Clackmannan Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members' Centre and Friends' Group Events

MEMBERS’ CENTRE AND FRIENDS’ GROUP EVENTS AUTUMN/WINTER 2019 Joining a centre or group is a great way to get more out of your membership and learn more about the work of the Trust. All groups also raise vital funds for Trust places and projects across the country. Please note that most groups charge a small annual membership subscription, separate to your Trust membership. The groups host a range of lectures, outings, social events and tours for their members throughout the year. For more information please contact each group directly. ABERDEEN AND DISTRICT MEMBERS’ Thursday 13 February, 2.00pm: Talk by Dr Thursday 3 October, 2.15pm: Annual CENTRE (SC000109) Fiona-Jane Brown “Forgotten Fittie” at the general meeting, followed by a talk from Ben Aberdeen Maritime Museum, Shiprow. Judith Falconer, Programme Secretary Reiss of the Morton Photography Project, which has supported the Trust in curating Tel: 01224 938150 Tuesday 17 March, 7.30pm: Annual general and conserving its photographic collection. Email: [email protected] meeting followed by a talk by Gordon Guide Hall, Myre Car Park, Forfar. Murdoch “Join the National Trust….. and see Booking is essential for events marked * the world” at the Aberdeenshire Cricket October date TBC: Visit to Drum Castle to There is a charge for guests attending talks. Club, Morningside Road. see the “A Considered Place” exhibition. For further information, please contact the Tuesday 17 September, 7.30pm: Talk by * Day excursion in early May TBC Membership Secretary. Finlay McKichan “Lord Seaforth: Highland landowner, Caribbean governor and slave * Annual holiday in early June TBC Saturday 2 November, 10–12 noon: Coffee owner” at the Aberdeenshire Cricket Club, morning at the Old Parish Church Hall, Morningside Road. -

Fnh Journal Vol 28

the Forth Naturalist and Historian Volume 28 2005 Naturalist Papers 5 Dunblane Weather 2004 – Neil Bielby 13 Surveying the Large Heath Butterfly with Volunteers in Stirlingshire – David Pickett and Julie Stoneman 21 Clackmannanshire’s Ponds – a Hidden Treasure – Craig Macadam 25 Carron Valley Reservoir: Analysis of a Brown Trout Fishery – Drew Jamieson 39 Forth Area Bird Report 2004 – Andre Thiel and Mike Bell Historical Papers 79 Alloa Inch: The Mud Bank that became an Inhabited Island – Roy Sexton and Edward Stewart 105 Water-Borne Transport on the Upper Forth and its Tributaries – John Harrison 111 Wallace’s Stone, Sheriffmuir – Lorna Main 113 The Great Water-Wheel of Blair Drummond (1787-1839) – Ken MacKay 119 Accumulated Index Vols 1-28 20 Author Addresses 12 Book Reviews Naturalist:– Birds, Journal of the RSPB ; The Islands of Loch Lomond; Footprints from the Past – Friends of Loch Lomond; The Birdwatcher’s Yearbook and Diary 2006; Best Birdwatching Sites in the Scottish Highlands – Hamlett; The BTO/CJ Garden BirdWatch Book – Toms; Bird Table, The Magazine of the Garden BirthWatch; Clackmannanshire Outdoor Access Strategy; Biodiversity and Opencast Coal Mining; Rum, a landscape without Figures – Love 102 Book Reviews Historical–: The Battle of Sheriffmuir – Inglis 110 :– Raploch Lives – Lindsay, McKrell and McPartlin; Christian Maclagan, Stirling’s Formidable Lady Antiquary – Elsdon 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 28 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, University of Stirling – charity SCO 13270 and member of the Scottish Publishers Association. November, 2005. ISSN 0309-7560 EDITORIAL BOARD Stirling University – M. Thomas (Chairman); Roy Sexton – Biological Sciences; H. Kilpatrick – Environmental Sciences; Christina Sommerville – Natural Sciences Faculty; K. -

Examining the Test: an Evaluation of the Police Standard Entrance Test. INSTITUTION Scottish Council for Research in Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 249 TM 027 914 AUTHOR Wilson, Valerie; Glissov, Peter; Somekh, Bridget TITLE Examining the Test: An Evaluation of the Police Standard Entrance Test. INSTITUTION Scottish Council for Research in Education. SPONS AGENCY Scottish Office Education and Industry Dept., Edinburgh. ISBN ISBN-0-7480-5554-1 ISSN ISSN-0950-2254 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 104p. AVAILABLE FROM HMSO Bookshop, 71 Lothian Road, Edinburgh, EH3 9AZ; Scotland, United Kingdom (5 British pounds). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Employment Qualifications; Foreign Countries; Job Skills; Minority Groups; *Occupational Tests; *Police; Test Bias; *Test Interpretation; Test Use; *Testing Problems IDENTIFIERS *Scotland ABSTRACT In June 1995, the Scottish Council for Research in Education began a 5-month study of the Standard Entrance Examination (SET) to the police in Scotland. The first phase was an analysis of existing recruitment and selection statistics from the eight Scottish police forces. Phase Two was a study of two police forces using a case study methodology: Identified issues were then circulated using the Delphi approach to all eight forces. There was a consensus that both society and the police are changing, and that disparate functional maps of a police officer's job have been developed. It was generally recognized that recruitment and selection are important, but time-consuming, aspects of police activity. Wide variations were found in practices across the eight forces, including the use of differential pass marks for the SET. Independent assessors have identified anomalies in the test indicating that it is both ambiguous and outdated in part, with differences in the readability of different versions that compromises comparability. -

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire

Supporting Rural Communities in West Dunbartonshire, Stirling and Clackmannanshire A Rural Development Strategy for the Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area 2015-2020 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Area covered by FVL 8 3. Summary of the economies of the FVL area 31 4. Strategic context for the FVL LDS 34 5. Strategic Review of 2007-2013 42 6. SWOT 44 7. Link to SOAs and CPPs 49 8. Strategic Objectives 53 9. Co-operation 60 10. Community & Stakeholder Engagement 65 11. Coherence with other sources of funding 70 Appendix 1: List of datazones Appendix 2: Community owned and managed assets Appendix 3: Relevant Strategies and Research Appendix 4: List of Community Action Plans Appendix 5: Forecasting strategic projects of the communities in Loch Lomond & the Trosachs National Park Appendix 6: Key findings from mid-term review of FVL LEADER (2007-2013) Programme Appendix 7: LLTNPA Strategic Themes/Priorities Refer also to ‘Celebrating 100 Projects’ FVL LEADER 2007-2013 Brochure . 2 1. Introduction The Forth Valley and Lomond LEADER area encompasses the rural areas of Stirling, Clackmannanshire and West Dunbartonshire. The area crosses three local authority areas, two Scottish Enterprise regions, two Forestry Commission areas, two Rural Payments and Inspections Divisions, one National Park and one VisitScotland Region. An area criss-crossed with administrative boundaries, the geography crosses these boundaries, with the area stretching from the spectacular Highland mountain scenery around Crianlarich and Tyndrum, across the Highland boundary fault line, with its forests and lochs, down to the more rolling hills of the Ochils, Campsies and the Kilpatrick Hills until it meets the fringes of the urbanised central belt of Clydebank, Stirling and Alloa. -

Ochils Festival

Ochils 9th–2 Festival 3 rd Jun e a t ve 2012 nue s a cro ss t he H illfoots Landscape | Heritage | People About the festival The Ochils Festival How to book: Booking The Ochils Landscape l All events are FREE! Partnership is a partnership project of 20 local organisations l Booking is required for some events. Please contact aiming to deliver 22 built, natural Kirsty McAlister, providing the names and contact and cultural heritage projects by details (postal and email addresses as well as phone the end of 2014. numbers) of everyone you wish to book onto an event. The overall aims of the projects are to improve access l Phone: 01259 452675 to the Ochil Hills and River Devon, restore some of the built heritage in the area, and provide on-site and l on-line interpretation about the area's cultural, social Email: [email protected] and industrial past. l Post: please return the tear-off form on the back The Ochils Festival is here to encourage a greater page of this booklet to: understanding and appreciation of the Ochils and Kirsty McAlister, Ochils Landscape Partnership, Hillfoots among locals and visitors alike - there is Kilncraigs, Greenside Street, Alloa, FK10 1EB something for everyone! There are walks, talks, workshops and fun family activities designed to help l If you need to cancel your booking at any point, people discover more about the area and celebrate the please contact Kirsty McAlister on 07970 290 868 significant landscape heritage of the Ochils. so that your place can be re-allocated. -

Doors Open Days 2017 in Clackmannanshire

Doors Open Days 2017 in Clackmannanshire 23rd & 24th September Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology Doors Open Days 2017 In Clackmannanshire Doors Open Days is celebrated in September throughout Scotland as part of the Council of Europe European Heritage Days. People can visit free of charge places of cultural and historic interest which are not normally open to the public. The event aims to encourage everyone to appreciate and help to preserve their built heritage. Doors Open Days is promoted nationally by The Scottish Civic Trust with part sponsorship from Historic Environment Scotland. In this Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology we will be celebrating buildings and archaeological and industrial landmarks. Special events in Clackmannan will include Heritage Trail Walks and performances of Tales of Clackmannan by the Walking Theatre Company. There will be guided tours of Clackmannan and Sauchie Towers and a display of memorabilia relating to Bonnie Prince Charlie in Alloa Tower. New heritage walks exploring the former Alloa House estate and Alloa Wagon Way, generated by the work of the Inner Forth Landscape Initiative project A Tale of Two Estates, will also take place. St Mungo’s Parish Church in Alloa and Clackmannan Doors Open Days 2017 In Clackmannanshire Parish Church are celebrating their Bicentenaries, while Sauchie and Coalsnaughton Parish Church is commemorating its 175th anniversary. Many other properties and sites are also featured, including Tullibole Castle, which is taking part in this programme for the first time. Please note that in some buildings only the ground floor is accessible to people with mobility difficulties. Please refer to the key next to each entry. -

Discovering Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites

DISCOVERING BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE & THE JACOBITES NATIONAL MUSEUM PALACE OF EDINBURGH STIRLING KILLIECRANKIE ALLOA TOWER LINLITHGOW OF SCOTLAND HOLYROODHOUSE CASTLE CASTLE PALACE DOUNE CASTLE The National Trust for Scotland HUNTINGTOWER Historic Scotland CASTLE National Museum of Scotland Palace of Holyroodhouse CULLODEN BATTLEFIELD Thurso BRODIE CASTLE Lewis FORT GEORGE Ullapool Harris Poolewe North Fraserburgh Uist Cromarty Brodie Castle URQUHART A98 Benbecula Fort George A98 CASTLE A947 Nairn A96 South Uist Fyvie Castle Skye Kyle of Inverness Culloden Huntly Lochalsh Battlefield Kildrummy A97 Leith Hall Barra Urquhart Castle Canna Castle DRUM CASTLE A887 A9 Castle Fraser A944 A87 Kingussie Corgarff Aberdeen Rum Glenfinnan Castle Craigievar Drum Monument A82 Castle A830 A86 Eigg Castle Fort William A93 A90 A92 A9 House Killiecrankie of Dun FYVIE CASTLE A861 Glencoe Pitlochry A924 Montrose Tobermory A933 A82 Glamis Dunkeld Craignure Dunstaffnage Castle A827 A822 Dundee Staffa Burg A92 Mull A85 Crianlarich Perth Huntingtower CASTLE FRASER Iona Oban A85 Castle A9 St Andrews M90 Doune Castle Alloa Tower Stirling Castle Stirling Helensburgh A811 Edinburgh Tenement M80 CRAIGIEVAR House Glasgow CASTLE Linlithgow A8 Dumbarton Edinburgh Palace A1 Glasgow Castle M8 A74 A7 Berwick M77 EdinburghA68 M74 Pollok House Ardrossan A737 A736 Castle M74 A72 A83 National Palace of LEITH HALL A726 Holmwood A749 A841 Museum of Holyroodhouse Ayr Scotland Greenbank Garden A725 A68 Moffat DUMBARTON DUNSTAFFNAGE GLENFINNAN GLENCOE HOUSE OF DUN CORGARFF KILDRUMMY CASTLE CASTLE MONUMENT Dumfries CASTLE CASTLE Stranraer Kirkcudbright The Palace of Holyroodhouse image: Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016. Photographer: Sandy Young DISCOVERING BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE & THE JACOBITES The story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) and the Jacobites is embedded in Scotland’s rich and turbulent history, resonating across the centuries. -

Clackmannanshire View, Issue 10, Summer 2011

Issue 10 Summer 2011 Wedding belles grace refurbished town hall ...more on page 5 Work set to begin on new Council houses Council houses are set to be Work will begin at the end of towards addressing the serious A central element of the project homes for older people will built in Clackmannanshire July this year and is expected to imbalance we face between is the continued regeneration be provided at the current for the first time in over 30 last 17 months. genuine housing need and the of the Newmills/Orchard area Dalmore Centre, Alva. There availability of Council houses. of Tullibody begun by Ochil will be four one-bedroom and years. Council leader Sam Ovens said: They will also be affordable, View Housing Association. The four two-bedroom houses. “Clackmannanshire Council is The £2.3 million project will energy efficient and accessible. Council will construct 16 new The Dalmore Centre, which committed to providing quality, see 24 new houses being The last houses built for rent 2-bedroom houses for rent on is a former infant school, was affordable housing for the built in Tullibody and Alva. by the Council were in Sauchie the site currently occupied by listed last year and ongoing people of Clackmannanshire. This funding includes a in the mid 70s, so this decision lock ups at 80-98 Newmills. feasibility work for the site is These new homes are contribution of £600,000 from marks a new era for social subject to detailed discussions desperately needed and And eight much needed the Scottish Government. -

Asva Visitor Trend Report - September 2009/2010

ASVA VISITOR TREND REPORT - SEPTEMBER 2009/2010 OVERVIEW Visitor numbers for September 2009/2010 were received from 218 sites. 9 sites requested confidentiality, and although their numbers have been included in the calculations, they do not appear in the tables below. There are 14 sites for which there is no directly comparable data for 2009. The 2010 figures do appear in the table below for information but were not included in the calculations. Thus, directly comparable data has been used from 204 sites. From the usable data from 204 sites, the total number of visits recorded in September 2010 was 1,551,800 this compares with 1,513,324 in 2009 and indicates an increase of 2.5% for the month. Weatherwise, September was a changeable month with rain and strong winds, with average rainfall up to 150% higher than average Some areas experienced localised flooding and there was some disruption to ferry and rail services. The last weekend of the month saw clear skies in a northerly wind which brought local air frosts to some areas and a few places saw their lowest temperatures in September in 20 to30 years. http://news.bbc.co.uk/weather/hi/uk_reviews/default.stm September 2009 September 2010 % change SE AREA (156) 1,319,250 1,356,219 2.8% HIE AREA (48) 194,074 195,581 0.8% SCOTLAND TOTAL (204) 1,513,324 1,551,800 2.5% Table 1 – Scotland September 2009/2010 SE AREA In September 2010 there were 1,356,219 visits recorded, compared to 1,319,250 during the same period in 2009, an increase of 2.8%. -

A Walk in the Country

ISSN 0262-2211 CLACKMANNANSHIRE FIELD STUDIES SOCIETY Clackmannanshire The CFSS was formed in October 1970 after attempting to revive the Alloa Society of Natural Science and Archaeology established in 1865. The society‟s aims are “to promote interest in the environment and heritage of the local area” and it has some 150 members. Field In winter there are fortnightly lectures or member‟s nights, from September to April, beginning with a coffee morning and concluding with the AGM. In Studies summer, from April to September, there are four Saturday outings, a weekend event and Wednesday Evening Walks fortnightly from April to August. CFSS has run and participated in various events on David Allan and at Alloa Society Tower, is associated with the Forth Naturalist and Historian in publishing, and with the annual Man and the Landscape symposium – Conserving Biodiversity th th and Heritage and Loch Lomond and the Trossachs are the 26 and 27 . Research projects have included- Linn Mill, Mining, and Alloa Harbour; these Newsletter have been published as booklets Linn Mill, Mines and Minerals of the Ochils, and Alloa Port, Ships and Shipbuilding. A recent project is Old Alloa Kirkyard, ____________________________69 Archaeological Survey 1996 – 2000 further work is in progress. Other publications include David Allan, The Ochil Hills – landscape, wildlife, heritage walks; Alloa Tower and the Erskines of Mar; and the twice yearly Newsletter with 5 yearly contents / indices. Membership is open to anyone with an interest in, or desire to support the aims of the society in this field of Local Studies. Vol. 31 The society has a study / council room in Marshill House, Alloa. -

2013 ASVA Visitor Trend Report Dashboard Summary

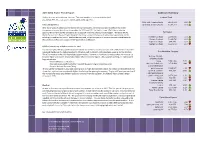

2013 ASVA Visitor Trend Report Dashboard Summary Usable data was received from 249 sites. The total number of visits recorded in 2013 Scotland Total was 32,542,556; this compares to 32,393,441 in 2012 (up 0.5%). 2013 (incl. Country Parks) 32,542,556 0.5% p Acknowledgements 2013 (excl. Country Parks) 22,971,222 0.1% p After many years of publishing monthly benchmarking reports, ASVA has been able to achieve the direct comparison of annual data from its members for 2013 and 2012 for the first time. We’d like to take the opportunity to thank Scottish Enterprise for its support which has allowed this to happen. We’d also like to Per Region thank the team at LJ Research who designed the online survey (complete with embedded algorithms) and for collating this data on our behalf. And last but not least, a big thank you to all our members who contributed to Northern Scotland 2,669,893 7.7% p this survey as without your support there would be no publication. Eastern Scotland 12,403,741 0.2% p Southern Scotland 864,768 6.1% p Western Scotland 16,604,154 -0.7% q ASVA's Commentary and Observation for 2013 For the third year, the National Museum of Scotland was the most visited attraction with 1,768,090 visits recorded. Edinburgh Castle was the highest paid entry attraction with 1,420,027 visits. (See table , page 4, for top 20 sites.) Per Attraction Category The 0.5% increase in the table above does appear modest. -

Castle Campbell

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC016 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13611) GDL Inventory Landscape (00089); Taken into State care: 1950 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CASTLE CAMPBELL We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CASTLE CAMPBELL SYNOPSIS Castle Campbell stands in lofty isolation on a narrow rocky spur at the head of Dollar Glen, 1 mile north of Dollar. The spur is cut off from the east, west and south by the ravines of the Burns of Care and Sorrow, whilst the Ochil Hills overlook it from the north. The castle has splendid views southward over the Forth valley. The site may be of some antiquity but the present castle complex most probably dates from the early 15th century. Initially called Castle Gloom, it became the Lowland residence of the Campbell earls of Argyll around 1465 – whence the name Castle Campbell. It remained with that powerful noble family until the 9th earl relocated to Argyll’s Lodging, Stirling, in the mid-17th century. Thereafter, the castle fell into ruin. The Campbell earls substantially rebuilt the lofty tower house that dominates the complex, then added a once-splendid but now substantially ruined hall range across the courtyard c.