An Excursion to Asmara (Via Djibouti, of Course)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amembassy Nairobi T1 1 Parana

AMEMBASSY NAIROBI T1 1 PARANA Wooll'UT ABA 4993/1 111105 •LNY CCCCC ZZH R 271006Z APR 76 FM AMEt,IBASSY ADDIS ABABA TO RUEHC/SECSTATE. WASH DC 9152 INFO RUTABA/AMCONSUL ASMARA 7298 RLEHEG/AMEMBASSY CAIRO 692 RUC;MM/AMEMBASSY KHARTOUM 2585 RUDTC/AMEMBASSY LONDON 937 Fc UOD I/AMEMBASSY MOGAD IS CIO 4304 R1EHMO/AMEMBASSY MOSCOW 336 R LIESAI/AMEMBASSY NAIROBI 3043 RUFNP S/AMENBASSY PARIS 2979 R UMJPG/USLO PE KING 071 ADDIS AEABA 4993 E.O. 11652: GDS TAGS: PFOR PINT • SUBJECT: THE SETTING FOR ETHIOPIA'S LEFTWARD LURCH 1. EMBASSY WILL BE ATTEMPTING IN OTHER MESSAGES TO MAKE SENSE OF DEVELOPMENTS IN ETHIOPIA IN PAST FEW WEEKS, AND THEIR IMPLICA - TIONS FOR US POLICY. THIS MESSAGE TRIES TO OUTLINE, IN OVER SIMPLIFIED TERMS, SOME OF THE MAJOR BACKGROUND ELEMENTS AGAINST—' WHICH FUTURE REPORTING CAN BE VIEWED. 2. THE REVOLUTION THAT BEGAN OVER TWO YEARS AGO HAS PRODUCED A NUMBER OF .DESIRABLE CHANGES- -- ` LAZ REFOR::; BETTER USE OF TRAINED MANPOWER; REDISTRIBUTION OF INCOME IN FAVOR OF LOW INCOME GROUPS; ATTEMPTS TO EXTEND GOVT SERVICES MORE WIDELY, ESPECIALLY TO THE RURAL AREAS; THE BEGINNINGS OF LOCAL SELF—GOVERNMENT IN THE FORM OF PEASANT ASSOCIATIONS AND URBAN ORGANIZATIONS, ETC. HIGH COFFEE PRICES, A GOOD GRAIN HARVEST, AND COMPETENT MANAGEMENT OF NATIONALIZED BUSINESS ENTERPRISES HAVE. MINIMIZED ECONOMIC STRESSES. ALTHOUGH R IS I tsIG PRIGS HAVE REDUCED T F. CO NOM IC EZNEFITS THAT 'POOR L3: PEOPLE EIGHT OTHER S • HAVE EXPER IE NCED , THIS GOVT HAS NEVERTHELESS IMPROVED 'EH:Li -MATER IAL itZLFARE, IN SOME CASES TO A SUBSTANTIAL DEGREE. -

Building Peace in Eastern Africa

International Peace Academy Makerere University, Uganda Africa Peace Forum, Kenya Building Peace in Eastern Africa Rapporteurs: Dr. Dorina A. Bekoe and Dr. Paul Omach DECEMBER 2002 ■ ENTEBBE, UGANDA Acknowledgements International Peace Academy’s Africa Program gratefully acknowledges the support of the governments of Denmark, Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID). About IPA’s Africa Program The seminar on building peace in Eastern Africa, organized jointly by the International Peace Academy (IPA), the Faculty of Social Sciences at Makerere University (Uganda), and the Africa Peace Forum (Kenya), took place in Entebbe, Uganda, from 16 to 18 December 2002. The meeting involved about fifty diplomats, soldiers, academics, and civil society actors, drawn largely from Eastern Africa, and was the third in a series of three policy seminars to address ways in which Africa’s sub-regional organizations can increase their capacity to manage local conflicts. The seminar was also part of the IPA Africa Program’s current three-year project (2000-2003) on developing regional and sub-regional security mechanisms in Africa. This work followed seven years of collaboration between IPA and the Organization of African Unity (OAU) between 1992 and 1998. In a bid to enhance African efforts at developing regional and sub-regional security mechanisms, IPA is working with partner institutions in Africa to: • Assess major challenges faced by sub-regional organizations in Africa in their efforts -

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa: A Threat Assessment Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org OrgAnIzed CrIme And Instability In CenTrAl AFrica A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2011 – 750 October 2011 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa A Threat Assessment Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Acknowledgements This study was undertaken by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA). Researchers Ted Leggett (lead researcher, STAS) Jenna Dawson (STAS) Alexander Yearsley (consultant) Graphic design, mapping support and desktop publishing Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) Thibault le Pichon (Chief, STAS) The preparation of this report would not have been possible without the data and information reported by governments to UNODC and other international organizations. UNODC is particularly thankful to govern- ment and law enforcement officials met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda while undertaking research. Special thanks go to all the UNODC staff members - at headquarters and field offices - who reviewed various sections of this report. The research team also gratefully acknowledges the information, advice and comments provided by a range of officials and experts, including those from the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO (including the UN Police and JMAC), IPIS, Small Arms Survey, Partnership Africa Canada, the Polé Institute, ITRI and many others. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

Bibliographic Guide to Further Reading

BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO FURTHER READING The historical, memoir, travel, and technical literature on Ethiopia is immense and continually growing. A complete bibliography would require a very thick volume. Included below are most of the major books cited in the text. Journal articles, pamphlets and monographs are not included. Many worthwhile books from my own collection not specifically referenced in the footnotes have been added. Books in languages other than English, German, French, Italian and Portu guese are not listed. Among the most valuable sources for research on Ethiopia are the proceedings of the triennial International Ethiopian Studies Conferences (IESC), the most recent of which were held in East Lansing, Michigan in September 1994 and in Kyoto,Japan in Decem ber 1997. The former produced 2,372 pages of papers published as New Trends in Ethiopian Studies (2 vols. Red Sea Press, No. 1994). The latter resulted in 2,345 pp. of papers published as Ethiopia in Broader Perspective (Shokado, Kyoto, 1997, 3vols). The 14th IESC is scheduled to take place in Addis Ababa in November 2000. Many other volumes of conference proceedings have been published in Ethiopia and elsewhere during the past three decades. With only a few except ions, these have not been listed below. HISTORY AND CULTURE, GENERAL Berhanou Abebe, Historie de lithiopie d'Axoum ala revolution, Maison neuve et Larose, Paris, 1998. E. A. Wallis Budge, History ofEthiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, Methuen, London, 192R David Buxton, The Abyssinians, Thames & Hudson, London, 1970. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski, Ethiopia sAccess to the Sea, EJ. Brill, Leiden, 1985. Jean Doresse, Ethiopia, Elee, London, 1959. -

The Case of African Cities

Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Currie, Paul, et al. "Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities." Journal of Environmental Protection 6, 9 (September 2015): 1066-1083 © 2015 Author(s) As Published 10.4236/JEP.2015.69094 Publisher Scientific Research Publishing, Inc, Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/124946 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Journal of Environmental Protection, 2015, 6, 1066-1083 Published Online September 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2015.69094 Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities Paul Currie1*, Ethan Lay-Sleeper2, John E. Fernández2, Jenny Kim2, Josephine Kaviti Musango3 1School of Public Leadership, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa 2Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA 3School of Public Leadership, and the Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies (CRSES), Stellenbosch, South Africa Email: *[email protected] Received 29 July 2015; accepted 20 September 2015; published 23 September 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Data sourcing challenges in African nations have led many African urban infrastructure develop- ments to be implemented with minimal scientific backing to support their success. -

International Geography Exam Part 2

2018 International Geography Bee 7. Which of these Washington cities is driest due to rain International Geography Exam - Part 2 shadow? A. Seattle B. Tacoma Instructions – This portion of the IGB Exam consists of C. Bellingham 100 questions. You will receive two points for a correct D. Spokane answer. You will lose one point for an incorrect answer. Blank responses lose no points. Please fill in the bubbles 8. The Karakum Desert in Central Asia is bordered by completely on the answer sheet. You may write on the what two mountain ranges? examination, but all responses must be bubbled on the A. Ural and Atlas answer sheet. Diacritic marks such as accents have been B. Caucasus and Hindu Kush omitted from place names and other proper nouns. You C. Hindu Kush and Yin have one hour to complete this set of multiple choice D. Caucasus and Ural questions. 9. All of these contain parts of the Kalahari Desert 1. Which of these best defines the term intergovernmental EXCEPT which of the following? organization? A. South Africa A. a multinational corporation B. Kenya B. a treaty with multiple nations as signatories C. Namibia C. an organization composed of sovereign states D. Botswana established by a charter or treaty D. an international aid agency 10. All of these border the Red Sea’s western shore EXCEPT which of the following? 2. Which of the following is an example of an A. Saudi Arabia intergovernmental organization? B. Egypt A. the United Nations C. Djibouti B. the International Red Cross D. Sudan C. the Quartet D. -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

African Adventure? Assessing the European Union’S Military Intervention in Chad and the Central African Republic

Massachusetts Institute of Technology African Adventure? Assessing the European Union’s Military Intervention in Chad and the Central African Republic by Bjoern H. Seibert MIT CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES MIT Security Studies Program 292 Main Street, 6th Floor Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 phone +1.617.258.7608 MIT Security Studies Program Working Paper web web.mit.edu/ssp November 2007 SSP Working Paper: African Adventure MIT Security Studies Program Working Paper November 2007 African Adventure? Assessing the European Union’s Military Intervention in Chad and the Central African Republic Bjoern H. Seibert SSP Working Paper: African Adventure Bjoern H. Seibert is a MALD candidate at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a mem- ber of the International Security Studies Program (ISSP) at The Fletcher School. Previously, he worked for the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research (AEI) and the German Federal Armed Forces. The Security Studies Program at MIT is a graduate-level research and educational program based at the Center for International Studies at MIT. The senior research and teaching staff includes social scientists and policy analysts. A special feature of the program is the integration of technical and po- litical analysis of national and international security problems. Security Studies is a recognized field of study in the MIT Political Science Department. Courses emphasize grand strategy, the causes and prevention of conflict, military operations and technology, and defense policy. 2 SSP Working -

COUNTRY UPDATE: ERITREA August 2019

UNITED STATES COMMISSION on INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM COUNTRY UPDATE: ERITREA August 2019 Tony Perkins By Ferdaouis Bagga, Policy Analyst Chair Gayle Manchin Background Vice Chair On July 9, 2018, Eritrea crossed a new milestone in its history—the signing of the Nadine Maenza “Joint Declaration of Peace and Friendship” agreement with Ethiopia. In September, Vice Chair the two countries reaffirmed their commitments in Saudi Arabia. The signing of the agreement marked the beginning of renewed engagement within East Africa and the Commissioners international community after decades of being heavily isolated and militarized, in a Kristina Arriaga constant state of conflict. Swift changes brought the opening of borders and restoration Commissioner of diplomatic relations, economic exchange, transportation, and communications that had been blocked for nearly two decades. The political deals brought fresh hope Gary Bauer and joy to many Eritreans who were able to reconnect with loved ones outside the Commissioner country. Yet almost a year later, practices of isolation and militarized control linger. Anurima Bhargava Between December 2018 and April 2019 Eritrea again closed border crossings. At the Commissioner same time, the government has not announced any plans to demobilize and end the indefinite national service predicated on the state of war. Moreover, it continues to Tenzin Dorjee violate religious freedom. Commissioner Andy Khawaja Ongoing Religious Freedom Limitations Commissioner The ruling regime in Eritrea, in power since the country’s independence in 1993, Johnnie Moore directly limits freedom of religion or belief, such as through its exclusive registration Commissioner requirements and the recognition of only four faith communities, the marginalization and persecution of non-registered religious groups, and heavy interference in the affairs of registered religious groups. -

Towards a Union Government for Africa

TOWARDS A UNION GOVERNMENT FOR AFRICA CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES EDITED BY TIMOTHY MURITHI ISS MONOGRAPH SERIES • No 140, JANUARY 2008 CONTENTS PreFACE v Kenneth Mpyisi, Institute for Security Studies, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ACKnoWLEDgemenTS vii ABOUT The AUThors viii ABBreViaTions anD ACronYms x ChapTer 1 1 Introduction: Contextualising the debate on a Union Government for Africa Dr Tim Murithi, Institute for Security Studies, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia PART ONE 11 A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR A UNION GOVERNMENT FOR AFRICA ChapTer 2 13 Portrayal of a possible path to a single government for Africa Dr Admore Kambudzi, African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ChapTer 3 29 The challenges of accelerating economic and political integration in the formation of a Union Government The late Professor Kinfe Abraham, Ethiopian International Institute for Peace and Development, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia PART TWO 43 ENGAGING WITH THE ACCRA DECLARATION ChapTer 4 45 Reflections on the 2007 Accra Grand Debate on a Union Government for Africa Delphine Lecoutre, Independent Consultant, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ii Towards a Union Government for Africa: Challenges and Opportunities ChapTer 5 61 The relationship between states and an African Union Government Professor Ismail Fall, University of Dakar, Senegal ChapTer 6 69 Rationalising regional economic communities and implementing the treaty establishing the African Economic Community: The role of parliaments Marilyn Aniwa, Parliamentary Centre, Accra, Ghana ChapTer 7 79 Identifying the domains of competence -

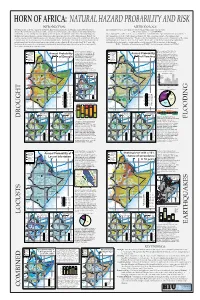

Flooding Locusts Drought Earthquakes Combined

HORN OF AFRICA: NATURAL HAZARD PROBABILITY AND RISK INTRODUCTION: METHODOLOGY: The Horn of Africa (HOA), composed of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia, suffers frequent natural The probability of one or more hazard events occurring within a grid cell is given by disasters that commonly result in losses of life, destruction of infrastructure, and reduction of agricultural production. P(1 or more events) = 1 - exp(-E[N(HI)]), Formulating effective contingencies to respond to such emergencies is constrained by a limited understanding of the where E[N(HI)] = λ(HI)*T. E is the expected number of events within time T given historical rate of occurrence λ. likelihood of a natural hazard occurring within a particular region and risks associated with that hazard. Robust early The summation is over all events within a given grid cell. This calculation assumes a Poissonian, or time- warning systems exist for national response and "hot spot" maps of risk have been produced at a global level; this level of independent, distribution of probability. This means that the probability of a future event is independent of the timing resolution, however, is often not sufficient for sub-national resource distribution. This study presents the probabilities of and magnitude of the most recent events in the region. The measure of risk R(HI) is obtained by combining the natural hazards and the risk to populations or agricultural systems within the HOA, calculated on 1° by 1° grid cells. probability P(HI) of a hazard occurring with the societal exposure X(HI), or exposure, to that hazard: Such an analysis can provide a regional understanding of the probability of natural hazards as well as a more specific R(HI) = Probability of hazard occurring [P(HI)] * Societal exposure to that hazard [X(HI)].