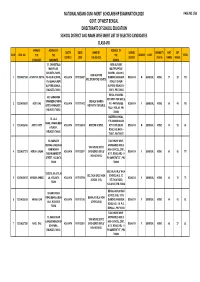

Kolkata Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/63 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL 7/1, CHANDITALA NEW ALIPORE MAIN ROAD, MULTIPURPOSE KOLKATA-700053, SCHOOL, 23A/439/1, NEW ALIPORE 1 123204307048 ACHINTYA DUTTA PO- NEW ALIPORE, KOLKATA 19170108427 DIAMOND HARBOUR KOLKATA M GENERAL NONE 57 53 110 MULTIPURPOSE SCHOOL PS- BEHALA,NEW ROAD, P.O-NEW ALIPORE,BEHALA , ALIPORE, KOLKATA - KOLKATA 700053 700073, PIN-700053 BEHALA SHARDA 6/D, SARADAMA VIDYAPITH FOR GIRLS, UPANIBESH,PARNA BEHALA SHARDA 2 123204306005 ADITI DAS KOLKATA 19170113412 PO - PARNASREE KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 60 49 109 SREE,PARNASREE , VIDYAPITH FOR GIRLS PALLY, KOL-60, PIN- KOLKATA 700060 700060 MODERN SCHOOL, TILJALA 17B, MANORANJAN ROAD,TANGRA,BENI 3 123204306180 ADITYA ROY KOLKATA 19170106510 MODERN SCHOOL ROY CHOUDHURI KOLKATA M GENERAL NONE 54 35 89 A PUKUR , ROAD, KOLKATA - KOLKATA 700046 700017, PIN-700017 3A RAMNATH TAKI HOUSE GOVT. BISWAS LANE,RAJA SPONSORED GIRLS' TAKI HOUSE GOVT. RAM MOHAN HIGH SCHOOL, 299C, 4 123204307075 ADRIJA BASAK KOLKATA 19170103911 SPONSORED GIRLS' KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 61 56 117 SARANI,AMHERST A.P.C. ROAD, KOL - 9 HIGH SCHOOL STREET , KOLKATA PO AMHERST ST., PIN- 700009 700009 BELTALA GIRLS' HIGH 30/25,TILJALA,TILJA BELTALA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (H.S), 17, 5 123204306135 AFREEN AHMED LA , KOLKATA KOLKATA 19170107506 KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 44 31 75 SCHOOL (H.S) BELTALA ROAD, 700039 KALIGHAT, PIN-700026 BEHALA GIRLS HIGH 30 BARIK PARA SCHOOL(H.S), 337/4, ROAD,BEHALA,BEH BEHALA GIRLS HIGH 6 123204306129 AHANA DAS KOLKATA 19170112202 DIAMOND HARBOUR KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 49 43 92 ALA , KOLKATA SCHOOL(H.S) ROAD, KOL - 34 P.O. -

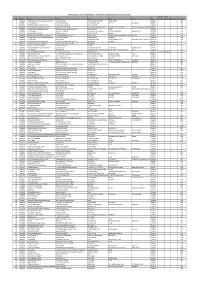

Share Liable to Be Transferres to IEPF Lying in UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT

SHARES LIABLE TO BE TRANSFERRED TO IEPF LYING IN UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT Second Third S.No Folio Name Add1 Add2 Add3 Add4 PIN Holder Holder Delivery Shares 1 000010 HARENDRA KUMAR MAGANLAL MEHTA C/O SHRINAGAR 1198 CHANDNI CHOWK DELHI 110006 110006 0 480 2 000013 N S SUNDARAM 9B CLEMENS ROAD POST BOX NO 480 VEPERY CHENNAI 7 600007 0 210 3 000024 BABUBHAI RANCHHODLAL SHAH 153-D KAMLA NAGAR, DELHI-110 007. 110007 0 210 4 000036 CHANDRAKANT RAOJIBHIA AMIN M/S APAJI AMIN & CO CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS 1299/B/1 LAL DARWAJA NEAR DR K M SHAH S HOSPITAL380001 0 615 5 000042 CHAMPAKLAL ISHWARLAL SHAH 2/4456 SHIVDAS ZAVERZIS SORRI SAGRAMPARA SURAT 395002 0 7 6 000048 K V SIVANNA 181/50 4TH CROSS VYALIKAVAL EXTENSION P O MALLESWARAM BANGALORE 3 560003 0 210 7 000052 NARAYANDAS K DAGA KRISHNA MAHAL MARINE DRIVE MUMBAI 1 400001 0 210 8 000080 MANGALACHERIL SAMUEL ABRAHAM AVT RUBBER PRODUCTS LTD PLOT NO 14-C COCHIN EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE COCHIN 682030 0 502 9 000089 RAMASWAMY PILLAI RAMACHANDRAN 1 PATULLOS ROAD MOUNT ROAD CHENNAI 2 600002 0 435 10 000134 P A ANTONY JOSEALAYAM MUNDAKAPADAM P O ATHIRAMPUZHA DIST-KOTTAYAM KERALA STATE686562 0 210 11 000168 S KOTHANDA RAMAN NAYANAR 11 MADHAVA PERUMAL KOVIL ST MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600004 0 435 12 000171 JETHALAL PANJALAL PAREKH D K ARTS &SCIENCE COLLEGE JAMNAGAR 361001 0 67 13 000173 SAJINI TULSIDAS DASWANI 24 KAHUN ROAD POONA 1 411001 0 1510 14 000226 KRISHNAMOORTY VENNELAGANTI HEAD CASHIER STATE BANK OF INDIA P O GUDUR DIST NELLORE 524101 0 435 15 000227 HAR PRASAD PROPRIETOR M/S GORDHAN DASS SHEONARAINKATRA -

Tata Starbucks Enters Kolkata with Three New Stores

Tata Starbucks Enters Kolkata With Three New Stores KOLKATA, India; March 20, 2018 - Tata Starbucks Private Limited, the 50/50 joint venture between Starbucks Coffee Company (Nasdaq: SBUX) and Tata Global Beverages Limited, will welcome its customers in Kolkata for the first time on March 21. Delivering the iconic ‘Third Place’ experience to customers and stewarding the company’s commitment to the city, Tata Starbucks will open three stores, marking the seventh city for the company in India. Sumitro Ghosh, chief executive officer, Tata Starbucks said, “We are honored to bring Starbucks to Kolkata, a city that has always been known for its cultural heritage and grandeur. Our aspiration is to delight our customers in Kolkata with the unique Starbucks Experience that is built on three core fundamentals – our partners (employees), our stores and our coffee. The institution of the ‘adda’ and the timeless passion it invokes in those who know of the city of Kolkata is inspiring. We hope to pay homage to the city’s inherent tradition by becoming a new ‘adda’ for our customers in Kolkata.” The three stores have been designed to weave Starbucks heritage and coffee passion into the vibrant and colorful culture of Kolkata. The regional craftsmanship, handmade by local artists and designers, brings this narrative to life across the city with different elements emphasized at each store. The Starbucks flagship store, located inside the iconic 108 year old Park Mansions on Park Street, celebrates Starbucks brand heritage with a large depiction of the Starbucks Siren, created with local tapestry, in the many colors found on the streets of Kolkata. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English ISSN: 0976-8165

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal In English ISSN: 0976-8165 The Refugee Settlements in ‘Calcutta’ and the Changes in the Refugee Colonies of ‘Kolkata’ Arunita Samaddar Research Scholar, Jadavpur University. Abstract: The partition of the Indian subcontinent not only killed thousands of people, but also uprooted and displaced millions from their traditional homeland – their ‘desher maati’. The severance of India’s unity, which has been described as the ground-breaking incident of reconfiguration of this nation, did not simply break the bonds between people or create territorial splits, but also partition of neighbourhoods, villages and cities. Gradually it caused rift between communitiesand families who had lived in harmony. In Bengal, the trauma of this divide reshaped the entire outlook. This paper traces how along with strong economic implications the act of Partition had a deep psychological impact on the settlers in an out of Bengal. Keywords: partition, Indian subcontinent, Bengal, economic implications. “the geography of partition is not that of a mountain amid plains, but of a thousand plateaus.”1 The recapturing of that schizophrenic moment of the partition of India is a daunting task, fraught with complexity, given the much-contested nature of ‘post-colonial’ subject. Thus the formation, rather the transformation of any city, especially Calcutta (now Kolkata), is mirrored in the multifaceted activities that surrounded the brink of colonialism and the onset of post-colonial era.2 The city of Calcutta was admittedly a social product and an economic construct, and as such it was brought into being by forces external to it. -

Disaster Management

ACTION PLAN TO MITIGATE FLOOD, CYCLONE & WATER LOGGING 2017 THE KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 1 2 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INCLUDING ACTION PLANS ARE MENTIONED UNDER FOLLOWING HEADS Sl No Item Page A Disaster Management – Introduction 5 B Important Activities of KMC in 11 connection with the Disaster Management C Major Water Logging Pockets 15 D Deployment of KMC Mazdoor at Major 29 Water Logging Pockets E Arrangement all Parks & Square 39 Development required removal of uprooting trees trimining at trees F List of the Sewerage and Drainage 45 Pumping Stations and deployment of temporary portable pumps during monsoon G Emergency arrangement during the 77 ensuing Nor’wester/Rainy season in the next few months of 2017 (Mpl. Commr. Circular No 11 of 2017-18 Dated 06/05/2017) H List of the roads where cleaning of G. 97 Ps. mouths /sweeping of roads will be made twice in a day by S.W.M. Department I Essential Telephone Numbers 107 3 4 A. DISASTER MANAGEMENT – INTRODUCTION The total area under Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) is about 204.75 Sq. Km. which is divided into 16 Boroughs from Ward No-1 to Ward No- 144. The total population of the KMC area as per 2001 Census is about 4.6 million. Moreover, the floating population of the city is about 6 million. They are coming to this city for their livelihood from the outskirt and suburbs of the city of Kolkata i.e. City of Joy. From the experience regarding the water logging/flood condition during rainy season for the last few years, the KMC authority felt to publicize the disaster management plan as well as disaster management system for the benefit of the citizens, local representatives, State Govt. -

Ward No: 093 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 093 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 140(MOLLAHATI)P.A. SHAH RD. AAN HALDAR LATE PATIPABAN HALDAR 1 1 2 1 2 MOLLAHHATI 126 P.A.S RD ABHIJIT DAS LT PRANPALLAV DAS 2 2 4 2 3 19(DASNAGAR COLONY)GOBINDAPUR ABU SARKAR LATE D. SARKAR 3 1 4 4 4 GOBINDAPUR 52 GOBINDAPUR ROAD KOL 45 ADHIR HALDER LT AMBIK HALDER 2 2 4 5 5 8E ROHIM OSTAGER ROAD ADHIR NASKAR G. NASKAR 1 1 2 6 6 MOJIT PARA 96 PRINCE ANWAR SHAH ROAD ADKHIR CH MONDAL KRISHNA PADA MONDAL 4 3 7 7 7 80 P. A. SHAH ROAD AHAMED GARI S. MONDOL 1 3 4 8 8 3NO RAIL GATE GOBINDA PUR ROAD AJAY PATRA SUDHARNA PATRA 3 1 4 9 9 156 P.G.H. SHAH ROAD AJAY SAHA RAJANDRA SAHA 3 1 4 10 10 2 RAHIM OSTAGAR ROAD AJIT MANDAL SREEDHAR MANDAL 3 2 5 11 11 MOLLAHATI 140 PRINCE ANWAR SHAH ROAD AJIT MONDAL LT. LAL MOHAN MONDAL 2 1 3 12 12 126 P. A. SHAH RD. AJIT NASKAR LATE F. C. NASKAR 2 2 4 13 13 52 GOBINDAPUR ROAD AJIT PARAMANIK RATI KANTA PARAMANIK 2 2 4 14 14 11A ROHIM OSTAGAR ROAD AJOY DAS LATE J. DAS 3 3 6 15 15 94 P.G.MD. SHAH RD. AJOY KAYAL A. P. KAYAL 1 3 4 16 16 52 GOBINDAPUR ROAD AJOY PATRA SUDDNA PATRA 3 1 4 17 17 52 GOBINDAPUR ROAD AKADASI JALENI LATE GAGADHAR JALENI 2 3 5 18 18 F/28 KATJUNAGAR AKHOY DAS SATHEN CHARAN DAS 2 1 3 19 19 31(C.I.T SCHEME) P. -

Store Locations

Store Locations City Store Name Locality Ahemdabad Law Garden Cross Words Ahemdabad Prahalad nagar Toy Zapp/Toy Cra Ahemdabad CG Road Kavita Toys Ahmedabad Hamleys ALPHA ONE AHMEDABAD Ahmedabad Landmark Abhijeet V AHM Law Garden Ahmedabad Shoppers Stop ALPHA AHMEDABAD Ahmedabad Shoppers Stop CG ROAD AHMEDABAD Amritsar Hamleys MALL OF AMRITSAR Amritsar Shoppers Stop AMRITSAR Aurangabad Shoppers Stop AURANGABAD Bangalore ToysRus Toys R us, Phoenix Marketcity, Bangalore Bangalore ToysRus Toys R us, Vegacity, Bangalore Bangalore Hamleys PHOENIX MARKET CITY BANGALORE Bangalore Hamleys LIDO 1MG ROAD MALL BANGALORE Bangalore Landmark Brigade Orion Mall Bangalore Bangalore ToysRus Phoenix Marketcity Bangalore Landmark Forum Mall BNG Koramangala Bangalore Hamleys MANTRI-MALL-BANGALORE Bangalore ToysRus Vegacity Bangalore Hamleys VR MALL BANGALORE Bangalore Shoppers Stop BENRGATTA Bangalore Shoppers Stop WHITEFIELD INORBIT BNG Bangalore Shoppers Stop SOUL SPACE BANGALORE Bangalore Shoppers Stop GARUDA Bangalore Landmark CMJ BLDG BNG Kamraj Road Bangalore Shoppers Stop MANTRI MALLESWARAM Bangalore Shoppers Stop OLD MADRAS BNG Bangalore Shoppers Stop KORAMANGALA Bangalore Shoppers Stop WHITEFIELD Bangalore Banshri Evergreen Toys Bangalore Bllundre Peekaboo / Baby Desire Bangalore HSR layout Kids Giggle / Baby Desire / Baby Outlet Bangalore Commercial Street Toy World Bangalore Frazer Town Dream World Bangalore HBR Layout Toy Junction Bhopal Hamleys DB CITY MALL BHOPAL Bhopal Shoppers Stop BHOPAL Bhubaneshwar Hamleys ESPLANADEONE-OD-BBR Chandigarh -

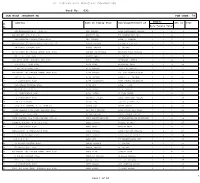

Supplementary List of BPL Households 2013-14 095 ULB

Supplementary List of BPL Households Ward No: 095 2013-14 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID No Male Female Total 1 1/38 ,ARABINDA NAGAR ,JADAVPUR ,700032 ADITYA KUMAR PANDEY SURAJ PRASAD PANDEY 2 3 5 375 2 18A ,BIKRAMGARH COLONY ,BIKRAMGARH COLONY ,700032 ALO BRAHMA UPENDRA BRAHMA 0 1 1 376 3 3/120A ,AZADAGRH COLONY ,.......... ,700040 AMAR DAS LATE MANGAL DAS 3 1 4 377 4 121 ,REGEN PARK ,N S C BOSE ROAD ,700040 AMIT CHADRA DUTTA LATE AKUIT CHANDRA DUTTA 1 1 2 527 5 2/73A ,REGENT COLONY ,REGENT PARK ,700040 ANITA RANI MONDAL KANU MOHAN MONDAL 0 1 1 378 6 33E ,PRINCE GOLAM HOSSAINSHAH ROAD ,BIKRAM GALI ,700032 ANJALI CHOWDHURY LATE TAPAS CHOWDHURY 3 1 4 379 7 1/42 ,AZAD GARH COLONY ,MINA PARA ROAD ,700040 ANJALI DAS BIMAL DAS 1 2 3 380 8 81/13A ,REGENT COLONY ,REGENT COLONY ,700040 ANJALI GUHA LATE BIMAL KR. GUHA 0 1 1 381 9 44 ,NEW BIKRAMGARH ,NEW BIKRAMGARH ,700032 ANU SARKAR SIBESWAR SARKAR 1 1 2 382 10 22/B ,TIALGARH COLONY ROAD ,TILAK GARH COLONY ,700040 ANUPAMA DUTTA SITANGSHU DUTTA 2 2 4 383 11 22C ,TILAK NAGAR ,TOLLY GUNGE ,700040 ANURADHA DAS LATE HARI NARAYAN DAS 0 2 2 384 12 9/11 ,NEW BIKRAMGARH ,JADAVPUR ,700032 APARNA SAHA LATE PROJAL KUMAR SAHA 0 2 2 385 13 2/57 ,ARANBIBDANAGAR ,ARANBIBDANAGAR ,700040 ARATI SANYAL ANIL SANYAL 1 3 4 386 14 4/28 ,AZADGARH COLONY ,AZADGARH COLONY ,700040 ARATI DEBNATH LATE GOUR DEBNATH 5 7 10+ 387 15 2/A ,SAMAJGARH ,SANAJGARH ,700040 ARCHANA MONDAL JATIN MONDAL 2 2 4 388 16 8/83 ,BIJOYGARH COLONY ,JADAVPUR ,700032 ARUN BANIK LATE