American University Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playing the Sacred Harp: Mennonite Literature As Confession (The

Playing the Sacred Harp: Mennonite Literature as Confession Ann Hostetler Borrowed hymnal in hand, I walk into the one-room white clapboard church that vibrates with loud singing, past dozens of onlookers and would-be participants hovering at the doors like honeybees. My daughter and her partner and their two-week-old baby, and a friend of theirs, follow me as we squeeze into the standing room at the back of the sanctuary next to a row of Old Order Mennonites. Sacred Harp music is sung a cappella and needs a body of singers to come to life in a corporeal act of worship, creating what an alternative healer might call a highly-charged energy fi eld. One of my more worldly friends who is a Sacred Harp devotee describes it as a form of yoga, centered on breathing. Surrounded by the fi erce organ of many voices, I have visions of seraphim and cherubim vibrating with the music of the spheres. Someone less inclined to ecstatic merger might recall Huck Finn’s opinions of Aunt Polly’s heaven – that if the saints were singing for eternity, he would rather spend his time elsewhere. We have chosen to stay for the day. Sacred Harp singers travel. They come from many places, denominations, even faiths to gather at conventions or at singings in many parts of the country. They hold local sings and long-distance sings. The only rule is respect for the music and each other. The content of the songs, sung fi rst by rural Southerners and then Midwestern pioneers during the nineteenth-century singing school movement, is profoundly religious, focusing on death and salvation. -

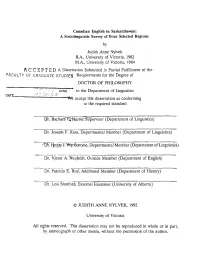

A C C E P T E

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

A Finding Aid to the Emigration And

A Finding Aid to the Emigration and Immigration Pamphlets Shortt JV 7225 .E53 prepared by Glen Makahonu k Shortt Emigration and Immi gration Pamphlets JV 7225 .E53 This collection contains a wide variety of materials on the emigration and immigration issue in Canada, especially during the period of the early 20th century. Two significant groupings of material are: (1) The East Indians in Canada, which are numbered 24 through 50; and (2) The Fellowship of the Maple Leaf, which are numbered 66 through 76. 1. Atlantica and Iceland Review. The Icelandic Settlement in Cdnada. 1875-1975. 2. Discours prononce le 25 Juin 1883, par M. Le cur6 Labelle sur La Mission de la Race Canadienne-Francaise en Canada. Montreal, 1883. 3. Immigration to the Canadian Prairies 1870-1914. Ottawa: Information Canada, 19n. 4. "The Problem of Race", The Democratic Way. Vol. 1, No. 6. March 1944. Ottawa: Progressive Printers, 1944. 5. Openings for Capital. Western Canada Offers Most Profitable Field for Investment of Large or Small Sums. Winnipeg: Industria1 Bureau. n.d. 6. A.S. Whiteley, "The Peopling of the Prairie Provinces of Canada" The American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 38, No. 2. Sept. 1932. 7. Notes on the Canadian Family Tree. Ottawa: Dept. of Citizenship and Immigration. 1960. 8. Lawrence and LaVerna Kl ippenstein , Mennonites in Manitoba Thei r Background and Early Settlement. Winnipeg, 1976. 9. M.P. Riley and J.R. Stewart, "The Hutterites: South Dakota's Communal Farmers", Bulletin 530. Feb. 1966. 10. H.P. Musson, "A Tenderfoot in Canada" The Wide World Magazine Feb. 1927. 11. -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

A Thesis for the Degree of University of Regina Regina, Saskatchewan

Hitched to the Plow: The Place of Western Pioneer Women in Innisian Staple Theory A Thesis Subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina by Sandxa Lynn Rollings-Magnusson Regina, Saskatchewan June, 1997 Copyright 1997: S.L. Rollings-Magnusson 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemîse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Romantic images of the opening of the 'last best west' bring forth visions of hearty pioneer men and women with children in hand gazing across bountiful fields of golden wheat that would make them wealthy in a land full of promise and freedom. The reality, of course, did not match the fantasy. -

Reception D Study

Reception d Study Harry Loewen University of Winnipeg For all the skills they have shown for centuries in the practical arts, Mennonites have failed to develop among themselves an appreciation for the literary arts and even less for literary artists.' This is not to say that Mennonites did not read books. As Jacob H. Janzen wrote with affection- ate irony some forty years ago: "They [Mennonites] liked to have good books. They bought Menno Simons' writings and laid them away to become dust covered on the corner ~helf."~Not only did Mennonites in Russia know the writings of Menno Simons; they also read other works written by non-Mennonites, even works of fiction, especially those which appealed to their sense of religious piety and practical concerns. Works like Jung-Stilling's Das Heimweh were not only appreciated by nineteenth-century Russian Mennonites, but were occasionally taken in a literal sense which could result in strange historical consequence^.^ During the nineteenth century Russian Mennonites did produce a few poets who achieved respect and popularity among the practically- minded Mennonites. The most outstanding among these was Bernhard Harder (1832-84) of the Molotschnaya who as preacher, teacher and poet spoke and sang his evangelical concerns into the hearts and minds of his people. Harder deserves his rightful place among the emerging Men- nonite writers, but as a poet he saw himself more in a didactic and moralizing role than as an artist. The Mennonite literary artist was unknown among the nineteenth-century Russian Mennonites.* It has been suggested that Mennonite literature not only grew out of the Russian-Mennonite tradition, but that in its appeal to Mennonite readers it was in part successful because there was a community which accepted this literature, however rel~ctantly.~This is no doubt true with regard to the kind of literature which was largely didactic and pietistic in Journal of Mennonite Studies Vol. -

Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra

View on Great Lavra Bell Tower and the Dormition Cathedral from the Far Caves Here in the 12th c. Nestor the Chronicler initiated the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra compilation of Rus’ cronicles, the outstanding physicians Agapit and Damian were curing people, Prince Sviatoslav The ensemble of heart-captivating beauty and harmo- (Nicola Sviatosha, the Pious) established the first hospital in ny opens up to you from the Dnipro – Pechersk Lavra, Rus’, while Alipiy founded the Lavra icon-painting school. which is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The first stone church the– Holy Dormition of Holy The Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra occupies a scenic amphitheater Theotokos Cathedral – was laid down on the Upper of the Dnipro hills, totaling an area of 24ha. Lavra area in 1073. In 1159 the monastery was awarded Its history starts in 1057, when monk Antoniy (Antho- the honourable title of Lavra (‘settlement’ in Greek). nius) returned from Athos with the blessing of the Holy In 1615 a printing house was established in the Lavra, Mount to found a monastery. Lavra Caves (hence the and the first book on Ukrainian history – ‘Sinopsys’ – was name of the monastery is derived from ‘pechera’, which published by Innokentiy Gizel in 1674. means ‘cave’ in Ancient Rus’) had been known since The Lavra complex totals 122 architectural monuments the 9th c., when the Varangians stayed there. The monas- as well as 8 surface and 6 underground churches. One can- tery started with an underground church in the Far Caves. not but mention in particular the Trinity Gateway Church When Anthonius left the monastery and dug a cave at the over the Holy Gate (1108) and the Church of Our Saviour bottom of the hill, which later became the beginning at Berestove (1113-1125), the latter one being famous for of the Near Caves, Feodosiy (Theodosius) was elected Fa- the 12th c. -

The Experience and Expression of Gender Among Halifax Women Taxi Drivers Since World War II Kimberly Berry

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:13 a.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine She's No Lady: The Experience and Expression of Gender among Halifax Women Taxi Drivers since World War II Kimberly Berry Volume 27, Number 1, October 1998 Article abstract "She's No Lady" explores the complex relationship between gender identity URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1016610ar and work culture as experienced by women taxi drivers in Halifax. Working in DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1016610ar a traditionally male industry, women taxi drivers often attract the attention of the press and the public as an amusing novelty or a scandalous disgrace. These See table of contents reactions are, in part, the result of the popular perception that masculine and feminine domain are mutually exclusive, restricted to men and women separately and respectively. Furthermore, characterized as highly competitive, Publisher(s) independent operators in a dangerous industry, taxi drivers embody a popular image of masculinity. While the place of women is generally considered to be Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine outside of masculine culture, women taxi drivers demonstrate the fluidity of gender cultures as they adeptly navigate the contested terrain of their ISSN masculine work-culture. Despite the routine comments and questions from passengers and colleagues alike, most women drivers find a considerable 0703-0428 (print) degree of membership within the larger community of drivers, and in this 1918-5138 (digital) sense become "one of the men"; seen first as taxi drivers and then women. Explore this journal Cite this article Berry, K. -

Preservings $10.00 No

-being the Magazine/Journal of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc. Preservings $10.00 No. 14, June, 1999 “A people who have not the pride to record their own history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.” — Jan Gleysteen Happy Birthday - Hanover Steinbach - 1874-1999 125 Years Old Congratulations to their day-to-day pursuits--the rat race, making tember 15, 1889, “15 years in America” with Hanover Steinbach on the more money or whatever. And yet, the celebra- worship services in Grünfeld. More typical an- occasion of its 125th birth- tion of anniversaries is one thing which inexora- niversary celebrations were held by the East Re- day, August 1, 1999, bly separates us from animals, defining a state of serve community in 1924, 1934, 1949, and more orginally founded as the civilization, and elevating homo sapiens as a no- recently, the centennial celebrations in 1974. The East Reserve in 1874. The bler race, showing that human beings, for all history of these celebrations and those involved first ship load of settlers their failings, cruelty and imperfections are still would in itself fill an issue of Preservings. arrived in Winnipeg (Fort capable of focusing their intelligence to matters The Hanover Steinbach Historical Society and Garry) on July 31, 1874, with beyond immediate needs and gratification, to ex- Preservings is proud to promote the activities of 10 Old Kolony (OK) and 55 Kleine plore the reasons for being, and, through a com- our 125th anniversary. -

Secular Mennonites and the Violence of Pacifism Miriam Toews at Mcmaster

Secular Mennonites and the Violence of Pacifism Miriam Toews at McMaster Maxwell Kennel Hamilton Arts and Letters 13.2 (Fall 2020). Special Issue edited by Grace Kehler. (https://samizdatpress.typepad.com/hal_magazine_thirteen-2/miriam-toews- violence-of-pacifism-by-maxwell-kennel-1.html) On February 25th of this violent year – just before the novel coronavirus and protests against police killings became definitive of 2020 – a far more peaceful event unfolded at McMaster University when Canadian author Miriam Toews spoke about her recent novel Women Talking in dialogue with three McMaster professors: event organizer, Grace Kehler (English & Cultural Studies), Petra Rethmann (Anthropology), and Travis Kroeker (Religious Studies).1 The council chambers in Gilmour Hall were filled with interested students, professors, and Hamiltonian literati who were eager to hear Toews read from Women Talking and respond to questions about the novel’s main motifs and tensions. 1 Both Kehler and Kroeker have published articles on Miriam Toews’ work. See: Grace Kehler, “Miriam Toews’s Parable of Infinite Becoming,” Vision 20.1 (2019), Grace Kehler, “Making Peace with Suicide: Reflections on Miriam Toews’s All My Puny Sorrows.” Conrad Grebel Review 35.3 (Fall, 2017), Grace Kehler, “Heeding the Wounded Storyteller: Toews’ A Complicated Kindness.” Journal of Mennonite Studies 34 (2016), Grace Kehler, “Representations of Melancholic Martyrdom in Canadian Mennonite Literature.” Journal of Mennonite Studies 29 (2011), and P. Travis Kroeker, “Scandalous Displacements: ‘Word’ and ‘Silent Light’ in Miriam Toews’ Irma Voth.” Journal of Mennonite Studies 36 (2018). 1 The room became very quiet when Toews began to read from page nineteen of Women Talking. -

German Culture. INSTITUTION Manitoba Univ., Winnipeg

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 282 074 CE 047 326 AUTHOR Harvey, Dexter; Cap, Orest TITLE Elderly Service Workers' Training Project. Block B: Cultural Gerontology. Module B.2: German Culture. INSTITUTION Manitoba Univ., Winnipeg. Faculty of Education. SPONS AGENCY Department of National Health and Welfare, Ottawa (Ontario). PUB DATE 87 GRANT 6553-2-45 NOTE 42p.; For related documents, see ED 273 809=819 and CE 047 321-333. AVAILABLE FROMFaculty of Education, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N2. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom use Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Aging (Individuals); Client Characteristics (Human Services); *Counselor Training; *Cross Cultural Training; *Cultural Background; *Cultural Context; Cultural Education; Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; German; Gerontology; Human Services; Immigrants; Interpersonal Competence; Learning Modules; Older Adults; Postsecondary Education IDENTIFIERS *German Canadians; *Manitoba ABSTRACT This learning module, which is part of a three-block Series intended to help human service workers develop the skills necessary to solve the problems encountered in their daily contact With elderly clients of different cultural backgrounds, deals with German culture. The first section provides background information about the German migrations to Canada and the German heritage. The module's general objectives are described next. The remaining Sections deal with German settlements in Manitoba, the bond between those who are able to understand and speak the German language, the role of religion and its importance in the lives of German-speaking Canadians, the value of family ties to German-speaking Canadians, customs common to German Canadians, and the relationship between the German-Canadian family and the neighborhood/community. -

"A Palace for the Public": Housing Reform and the 1946 Occupation of the Old Hotel Vancouver*

"A Palace for the Public": Housing Reform and the 1946 Occupation of the Old Hotel Vancouver* JILL WADE On 26 January 1946 thirty veterans led by a Canadian Legion sergeant- at-arms occupied the old Hotel Vancouver to protest against the acute housing problem in Vancouver. The incident climaxed two years of popular agitation over the city's increasingly serious accommodation shortages. In the end, this lengthy, militant campaign achieved some con crete housing reforms for Vancouver's tenants. The struggle and its results provide an excellent case study by which to examine the interaction between protest and housing reform in mid-twentieth century urban Canada. In the past, historians of Canadian housing have not concerned them selves with the interrelations of protest and reform. Rather, some have concentrated upon specific instances of improvements in housing: the activities of the Toronto Housing Company and the Toronto Public Housing Commission between 1900 and 1923; the distinctive urban land scape of homes and gardens in pre-1929 Vancouver; the establishment of the St. John's Housing Corporation in the forties; the reconstruction of Richmond following the 1917 Halifax explosion; and the array of federal programs undertaken between 1935 and 1971.1 Other historians have * I would like to thank Douglas Cruikshank, Robin Fisher, Logan Hovis and Allen Seager for their helpful comments during this paper's preparation. 1 Shirley Campbell Spragge, "The Provision of Workingmen's Housing: Attempts in Toronto, 1904-1920" (M.A. thesis, Queen's University, 1974); idem, "A Conflu ence of Interests: Housing Reform in Toronto, 1900-1920," in The Usable Urban Past: Planning and Politics in the Modern Canadian City, eds.