THE GEOGRAPHICAL IMPLICATIONS By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Mayfair 56 6 Parklands 173 8 Las Positas 213 Total Lease Up 442 12 Ventura Triangle 231 21 College Park 72 22 Portside Ventura Harbor 300 Total Under Construction 603 42 791 Camarillo Spring Senior Living 300 43 Barry Street Affordable Housing 60 44 Somis Ranch Development 360 45 University Glen Housing 480 46 Rio Urbana 167 47 Harvest at Limoneira 1,500 57 120 East Santa Clara 255 58 Willows at Ventura, The 306 Total Planned 3,428 103 Camino Ruiz 413 104 Channel Islands Center 953 105 Maulhardt 528 106 Paseos at Channel Islands Harbor, The 390 107 Victoria 116 108 211 East Thompson Blvd 50 109 Bluffs at Vista Del Mar, The 200 OXNARD SHORES 110 De Anza Courts 80 111 Northbank 70 112 Veterans Housing 122 137 Citrus II 78 138 Mar - Y - Cel 138 139 Seaward Avenue & Harbor Blvd 138 Total Prospective 3,276 1 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 3 Clarendon, The 335 7 Patricia Parc 65 Total Lease Up 400 41 2225-2239 Tapo Street 62 53 National Way Mixed-Use Village 190 54 Sycamore Landing 212 55 Essex Moorpark 200 56 299 Thousand Oaks Blvd 142 Total Planned 806 89 Agoura Village 107 90 3039 Cochran Street 50 91 Alamo & Tapo Street 278 92 Erringer & Heywood 62 93 Simi Valley Town Center Redevelopment 332 98 Hitch Ranch 494 99 500 Thousand Oaks 243 100 BLVD, The 98 101 Hodencamp Road & Thousand Oaks Blvd 240 102 Oaks, The 240 133 -

December 2017

DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS OVERSIGHT SUMMARY OF PENDING APPLICATIONS AS OF DECEMBER 2017 APPLICATION TYPE PAGE NO. BANK APPLICATION NEW BANK 1 MERGER 1 ACQUISITION OF CONTROL 1 SALE OF PARTIAL BUSINESS UNIT 2 NEW FACILITY 2 BRANCH RELOCATION 2 FACILITY RELOCATION 2 DISCONTINUANCE OF BRANCH OFFICE 4 DISCONTINUANCE OF FACILITY 4 PREMIUM FINANCE COMPANY APPLICATION NEW PREMIUM FINANCE COMPANY 5 ACQUISITION OF CONTROL 6 HEAD OFFICE RELOCATION 6 FOREIGN (OTHER NATION) BANK APPLICATION NEW OFFICE 6 OFFICE RELOCATION 7 FOREIGN (OTHER STATE) BANK APPLICATION NEW FACILITY 7 FACILITY RELOCATION 8 CREDIT UNION APPLICATION MERGER 8 MONEY TRANSMITTER APPLICATION NEW TRANSMITTER 9 ACQUISITION OF CONTROL 10 1 BANK APPLICATION NEW BANK Approved: 2 ENDEAVOR BANK 750 B Street, San Diego San Diego County Correspondent: Maryam Hamzeh Carpenter & Company 5 Park Plaza, Suite 950, Irvine, CA 92614 Filed: 8/12/16 Approved: 3/21/17 Application amended: 9/28/17: change of address from 401 West A Street, San Diego, San Diego County INFINITY BANK 6 Hutton Centre Drive, Santa Ana, Orange County Correspondent: Maryam Hamzeh Carpenter & Company 5 Park Plaza, Suite 950, Irvine, CA 92614 Filed: 7/7/16 Application amended: 12/21/16: change of name from SOCAL BANK (Proposed) Approved: 1/24/17 MERGER Approved: 1 ALBINA COMMUNITY BANK, Portland, Oregon, to merge with and into BENEFICIAL STATE BANK, Oakland, California Filed: 10/16/17 Approved: 11/29/17 ACQUISITION OF CONTROL Approved: 2 CARPENTER BANK PARTNERS, INC. and affiliates, to acquire control of PACIFIC PREMIER BANCORP -

Orange Line Transit Neighborhood Plans Community Workshop & Initial Concepts: Summary of Comments November and December 2017

ORANGE LINE TRANSIT NEIGHBORHOOD PLANS COMMUNITY WORKSHOP & INITIAL CONCEPTS: SUMMARY OF COMMENTS NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER 2017 Executive Summary The Orange Line Transit Neighborhood Plans (TNP) project aims to develop land use, zoning, and design regulations for the neighborhoods surrounding five Metro Orange Line stations in the south San Fernando Valley: North Hollywood, Van Nuys, Sepulveda, Reseda, and Sherman Way. The study area generally includes the corridors and some residential areas within a 15-minute walk or ½-mile radius of each station. During the first phase of the public planning process, in the first half of 2016, the Los Angeles Department of City Planning hosted four community workshops to identify opportunities to enhance neighborhoods surrounding transit stations, as well as several other small focus groups with specific stakeholder groups. Staff gathered input from the general public, including community residents, business owners, employees, transit users, and other participants about their thoughts, ideas, and concerns for the future of their neighborhood as it develops around transit, summarized here. Using the comments received through the first phase of outreach, in combination with station area context, existing City plans and policies, demographic analysis, and planning best practices, staff developed initial land use and zoning concepts for targeted changes in development rights and design regulations. These initial concepts were presented at two community workshops, on November 2, 2017 from 6-8:30 p.m.at the San Fernando Valley Arts & Cultural Center in Tarzana, and on November 15, 2017 from 6-8:30 p.m. at Van Nuys City Hall. Following these meetings, materials were made available online and staff solicited additional comments through the end of December. -

Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q19 107 124 92 43 91 93 42 ID PROPERTY UNITS 46 3 Las Positas 213 9 Coastal Village 101 56 Total Lease Up 314 94 42 Jefferson Vista Canyon 480 3 43 Sand Canyon Plaza 312 96 44 BLVD, The 98 45 University Glen Housing 480 45 44 46 Harvest at Limoneira 1,500 9 87 122 56 City Center 200 Total Planned 3,070 87 Agoura Village 107 91 Newhall Ranch: Entrada South 1,235 92 Newhall Ranch: Homestead South 2,918 93 Newhall Ranch: Potrero Valley 3,221 94 High Street 80 96 Camino Ruiz 413 107 Avanti South 325 122 West Village at Calabasas 180 124 Newhall Ranch: Entrada North 1,150 Total Prospective 9,629 5 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective a Berkshire Hathaway and Jefferies Financial Group company Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q19 103 8 126 104 101 102 106 58 47 105 127 ID PROPERTY UNITS 8 Parklands 173 10 Junction at Wagon Wheel, The 219 20 59 Total Lease Up 392 10 20 Portside Ventura Harbor 300 97 29 College Park 72 Total Under Construction 372 47 Ventura Triangle 231 98 58 120 East Santa Clara 255 59 Ventura Northbank 306 Total Planned 792 97 Channel Islands Center 953 100 98 Maulhardt 528 99 29 99 Paseos at Channel Islands Harbor, The 390 100 Victoria 116 101 211 East Thompson Blvd 50 102 Bluffs at Vista Del Mar, The 200 103 De Anza Courts 80 104 Mar - Y - Cel 138 105 Northbank 70 106 Veterans Housing 122 126 Citrus II 78 127 Seaward Avenue & Harbor Blvd 138 Total Prospective 2,863 1 mi Source: Yardi Matrix -

Dir-2018-4224-Db-Spp-1A

DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING APPEAL RECOMMENDATION REPORT City Planning Commission Case No.: DIR-2018-4224-DB-SPP-1A Date: October 24, 2019 CEQA No.: ENV-2018-4225-CE Time: After 8:30 am Council No.: 3 – Blumenfield Place: Van Nuys City Hall Plan Area: Encino-Tarzana Council Chambers, 2nd Floor 14410 Sylvan Street Specific Plan: Ventura/Cahuenga Boulevard Van Nuys, CA 91401 Corridor Certified NC: Tarzana Public Hearing: No GPLU: Community Commercial Zone: C2-1L Appeal Status: Not Further Appealable Applicant: Issac Mizrahi, Expiration Date: October 29, 2019 Etrog Properties, LLC Multiple Representative: Daniel Ahadian Approvals: Yes Nur-Development/Consulting Appellant: David Garfinkle, Tarzana Property Owners Association PROJECT 5431-5505 N. Reseda Boulevard LOCATION: PROPOSED The construction of a 5-story, 56-foot high, 40-unit apartment building with approximately PROJECT: 2,546 square feet of commercial floor area on the ground floor and two levels of subterranean parking, on an approximately 11,682 square-foot site (prior to dedication) in the C2-1L Zone. The project is located within the Ventura/Cahuenga Boulevard Corridor Specific Plan. The project proposes to set aside five units or 15 percent of the base dwelling units, for Very Low Income Households. APPEAL: An appeal of the August 1, 2019 Planning Determination which: 1. Determined that based on the whole of the administrative record, the Project is exempt from CEQA pursuant to State CEQA Guidelines, Section 15332, Class 32, and there is no substantial evidence demonstrating that an exception to a categorical exemption pursuant to CEQA Guidelines, Section 15300.2 applies; 2. Approved the construction of a new five-story, 56-foot high, mixed-use building with 2,546 commercial square feet on the ground floor and 40 residential units on the upper floors, reserving 5 units for Very Low Income household occupancy, for a period of 55 years and the following requested incentives: DIR-2018-4224-DB-SPP-1A Page 2 5431-5505 N. -

Medical and Dental Resource Guide 1

Medical and Dental Resource Guide Organization Contact Days & Hours of Services Additional Information SPA operation provided Palmdale Regional Medical (661) 382-5000 Admitting Hours Medical Sunday and after hours on any other day 1 Center Monday-Friday 6am-6pm patients can register in the Emergency 38600 Medical Center Drive Saturday 6am- 12pm Department. Palmdale, CA 93551 www.palmdaleregional.com High Desert Regional Health (661) 471-4000 Monday-Friday 8am-4:30pm Medical Patient must be part of a Medi-Cal 1 Center Appointment # Urgent Care Health plan through L.A. Care or 335 East Avenue I (661) 471-4400 7 days a week, 8am-11pm Health Net and be assigned to High Lancaster, CA 93535 Last patient is at 8pm Desert Regional Health Center as their medical home. Prefer patient makes an appointment before walk-ins. Antelope Valley Community (661) 942-2391 Monday-Friday 7:30am-5pm Medical Accepts Medicare, Medi-Cal, Medi-Cal 1 Clinic-Palmdale Dental Clinic & HMO, sliding scale, and other plans. 2151 East Palmdale Boulevard, Monday-Friday 7:30am-5pm Dental https://avclinic.org Palmdale, CA 93550 AVCC-Palmdale East (661) 942-2391 Monday-Friday 7:30am-5pm Medical Accepts Medicare, Medi-Cal, Medi-Cal 1 37926 47th Street East Saturday 8am-8pm HMO, sliding scale, and other plans. Palmdale, CA 93552 https://avclinic.org Antelope Valley Community (661) 942-2391 Monday-Friday 7:30am-5pm Medical Accepts Medicare, Medi-Cal, Medi-Cal 1 Clinic-Health & Wellness Dental Clinic & HMO, sliding scale, and other plans. 45104 10th Street West Monday-Friday 7:30am-5pm Dental Urgent Care is open 7 days a week Lancaster, CA 93534 from 7:30am-8pm https://avclinic.org Tarzana Treatment Centers (661) 723-4829 Tuesday-Saturday 8am-4pm Medical Accepts My Health LA, Medicare, 1 Antelope Valley- Family Medi-Cal, Private Insurance and Medical Clinic Sliding Scale. -

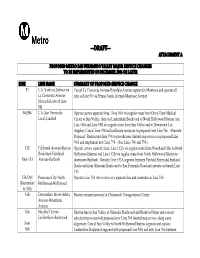

Draft--- Attachment A

---DRAFT--- ATTACHMENT A PROPOSED METRO SAN FERNANDO VALLEY MAJOR SERVICE CHANGES TO BE IMPLEMENTED IN DECEMBER 2006 OR LATER LINE LINE NAME SUMMARY OF PROPOSED SERVICE CHANGE 91 L.A.-Sunland-Sylmar via Cancel La Crescenta Avenue-Honolulu Avenue segment in Montrose and operate all La Crescenta Avenue trips as Line 90 via Pennsylvania Avenue-Montrose Avenue (Branch Route of Line 90) 94/394 L.A.-San Fernando Operate as two separate lines: Line 94A via regular route from Olive View Medical Local/Limited Center to Sun Valley, then via Lankershim Boulevard to North Hollywood Station (see Line 166) and Line 94B via regular route from Sun Valley and to Downtown Los Angeles; Cancel Line 394 and reallocate resources to proposed new Line 766. Alternate Proposal: Restructure Line 394 to provide new limited stop service on proposed Line 94A and implement new Line 794. (See Lines 766 and 794.) 152 Fallbrook Avenue-Roscoe Operate as two separate lines; Line 152A via regular route from Woodland Hills to North Boulevard-Vineland Hollywood Station and Line 152B via regular route from North Hollywood Station to New 153 Avenue-Burbank downtown Burbank. Reroute Line 152A segment between Tuxford Street and Sunland Boulevard from Glenoaks Boulevard to San Fernando Road and operate as branch Line 153. 156 Owl Panorama City-North Operate Line 156 owl service as a separate line and renumber as Line 356. (Renumber Hollywood-Hollywood to 356) 158 Devonshire Street-Arleta Shorten western terminal at Chatsworth Transportation Center. Avenue-Woodman Avenue 166 Nordhoff Street- Shorten line in Sun Valley at Glenoaks Boulevard and Branford Street and convert Lankershim Boulevard selected trips to provide proposed new Line 366 limited stop service along same New alignment; Cancel Sun Valley to North Hollywood Station segment and replace 366 Lankershim Boulevard segment with proposed Line 94A and new Line 766 between LINE LINE NAME SUMMARY OF PROPOSED SERVICE CHANGE Sylmar and North Hollywood Station or alternate proposal for new Line 394. -

Recommendations to Improve Pedestrian Safety on the Hoopa

RECOMMENDATIONS TO IMPROVE PEDESTRIAN SAFETY IN PACOIMA By Tony Dang, Jaime Fearer, Wendy Alfsen, Caro Jauregui, September 2015 California Walks; Jill Cooper, Katherine Chen, UC Berkeley SafeTREC Recommendations to Improve Pedestrian Safety in Pacoima BY TONY DANG, JAIME FEARER, WENDY ALFSEN, CARO JAUREGUI, CALIFORNIA WALKS; JILL COOPER, KATHERINE CHEN, UC BERKELEY SAFETREC INTRODUCTION The Pacoima neighborhood of the City of Los Angeles was identified as a focus community for a Community Pedestrian Safety Training, in collaboration with Pacoima Beautiful, based on residents’ interest in pedestrian safety and walkability, as well as recent and planned active transportation improvements in and around the neighborhood. Following additional conversations with the Active Transportation Division of the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT), Los Angeles Walks, Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), faculty from the Urban and Environmental Policy Institute at Occidental College, and the office of Councilmember Felipe Fuentes, the community invited the University of California at Berkeley’s Safe Transportation Research and Education Center (SafeTREC) and California Walks (Cal Walks) to Pacoima to facilitate a community-driven pedestrian safety action- planning workshop. Cal Walks facilitated the workshop on August 29, 2015, which consisted of: 1) an overview of multidisciplinary approaches to improve pedestrian safety; 2) two walkability assessments along Van Nuys Boulevard and other neighborhood streets; and 3) small group action planning discussions to facilitate the development of community-prioritized recommendations to inform the City’s ongoing active transportation efforts, as well as the County’s planning efforts for the East San Fernando Valley Transit Corridor project. This report summarizes the workshop proceedings, as well as ideas identified during the process and recommendations for pedestrian safety projects, policies, and programs. -

TOTAL $10,316,020,552 34,802 431 N La Cienega Los Angeles 90048 2600-2610 S

With Over 100 Years of Experience, Team Lustig-Bower has Handled Over $10 Billion in Multi-Family Land and Apartment Buildings in the Past 15 Years Alone EXISTING/ PROPERTY ADDRESS CITY PRICE PLANNED UNITS TOTAL $10,316,020,552 34,802 431 N La Cienega Los Angeles 90048 2600-2610 S. Roberston Boulevard Los Angeles 90034 $8,250,000 N/A 14320 Addison Street Sherman Oaks 91423 $19,200,000 56 8601 Glenoaks Boulevard (2020) Sun Valley 91352 $26,200,000 82 5350-5370 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles 90036 Confidential N/A 535 S. Kingsley Drive Los Angeles 90020 $34,600,000 72 514 N. Hayworth Avenue Los Angeles 90048 $3,995,000 10 11305 Santa Monica Boulevard Los Angeles 90025 Confidential N/A 464 E. Walnut Street Pasadena 91101 Confidential N/A 2511-2517 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles 90026 Confidential N/A 700 Locust Street Pasadena 91101 $19,350,000 69 21161 Victory Boulevard Canoga Park 91303 Confidential N/A 383 N. Main Street Pomona 91768 Confidential N/A 415, 441, 499 N. Garey Ave. & 109 W. Center St. Pomona 91768 Confidential 140 221 W. Holt Avenue Pomona 91768 Confidential 110 2707 & 2715 Pamoa Road Honolulu 96822 Confidential N/A 7441-7449 Sunset Blvd & 1502-1512 Gardner St Hollywood 90046 Confidential N/A 3731-3761 Stocker Street Los Angeles 90008 $35,000,000 N/A 6036 Variel Avenue Woodland Hills 91367 Confidential N/A 18427 Studebaker Road Cerritos 90703 $48,600,000 150 959 E. Stadium Way Los Angeles 90012 Confidential N/A 125-129 S. Linden Drive Beverly Hills 90212 Confidential N/A 9958-9964 Durant Drive Beverly Hills 90212 Confidential N/A 2033-2101 Virginia Avenue Santa Monica 90404 $13,700,000 40 2225 W. -

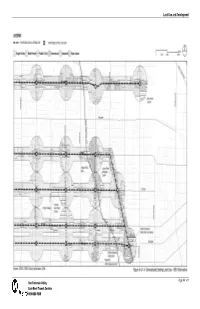

Land Use and Development

Land Use and Development Page 8-4.1-11 San Fernando Valley East-West Transit Corridor REVISED FEIR Land Use and Development Page 8-4.1-12 San Fernando Valley East-West Transit Corridor REVISED FEIR Land Use and Development Page 8-4.1-13 San Fernando Valley East-West Transit Corridor REVISED FEIR Land Use and Development This corridor consists of four RB stop locations with seven RB stops (See Figure 8-4.1-4). As discussed earlier, the North Hollywood Metro Red Line station area lies within a commercial district along Lankershim Boulevard. The Laurel Canyon Boulevard RB stops are located across from a healthcare office and two- to three-story apartment complexes. The surrounding area is comprised predominantly of single- and multi-family neighborhoods. The Coldwater Canyon Avenue stop area is characterized by single-family and some multi-family residential. Closest to the RB stops are single-family homes. Some commercial development exists along Coldwater Canyon Avenue, north of Magnolia Boulevard. The Woodman Avenue stop area consists exclusively of single-family homes. The Van Nuys Boulevard stop is located adjacent to a gas station and a grocery store. • Burbank Boulevard The Burbank Boulevard corridor extends from Lankershim Boulevard to Ventura Boulevard, after which it makes a loop along Ventura Boulevard and Reseda Boulevard in order to connect with the Ventura Rapid bus route. It consists of a total of seven potential RB stop locations with thirteen RB stops (See Figure 8-4.1-4 and Figure 8-4.1-5). East Valley For the most part, Burbank Boulevard from Lankershim Boulevard to I-405 consists of multi- family apartments along the street and single-family neighborhoods behind them. -

Crscommunity Resource Services

CRS Community Resource Services 8550 Balboa Boulevard, Suite 150 Northridge, CA 91325 (818) 739-5182 Phone (818) 739-5522 Fax Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services Directory www.childguidance.org Reviewed 09/2013 Page 1 The Child and Family Guidance Center is a LA County Department of Mental Health (DMH) contractor that provides Specialized Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) services to children, transition age youth, and adults utilizing evidence based treatment interventions (EBPs) that are consistent with LAC/DMH Mental Health services Act (MHSA). The Center also provides families with access to a comprehensive continuum of services depending on the needs of the family ranging from once a week; time limited mental services (PEI) to intensive in-home services that are delivered several times a week with 24-7 availability for crises. The Community Resource Services is a division dedicated to improve the quality of life for special needs children and their families by helping them to locate, access and effectively use essential community health and social services. Table of Contents Mental Health Centers Serving Children Accepting Medi-Cal 3 Counseling Centers for Adults, Teens and Children Not Accepting Medi-Cal 5 Mental Health Centers Serving Adults Accepting Medi-Cal 7 Substance Abuse Services for Youth and Adults 9 Mental Health Services for Transitional Youth 10 Mental Health Services for Children Age 0 to 5 Years 11 List of Pediatricians in the San Fernando Valley Accepting Medi-Cal 11 List of Psychiatrist in the San Fernando Valley Accepting Medi-Cal 12 The agencies on this document are listed for informational purposes only. -

Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20

Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20 43 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Coastline Ventura 231 2 Mayfair Townhomes 56 104 10 Portside Ventura Harbor 300 13 13 Parklands 173 55 54 Total Lease Up 760 105 106 134 103 56 1 42 Rio Urbana 147 43 Harvest at Limoneira 1,500 135 54 120 East Santa Clara 255 55 Citrus II 78 56 Northbank 50 10 57 97 57 The Willows at Ventura 306 Total Planned 2,336 2 42 95 Camino Ruiz 413 100 96 Country Club Village 250 95 97 Somis Ranch 360 98 University Glen Housing 480 101 99 Fisherman's Wharf at Channel 96 Islands Harbor 390 100 Fore RiverPark 333 101 Maulhardt 1,000 102 Victoria 116 102 103 211 East Thompson Blvd 50 104 De Anza Courts 80 99 105 Hawaiian Village Redevelopment 63 98 106 Veterans Housing 122 134 Mar - Y - Cel 138 135 Seaward Avenue & Harbor Blvd 97 Total Prospective 3,892 1 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Ventura County New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20 131 89 129 84 52 132 83 40 41 39 ID PROPERTY UNITS 9 Paxton Calabasas 78 Total Lease Up 78 39 The Landing at Arroyo 212 40 Tapo District Lofts 60 41 Vantage 54 52 Alamo & Tapo Street 278 53 299 Thousand Oaks Blvd 142 Total Planned 746 133 53 82 Agoura Town Center 63 92 90 83 3039 Cochran Street 50 91 84 Simi Valley Town Center Redevelopment 332 89 Hitch Ranch 494 94 90 500 Thousand Oaks 243 93 91 The BLVD 98 92 Hodencamp Road & Thousand Oaks Blvd 240 82 128 93 The Oaks 240 9 94 T.O.